Helminthic and Parasitic Infections

Community Health Nursing Perspectives

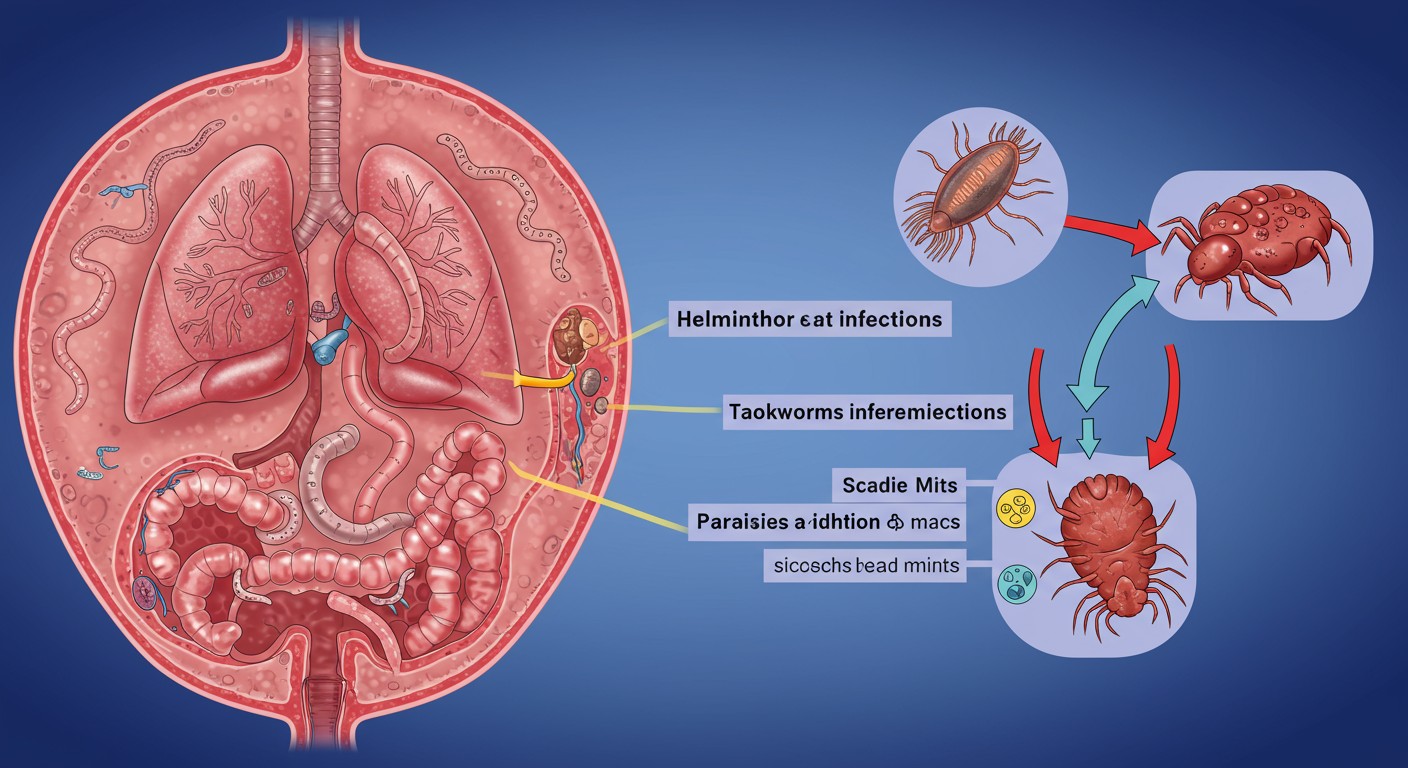

Illustration of common parasitic infections affecting humans

Table of Contents

Introduction to Parasitic Infections

Parasitic infections remain a significant global health concern, affecting millions of people worldwide, particularly in resource-limited settings. These infections are caused by organisms that live on or within a host organism and benefit at the expense of the host. From a community health nursing perspective, understanding parasitic infections is crucial for effective prevention, early detection, and management.

Parasitic infections can be broadly classified into:

Helminthic Infections

Caused by parasitic worms (helminths) that can be transmitted through:

- Soil-transmitted routes (e.g., roundworms, hookworms)

- Food-transmitted routes (e.g., tapeworms)

- Water-transmitted routes (e.g., schistosomiasis)

Ectoparasitic Infections

Caused by parasites that live on the surface of the host:

- Scabies (caused by the Sarcoptes scabiei mite)

- Pediculosis (lice infestation)

These parasitic infections contribute significantly to the global burden of disease, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions where they are endemic. Community health nurses play a pivotal role in controlling these parasitic infections through health education, prevention strategies, early detection, and appropriate management.

