Puerperal Sepsis

Comprehensive Guide for Nursing Students

Puerperal sepsis is a life-threatening condition defined as infection of the genital tract occurring at any time between the rupture of membranes or labor and the 42nd day postpartum. It is one of the major causes of maternal mortality worldwide, ranking second behind postpartum hemorrhage, accounting for approximately 10-15% of maternal deaths globally.

This comprehensive guide aims to equip nursing students with essential knowledge about puerperal sepsis, including its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment approaches, and nursing care plans to effectively manage and prevent this potentially fatal condition.

Table of Contents

1. Historical Perspective

Semmelweis’ Discovery: The Birth of Infection Control

Key Historical Milestone: Hungarian obstetrician Dr. Ignaz Phillip Semmelweis (1818-1865) was the first to identify the mode of transmission of puerperal sepsis.

In the 1840s, Semmelweis observed a stark difference in maternal mortality rates between two clinics at Vienna General Hospital:

- Clinic 1: Staffed by male physicians and medical students who performed autopsies — had mortality rates of 98.4 per 1000 births

- Clinic 2: Staffed by midwives who did not perform autopsies — had mortality rates of only 36.2 per 1000 births

Semmelweis hypothesized that physicians were transferring “cadaveric particles” from autopsies to women in labor. In May 1847, he implemented mandatory handwashing with chlorinated lime solution before examining patients, resulting in a dramatic reduction in maternal mortality in Clinic 1 to match the rates of Clinic 2.

This breakthrough occurred before the development of germ theory, making Semmelweis a pioneer in infection control. Despite his significant finding, his theory was rejected by the medical establishment of the time. Only years later, with the advancement of bacteriology and germ theory, was the importance of his discovery fully recognized.

Today, Semmelweis is known as “the savior of mothers” and his discovery forms the foundation of modern infection prevention practices in healthcare.

2. Definition and Epidemiology

Understanding Puerperal Sepsis

Definition: Puerperal sepsis is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as infection of the genital tract occurring at any time between the rupture of membranes or labor and the 42nd day postpartum, in which two or more of the following are present:

- Pelvic pain

- Fever (oral temperature ≥38.5°C/101.3°F on any occasion)

- Abnormal vaginal discharge (e.g., presence of pus or foul odor)

- Delay in the reduction of the size of the uterus (subinvolution)

Global Burden:

- Puerperal sepsis is one of the top five causes of maternal mortality worldwide

- Accounts for approximately 10-15% of all maternal deaths

- Globally, around 75,000 maternal deaths occur each year due to puerperal sepsis

- Highest incidence rates in low-income countries:

- Asia: 11.6%

- Africa: 9.7%

- South America: 7.7%

Figure 1: Global Distribution of Causes of Maternal Mortality

Incidence:

Incidence rates vary significantly depending on:

- Mode of delivery (5-10 times higher after cesarean section compared to vaginal delivery)

- Geographic location and healthcare quality

- Socioeconomic factors

- In developed countries with modern healthcare: 1-3% of live births

- In developing countries: up to 10% of deliveries may be complicated by puerperal sepsis

Note: The significant variation in reported incidence rates is partly due to differences in diagnostic criteria and reporting systems between countries.

3. Pathophysiology

Mechanism of Infection and Progression

Core Concept: Puerperal sepsis develops when bacteria gain access to normally sterile tissues of the genital tract during or after labor, leading to localized infection that can progress to systemic inflammation and sepsis.

Routes of Bacterial Invasion:

- Ascending infection: Most common route – bacteria from the vagina ascend into the uterine cavity

- Direct inoculation: During obstetric procedures, examinations, or surgical interventions

