Birth Asphyxia & Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy

Comprehensive Nursing Notes

Table of Contents

Introduction Definition & Epidemiology Pathophysiology Etiology Clinical Manifestations Sarnat Staging System Evaluation Nursing Assessment Nursing Care & Interventions Complications & Long-term Effects Prevention Strategies Helpful Mnemonics SummaryIntroduction

Birth asphyxia is a serious perinatal emergency that can lead to significant morbidity and mortality. It occurs in approximately 2 per 1000 live births in developed countries and up to 10 times higher in resource-limited settings. Untreated, birth asphyxia can result in hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), a type of brain injury that can have devastating lifelong consequences. As nurses, understanding the pathophysiology, recognizing the signs, and implementing appropriate interventions are crucial skills that directly impact newborn outcomes.

These comprehensive notes focus on birth asphyxia and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy to equip nursing professionals with the knowledge needed to provide evidence-based care. The content is structured to support both academic learning and clinical application, with visual aids and mnemonics to facilitate retention of key concepts.

Definition & Epidemiology

Definition

Birth asphyxia: A condition characterized by an impairment in gas exchange during the perinatal period, leading to hypoxemia (decreased PaO₂), hypercarbia (increased PaCO₂), and metabolic acidosis.

Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE): A type of brain injury that occurs when the brain doesn’t receive enough oxygen or blood flow during or shortly after birth, resulting in brain cell damage or death.

Epidemiology

- Incidence: 2 per 1000 live births in high-resource countries

- In resource-limited settings, incidence can be 10 times higher

- Mortality rate: 15-20% in the neonatal period

- Up to 25% of survivors develop permanent neurological deficits

- Accounts for approximately 23% of the 4 million neonatal deaths worldwide annually

Pathophysiology

Birth asphyxia causes a cascade of physiological events that lead to cellular damage. The hypoxic-ischemic injury occurs in two distinct phases: primary energy failure and secondary energy failure, separated by a latent period that presents a critical therapeutic window.

