Special Obstetric Populations

Adolescent Pregnancy, Elderly Primigravida, and Grand Multiparity

Comprehensive Nursing Education Resource

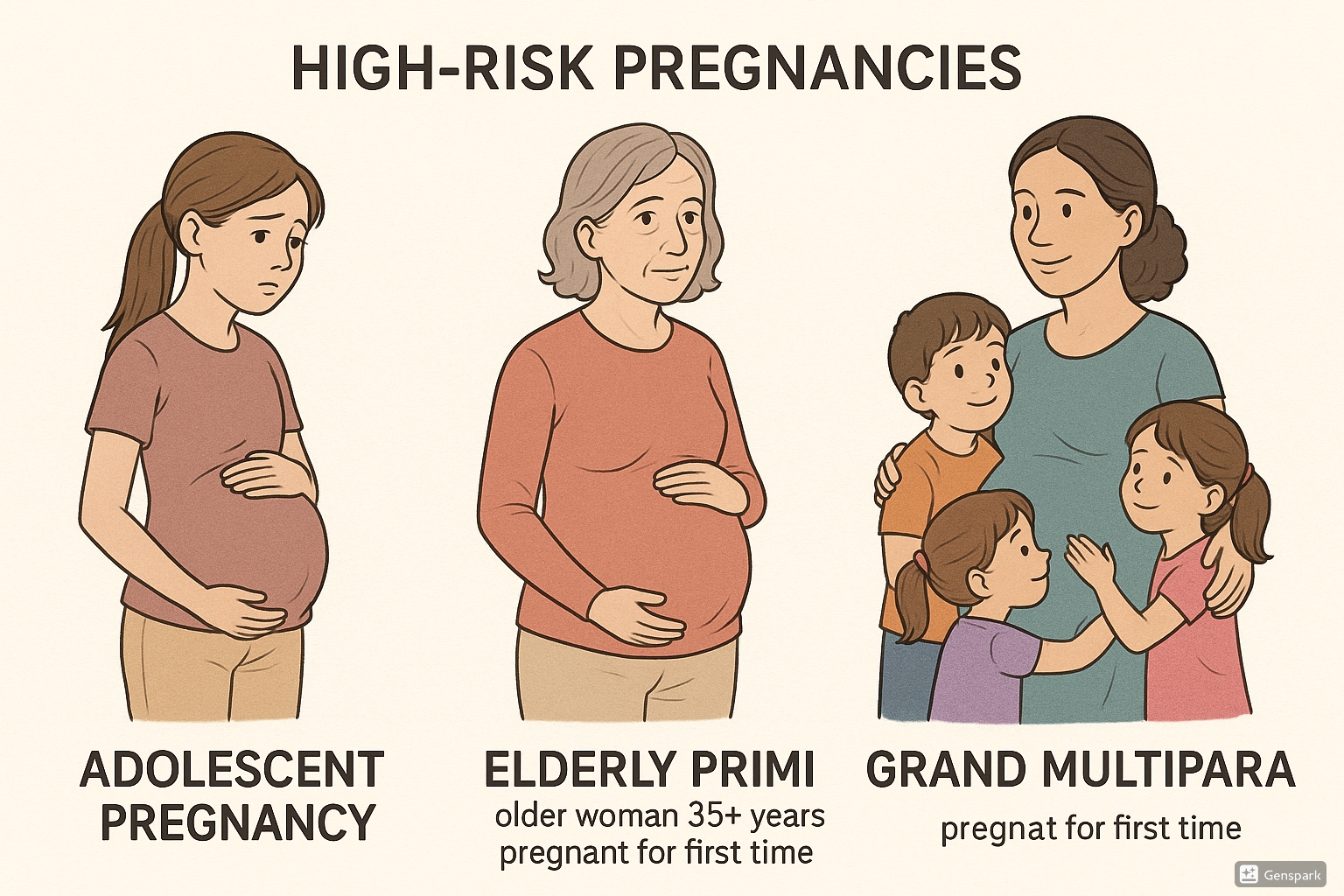

Medical illustration depicting three high-risk pregnancy categories: adolescent pregnancy (left), elderly primigravida (center), and grand multiparity (right)

Table of Contents

Introduction to High-Risk Pregnancy

The field of obstetric nursing requires specialized knowledge of various high-risk pregnancy categories. This comprehensive guide focuses on three significant high-risk populations: adolescent pregnancy, elderly primigravida, and grand multiparity. Each category presents unique physiological, psychological, and social challenges that demand tailored nursing interventions.

A high-risk pregnancy refers to a pregnancy in which there is an increased likelihood of complications that could affect the mother, the fetus, or both. These complications may arise due to various factors including maternal age, parity, pre-existing medical conditions, or pregnancy-related complications. Early identification, continuous monitoring, and appropriate interventions are crucial for optimizing outcomes in these populations.

Why understanding these special populations matters: The classification of pregnancies based on age and parity helps healthcare professionals anticipate potential complications, implement preventive measures, and develop appropriate management plans. This classification guides risk assessment, resource allocation, and decision-making throughout the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum periods.