- Lymphatic spread: Through lymphatic channels to surrounding tissues

- Hematogenous spread: Via bloodstream from other infection sites

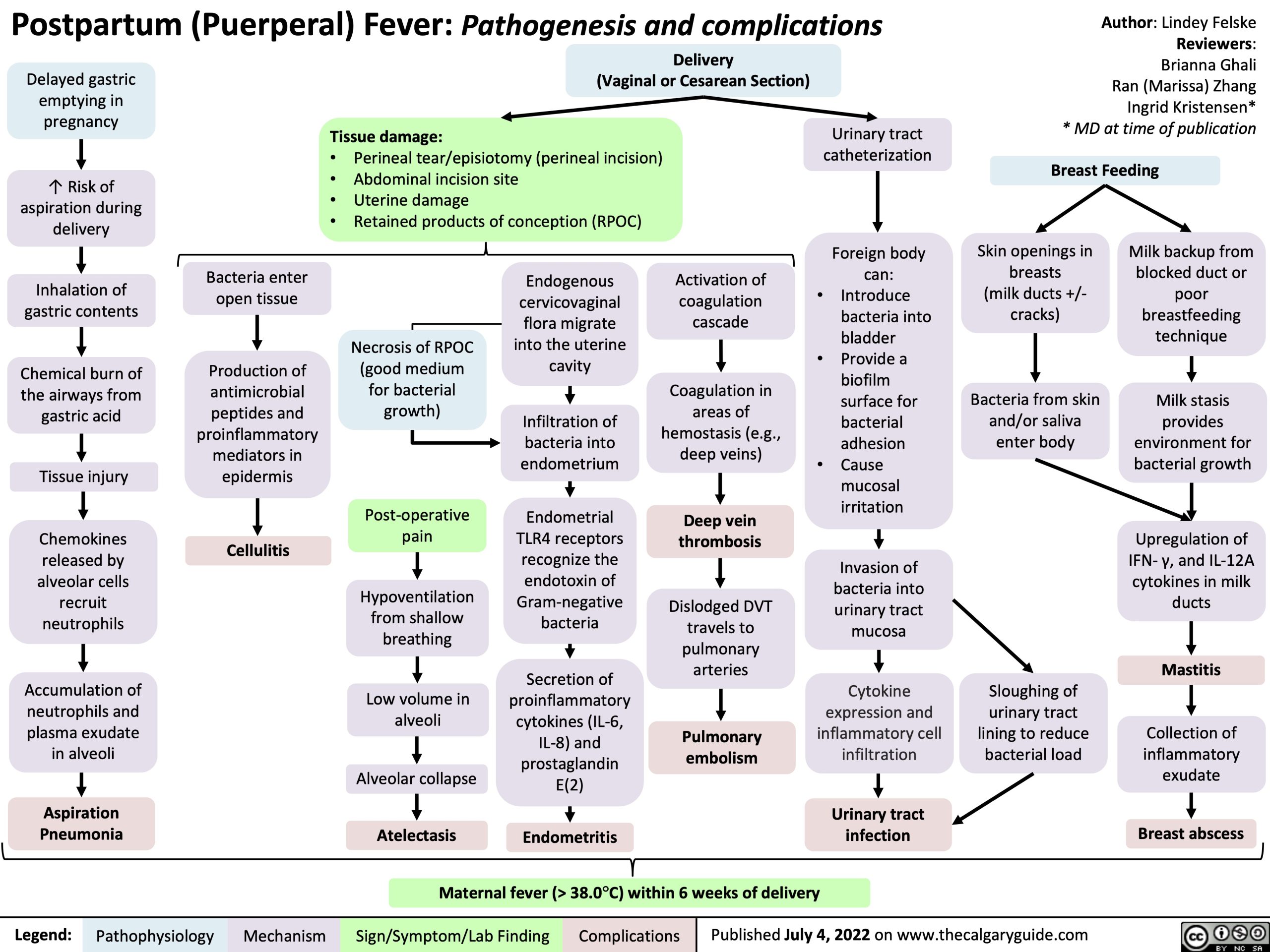

Figure 2: Pathophysiology of Puerperal Sepsis with routes of infection spread

Microbiology:

Puerperal sepsis is typically polymicrobial, involving both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria:

- Group A & B Streptococci: Historically significant cause (Group A strep was known as “the childbed fever”)

- Escherichia coli: Common pathogen from intestinal flora

- Staphylococcus aureus: Can cause severe infection and toxic shock syndrome

- Klebsiella pneumoniae: Particularly in healthcare-associated infections

- Anaerobes: Bacteroides, Peptostreptococcus, Clostridium species

- Enterococci: Especially in cases with prior antibiotic exposure

Progression of Infection:

- Endometritis: Initial infection of the endometrial lining

- Myometritis: Spread to the uterine muscle layer

- Parametritis: Extension to the broad ligament and pelvic cellular tissue

- Peritonitis: Infection of the peritoneal cavity

- Septicemia: Bacteria enter the bloodstream causing systemic infection

- Septic shock: Severe sepsis with tissue hypoperfusion and organ dysfunction

Systemic Inflammatory Response:

In severe cases, bacterial endotoxins and exotoxins trigger a systemic inflammatory cascade:

- Cytokine release: Pro-inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6) cause vasodilation and increased capillary permeability

- Endothelial damage: Leading to microvascular dysfunction

- Coagulation activation: Triggering the clotting cascade, potentially leading to DIC (Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation)

- Impaired tissue perfusion: Resulting in organ dysfunction

Figure 3: Pathophysiology of sepsis progression from localized infection to septic shock

Unique Factors in Puerperal Sepsis:

Several factors unique to the postpartum period increase susceptibility to infection:

- Placental site: Open wound with exposed vessels at the placental implantation site

- Immunological changes: Relative immunosuppression during pregnancy and postpartum period

- Tissue trauma: From delivery process, episiotomy, or cesarean incision

- Retained products: Placental fragments or blood clots provide excellent medium for bacterial growth

- Physiologic changes: Increased heart rate, decreased blood pressure, and leukocytosis can mask early signs of infection

4. Risk Factors

Predisposing Factors for Puerperal Sepsis

Key Concept: Risk factors for puerperal sepsis can be categorized into pre-existing patient factors, intrapartum factors, and postpartum factors.

Pre-existing Patient Factors:

- Malnutrition and anemia: Impair immune function and wound healing

- Obesity (BMI >30): Associated with impaired wound healing and increased surgical complications

- Diabetes mellitus: Affects immune function and increases susceptibility to infection

- Immunocompromised status: HIV infection, use of immunosuppressants

- Pre-existing genital tract infections: Bacterial vaginosis, group B streptococcal colonization

- Low socioeconomic status: Often associated with poor nutrition and limited access to healthcare

Intrapartum (During Labor and Delivery) Factors:

- Prolonged rupture of membranes (>18 hours): Allows ascending bacterial colonization

- Prolonged labor (>24 hours): Increases risk of tissue trauma and bacterial colonization

- Multiple vaginal examinations: Each examination increases risk of introducing pathogens

- Cesarean delivery: 5-20 times higher risk compared to vaginal delivery

- Intrauterine manipulation: Manual removal of placenta, internal version

- Traumatic delivery: Extensive tissue damage, hematoma formation

- Retained placental fragments: Provide medium for bacterial growth

- Poor aseptic techniques: During obstetric procedures

Figure 4: Relative Risk of Puerperal Sepsis by Factor (Based on Odds Ratios)

Postpartum Factors:

- Postpartum hemorrhage: Increases risk of infection and reduces host defenses

- Poor perineal hygiene: Allows bacterial colonization and ascension

- Invasive procedures: Catheterization, IV lines

- Wound hematoma: Provides excellent medium for bacterial growth

- Endometrial damage: From instrumentation or cesarean delivery

Healthcare System Factors:

- Limited access to healthcare: Delays in seeking care

- Poor infection control practices: In healthcare facilities

- Inadequate sterilization: Of medical instruments

- Overcrowded facilities: Increase risk of cross-infection

- Lack of trained personnel: For proper management of labor and delivery

Clinical Alert: The presence of multiple risk factors has a cumulative effect on increasing the likelihood of developing puerperal sepsis. Early identification of high-risk patients allows for implementation of preventive measures and close monitoring.

5. Clinical Manifestations

Signs and Symptoms

Key Concept: Clinical presentation of puerperal sepsis ranges from mild localized symptoms to severe systemic manifestations depending on the extent of infection and the causative organism.

Early Signs and Symptoms:

- Fever: Temperature ≥38°C (100.4°F) after the first 24 hours postpartum

- Pelvic or lower abdominal pain: Often described as dull, constant, or cramping

- Foul-smelling lochia: Abnormal odor, may become purulent

- Abnormal lochia volume: Either excessive or decreased

- Uterine tenderness: Pain on palpation of the uterine fundus

- Subinvolution of uterus: Delayed return to normal size

- Tachycardia: Pulse rate disproportionate to temperature

Signs of Progression and Spreading Infection:

- Parametritis: Pain and induration extending to the pelvic side wall

- Peritonitis: Generalized abdominal pain, rigidity, decreased bowel sounds

- Pelvic abscess: Fluctuant mass on pelvic examination, severe localized pain

- Septic pelvic thrombophlebitis: Persistent fever despite antibiotic therapy, minimal abdominal findings

Figure 5: Clinical presentation of postpartum infections

Signs of Sepsis and Septic Shock:

| System | Clinical Manifestations |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular |

|

| Respiratory |

|

| Renal |

|

| Neurological |

|

| Gastrointestinal |

|

| Hematological |

|

| Metabolic |

|

Clinical Manifestations Based on Specific Site of Infection:

| Site of Infection | Specific Clinical Manifestations |

|---|---|

| Endometritis |

|

| Perineal wound infection |

|

| Cesarean section wound infection |

|

| Mastitis |

|

Clinical Alert: Rapidly progressing infections, particularly those involving Group A Streptococcus, can lead to toxic shock syndrome and have a fulminant course with rapid deterioration within hours. Look for signs such as severe pain, woody-hard edema, and rapidly spreading erythema.