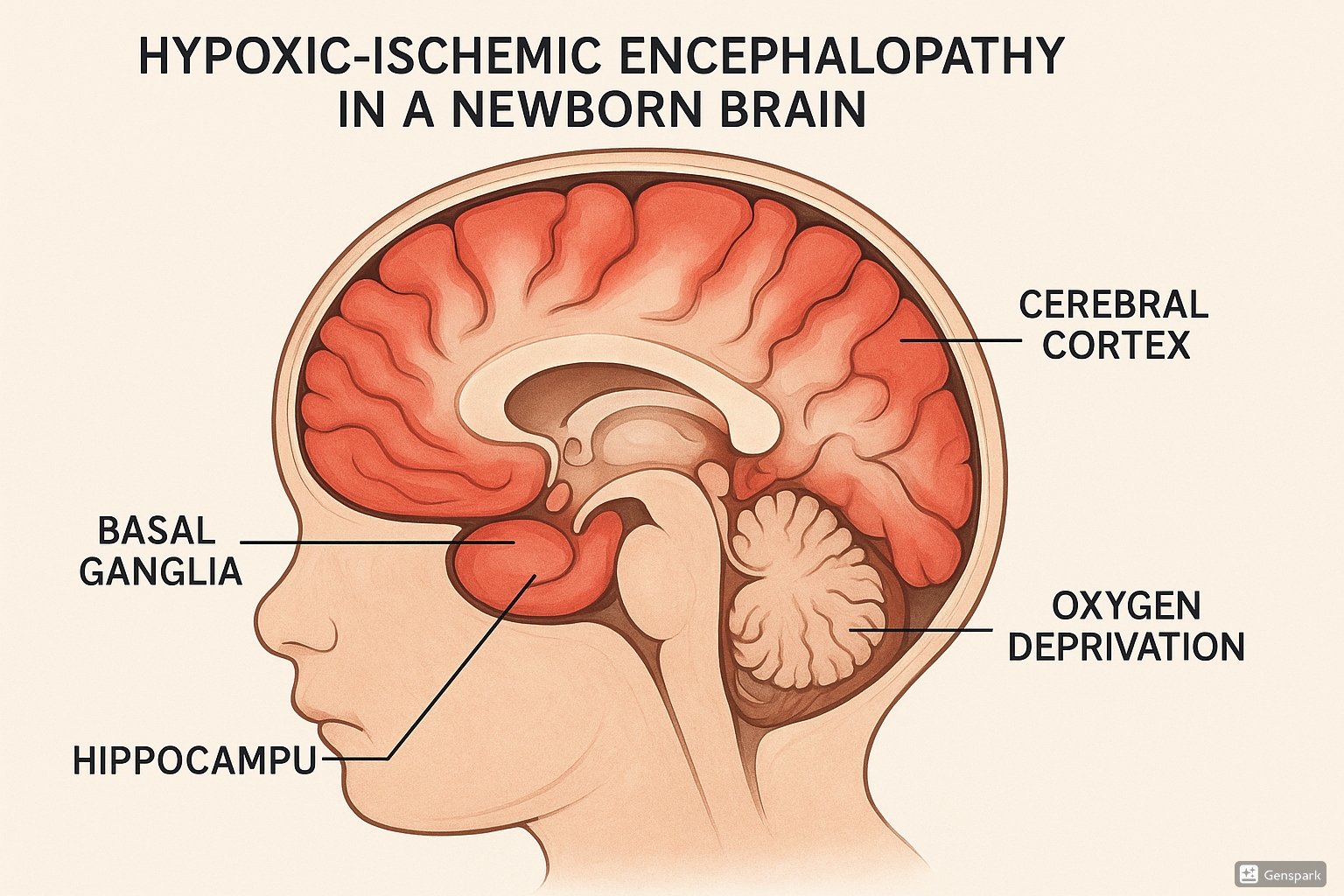

Figure 1: Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy in the newborn brain showing affected areas including the basal ganglia, hippocampus, and cerebral cortex.

Primary Energy Failure

Primary energy failure occurs immediately following the reduction in cerebral blood flow and oxygen delivery to the brain. This leads to:

- Decreased ATP production due to impaired oxidative phosphorylation

- Shift to anaerobic metabolism with resulting lactic acidosis

- Failure of ATP-dependent sodium-potassium pumps

- Excessive influx of sodium ions, causing neuronal depolarization

- Release of excitatory neurotransmitters, particularly glutamate

- Glutamate binding causes additional calcium and sodium influx

- Increased intracellular calcium leads to:

- Cerebral edema

- Microvascular damage

- Activation of cellular enzymes that damage cell structures

- Neuronal death via necrosis (immediate) or apoptosis (delayed)

Key Point: The severity of primary energy failure correlates with the extent of secondary energy failure that follows.

Latent Period

Following the restoration of blood flow after primary energy failure, there is a brief recovery period characterized by:

- Normalized cerebral metabolism

- Duration varies (usually 6-24 hours) depending on severity of initial insult

- Represents the optimal window for therapeutic interventions

Critical Insight: This latent period is the therapeutic window when interventions like hypothermia therapy are most effective.

Secondary Energy Failure

Secondary energy failure occurs 6-48 hours after the initial injury and is characterized by:

- Oxidative stress:

- Overproduction of free radicals

- Damage to neuronal cell membranes

- Particularly harmful to neonatal brains due to low antioxidant concentrations

- High concentration of unsaturated fatty acids forming additional free radicals

- Release of bound iron (Fe²⁺), which reacts with peroxides to form more free radicals

- Excitotoxicity:

- Excessive levels of glutamate overstimulate excitatory receptors

- Continued influx of sodium and calcium into neural cells

- Disruption of neuronal pathways for hearing, vision, sensory function

- Inflammation:

- Infiltration of neutrophils into cerebral tissue

- Release of inflammatory mediators by microglia

- Resulting cerebral edema

- White matter damage and scar tissue formation

Clinical Relevance: The ability to intervene during the latent phase before secondary energy failure begins is key to improving neurological outcomes.