Nurses play a pivotal role in the care of these high-risk pregnancy populations. They serve as advocates, educators, care coordinators, and direct care providers. Their ability to recognize early warning signs, implement evidence-based interventions, and provide compassionate care significantly influences maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Worldwide Statistics: According to the World Health Organization, approximately 12 million girls aged 15-19 give birth each year in developing regions; advanced maternal age pregnancies have increased by 20% in the last decade in developed countries; and grand multiparity accounts for 10-30% of all pregnancies in some regions of Africa and Asia.

Adolescent Pregnancy

Definition and Epidemiology

Adolescent pregnancy refers to pregnancy occurring in females aged 10-19 years. This developmental period is characterized by significant physiological and psychological transitions, making pregnancy particularly challenging. Worldwide, approximately 21 million girls aged 15-19 become pregnant each year, with 12 million giving birth. The majority (95%) of adolescent pregnancies occur in low and middle-income countries.

Classification of adolescent pregnancy:

- Early adolescence: 10-14 years (highest risk category)

- Middle adolescence: 15-17 years (moderate risk)

- Late adolescence: 18-19 years (lower risk compared to other adolescent groups)

Risk factors for adolescent pregnancy include socioeconomic disadvantage, low educational attainment, family history of teenage pregnancy, early sexual debut, sexual abuse, limited access to contraception, and cultural factors that promote early marriage and childbearing. The high-risk pregnancy status of adolescents stems from both physiological immaturity and psychosocial factors.

Physiological Considerations

Adolescent pregnancy presents unique physiological challenges due to the ongoing developmental processes in the adolescent body. The competing nutritional demands of pregnancy and adolescent growth can create complications.

| Physiological System | Developmental Status in Adolescence | Implications for Pregnancy |

|---|---|---|

| Skeletal System | Ongoing bone growth; pelvic growth may be incomplete | Increased risk of cephalopelvic disproportion; potential for difficult vaginal delivery |

| Reproductive System | Immature uterine and cervical development, especially in early adolescents | Higher rates of preterm labor; increased risk of cervical incompetence |

| Cardiovascular System | Developing cardiovascular capacity | Potentially reduced ability to meet increased cardiac output demands of pregnancy |

| Nutritional Status | Increased nutritional requirements for adolescent growth | Competition between maternal growth needs and fetal development needs; increased risk of nutritional deficiencies |

| Endocrine System | Ongoing maturation of hormonal feedback systems | Potentially unstable hormonal patterns affecting pregnancy regulation |

The physiological immaturity is particularly pronounced in early adolescents (10-14 years), for whom pregnancy physiologically constitutes a high-risk pregnancy regardless of other factors. For late adolescents (18-19 years), physiological risks are often comparable to those of adult women, though psychosocial risks may remain elevated.

Maternal and Fetal Risks

Maternal Risks

- Pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia (1.5-2 times higher risk)

- Anemia (2-3 times higher prevalence)

- Urinary tract infections (increased susceptibility)

- Obstructed labor (especially in young adolescents with immature pelvic development)

- Higher rates of cesarean delivery

- Postpartum hemorrhage

- Obstetric fistula (particularly in regions with limited healthcare access)

- Higher maternal mortality (pregnancy is the leading cause of death for girls aged 15-19 in many developing countries)

- Mental health issues (postpartum depression affects up to 25% of adolescent mothers)

Fetal and Neonatal Risks

- Preterm birth (11% in adolescents vs 7-8% in adult women)

- Low birth weight (increased risk of 1.5-2 times)

- Intrauterine growth restriction

- Perinatal mortality (higher rates, especially in early adolescents)

- Congenital anomalies (increased risk possibly related to poor nutrition)

- Birth asphyxia (higher incidence rate)

- Neonatal intensive care admissions (increased likelihood)

- Developmental delays in infancy and early childhood

- Reduced breastfeeding initiation and duration

Critical Concern: The risk of maternal death among adolescents under 16 years is four times higher than among women in their twenties. Even adolescents aged 16-19 face mortality risks twice as high as women aged 20-24 years.

Nursing Assessment and Interventions

Comprehensive nursing care for pregnant adolescents requires a holistic approach that addresses both physiological and psychosocial needs.

TEEN-CARE Approach for Adolescent Pregnancy

- T: Trust – Establish a non-judgmental, confidential relationship

- E: Education – Provide age-appropriate information about pregnancy, labor, and parenting

- E: Engagement – Involve supportive family members and partners when possible

- N: Nutrition – Assess nutritional status and address increased requirements

- C: Complications – Monitor closely for pregnancy complications

- A: Advocacy – Connect with social services and educational resources

- R: Resources – Identify community support systems

- E: Empowerment – Foster decision-making skills and self-efficacy

Key Nursing Interventions:

| Domain | Assessment | Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Health |

|

|

| Psychosocial Health |

|

|

| Labor and Delivery |

|

|

| Postpartum |

|

|

Prevention Strategies

Prevention of adolescent pregnancy requires multifaceted approaches at individual, family, community, and policy levels.