6. Diagnosis and Assessment

6.1 Diagnostic Criteria

Key Concept: Early and accurate diagnosis of puerperal sepsis is essential for timely intervention and improved maternal outcomes.

WHO Diagnostic Criteria:

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), puerperal sepsis is diagnosed when infection of the genital tract occurs between rupture of membranes/labor and the 42nd day postpartum with two or more of the following:

- Pelvic pain

- Fever (oral temperature ≥38.5°C/101.3°F)

- Abnormal vaginal discharge (purulent, foul-smelling)

- Delay in the reduction of uterine size (subinvolution)

Sepsis Diagnosis (Updated Criteria):

For puerperal sepsis progressing to septic shock, the current diagnostic approach uses:

- Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score for ICU patients

- Quick SOFA (qSOFA) for non-ICU settings

qSOFA criteria (2 or more indicates higher risk):

- Respiratory rate ≥22 breaths/min

- Altered mental status (Glasgow Coma Scale <15)

- Systolic blood pressure ≤100 mmHg

Important Note: Remember that normal physiologic changes of pregnancy and postpartum may mask sepsis signs. Heart rate may be elevated by 10-20 beats/minute in normal pregnancy, and white blood cell counts are normally elevated in the postpartum period.

Assessment Tools:

Several assessment tools can help identify sepsis in obstetric patients:

- Modified Obstetric Early Warning Score (MOEWS)

- Maternal Early Warning Criteria (MEWC)

- Sepsis in Obstetrics Score (SOS)

6.2 Laboratory Findings

Initial Laboratory Studies:

| Test | Findings in Puerperal Sepsis | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Complete Blood Count (CBC) |

|

WBC count is normally elevated in postpartum period (15,000-30,000/mm³) |

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) | Elevated (>100 mg/L suggests severe infection) | Also elevated after uncomplicated delivery but to lesser extent |

| Procalcitonin | Elevated in bacterial infections (>0.5 ng/mL) | More specific marker than CRP |

| Lactate | Elevated (>2 mmol/L) in tissue hypoperfusion | Important prognostic marker in sepsis |

| Blood Cultures | Positive in bacteremia (15-30% of cases) | Collect before antibiotics if possible |

| Urinalysis/Urine Culture | May show evidence of UTI | To rule out urinary source of infection |

Additional Studies for Organ Dysfunction:

| Test | Abnormal Findings |

|---|---|

| Coagulation Studies |

|

| Renal Function Tests |

|

| Liver Function Tests |

|

| Arterial Blood Gas |

|

Microbiological Studies:

- Blood cultures: Collect before antibiotic administration

- Vaginal/cervical swabs: For culture and sensitivity

- Wound swabs: From perineal or abdominal incisions

- Lochia culture: Though often contaminated with normal flora

- Urine culture: To rule out urinary source

Imaging Studies:

- Transvaginal or abdominal ultrasound: To identify retained products of conception, endometrial thickening, fluid collections, or abscesses

- CT scan: For suspected abscess formation or pelvic thrombophlebitis

- MRI: Better soft tissue contrast; particularly useful for pelvic thrombophlebitis

- Chest X-ray: In cases of suspected pneumonia or ARDS

Nursing Tip: Remember the REEDA scale for assessing perineal or incision wounds in postpartum patients:

- R – Redness

- E – Edema

- E – Ecchymosis (bruising)

- D – Discharge

- A – Approximation (wound edges)

7. Treatment Approaches

7.1 Antibiotic Therapy

Key Concept: Early initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy is critical in puerperal sepsis management. Antibiotics should be started within one hour of recognition of sepsis.