Etiology

Birth asphyxia and subsequent HIE can result from multiple causes that compromise fetal oxygenation and perfusion. These causes can be categorized as maternal, uterine, placental, umbilical, and fetal factors.

| Category | Contributing Factors |

|---|---|

| Maternal Causes |

|

| Uterine Causes |

|

| Placental Causes |

|

| Umbilical Causes |

|

| Fetal Causes |

|

Mnemonic: “ASPHYXIA”

- A – Abruption of placenta

- S – Shoulder dystocia

- P – Prolonged labor

- H – Hypertension (maternal)

- Y – Young gestational age (prematurity)

- X – Xtra pressure on cord (compression)

- I – Infections (maternal)

- A – Abnormal presentations

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical presentation of birth asphyxia and HIE can vary depending on the severity and duration of the hypoxic-ischemic insult. Early recognition of these signs is crucial for prompt intervention.

Immediate Signs

- Poor response to resuscitative efforts

- Low Apgar scores (<7 at 5 minutes)

- Minimal or absent respiratory effort

- Hypotonia

- Abnormal fetal heart rate patterns

- Need for prolonged resuscitation

- Meconium-stained amniotic fluid

Laboratory Findings

- Metabolic acidosis (pH <7.0)

- Base deficit ≥12 mmol/L

- Hypoxemia (decreased PaO₂)

- Hypercarbia (increased PaCO₂)

- Elevated lactate levels

Neurological Signs

- Altered level of consciousness (lethargy, stupor, or coma)

- Abnormal tone (hypotonia or hypertonia)

- Seizures (within the first 24 hours)

- Abnormal reflexes

- Abnormal pupillary responses

- Abnormal eye movements

- Weak or absent suck reflex

Multi-Organ Involvement

- Cardiac: Hypotension, cardiogenic shock, tricuspid insufficiency, cardiac dysfunction

- Pulmonary: Respiratory distress, persistent pulmonary hypertension, meconium aspiration

- Renal: Acute tubular necrosis, oliguria or anuria, elevated creatinine

- Hepatic: Elevated liver enzymes, coagulation abnormalities

- Gastrointestinal: Feeding intolerance, necrotizing enterocolitis

- Hematologic: Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), thrombocytopenia

- Metabolic: Hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, hyponatremia

Critical Assessment: Remember that HIE is fundamentally a clinical diagnosis based on the constellation of findings in an infant with a history of perinatal asphyxia.

Sarnat Staging System

The modified Sarnat examination is used to determine the severity of encephalopathy and eligibility for therapeutic interventions. It classifies HIE into three stages based on clinical and neurological findings.

| Assessment Parameter | Stage 1 (Mild) | Stage 2 (Moderate) | Stage 3 (Severe) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level of Consciousness | Hyperalert | Lethargic | Stuporous/Comatose |

| Muscle Tone | Normal | Hypotonia | Flaccid |

| Posture | Normal | Distal flexion | Decerebrate |

| Reflexes | Exaggerated | Diminished | Absent |

| Moro Reflex | Strong | Weak | Absent |

| Suck Reflex | Weak or normal | Weak or absent | Absent |

| Autonomic Function | Sympathetic predominance | Parasympathetic predominance | Both systems depressed |

| Pupils | Mydriasis | Miosis | Variable, often unequal |

| Seizures | None | Common | Variable (may be absent due to severe brain injury) |

| EEG Findings | Normal | Low voltage, theta and delta waves | Burst suppression or isoelectric |

| Duration | <24 hours | 2-14 days | Hours to weeks |

| Prognosis | Good | Guarded | Poor |

Clinical Application: For therapeutic hypothermia eligibility, an infant must demonstrate abnormalities in at least 3 categories to be considered to have encephalopathy. If there is a tie between categories, the level of consciousness serves as the “tiebreaker.”

Important Note: The Sarnat staging system is validated for term or near-term infants (≥35 weeks gestation) and may not be applicable to significantly preterm infants.

Evaluation

Proper evaluation of an infant with suspected birth asphyxia and HIE involves multiple assessment modalities to determine severity and guide appropriate interventions.