Key Point for Community Health Nurses

Parasitic infections often cluster in communities with poor sanitation, inadequate water supply, and limited healthcare access. Community-based interventions that address these social determinants of health are essential for sustainable control of parasitic infections.

Helminthic Infections

Epidemiology

Helminthic infections affect over 1.5 billion people globally, with soil-transmitted helminth (STH) infections being among the most common. These infections disproportionately affect impoverished communities where adequate sanitation is lacking.

| Helminth Type | Global Prevalence | Most Affected Regions | High-Risk Groups |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascaris lumbricoides (Roundworm) |

800-1200 million | Sub-Saharan Africa, Americas, China, East Asia | Children aged 5-15 years |

| Trichuris trichiura (Whipworm) |

600-800 million | Tropical and subtropical regions | Children in areas with poor sanitation |

| Hookworms (Ancylostoma, Necator) |

700-900 million | Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, South America | Agricultural workers, pregnant women |

| Taenia spp. (Tapeworms) |

50-60 million | Eastern Europe, Latin America, Asia | Consumers of undercooked pork/beef |

| Strongyloides stercoralis | 30-100 million | Tropical and subtropical regions | Immunocompromised individuals |

Risk factors for helminthic infections include:

- Poor sanitation and inadequate waste disposal

- Limited access to safe water

- Walking barefoot on contaminated soil

- Consumption of undercooked or raw meat

- Poor hand hygiene practices

- Overcrowded living conditions

Common Helminthic Infections

Soil-Transmitted Helminths

Ascariasis (Roundworm)

Causative Agent: Ascaris lumbricoides

Transmission: Ingestion of embryonated eggs from contaminated soil

Clinical Features: Often asymptomatic; heavy infections can cause abdominal pain, malnutrition, intestinal obstruction

Hookworm Infection

Causative Agent: Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator americanus

Transmission: Skin penetration by larvae in soil

Clinical Features: Iron-deficiency anemia, abdominal pain, protein loss

Trichuriasis (Whipworm)

Causative Agent: Trichuris trichiura

Transmission: Ingestion of embryonated eggs from contaminated soil

Clinical Features: Abdominal pain, diarrhea, rectal prolapse in severe cases

Food-Transmitted Helminths

Taeniasis (Tapeworm)

Causative Agent: Taenia saginata (beef), Taenia solium (pork)

Transmission: Consumption of undercooked meat containing larvae

Clinical Features: Often mild or asymptomatic; abdominal discomfort, weight loss, segments in stool

Trichinellosis

Causative Agent: Trichinella spiralis

Transmission: Consumption of undercooked meat containing encysted larvae

Clinical Features: Diarrhea, muscle pain, fever, periorbital edema

Diphyllobothriasis (Fish Tapeworm)

Causative Agent: Diphyllobothrium latum

Transmission: Consumption of raw or undercooked fish

Clinical Features: Vitamin B12 deficiency, abdominal discomfort

The life cycles of helminthic parasites typically involve:

- Egg release in feces or environment

- Development of eggs to infective stage in soil or intermediate host

- Transmission to humans through ingestion or skin penetration

- Migration and maturation within the human host

- Adult worms produce eggs, continuing the cycle

Prevention & Control Measures

Individual Level

- Regular handwashing with soap

- Wearing shoes outdoors

- Proper food preparation and cooking

- Avoiding swimming in contaminated water

- Consuming safe drinking water

Household Level

- Proper waste disposal

- Use of improved toilet facilities

- Water treatment at point of use

- Food safety practices

- Regular cleaning of living spaces

Community Level

- Mass drug administration programs

- Improved sanitation infrastructure

- Safe water supply systems

- Health education campaigns

- School-based deworming programs

WHO Recommended Control Strategy

The World Health Organization recommends a comprehensive approach to control soil-transmitted helminth infections through:

- Periodic deworming of at-risk populations (pre-school and school-age children, women of childbearing age)

- Health education to reduce transmission and reinfection

- Improved sanitation to reduce soil contamination with infective eggs

Screening & Diagnosis

Early detection of helminthic infections is crucial for effective management and prevention of complications. Community health nurses should be familiar with screening approaches and diagnostic methods.