Empiric Antibiotic Regimens:

Initial therapy should cover common pathogens, including aerobic and anaerobic bacteria:

| Severity | Recommended Regimen | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mild-Moderate Endometritis |

|

Classic regimen with best evidence |

| Severe infection or suspected resistant organisms |

|

Triple therapy for broader coverage |

| Alternative regimens |

|

Single-agent options with broad spectrum |

| Septic shock or life-threatening infection |

|

Maximum coverage for critically ill patients |

Clinical Alert: Antibiotic therapy should be tailored based on culture results as soon as they become available. Continue parenteral antibiotics until the patient is afebrile and asymptomatic for at least 48 hours.

Duration of Therapy:

- Continue parenteral antibiotics until 48 hours after clinical improvement (defervescence and reduced pain)

- Total duration typically 7-10 days depending on severity

- For uncomplicated cases: may switch to oral antibiotics after clinical improvement for outpatient completion

- For severe cases or with complications: longer courses may be needed

7.2 Fluid Management and Supportive Care

Fluid Resuscitation:

- Initial fluid bolus: 30 mL/kg of balanced crystalloid solution within the first 3 hours for patients with hypotension or elevated lactate

- Further fluid administration guided by hemodynamic assessment

- Target mean arterial pressure (MAP) ≥65 mmHg

- Monitor for signs of volume overload

Vasopressors:

- Indicated if hypotension persists despite adequate fluid resuscitation

- Norepinephrine is first-line agent (start at 0.05-0.1 mcg/kg/min, titrate as needed)

- Vasopressin may be added as a second agent

Additional Supportive Measures:

- Oxygen therapy: To maintain SpO₂ >94%

- Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: Unless contraindicated

- Glycemic control: Target blood glucose <180 mg/dL

- Stress ulcer prophylaxis: For patients with risk factors

- Nutritional support: Early initiation when possible

- Pain management: Appropriate analgesics based on pain severity

Monitoring Parameters:

- Vital signs: at least hourly in severe cases

- Urine output: goal >0.5 mL/kg/hour

- Serial lactate measurements to assess response to therapy

- Central venous pressure and ScvO₂ monitoring in severe cases

- Daily assessment of organ function (renal, hepatic, coagulation parameters)

7.3 Surgical Interventions

Indications for Surgical Intervention:

- Retained products of conception

- Abscess formation requiring drainage

- Necrotizing soft tissue infection

- Uterine necrosis or perforation

- Failure to respond to medical management

Potential Procedures:

| Procedure | Indications |

|---|---|

| Dilation and Curettage (D&C) | Removal of retained products of conception |

| Incision and Drainage | Abscess drainage, wound dehiscence management |

| Laparoscopy/Laparotomy | Peritonitis, suspected bowel injury, extensive abscess |

| Hysterectomy | Uterine necrosis, persistent infection despite medical therapy, life-threatening hemorrhage |

| Debridement | Necrotizing fasciitis, extensive wound infection |

Critical Point: In cases of suspected necrotizing fasciitis, urgent surgical consultation and aggressive debridement are essential. Delay in surgical intervention significantly increases mortality.

Special Considerations in Severe Cases:

- ICU admission criteria: Hypotension requiring vasopressors, respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, altered mental status, or multiple organ dysfunction

- Multidisciplinary approach: Obstetrics, infectious diseases, critical care, surgery, and nursing

- Transfer to tertiary care: Consider for cases requiring specialized care not available at current facility

8. Nursing Care Plan

8.1 Nursing Diagnosis

Key Concept: Comprehensive nursing care for puerperal sepsis focuses on infection control, pain management, nutritional support, patient education, and emotional support.

Priority Nursing Diagnoses:

- Risk for Infection (Progression/Spread)

- Acute Pain related to inflammatory process and tissue damage

- Hyperthermia related to infectious process

- Deficient Fluid Volume related to fever, decreased oral intake, and third spacing

- Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements related to increased metabolic demands and decreased intake

- Risk for Impaired Skin/Tissue Integrity at surgical/perineal sites

- Activity Intolerance related to inflammatory process and fatigue

- Anxiety related to illness and separation from newborn

- Risk for Ineffective Breastfeeding related to illness and possible separation

- Risk for Impaired Parent-Infant Attachment related to maternal illness and separation

8.2 Nursing Interventions

1. Infection Control and Management:

- Monitor vital signs: Temperature, pulse, respiration, blood pressure at least every 4 hours or more frequently if unstable

- Assess for signs of progressive infection: Worsening pain, spreading redness, increased drainage, systemic symptoms

- Perform comprehensive assessment: Use the REEDA scale to monitor wound healing

- Perform/assist with proper specimen collection: Blood cultures, wound swabs, urine samples