Primary Prevention (Before Pregnancy)

- Comprehensive sexuality education in schools

- Access to youth-friendly reproductive health services

- Development of life skills and future orientation

- Community-based programs targeting high-risk youth

- Parent-child communication about sexuality

- Addressing gender inequality and social determinants

- Access to affordable contraception

Secondary Prevention (During Pregnancy)

- Early identification and engagement in prenatal care

- Multidisciplinary approach involving healthcare providers, social workers, educators

- School-based programs for pregnant teens

- Addressing nutritional needs

- Mental health support

- Development of birth plan appropriate for adolescents

Tertiary Prevention (After Pregnancy)

- Prevention of rapid repeat pregnancy through effective contraception

- Support for continuing education

- Parenting skills development

- Economic empowerment programs

- Long-term follow-up of mother and child

- Integration of pediatric care with maternal care

Nurses play a crucial role in reducing the incidence and impact of high-risk pregnancy among adolescents through education, advocacy, and direct care. Their position in schools, communities, and healthcare settings allows them to implement prevention strategies at all levels.

Elderly Primigravida

Definition and Trends

Elderly primigravida refers to a woman who experiences her first pregnancy at or after the age of 35 years. While the term “elderly” may seem inappropriate in current social context, it remains in medical literature to designate this high-risk pregnancy category. Alternative terms include “advanced maternal age primigravida” or “mature primigravida.”

Historical Perspective: The age threshold defining elderly primigravida has evolved over time. In the early 1900s, women over 25 years having their first child were considered elderly primigravida. By the 1950s-60s, the age was revised to 30 years, and since the 1980s, 35 years has been the established threshold.

The prevalence of elderly primigravida has been steadily increasing globally, particularly in developed countries. This trend is attributed to several societal factors:

- Pursuit of higher education and career development

- Delayed marriage and partnership

- Economic considerations and desire for financial stability

- Advances in reproductive technologies enabling later pregnancies

- Changing social norms regarding family formation timing

- Improved contraceptive access allowing precise pregnancy planning

In many developed countries, the mean age at first birth has increased by 4-5 years over the past three decades. In the United States, births to women aged 35 and older have increased by 23% since 2000, while births to women under 25 have decreased by 29% during the same period.

Physiological Considerations

Advanced maternal age brings specific physiological considerations that contribute to the classification of elderly primigravida as a high-risk pregnancy.

| Physiological System | Age-Related Changes | Implications for Pregnancy |

|---|---|---|

| Reproductive System | Diminished ovarian reserve; reduced oocyte quality; decreased uterine blood flow; reduced myometrial efficiency | Increased risk of chromosomal abnormalities; higher rates of infertility; reduced placental perfusion; potentially less efficient labor |

| Cardiovascular System | Reduced cardiac reserve; decreased vascular compliance; higher baseline blood pressure | Reduced ability to adapt to increased blood volume; higher risk of hypertensive disorders; increased cardiac strain |

| Renal System | Decreased renal reserve; slight age-related reduction in GFR | Less capacity to manage increased renal workload of pregnancy; higher risk of renal complications |

| Musculoskeletal System | Reduced muscle tone; decreased joint flexibility; potential for pre-existing musculoskeletal conditions | Increased discomfort from pregnancy-related posture changes; higher risk of back pain; recovery challenges |

| Metabolic Function | Decreased insulin sensitivity; altered glucose metabolism; increased baseline adiposity | Higher risk of gestational diabetes; increased likelihood of metabolic complications; challenges in weight management |

The physiological adaptations to pregnancy that occur easily in younger women may be more challenging for the elderly primigravida. The body has less physiological reserve capacity to accommodate the significant cardiovascular, respiratory, and metabolic demands of pregnancy.

Important to note that chronological age alone does not determine risk; physiological age, pre-pregnancy health status, and presence of pre-existing medical conditions are equally important factors in assessing individual risk in elderly primigravida.

Maternal and Fetal Risks

Maternal Risks

- Hypertensive disorders: 2-3 times higher risk of preeclampsia compared to younger women

- Gestational diabetes: Risk increases progressively with age (10-15% incidence versus 3-5% in younger women)

- Placental abnormalities: Higher rates of placenta previa (2-3 times increased risk)

- Cesarean delivery: 40-60% cesarean rate in elderly primigravida versus 20-30% in younger primigravida

- Prolonged labor: Reduced myometrial efficiency may contribute to longer labor

- Pre-existing chronic conditions: Higher likelihood of chronic hypertension, diabetes, thyroid disorders

- Multiple gestation: Higher rates due to natural physiological changes and increased use of assisted reproductive technologies

- Postpartum hemorrhage: 1.5-2 times increased risk

- Maternal mortality: 2-3 times higher compared to women aged 20-30

Fetal and Neonatal Risks

- Chromosomal abnormalities: Exponentially increasing risk with maternal age (e.g., Down syndrome risk is 1:1250 at age 25, 1:400 at age 35, and 1:100 at age 40)

- Congenital anomalies: Increased risk independent of chromosomal issues

- Intrauterine growth restriction: Higher incidence due to placental insufficiency

- Preterm birth: 1.5-2 times increased risk

- Low birth weight: Related to both iatrogenic and spontaneous preterm delivery

- Macrosomia: Higher risk if maternal gestational diabetes is present

- Stillbirth: Risk progressively increases with maternal age, particularly after 40 years

- Neonatal intensive care admission: Higher rates due to complications

- Perinatal mortality: Approximately 1.5-2 times higher than in younger women

Risk Progression: Research indicates that risks increase progressively with maternal age rather than suddenly at age 35. Women aged 35-37 have slightly elevated risks, while those aged 40+ have substantially higher risks, classifying them as higher-risk within the elderly primigravida category.