| Diagnostic Method | Procedure | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Microscopy | Examination of stool samples for eggs, larvae, or adult worms | Simple, inexpensive, widely available | Low sensitivity for light infections, requires trained personnel |

| Kato-Katz Technique | Quantitative stool examination | Standardized, assesses intensity of infection | Time-consuming, multiple samples needed |

| Concentration Techniques | Sedimentation or flotation methods to concentrate eggs | Improved sensitivity | More complex than direct microscopy |

| Serology/Immunodiagnostics | Detection of antibodies or antigens in blood | High sensitivity, useful for specific infections | Cross-reactivity, may not distinguish current from past infection |

| Molecular Techniques (PCR) | Detection of parasite DNA in stool samples | High sensitivity and specificity | Expensive, requires specialized equipment |

Community-based screening approaches:

- Targeted screening of high-risk groups (school children, pregnant women)

- Integration with school health programs

- Community-wide screening during mass drug administration campaigns

- Case finding during routine healthcare visits

Management, Referral, and Follow-up

Primary Management

Anthelmintic medications are the cornerstone of treatment for helminthic infections. Common drugs include:

| Medication | Target Parasites | Dosing | Precautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albendazole | Roundworms, hookworms, whipworms | 400mg single dose (adults); 200mg for children 12-24 months | Contraindicated in first trimester of pregnancy |

| Mebendazole | Roundworms, hookworms, whipworms | 100mg twice daily for 3 days or 500mg as single dose | Not recommended during pregnancy |

| Ivermectin | Strongyloidiasis, also effective for scabies | 200μg/kg as single dose | Not for children <15kg or pregnant women |

| Praziquantel | Tapeworms, flukes | 5-10mg/kg as single dose for tapeworms | Take with food; may cause dizziness |

| Pyrantel Pamoate | Roundworms, pinworms, hookworms | 11mg/kg (max 1g) as single dose | Use with caution in liver disease |

Supportive Care

- Nutritional support for malnourished patients

- Iron supplementation for hookworm-related anemia

- Fluid and electrolyte replacement for diarrheal symptoms

- Pain management for abdominal discomfort

Referral Criteria

Community health nurses should refer patients with the following:

- Severe anemia (hemoglobin <7 g/dL)

- Signs of intestinal obstruction (severe abdominal pain, vomiting, distension)

- Neurological symptoms (suggesting neurocysticercosis)

- Recurrent infections despite adequate treatment

- Immunocompromised patients with helminthic infections

- Pregnant women requiring treatment

Follow-up Care

Follow-up is essential to ensure treatment effectiveness and prevent reinfection:

- Stool examination 2-4 weeks after treatment completion

- Hemoglobin monitoring for patients with hookworm infection

- Reinforce preventive measures to avoid reinfection

- Family screening and treatment for household contacts

- Regular follow-up for high-risk individuals (immunocompromised, chronic malnutrition)

Warning Signs Requiring Immediate Action

- Severe abdominal pain, distension, or vomiting

- Seizures or altered mental status

- Respiratory distress

- Severe dehydration or electrolyte imbalances

- Signs of peritonitis or intestinal perforation

Scabies

Epidemiology

Scabies is a common parasitic infection affecting approximately 200 million people worldwide at any time. It is caused by the microscopic mite Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis, which burrows into the skin and lays eggs, triggering a hypersensitivity reaction.

Distribution & Burden

- Global distribution with higher prevalence in tropical regions

- Affects all socioeconomic groups but more common in resource-limited settings

- Endemic in many developing countries with prevalence rates of 5-10%

- Institutional outbreaks common in nursing homes, childcare facilities, prisons

- Seasonal patterns with higher rates in winter in temperate climates

Transmission & Risk Factors

- Direct, prolonged skin-to-skin contact (15-20 minutes)

- Shared bedding, clothing, or towels (less common)

- Overcrowded living conditions

- Poverty and limited access to water for hygiene

- Immunosuppression (risk for crusted/Norwegian scabies)

- Delayed diagnosis leading to ongoing transmission

Community health nurses should be aware that scabies has significant public health implications beyond the initial infestation:

- Secondary bacterial infections (impetigo, cellulitis, abscesses)

- Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis following streptococcal superinfection

- Rheumatic fever risk in endemic areas

- Psychological impact (stigma, sleep disturbance, social isolation)

Clinical Features

Classic Scabies

Symptoms:

- Intense pruritus, especially at night

- Pruritus often precedes visible skin lesions

- Family members often similarly affected

Skin Manifestations:

- Burrows: thread-like, grayish, tortuous tracks (pathognomonic)

- Papules, vesicles, excoriations

- Secondary eczematization from scratching

Distribution:

- Interdigital web spaces

- Flexor surfaces of wrists

- Axillae and periumbilical region

- Genitalia in males

- Periareolar region in females

- Buttocks and lower extremities

Crusted (Norwegian) Scabies

A severe form occurring in immunocompromised individuals, the elderly, and those with neurological disorders. Characterized by:

- Hyperkeratotic, crusted lesions containing thousands of mites

- Minimal or absent pruritus in some cases

- Widespread distribution including face, scalp, and back

- Highly contagious due to mite burden

- Associated with high mortality if untreated

Special Considerations

Scabies in infants and young children presents differently:

- Can involve the head, face, neck, palms, and soles

- May present as vesicles, pustules, or nodules

- Persistent nodules may remain for weeks after treatment

Diagnosis

Community health nurses should be familiar with diagnostic approaches for scabies:

| Diagnostic Method | Procedure | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Diagnosis | Based on characteristic distribution and symptoms | Most common approach in community settings; requires experience |

| Microscopic Examination (Skin Scraping) | Scraping of burrows or papules, examination under microscope for mites, eggs, or feces | Definitive diagnosis; low sensitivity (50%) and requires equipment |

| Dermatoscopy | Visualization of burrows using handheld dermatoscope | Non-invasive; improves diagnostic accuracy; equipment may not be available |

| Ink Test/Burrow Ink Test | Application of ink to suspected areas, then wiping away excess; ink penetrates burrows | Simple field technique; limited sensitivity |

Prevention & Control Measures

Individual Level

- Early diagnosis and treatment

- Avoiding close contact with infected individuals

- Proper personal hygiene

- Using hot water for washing bedding and clothing

- Isolating personal items during treatment

Household Level

- Simultaneous treatment of all household members

- Environmental decontamination

- Laundering all bedding and clothing at 60°C

- Sealing non-washable items in plastic bags for 72 hours

- Educational intervention for families

Community Level

- Mass drug administration in endemic areas

- Health education campaigns

- Improved housing conditions

- Integrated approach with other skin NTDs

- Institutional outbreak management protocols

Key Control Strategies for Community Health Nurses

- Case finding through community outreach

- Contact tracing and simultaneous treatment

- Integration of scabies control with other public health programs

- School-based screening programs

- Training of community health workers for early recognition

Management, Referral, and Follow-up

Primary Management

Treatment involves both anti-scabicidal agents and measures to prevent reinfestation:

| Medication | Application | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permethrin 5% cream | Apply from neck down, leave for 8-14 hours, then wash off. Repeat after 7 days. | First-line treatment, safe in pregnancy and for children >2 months | Cost, potential resistance |

| Ivermectin (oral) | 200μg/kg as single dose, repeat after 7-14 days | Convenient, effective for mass treatment, good for crusted scabies | Not approved for scabies in all countries, contraindicated in pregnancy |

| Benzyl benzoate 10-25% | Apply for 24 hours, then wash off. Repeat for 3 days, then again after 7 days. | Inexpensive, widely available | Skin irritation, unpleasant odor, complex regimen |

| Sulfur 5-10% in petrolatum | Apply for 3 consecutive nights | Safe in pregnancy and infants, inexpensive | Messy, unpleasant odor, can stain clothing |

Supportive Care

- Antihistamines for pruritus (may continue for 2-4 weeks after treatment)

- Topical steroids for eczematous reactions

- Antibiotics for secondary bacterial infections

- Emollients for dry skin and to repair skin barrier

Environmental Measures

- Machine wash all clothing, bedding, and towels at 60°C and dry in hot dryer

- Items that cannot be washed should be sealed in plastic bags for at least 72 hours

- Vacuum furniture and carpets (though environmental decontamination is secondary to treating the person)

Important Considerations

- All household members and close contacts should be treated simultaneously, even if asymptomatic

- Symptoms may persist for 2-4 weeks after successful treatment (post-scabetic itch)

- Treatment failure is often due to incorrect application, reinfection from untreated contacts, or resistance

Referral Criteria

Community health nurses should refer patients with:

- Suspected crusted (Norwegian) scabies

- Severe secondary bacterial infections requiring systemic antibiotics

- Treatment failure after two complete courses

- Immunocompromised patients

- Infants under 2 months of age

- Pregnant women requiring treatment other than permethrin

Follow-up Care

- Follow-up evaluation 2 weeks after treatment

- Assessment for treatment failure or reinfestation

- Monitoring for secondary complications

- Reinforce preventive measures

- Community-level follow-up for institutional outbreaks

Pediculosis

Epidemiology

Pediculosis refers to infestation with lice, which are obligate ectoparasites that feed on human blood. There are three types of lice that infest humans:

Pediculosis Capitis

Agent: Pediculus humanus capitis (head louse)

Global Burden: 6-12 million cases annually in the U.S. alone; affects primarily school-aged children

Transmission: Direct head-to-head contact; sharing of combs, hats, or headgear

Risk Factors:

- School-aged children (5-11 years)

- Female gender

- Close living conditions

- Long hair

Pediculosis Corporis

Agent: Pediculus humanus corporis (body louse)

Global Burden: Common in homeless populations, refugee camps, and disaster-affected areas

Transmission: Contact with infested clothing or bedding

Risk Factors:

- Homelessness

- Poor hygiene

- Crowded living conditions

- Limited access to laundry facilities

Note: Can transmit diseases such as epidemic typhus, trench fever, and relapsing fever

Pediculosis Pubis

Agent: Pthirus pubis (pubic louse or “crab louse”)

Global Burden: Estimated 3-4 million cases annually worldwide

Transmission: Sexual contact; occasionally through shared towels or bedding

Risk Factors:

- Multiple sexual partners

- History of other STIs

- Shared beds or bedding

- Young adults (15-25 years)

Life Cycle of Lice:

- Eggs (Nits): Cemented to hair shafts (head lice), clothing seams (body lice), or pubic hair. Hatch in 7-10 days.

- Nymphs: Immature lice that molt three times before becoming adults (takes about 7 days).

- Adults: Feed on blood multiple times daily. Female lays 3-8 eggs per day. Live for about 30 days.

Public Health Significance

- Head lice cause significant school absenteeism

- Body lice can transmit serious diseases in outbreak settings

- Social stigma and psychological distress associated with infestations

- Economic burden from treatment costs and lost workdays for caregivers

- Growing resistance to pediculicides is a concern

Clinical Features

Head Lice

Symptoms:

- Intense itching of the scalp

- Tickling sensation of something moving in the hair

- Irritability and difficulty sleeping

Signs:

- Nits attached to hair shafts, particularly behind ears and at nape of neck

- Adult lice on scalp (difficult to spot as they move quickly)

- Excoriation marks from scratching

- Cervical lymphadenopathy

Body Lice

Symptoms:

- Intense pruritus, especially at night

- Discomfort from bites

- Sleep disturbance

Signs:

- Bite marks and excoriations primarily on shoulders, trunk, and buttocks

- Erythematous macules and papules at bite sites

- Secondary bacterial infection

- Nits and lice found in seams of clothing (not on body)

- “Vagabond’s disease” – hyperpigmentation and thickening of skin in chronic cases

Pubic Lice

Symptoms:

- Intense itching in pubic region

- Irritation from bites

- Blue/gray macules (maculae ceruleae) from louse saliva

Signs:

- Crab-like lice and nits attached to pubic hair

- May also infest eyebrows, eyelashes, axillary hair, and beard

- Excoriations from scratching

- Secondary bacterial infection

Diagnosis

Community health nurses should be familiar with diagnostic approaches for pediculosis:

| Lice Type | Diagnostic Method | Procedure |

|---|---|---|

| Head Lice | Visual Inspection | Systematic examination of scalp and hair for live lice and nits, particularly behind ears and at nape of neck |

| Wet Combing | Combing wet hair with fine-toothed comb onto white paper or cloth to detect lice | |

| Dermoscopy | Use of dermatoscope to visualize lice and differentiate nits from hair casts or dandruff | |

| Body Lice | Clothing Examination | Inspection of seams of clothing (especially waistbands, inner seams) for lice and nits |

| Pubic Lice | Visual Inspection | Examination of pubic hair and other body hair for crab-like lice and nits; check for maculae ceruleae |

Important Diagnostic Considerations

- Presence of live lice confirms active infestation

- Nits close to scalp (<6mm) suggest active or recent infestation

- Nits farther from scalp suggest past infestation

- Dandruff and hair casts can be mistaken for nits but are easily removed unlike firmly attached nits

- Pubic lice infestations may coexist with other STIs, so screening may be warranted