- Administer prescribed antibiotics: Ensure timely administration, monitor for effectiveness and adverse effects

- Practice and teach proper hand hygiene: Before and after all patient contact and procedures

- Maintain aseptic technique: During wound care, IV line management, catheter care

- Implement isolation precautions: As needed based on pathogen and institutional policy

- Monitor laboratory values: WBC count, CRP, procalcitonin, lactate

- Assess lochia: Amount, color, consistency, odor

- Assess uterine involution: Fundal height, firmness, tenderness

- Maintain strict intake and output monitoring: Ensure adequate hydration (at least 2000 ml/day)

- Position client in semi-Fowler’s position: To promote lochia drainage

2. Pain Management:

- Assess pain: Location, quality, intensity using a 0-10 scale, aggravating and relieving factors

- Administer prescribed analgesics: On schedule rather than PRN for severe pain

- Apply cold/warm compresses: To perineal area or incision site as appropriate

- Position for comfort: Support with pillows, assist with position changes

- Teach relaxation techniques: Deep breathing, guided imagery, distraction

- Monitor effectiveness of interventions: Reassess pain after interventions

3. Thermoregulation:

- Monitor temperature: At least every 4 hours or more frequently during febrile episodes

- Administer antipyretics: As prescribed

- Provide cooling measures: Light clothing, reduced room temperature, cool cloths

- Monitor for shaking chills: Provide warm blankets during chills, then remove when chills subside

- Encourage fluid intake: To replace losses from increased metabolic rate and diaphoresis

4. Fluid and Nutritional Management:

- Monitor hydration status: Skin turgor, mucous membranes, urine output, weight

- Administer IV fluids: As prescribed, monitor infusion rates and sites

- Encourage oral fluids: At least 2000-3000 ml/day if able to tolerate

- Provide high-protein, high-calorie diet: To support healing and immune function

- Encourage small, frequent meals: If patient has decreased appetite

- Monitor nutritional intake: Document food consumption, caloric count if needed

- Administer supplements: As prescribed (e.g., vitamins, iron)

- Consult dietitian: For individualized nutrition plan

5. Activity and Rest:

- Promote progressive activity: Based on tolerance and clinical condition

- Encourage early ambulation: To prevent complications of immobility

- Assist with activities of daily living: As needed

- Provide frequent rest periods: Between activities

- Implement venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: Early ambulation, sequential compression devices, anticoagulants as prescribed

6. Wound Care:

- Perform wound assessment: Using REEDA scale

- Maintain proper wound care: Clean with prescribed solution, apply dressings as ordered

- Teach perineal care: Proper cleansing technique, front-to-back wiping

- Encourage sitz baths: For perineal wounds, 2-3 times daily for 15-20 minutes

- Change peripads: Frequently to reduce bacterial growth

- Monitor wound drainage: Amount, color, consistency, odor

- Teach wound care: For discharge planning

7. Psychosocial Support:

- Assess emotional status: Fears, concerns, understanding of condition

- Provide emotional support: Therapeutic presence, active listening

- Facilitate mother-infant contact: When appropriate based on mother’s condition and infection control

- Support breastfeeding: Assist with breast pump if direct breastfeeding not possible

- Include family/support persons: In care and education

- Refer to social services: For additional support as needed

8. Patient and Family Education:

- Explain diagnosis and treatment: In clear, simple terms

- Teach medication administration: Purpose, dosage, schedule, side effects

- Instruct on signs of worsening infection: Increased pain, fever, redness, drainage

- Provide wound care instructions: Cleaning, dressing changes

- Discuss activity restrictions: Including pelvic rest (no tampons, douching, intercourse)

- Review follow-up care: Appointments, when to call healthcare provider

- Address breastfeeding concerns: Safety with antibiotics, maintaining milk supply

Nursing Tip: Document all assessments, interventions, and patient responses thoroughly. Use a systematic approach to ensure comprehensive care and early detection of complications.

9. Prevention Strategies

Evidence-Based Prevention of Puerperal Sepsis

Key Concept: Prevention strategies focus on risk reduction through proper infection control practices, antibiotic prophylaxis, and improved healthcare access.