Prenatal Screening and Testing

Due to increased risks, elderly primigravida undergo more extensive prenatal screening and testing than younger women, particularly focused on genetic abnormalities and maternal health conditions.

| Screening/Testing Type | Timing | Purpose | Considerations for Elderly Primigravida |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Trimester Combined Screening | 11-14 weeks | Assessment of risk for chromosomal abnormalities (trisomies 21, 18, 13) | Standard for elderly primigravida; combines nuchal translucency ultrasound with serum markers (PAPP-A, free β-hCG) |

| Cell-Free DNA Testing (NIPT) | After 10 weeks | Non-invasive screening for common chromosomal abnormalities | Higher positive predictive value in elderly primigravida due to higher baseline risk; increasingly offered as first-line screening |

| Chorionic Villus Sampling (CVS) | 10-13 weeks | Diagnostic testing for chromosomal abnormalities | Higher utilization rates in elderly primigravida; offered regardless of screening results for women >40 in some practice settings |

| Amniocentesis | 15-20 weeks | Diagnostic testing for chromosomal and certain genetic disorders | More commonly performed in elderly primigravida; risk of procedure (miscarriage) lower than baseline age-related risk |

| Detailed Anatomy Scan | 18-22 weeks | Comprehensive assessment of fetal anatomy | Often performed with greater detail and attention in elderly primigravida; may involve maternal-fetal medicine specialist |

| Glucose Challenge Test | 24-28 weeks | Screening for gestational diabetes | Earlier testing (at first prenatal visit) often recommended, with repeat testing at 24-28 weeks if initial results normal |

| Growth Scans | Third trimester (serial) | Monitoring fetal growth | More frequent monitoring for IUGR and macrosomia; typically every 3-4 weeks in third trimester |

| Fetal Surveillance | Third trimester | Assessment of fetal well-being | Earlier initiation of NST/BPP (often at 32-34 weeks); more frequent monitoring |

ADVANCED Prenatal Care Mnemonic for Elderly Primigravida

- A: Assessment of pre-existing conditions early in pregnancy

- D: Detailed ultrasound evaluation of fetal anatomy

- V: Vigilant monitoring of maternal health parameters

- A: Aneuploidy screening and diagnostic testing options

- N: Nutritional counseling for optimal maternal-fetal outcomes

- C: Cardiovascular system monitoring throughout pregnancy

- E: Education about age-related risks and management options

- D: Diabetes screening and management protocols

Nursing Assessment and Interventions

Nursing care for elderly primigravida requires specialized assessment and interventions to address the unique physical and psychosocial aspects of this high-risk pregnancy category.

| Domain | Assessment | Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Health |

|

|

| Psychosocial Health |

|

|

| Nutritional Status |

|

|

| Fetal Monitoring |

|

|

Special Considerations for Elderly Primigravida:

- Address concerns about energy levels for parenthood at advanced age

- Provide evidence-based information to differentiate age-related myths from real risks

- Facilitate informed decision-making regarding interventions and monitoring

- Prepare for possibility of medical intervention during labor and birth

- Discuss advance care planning given slightly elevated mortality risks

- Connect with resources for age-appropriate postpartum support

Peripartum Management

Labor, delivery, and postpartum management for elderly primigravida requires a tailored approach due to the higher risk profile of this population.

Labor Management Considerations

- Consideration for scheduled induction between 39-40 weeks (especially for women ≥40 years) to reduce stillbirth risk

- Continuous electronic fetal monitoring throughout labor

- Lower threshold for cesarean delivery for non-reassuring fetal status

- Awareness of potentially longer labor due to reduced myometrial efficiency

- More conservative management of labor dystocia

- Enhanced pain management options considering lower pain tolerance with age

- Close monitoring for signs of hypertensive crisis during labor

- Prophylactic measures to reduce postpartum hemorrhage risk

Postpartum Considerations

- Heightened surveillance for postpartum hemorrhage

- Extended monitoring of vital signs post-delivery

- Earlier ambulation to reduce thromboembolism risk

- Enhanced lactation support (may have delayed milk production)

- Additional rest periods to address increased fatigue

- Screening for postpartum depression and anxiety (risks may be higher)

- Physical therapy referral for more challenging recovery

- Extended postpartum follow-up schedule

Despite the classification as high-risk pregnancy, it’s important to note that most elderly primigravida have successful outcomes. The key to optimizing these outcomes is appropriate risk assessment, enhanced surveillance, timely intervention, and addressing the unique physical and psychosocial aspects of pregnancy at advanced maternal age.