Initial Assessment

- Detailed perinatal history to identify risk factors

- Apgar scores at 1, 5, and 10 minutes

- Physical examination with focus on neurological status

- Assessment using the modified Sarnat criteria

Laboratory Studies

- Arterial blood gas analysis (assess degree of acidosis)

- Complete blood count (to detect infection or anemia)

- Serum electrolytes

- Blood glucose monitoring

- Liver function tests (AST, ALT)

- Kidney function tests (BUN, creatinine)

- Coagulation studies

- Cardiac enzymes (troponin, CK-MB)

Neurological Assessment

- Electroencephalogram (EEG) or amplitude-integrated EEG (aEEG) to detect seizure activity and assess background brain activity

- Video EEG monitoring for suspected clinical seizures

- Neuroimaging:

- Cranial ultrasound: Initial screening but limited sensitivity for HIE

- MRI: Gold standard, typically performed 5-10 days post-event to evaluate extent of injury and pattern (watershed vs. deep nuclear)

- CT scan: May be used in acute settings but less preferred due to radiation exposure

Other Diagnostic Tests

- Echocardiography to assess cardiac function

- Renal ultrasound if renal involvement is suspected

- Placental pathology examination

Mnemonic: “EVALUATE HIE”

- E – Encephalogram (EEG for seizure monitoring)

- V – Vital signs assessment

- A – Arterial blood gas

- L – Laboratory tests (CBC, electrolytes, glucose)

- U – Ultrasound (cranial, cardiac)

- A – Apgar score review

- T – Tone and reflexes assessment

- E – Electrolyte monitoring

- H – History (perinatal)

- I – Imaging (MRI preferred)

- E – Examination using Sarnat criteria

Nursing Assessment

Comprehensive nursing assessment is essential for early detection of birth asphyxia and ongoing monitoring of the infant with HIE. Systematic and thorough assessment allows for prompt intervention and prevention of complications.

Initial Nursing Assessment

- Respiratory assessment:

- Respiratory rate, pattern, and effort

- Presence of retractions, grunting, nasal flaring

- Oxygen saturation monitoring

- Breath sounds

- Cardiovascular assessment:

- Heart rate and rhythm

- Blood pressure

- Peripheral perfusion

- Capillary refill time

- Neurological assessment:

- Level of consciousness

- Muscle tone and posture

- Primitive reflexes (Moro, suck, grasp)

- Pupillary responses

- Presence of seizures or abnormal movements

- Thermoregulation:

- Core and peripheral temperature

- Temperature stability

Ongoing Monitoring

- Fluid balance:

- Intake and output measurement

- Specific gravity of urine

- Presence of proteinuria or hematuria

- Evidence of renal dysfunction

- Gastrointestinal system:

- Abdominal distension

- Bowel sounds

- Presence of blood in stools (sign of NEC)

- Feeding tolerance

- Metabolic status:

- Blood glucose monitoring

- Electrolyte levels

- Signs of hypoglycemia or hypocalcemia

- Seizure monitoring:

- Clinical signs: subtle mouth movements, eye deviation, apnea, tonic posturing

- EEG or aEEG findings

- Response to anticonvulsant therapy

Documentation Tip: Use a systematic approach to document assessments, interventions, and the infant’s response. This creates a comprehensive record that facilitates continuity of care and early detection of changing status.

Nursing Care & Interventions

The nursing care of infants with birth asphyxia and HIE is multifaceted, focusing on supporting physiologic functions, preventing complications, and facilitating therapeutic interventions. Evidence-based nursing care is essential for optimizing outcomes.