Antenatal Prevention:

- Regular antenatal care: Identification and management of risk factors

- Screening and treatment: For urinary tract infections, bacterial vaginosis, Group B Streptococcus

- Nutritional support: To correct anemia and malnutrition

- Management of medical conditions: Diabetes, HIV, other immunocompromising conditions

- Education: Personal hygiene, recognition of warning signs

Intrapartum Prevention:

- Hand hygiene: Proper handwashing before all examinations and procedures

- Aseptic techniques: For all vaginal examinations and procedures

- Minimize vaginal examinations: Only when necessary and with sterile gloves

- Appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis: For cesarean delivery, Group B Streptococcus carriers, prolonged rupture of membranes

- Proper surgical technique: For cesarean delivery and episiotomy

Figure 6: Impact of Preventive Measures on Puerperal Sepsis Rates

WHO Recommendations for Antibiotic Prophylaxis:

| Procedure/Condition | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Cesarean Section |

|

| Manual Removal of Placenta | Single dose of first-generation cephalosporin or penicillin |

| Third or Fourth Degree Perineal Tear | Single dose of first-generation cephalosporin or penicillin |

| Operative Vaginal Delivery | Antibiotic prophylaxis recommended |

Postpartum Prevention:

- Early detection of complications: Regular vital sign monitoring, assessment of lochia and uterine involution

- Proper perineal care: Regular cleansing, frequent pad changes

- Early ambulation: To prevent thromboembolic complications

- Adequate nutrition and hydration: To support immune function and healing

- Education on warning signs: When to seek medical attention

- Proper wound care: For cesarean incision or episiotomy

Healthcare System Interventions:

- Implementation of standardized protocols: For prevention and early management

- Regular training of healthcare providers: On aseptic techniques and recognition of sepsis

- Adequate supplies: Of sterile equipment, gloves, antiseptic solutions

- Infection control committees: For monitoring and quality improvement

- Surveillance systems: For tracking maternal infections and outcomes

- Access to emergency obstetric care: For timely intervention when complications arise

Global Best Practice: The WHO’s Global Maternal and Neonatal Sepsis Initiative works to reduce the burden of maternal and neonatal infections worldwide through improved awareness, assessment, and quality of care. Key strategies include standardized identification and treatment protocols, enhanced surveillance, and targeted educational programs.

10. Mnemonics and Memory Aids

Learning Tools for Puerperal Sepsis

S.E.P.S.I.S

Mnemonic for Risk Factors of Puerperal Sepsis

S – Surgical interventions (cesarean section, instrumental delivery)

E – Exhaustion & prolonged labor

P – Premature rupture of membranes

S – Systemic conditions (anemia, diabetes, immunosuppression)

I – Invasive procedures (frequent vaginal exams, internal monitoring)

S – Sanitation issues (poor hygiene, unclean environment)

F.E.V.E.R

Assessment of Postpartum Fever Causes

F – Flu/Viral syndrome

E – Endometritis

V – Venous thrombosis/Thrombophlebitis

E – Episiotomy/wound infection

R – Retention of urine/Renal infection (UTI, pyelonephritis)

M.O.T.H.E.R

Nursing Interventions for Puerperal Sepsis

M – Monitor vital signs and symptoms

O – Obtain specimens for culture before antibiotics

T – Timely administration of antibiotics

H – Hydration and nutrition support

E – Educate about signs of worsening infection

R – Rest and position for comfort and drainage

P.U.E.R.P.E.R.A.L

Common Symptoms of Puerperal Sepsis

P – Pain (pelvic, abdominal)

U – Uterine subinvolution

E – Elevated temperature (>38°C)

R – Rapid pulse rate

P – Purulent discharge (foul lochia)

E – Extreme fatigue/malaise

R – Reduced appetite

A – Anxiety and distress

L – Leukocytosis (elevated white blood cells)

R.E.E.D.A

Wound Assessment Tool

R – Redness

E – Edema

E – Ecchymosis (bruising)

D – Discharge

A – Approximation (of wound edges)

11. Case Study

Clinical Application: Puerperal Sepsis Case

Patient: Maria, 28 years old, G2P2, day 3 postpartum after cesarean section due to failure to progress.

Presentation:

Maria has developed a fever of 38.7°C (101.6°F), tachycardia (heart rate 118 bpm), and is complaining of increasing pain at the incision site. She reports feeling generally unwell with chills and fatigue. On examination, the cesarean incision is erythematous with purulent discharge from the lower edge. Her uterus is tender on palpation with foul-smelling lochia. Maria is worried about caring for her newborn as she feels too weak.