Balancing Benefits: While elderly primigravida face increased risks, they often demonstrate advantages in terms of psychological readiness for parenthood, financial stability, relationship security, and health-promoting behaviors during pregnancy. Nurses should acknowledge these strengths while monitoring for age-related complications.

Grand Multiparity

Definition and Classification

Grand multiparity refers to a woman who has had five or more previous viable pregnancies (regardless of outcome). This obstetric category represents another important high-risk pregnancy population requiring specialized care and monitoring.

Parity Classification

- Nullipara: A woman who has never given birth to a viable offspring

- Primipara: A woman who has given birth once to a viable offspring

- Multipara: A woman who has given birth two to four times to viable offspring

- Grand multipara: A woman who has given birth five to nine times to viable offspring

- Great grand multipara: A woman who has given birth ten or more times to viable offspring

The prevalence of grand multiparity varies widely across different regions and populations:

- Low-income countries: 10-30% of pregnancies

- Middle-income countries: 5-15% of pregnancies

- High-income countries: Generally below 2-4% of pregnancies

Grand multiparity is associated with certain demographic and social factors:

- Religious beliefs that discourage contraception

- Cultural values favoring large families

- Limited access to or education about family planning

- Lower socioeconomic status and educational achievement

- Early marriage and childbearing initiation

- Rural residence

Physiological Changes

Multiple pregnancies and deliveries result in significant physiological changes that can affect subsequent pregnancies and contribute to the classification of grand multiparity as a high-risk pregnancy.

| Physiological System | Changes Associated with Grand Multiparity | Implications for Current Pregnancy |

|---|---|---|

| Uterine Structure | Decreased myometrial tone; laxity of supporting ligaments; potential scarring from previous deliveries | Increased risk of uterine atony; malposition of fetus; abnormal labor patterns |

| Abdominal Wall | Weakened rectus muscles; potential diastasis recti; reduced abdominal tone | Less effective pushing during second stage; pendulous abdomen affecting fetal position |

| Vascular System | Increased venous distensibility from repeated pregnancies; potential residual varicosities | Higher risk of venous insufficiency; increased edema; varicose veins; hemorrhoids |

| Pelvic Floor | Progressive weakening of pelvic floor muscles; potential damage from previous deliveries | Increased risk of prolapse; stress incontinence; pelvic floor dysfunction |

| Placentation | Potential scarring at previous placental implantation sites; uterine scarring from previous deliveries | Higher risk of placenta previa and placenta accreta spectrum disorders |

| Nutritional Status | Potential depletion of nutritional reserves from closely spaced pregnancies; reduced inter-pregnancy recovery time | Increased risk of nutritional deficiencies, especially iron, calcium, and folate; higher anemia risk |

The cumulative effect of multiple pregnancies produces a physiological profile distinct from both nulliparous women and those of lower parity. However, it’s important to note that physiological adaptations vary widely among grand multiparas based on inter-pregnancy intervals, maternal age, nutritional status, and overall health.

Maternal and Fetal Risks

Maternal Risks

- Anemia: 2-3 times more common, especially with short interpregnancy intervals

- Malpresentation: Higher rates of abnormal fetal positioning (10-15% versus 3-5% in lower parity)

- Placenta previa: 2-4 times increased risk

- Placenta accreta spectrum: Progressively increasing risk with increasing parity, especially with previous cesarean deliveries

- Uterine rupture: Risk increases with each subsequent pregnancy, especially with prior uterine surgery

- Postpartum hemorrhage: 2-5 times increased risk due to uterine atony

- Precipitous labor: Higher rates of rapid labor and delivery (potential for unattended birth)

- Gestational diabetes: Increased risk, particularly in women with advanced age

- Obstetric prolapse: Higher rates of uterine, bladder, and rectal prolapse

Fetal and Neonatal Risks

- Macrosomia: Increased frequency (20-30% versus 10% in lower parity)

- Fetal growth restriction: Paradoxically also increased, likely related to placental insufficiency in some cases

- Birth trauma: Higher rates due to macrosomia, malpresentation, and precipitous delivery

- Cord prolapse: Increased risk related to malpresentation and engaged presenting part

- Perinatal mortality: 1.5-2 times higher rate, forming a U-shaped curve with highest risk in nulliparas and grand multiparas

- Preterm birth: Slightly elevated risk

- Congenital anomalies: Higher rates reported in some studies

- Abnormal Apgar scores: More frequent need for neonatal resuscitation

Critical Risk Profile: Great grand multiparity (10+ births) is associated with substantially higher risks than grand multiparity, particularly for postpartum hemorrhage, placental abnormalities, and maternal mortality. In some studies, maternal mortality is 5-10 times higher in great grand multiparas compared to women of lower parity.

Common Complications

Several complications deserve special attention in the context of grand multiparity due to their increased prevalence and potential severity.