Prevention & Control Measures

Head Lice Prevention

- Avoid head-to-head contact during play and activities

- Don’t share personal items (combs, brushes, hats, scarves)

- Keep personal items separate at school, sports facilities

- Regular screening of school-aged children

- Educate children about transmission

Body Lice Prevention

- Regular bathing with soap and water

- Regular laundering of clothing and bedding

- Access to clean clothing and bedding

- Adequate hygiene facilities for vulnerable populations

- Proper laundering facilities in shelters, camps

Pubic Lice Prevention

- Safe sexual practices

- Avoiding sharing towels and bedding

- Treatment of sexual partners

- STI screening when pubic lice identified

- Education about transmission

Community-Level Control Strategies

- School-based education and screening programs for head lice

- Outreach programs for homeless populations for body lice prevention

- Integration of lice screening with other health services

- No-nit policies are NOT recommended by public health authorities as they can lead to unnecessary school exclusion

- Surveillance systems to monitor pediculicide resistance

Myth Dispelling for Community Education

- Head lice do not jump or fly; they crawl

- Head lice infestation is not related to cleanliness or socioeconomic status

- Pets do not spread human lice

- Head lice prefer clean hair to dirty hair

- Head lice live less than 24 hours when off a human host

Management, Referral, and Follow-up

Treatment Approaches

| Treatment Category | Medications/Methods | Application/Usage | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pediculicides (Chemical) | Permethrin 1% (OTC) | Apply to hair/affected area, leave for 10 minutes, rinse. Repeat in 7-10 days. | First-line for head lice; safe for children >2 months; growing resistance |

| Pyrethrin with piperonyl butoxide (OTC) | Apply to dry hair, leave for 10 minutes, rinse. Repeat in 7-10 days. | Not for pyrethrin allergies or ragweed allergy; growing resistance | |

| Malathion 0.5% (Prescription) | Apply to dry hair, leave for 8-12 hours, rinse. May repeat after 7-9 days if needed. | Only for age >6 years; flammable; not first-line | |

| Ivermectin (Prescription, oral or topical) | Oral: 200μg/kg as single dose, repeat in 7-10 days

Topical: Apply to dry hair, leave for 10 minutes, rinse |

For resistant cases; oral not for children <15kg; topical for age >6 months | |

| Mechanical Removal | Wet combing | Wet hair, apply conditioner, use fine-toothed comb to remove lice/nits. Repeat every 3-4 days for 2 weeks. | Time-consuming but effective; good option for pregnant/nursing women and young children |

| Electric lice combs | Use on dry hair to electrocute lice | Adjunct to other treatments; not for wet hair; requires multiple sessions | |

| Suffocation/Desiccation | Dimethicone | Apply to dry hair, leave for 8 hours, shampoo out. Repeat in 7 days. | Non-toxic; works by physical action; less resistance concern |

| Benzyl alcohol 5% | Apply to dry hair, leave for 10 minutes, rinse. Repeat in 7 days. | For children >6 months; not ovicidal so second treatment essential |

Specific Management by Lice Type

Head Lice Management

Treatment:

- Pediculicides as detailed in table

- Wet combing as adjunct or alternative

- Treat all household members with active infestation simultaneously

Environmental Measures:

- Wash items that have been in contact with head in hot water (>50°C)

- Dry items in hot dryer for 20 minutes

- Seal non-washable items in plastic bags for 2 weeks

- Vacuum furniture, carpets, car seats

- Soak combs/brushes in hot water (>54°C) for 5-10 minutes

Body Lice Management

Treatment:

- Improving personal hygiene (regular bathing)

- Topical pediculicides rarely needed if clothing/bedding addressed

- Treatment of secondary bacterial infections if present

Environmental Measures:

- Laundering all clothing and bedding in hot water

- Regular changing of clothes

- Providing clean clothing to homeless/displaced persons

- Institutional decontamination in shelters/camps

Pubic Lice Management

Treatment:

- Pediculicides (permethrin, pyrethrin)

- Special management for eyelash infestation (petroleum jelly applied with cotton)

- Treatment of all sexual partners from previous 30 days

Additional Measures:

- STI screening (pubic lice can be marker for other STIs)

- Washing of bedding and towels

- Abstinence from sexual contact until treatment complete

- Education about prevention of recurrence

Referral Criteria

Community health nurses should refer patients with:

- Treatment failure after two complete courses

- Severe secondary bacterial infections

- Eyelash involvement requiring specialized treatment

- Body lice with signs of systemic illness (possible vector-borne disease)