Assessment Findings:

- Vital signs: Temperature 38.7°C, Heart rate 118 bpm, Respiratory rate 24/min, BP 110/70 mmHg

- Abdominal examination: Tender uterus, incision site with erythema, edema, and purulent discharge

- Lochia: Moderate amount, foul-smelling

- Laboratory: WBC 18,000/mm³ with left shift, CRP 12 mg/dL, Hemoglobin 9.8 g/dL

Nursing Diagnosis:

- Risk for Infection (Progression) related to cesarean wound infection and endometritis

- Acute Pain related to inflammatory process

- Hyperthermia related to infectious process

- Anxiety related to illness and concern about newborn care

- Risk for Ineffective Breastfeeding related to maternal illness

Interventions:

1. Immediate Actions:

- Notify healthcare provider of assessment findings

- Collect blood cultures, wound swab, and urine sample before starting antibiotics

- Begin monitoring vital signs every 4 hours

- Administer prescribed IV antibiotics promptly

- Start IV fluid therapy as ordered

2. Ongoing Nursing Care:

- Monitor temperature, vital signs, and incision site regularly

- Perform wound care per protocol, documenting wound appearance using REEDA

- Administer pain medication as prescribed and evaluate effectiveness

- Monitor intake and output, encourage adequate oral hydration

- Support breastfeeding as appropriate based on Maria’s condition

- Provide emotional support and reassurance

- Involve family members in baby care with close supervision

3. Patient Education:

- Explain the nature of the infection and treatment plan

- Instruct on the importance of completing the full course of antibiotics

- Teach signs of worsening infection that would require immediate attention

- Educate on wound care and hygiene practices

- Discuss strategies for balancing rest and newborn care

Outcome:

After 3 days of IV antibiotics (Clindamycin and Gentamicin), Maria’s temperature normalized and her pain decreased. The wound began healing with decreased erythema and discharge. Blood cultures were negative but wound cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus sensitive to the prescribed antibiotics. She was discharged on oral antibiotics to complete a 10-day course, with instructions for follow-up in 1 week and warning signs that would require immediate attention.

Case Learning Points:

- Early recognition and prompt intervention are critical in preventing progression of puerperal sepsis

- Multi-system approach to assessment helps identify complications early

- Balancing infection management with support for maternal-infant bonding is an important nursing consideration

- Comprehensive discharge teaching is essential to prevent recurrence or complications

12. References

- World Health Organization. (2015). WHO recommendations for prevention and treatment of maternal peripartum infections. WHO Press.

- Bonet, M., Souza, J. P., Abalos, E., Fawole, B., Knight, M., Kouanda, S., … & Gülmezoglu, A. M. (2017). The global maternal sepsis study and awareness campaign (GLOSS): study protocol. Reproductive health, 15(1), 1-17.

- Karsnitz, D. B. (2014). Puerperal infections of the genital tract: a clinical review. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 58(6), 632-642.

- Song, T., Yu, B., Chen, T., Dong, L., Wang, R., & Liu, X. (2019). Prevention and management of puerperal infection. Biomedical Research, 30(6), 982-985.

- Blackmon, M. M., Nguyen, H., & Mukherji, P. (2022). Postpartum Infection. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Brito, F. S., Ferreira, M. B. G., Palma, E., Narchi, N. Z., Pinto, L. F., & Souza, S. R. (2021). Factors associated with the presence, intensity, impact, and relief of perineal pain in women after normal birth. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 29, e3427.

- Wigati, P. W., & Sari, B. M. (2020). Nutritional status associated with the incidence of puerperal infection. Indonesian Journal of Nutrition and Dietetics, 8(1), 23-30.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG). (2017). Bacterial Sepsis following Pregnancy. Green-top Guideline No. 64b.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). (2019). ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 211: Critical Care in Pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 133(5), e303-e319.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. (2023). Diagnosis and Management of Maternal Sepsis. Consult Series #67.

- Acosta, C. D., Kurinczuk, J. J., Lucas, D. N., Tuffnell, D. J., Sellers, S., Knight, M., & United Kingdom Obstetric Surveillance System. (2014). Severe maternal sepsis in the UK, 2011–2012: a national case-control study. PLoS medicine, 11(7), e1001672.

- Bonet, M., Nogueira Pileggi, V., Rijken, M. J., Coomarasamy, A., Lissauer, D., Souza, J. P., & Gülmezoglu, A. M. (2017). Towards a consensus definition of maternal sepsis: results of a systematic review and expert consultation. Reproductive health, 14(1), 1-13.