MULTIPARA Risks Mnemonic

- M: Malpresentation (increased risk of non-vertex presentations)

- U: Uterine atony leading to postpartum hemorrhage

- L: Lax abdominal muscles affecting fetal positioning

- T: Traumatic birth risks due to precipitous labor

- I: Iron deficiency anemia from nutritional depletion

- P: Placental abnormalities (previa, accreta)

- A: Abnormal labor pattern (often rapid)

- R: Rupture of uterus (increased risk with history of cesarean)

- A: Advanced maternal age complications (often co-occurring)

Spotlight: Postpartum Hemorrhage in Grand Multiparity

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is one of the most significant risks in grand multiparity, with rates 2-5 times higher than in women of lower parity. The primary mechanism is uterine atony, resulting from:

- Decreased myometrial tone and contractility

- Over-distension of the uterus (common with larger babies)

- Reduced elasticity of uterine muscle tissue

- Exhaustion of the myometrium after multiple pregnancies

Prevention strategies include:

- Active management of third stage of labor for ALL grand multiparas

- Prophylactic oxytocin administration

- Consideration of prophylactic tranexamic acid in high-risk cases

- Close monitoring of blood loss

- Early intervention at first signs of excessive bleeding

- Ensuring IV access and blood products availability

Spotlight: Placenta Accreta Spectrum Disorders

Grand multiparas have an elevated risk of placenta accreta spectrum disorders (abnormal placental attachment), particularly those with previous cesarean deliveries. The risk increases dramatically when grand multiparity co-occurs with placenta previa and previous cesarean delivery.

- Risk factors: Each prior cesarean delivery, advanced maternal age, prior uterine surgery, prior placenta previa

- Screening: Enhanced ultrasound surveillance for all grand multiparas with anterior or previa placentation

- Management: May require multidisciplinary approach, planned cesarean hysterectomy, and availability of blood products

- Mortality risk: 7% maternal mortality without appropriate preparation and management

Nursing Assessment and Interventions

Comprehensive nursing care for grand multiparas requires attention to both the physical risks of this high-risk pregnancy category and the unique psychosocial factors often present.

| Domain | Assessment | Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Prenatal Assessment |

|

|

| Psychosocial Assessment |

|

|

| Labor and Delivery |

|

|

| Postpartum Care |

|

|

Strengths-Based Approach:

While focusing on risks is important, nurses should also recognize and leverage the strengths that grand multiparas bring to their pregnancy and birth:

- Experiential knowledge from previous pregnancies

- Often greater confidence with infant care

- Realistic expectations about labor, birth, and postpartum recovery

- Developed coping strategies for pregnancy discomforts

- Established maternal role identity

Acknowledging these strengths while providing education about specific risks helps create a balanced care approach.

Labor Management

Managing labor in grand multiparas requires awareness of the unique labor patterns and risks associated with this high-risk pregnancy category.

First Stage Considerations

- Often shorter first stage (may progress rapidly)

- Continuous fetal monitoring recommended due to higher cord accident risk

- Careful assessment of fetal presentation and position

- Vigilance for hypotonic contractions (can be common)

- Judicious use of oxytocin (increased sensitivity)

- Close monitoring if membranes rupture (higher cord prolapse risk)

- Early epidural consideration if desired (risk of precipitous delivery)

Second and Third Stage Considerations

- Typically rapid second stage

- Potential ineffective pushing due to weakened abdominal muscles

- Increased risk of perineal lacerations with precipitous delivery

- Active management of third stage for ALL grand multiparas

- Prophylactic oxytocin administration

- Vigilant monitoring for excessive bleeding

- Extended observation period postpartum (minimum 2 hours)

- Lower threshold for intervention with excessive bleeding

Labor Pattern Paradox: While many grand multiparas experience rapid labor, some experience dysfunctional labor patterns due to uterine muscle fatigue or over-distension. This dichotomous pattern (either very fast or abnormally slow) requires careful assessment and individualized management.

Recognition of the unique risks associated with grand multiparity allows for appropriate preparation and timely intervention when needed, while still supporting the physiologic birth process when safely possible.

Comparative Analysis of Special Obstetric Populations

Each of the three high-risk pregnancy categories discussed—adolescent pregnancy, elderly primigravida, and grand multiparity—presents distinct challenges yet also shares some common risk factors and management principles.

| Feature | Adolescent Pregnancy | Elderly Primigravida | Grand Multiparity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Physiological Risk Factors | Physiological immaturity; competing nutritional demands; incomplete pelvic growth | Age-related decline in physiological reserve; increased chromosomal abnormality risk | Uterine muscle fatigue; weakened abdominal and pelvic muscles; repeated placental implantation |

| Primary Psychosocial Considerations | Interrupted developmental tasks; educational disruption; limited social support; financial concerns | Career integration; anxiety regarding age-related risks; typically higher financial stability | Caregiver fatigue; financial strain of large family; divided attention among children |

| Key Maternal Risks | Preeclampsia; anemia; cephalopelvic disproportion; obstructed labor | Gestational diabetes; hypertensive disorders; cesarean delivery; placenta previa | Postpartum hemorrhage; malpresentation; placenta accreta; uterine rupture |