- Extensive excoriation or impetigo requiring systemic antibiotics

- Uncertainty in diagnosis

Follow-up Care

- Reexamination 7-10 days after treatment

- Assessment for treatment failure or reinfestation

- Evaluation of household members or sexual contacts

- Monitoring for secondary complications

- Education about prevention of recurrence

Treatment Challenges

- Increasing resistance to permethrin and pyrethrin

- Poor compliance with treatment protocols

- Difficulty treating all contacts simultaneously

- Overtreatment and unnecessary environmental measures

- Stigma preventing timely care-seeking

Community Health Nursing Interventions

Community health nurses play a pivotal role in the prevention, control, and management of parasitic infections. Their interventions span individual, family, and community levels, focusing on both treatment and prevention of parasitic infections.

Assessment & Surveillance

- Conducting community assessment to identify high-risk areas

- Screening vulnerable populations (school children, homeless individuals)

- Monitoring disease trends and outbreak detection

- Reporting notifiable parasitic infections to health authorities

- Evaluating effectiveness of intervention programs

- Conducting household surveys for parasitic infections

Health Education & Promotion

- Developing culturally appropriate educational materials

- Conducting school-based education on prevention

- Teaching proper handwashing techniques

- Educating about safe food preparation and storage

- Promoting environmental sanitation

- Conducting community workshops on parasite prevention

- Addressing myths and misconceptions about parasitic infections

Treatment & Case Management

- Implementing mass drug administration programs

- Providing treatment according to current guidelines

- Ensuring medication compliance and proper administration

- Managing side effects of anti-parasitic medications

- Contact tracing and treatment of household members

- Conducting home visits for complicated cases

- Coordinating care with other healthcare providers

Community Mobilization & Advocacy

- Engaging community leaders in parasitic infection control

- Advocating for improved sanitation infrastructure

- Mobilizing community resources for prevention

- Partnering with schools, workplaces, and community organizations

- Supporting policy development for parasitic disease control

- Advocating for access to medications for vulnerable populations

- Promoting integration of parasite control with other health programs

The Nursing Process in Parasitic Infection Control

Assessment

- Identify risk factors in individuals and communities

- Assess for signs and symptoms of parasitic infections

- Evaluate environmental conditions contributing to transmission

Diagnosis

- Formulate nursing diagnoses related to parasitic infections

- Identify community-level health needs

- Determine priorities for intervention

Planning

- Develop comprehensive care plans for infected individuals

- Create community-level intervention strategies

- Establish measurable goals and outcomes

Implementation

- Execute treatment and prevention strategies

- Coordinate with multidisciplinary teams

- Conduct educational interventions

Evaluation

- Assess effectiveness of interventions at individual and community levels

- Monitor for treatment success, complications, or recurrence

- Modify approaches based on outcomes and emerging evidence

- Document and share successful strategies

Mnemonics & Learning Aids

WORMS: Helminth Prevention Strategy

- Wash hands thoroughly before eating and after using toilet

- Opt for properly cooked food and treated water

- Regular deworming for at-risk populations

- Manage waste and improve sanitation

- Shoes should be worn to prevent soil contact

SCRATCH: Key Signs of Scabies

- Severe itching, worse at night

- Curved burrows in skin

- Rash with papules and vesicles

- Affected household contacts

- Typical distribution (wrists, finger webs, genitals)

- Chronic without treatment

- Hypersensitivity to mite proteins

LICE: Managing Pediculosis

- Look for lice and nits systematically

- Implement appropriate treatment

- Contact tracing and simultaneous treatment

- Environmental measures and education

PARASITE: Community Nursing Approach

- Prevent transmission through education

- Assess individual and community risk factors

- Recognize signs and symptoms early

- Apply appropriate treatment protocols

- Screen high-risk populations

- Implement environmental interventions

- Track outcomes and adjust strategies

- Empower communities for sustainable control

Differential Diagnosis Aid

Common skin conditions that may be confused with parasitic infections:

| Condition | Distinguished From | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|---|

| Eczema | Scabies | No burrows; distribution pattern different; no household clustering |

| Folliculitis | Pediculosis | Centered around hair follicles; no visible lice or nits |

| Seborrheic Dermatitis | Head Lice | Greasy scales; no nits attached to hair shafts |

| Contact Dermatitis | Scabies/Pediculosis | History of exposure to irritant; distribution related to contact |

| Papular Urticaria | Scabies | History of insect bites; no burrows; different distribution |

Global Best Practices

WHO Preventive Chemotherapy

The World Health Organization recommends mass drug administration (MDA) as a cost-effective strategy for controlling soil-transmitted helminth infections in endemic areas.