| Key Fetal/Neonatal Risks | Preterm birth; low birth weight; IUGR; higher perinatal mortality | Chromosomal abnormalities; congenital anomalies; stillbirth; macrosomia with GDM | Malpresentation; cord accidents; birth trauma; macrosomia |

| Common Nutritional Concerns | Inadequate intake; competition between maternal growth and fetal development; higher calcium needs | Often better baseline nutrition; potential for excessive weight gain; increased GDM risk | Nutritional depletion from multiple pregnancies; iron and calcium deficiency |

| Typical Labor Pattern | Potentially longer due to immature pelvic structure and inefficient uterine action (especially in early adolescents) | Often longer first stage; higher intervention rates; increased labor dystocia; higher cesarean rate | Typically rapid labor (precipitous); shorter first and second stages; potential for unattended birth |

| Primary Prevention Focus | Prevention of adolescent pregnancy through education, contraception access, and addressing social determinants | Preconception counseling; genetic counseling; baseline health optimization; addressing modifiable risk factors | Family planning education; adequate birth spacing; nutritional replenishment between pregnancies |

| Key Support Needs | Educational continuity; parenting skills; financial support; social reintegration | Anxiety management; advanced genetic counseling; work-life balance preparation | Household management strategies; childcare for existing children; family integration planning |

| Global Prevalence Trend | Decreasing in developed countries; stubbornly high in many developing regions | Steadily increasing globally, especially in developed countries | Decreasing in developed countries; remains common in certain developing regions |

Overlapping Concerns Across Categories

Some high-risk pregnancy factors are common across multiple special populations:

- Anemia: Higher rates in both adolescent pregnancy and grand multiparity

- Hypertensive disorders: Elevated risk in both adolescent pregnancy and elderly primigravida

- Preterm birth: Increased rates across all three groups

- Psychological adaptation: Each group faces unique but significant psychological challenges

- Socioeconomic factors: Often play a crucial role in outcomes across all categories

- Need for enhanced monitoring: All three groups benefit from more frequent surveillance

Understanding both the unique and overlapping characteristics of these three high-risk pregnancy categories helps nurses provide tailored, evidence-based care while recognizing common principles that apply across groups.

Case Studies and Clinical Applications

Case 1: Adolescent Pregnancy

Patient: Maria, 15-year-old primigravida at 28 weeks gestation

Presenting Issues:

- Lives with single mother who works long hours

- Attending school irregularly due to morning sickness

- Hemoglobin 10.2 g/dL (mild anemia)

- Blood pressure trending upward at recent visits

- Concerned about labor pain and parenting skills

Nursing Approach:

- Coordinate with school nurse for educational continuity

- Screen for preeclampsia at each visit

- Prescribe iron supplementation and nutrition counseling

- Connect with teen parenting program

- Involve boyfriend and mother in prenatal education

- Address fears about labor through age-appropriate education

Case 2: Elderly Primigravida

Patient: Susan, 38-year-old primigravida at 22 weeks gestation

Presenting Issues:

- Conceived via IVF after 3 years of infertility

- Executive position with high work demands

- Failed glucose challenge test; diagnosed with GDM

- High anxiety about chromosomal abnormalities

- History of fibroid removed 5 years ago

Nursing Approach:

- Provide detailed information about GDM management

- Review NIPT results and explain limitations

- Establish balanced work-rest schedule

- Monitor growth for macrosomia risk

- Refer to maternal-fetal medicine for consultation

- Discuss birth planning with contingencies for complications

Case 3: Grand Multiparity

Patient: Fatima, 34-year-old G6P5 at 36 weeks gestation

Presenting Issues:

- History of precipitous labor with last delivery (30 minutes)

- Lives 45 minutes from hospital

- Previous postpartum hemorrhage requiring transfusion

- Hemoglobin 9.8 g/dL despite iron supplementation

- Ultrasound shows estimated fetal weight of 4200g

Nursing Approach:

- Develop detailed birth plan with early hospital admission

- Arrange childcare plan for other children

- Alert blood bank about history of PPH

- Review warning signs that require immediate attention

- Discuss induction possibility at 39 weeks

- Prepare emergency delivery kit for home/car

Clinical Decision-Making Framework for High-Risk Pregnancy Categories

- Identify category-specific risk factors through thorough history and current assessment

- Establish individualized care plan addressing both physiological and psychosocial needs

- Determine appropriate monitoring frequency and methods based on risk profile

- Develop contingency plans for potential complications

- Coordinate multidisciplinary approach when needed (social services, specialists, etc.)

- Provide anticipatory guidance specific to the high-risk pregnancy category

- Implement preventive measures for common complications in each category

- Evaluate effectiveness of interventions and adjust plan accordingly

Global Best Practices

Around the world, various approaches have been developed to address the specific needs of these high-risk pregnancy populations. These best practices provide valuable insights for nursing care.

Adolescent Pregnancy Best Practices

Chile’s Comprehensive Adolescent Pregnancy Program

- Integration of prenatal care with educational continuity

- Peer support groups facilitated by young mothers

- Male partner involvement initiatives

- Specialized adolescent birth centers with age-appropriate environment

- School reintegration protocols post-delivery

- Long-term contraceptive provision post-delivery

This program reduced repeat adolescent pregnancy rates by 30% and improved educational outcomes for teen mothers.

Elderly Primigravida Best Practices

Japan’s “Advanced Maternal Age Support System”

- Specialized AMA clinics with extended appointment times

- Comprehensive preconception counseling and testing

- Work-life balance support with flexible prenatal scheduling

- Age-specific prenatal classes addressing unique concerns

- Extended postpartum home visits focusing on maternal recovery

- Integration of traditional recovery practices with modern medicine

This approach has resulted in improved maternal satisfaction and reduced complication rates in women over 35.

Grand Multiparity Best Practices

Jordan’s “Safe Grand Multiparity Initiative”

- Enhanced hemorrhage prevention protocols for all grand multiparas

- Community health worker home monitoring program

- Iron supplementation program starting early in pregnancy

- Birth planning with transportation arrangements

- Family-centered approach involving older children

- Respectful maternity care framework acknowledging experience

This program reduced PPH rates by 25% and maternal mortality by 40% among grand multiparas.

Common Elements of Successful Programs

Despite addressing different high-risk pregnancy populations, successful programs worldwide share certain characteristics:

- Person-centered approach: Recognizing the unique needs of individuals within risk categories

- Continuity of care: Ensuring consistent caregivers throughout the perinatal period

- Social support enhancement: Actively building support networks around vulnerable women

- Cultural sensitivity: Adapting interventions to cultural contexts and beliefs

- Interdisciplinary collaboration: Involving multiple disciplines beyond medical care

- Extended timeframe: Providing support beyond the immediate postpartum period

- Prevention orientation: Focusing on preventing complications rather than just treating them

Conclusion

Understanding the unique characteristics, risks, and management approaches for adolescent pregnancy, elderly primigravida, and grand multiparity is essential for providing optimal nursing care to these high-risk pregnancy populations. Each category presents distinct physiological, psychological, and social challenges that require tailored interventions and support strategies.

Nurses play a pivotal role in identifying risks early, implementing preventive measures, providing evidence-based care, offering psychosocial support, and coordinating multidisciplinary services for these populations. By utilizing a holistic, person-centered approach that addresses both medical and psychosocial dimensions, nurses can significantly improve outcomes for mothers and babies in these high-risk categories.

The field continues to evolve as new research emerges and care models adapt to changing demographics and healthcare systems. Ongoing professional development, critical assessment of evidence, and integration of global best practices will ensure that nursing care for these special obstetric populations continues to improve, ultimately reducing maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality worldwide.

References

- World Health Organization. (2020). Adolescent pregnancy. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2020). Pregnancy Over Age 35. ACOG Patient Pamphlet.

- Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. (2019). High-risk pregnancy care, research, and education for over 35 years.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. (2018). Induction of Labour at Term in Older Mothers. Scientific Impact Paper No. 34.

- Mgaya, A. H., Massawe, S. N., Kidanto, H. L., & Mgaya, H. N. (2013). Grand multiparity: is it still a risk in pregnancy? BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 13(1), 1-8.

- Fleming, N., O’Driscoll, T., Becker, G., & Spitzer, R. F. (2015). Adolescent Pregnancy Guidelines. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 37(8), 740-756.

- Carolan, M. (2013). Maternal age ≥45 years and maternal and perinatal outcomes: A review of the evidence. Midwifery, 29(5), 479-489.

- Ganchimeg, T., Ota, E., Morisaki, N., Laopaiboon, M., Lumbiganon, P., Zhang, J., … & WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal Newborn Health Research Network. (2014). Pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers: a World Health Organization multicountry study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 121, 40-48.

- Alshahrani, M. S., Aladhadh, M., Alqarni, S., Alenezi, S., & Alanazi, A. (2019). Grand multiparity: Risk factors, maternal and neonatal outcomes in a tertiary hospital. International Journal of Medicine in Developing Countries, 3(6), 512-517.

- Cavazos-Rehg, P. A., Krauss, M. J., Spitznagel, E. L., Bommarito, K., Madden, T., Olsen, M. A., … & Bierut, L. J. (2015). Maternal age and risk of labor and delivery complications. Maternal and child health journal, 19(6), 1202-1211.

- World Health Organization. (2018). WHO recommendations: intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. World Health Organization.

- Ogawa, K., Matsushima, S., Urayama, K. Y., Kikuchi, N., Nakamura, N., Tanigaki, S., … & Morisaki, N. (2017). Association between adolescent pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes, a multicenter cross sectional Japanese study. Scientific reports, 7(1), 1-8.

- Lean, S. C., Derricott, H., Jones, R. L., & Heazell, A. E. P. (2017). Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one, 12(10), e0186287.

- Koo, Y. J., Ryu, H. M., Yang, J. H., Lim, J. H., Lee, J. E., Kim, M. Y., & Chung, J. H. (2012). Pregnancy outcomes according to increasing maternal age. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 51(1), 60-65.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2019). Care of Adolescent Parents and Their Children. Pediatrics, 144(6), e20193150.