Key Elements:

- Regular deworming of at-risk populations (preschool and school-age children, women of childbearing age)

- Integration with other neglected tropical disease programs

- School-based deworming programs

- Monitoring for drug resistance

Success Story: Kenya’s National School-Based Deworming Program has treated over 6 million children annually since 2012, reducing STH prevalence and improving school attendance.

Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS)

CLTS is an innovative approach that empowers communities to eliminate open defecation and improve sanitation, directly impacting soil-transmitted helminth transmission.

Key Elements:

- Community triggering sessions to raise awareness about fecal-oral transmission

- Engaging community leaders and influencers

- Community-driven solutions rather than external subsidies

- Open Defecation Free (ODF) certification as a milestone

Success Story: Bangladesh has implemented CLTS in over 40,000 villages, with many achieving ODF status and significant reductions in parasitic diseases.

One Health Approach for Parasitic Control

One Health recognizes the interconnection between human, animal, and environmental health in addressing parasitic infections, particularly zoonotic helminthiases.

Key Elements:

- Multisectoral collaboration (public health, veterinary services, environmental agencies)

- Integrated surveillance systems

- Joint interventions targeting human and animal reservoirs

- Environmental management to break transmission cycles

Success Story: China’s comprehensive control program for schistosomiasis has dramatically reduced prevalence through integrated human treatment, snail control, and animal reservoir management.

Integrated Skin NTD Management

WHO’s integrated approach to skin Neglected Tropical Diseases combines surveillance and management of scabies with other skin conditions.

Key Elements:

- Training healthcare workers to recognize multiple skin NTDs

- Integrated case management and reporting

- Mass drug administration for multiple skin NTDs when appropriate

- Stigma reduction strategies

Success Story: The Pacific Island Countries have implemented successful MDA programs for scabies, dramatically reducing prevalence from over 30% to less than 2% in some communities using ivermectin.

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) Interventions

WASH interventions are fundamental to sustainable parasitic infection control, addressing root causes rather than just treating symptoms.

Water

- Improved access to clean water sources

- Household water treatment technologies

- Protected water storage practices

Sanitation

- Construction and use of improved latrines

- Safe disposal of infant feces

- Wastewater management systems

Hygiene

- Handwashing promotion and facilities

- Food hygiene education

- Environmental cleanliness

Success Story: The Integration of WASH interventions with deworming in Ethiopian schools led to a sustained 90% reduction in STH infections, compared to 50% reduction with deworming alone.

References

- World Health Organization. (2023). Soil-transmitted helminth infections. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/soil-transmitted-helminth-infections

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Parasites – Soil-transmitted helminths. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/sth/index.html

- World Health Organization. (2023). Scabies. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/scabies

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Parasites – Lice. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/index.html

- Gyorkos, T. W., & Maheu-Giroux, M. (2018). Effectiveness of deworming programs at deworming children aged 1–14 years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 6(12), e1363-e1374.

- Engelman, D., Cantey, P. T., Marks, M., Solomon, A. W., Chang, A. Y., Chosidow, O., … & Steer, A. C. (2019). The public health control of scabies: priorities for research and action. The Lancet, 394(10192), 81-92.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) for the prevention and care of NTDs: A manual for WASH implementers. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022782

- Feldmeier, H., & Heukelbach, J. (2009). Epidermal parasitic skin diseases: a neglected category of poverty-associated plagues. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 87, 152-159.

- Romani, L., Whitfeld, M. J., Koroivueta, J., Kama, M., Wand, H., Tikoduadua, L., … & Steer, A. C. (2015). Mass drug administration for scabies control in a population with endemic disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 373(24), 2305-2313.

- Brooker, S., Kabatereine, N. B., Fleming, F., & Devlin, N. (2008). Cost and cost-effectiveness of nationwide school-based helminth control in Uganda: intra-country variation and effects of scaling-up. Health Policy and Planning, 23(1), 24-35.

- Burkhart, C. G., & Burkhart, C. N. (2006). Scabies: an epidemiologic reassessment. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1078(1), 358-363.

- Sangare, A. K., Doumbo, O. K., & Raoult, D. (2016). Management and treatment of human lice. BioMed Research International, 2016, 8962685.