Immediate Interventions

- Establish and maintain airway:

- Position the infant to optimize airway

- Clear secretions as needed

- Assist with intubation if required

- Support respiratory function:

- Provide supplemental oxygen as needed

- Assist with mechanical ventilation

- Monitor oxygen saturation continuously

- Prevent hyperoxia which can increase free radical production

- Maintain cardiovascular stability:

- Monitor heart rate and blood pressure

- Administer fluids and vasopressors as prescribed

- Ensure adequate perfusion

- Thermoregulation:

- Prevent hyperthermia which can worsen neurological injury

- For infants not receiving therapeutic hypothermia, maintain normothermia

- Use radiant warmers or incubators as appropriate

- Neurological monitoring:

- Perform regular neurological assessments

- Implement seizure precautions

- Document and report changes promptly

Therapeutic Hypothermia

Therapeutic hypothermia is the standard of care for moderate to severe HIE in infants ≥35 weeks gestation. It must be initiated within 6 hours of birth to be effective.

- Preparation:

- Ensure cooling equipment is ready and functioning

- Place temperature probes (rectal/esophageal for core temperature and skin for surface temperature)

- Establish IV access and organize monitoring equipment

- Implementation:

- Selective head cooling or whole-body cooling to target temperature (33-34°C for whole-body cooling)

- Continuously monitor core temperature

- Maintain cooling for 72 hours

- Monitor for complications related to hypothermia

- Key nursing considerations:

- Maintain skin integrity with frequent repositioning and skin assessment

- Monitor for coagulopathy (increased risk of bleeding)

- Observe for bradycardia (expected during cooling)

- Assess for shivering and administer sedation as prescribed

- Monitor for fluid and electrolyte imbalances

- Rewarming phase:

- Rewarm slowly at 0.5°C/hour to prevent complications

- Monitor closely for seizures during rewarming

- Assess for hypotension which may occur during rewarming

- Continue neurological monitoring

Safety Alert: During therapeutic hypothermia, avoid hyperthermia at all costs as it can significantly worsen neurological outcomes. Ensure continuous temperature monitoring with backup systems in place.

Ongoing Care

- Respiratory care:

- Suction airway as needed, maintaining a patent airway

- Position to optimize oxygenation

- Monitor ventilator settings if intubated

- Prevent hypocarbia which can worsen cerebral blood flow

- Fluid and electrolyte management:

- Strict intake and output monitoring

- Administer IV fluids as prescribed, being cautious with volume in case of renal dysfunction

- Monitor serum electrolytes and correct imbalances

- Monitor renal function

- Nutritional support:

- Coordinate with the healthcare team regarding feeding initiation

- Assess feeding readiness and tolerance

- Support enteral or parenteral nutrition as prescribed

- Neurological care:

- Administer anticonvulsants as prescribed

- Position to prevent increased intracranial pressure

- Minimize environmental stimuli

- Monitor for signs of increased intracranial pressure

- Medication administration:

- Antibiotics if infection is suspected

- Anticonvulsants for seizure control

- Analgesics and sedatives as needed

- Vasopressors for blood pressure support

- Family support:

- Provide education about HIE and expected course

- Involve parents in care when appropriate

- Offer emotional support and counseling resources

- Prepare for potential long-term care needs

Mnemonic: “CARE for HIE”

- C – Control seizures and monitor for their occurrence

- A – Airway management and adequate ventilation

- R – Regulate temperature (therapeutic hypothermia or normothermia)

- E – Ensure adequate perfusion and nutrition

- H – Handle minimally and create a neuroprotective environment

- I – Involve parents and provide education

- E – Evaluate and document neurological status frequently

Complications & Long-term Effects

Birth asphyxia and HIE can lead to significant short-term complications and long-term sequelae that affect multiple organ systems. Understanding these potential outcomes is essential for planning care and counseling families.

Short-term Complications

- Neurological:

- Seizures (40-60% of infants with moderate to severe HIE)

- Cerebral edema

- Increased intracranial pressure

- Respiratory:

- Persistent pulmonary hypertension

- Respiratory failure

- Meconium aspiration syndrome

- Cardiovascular:

- Myocardial dysfunction

- Hypotension

- Cardiogenic shock

- Renal:

- Acute kidney injury

- Acute tubular necrosis

- SIADH (syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone)

- Gastrointestinal:

- Necrotizing enterocolitis

- Feeding intolerance

- Hepatic dysfunction

- Metabolic:

- Hypoglycemia

- Hypocalcemia

- Metabolic acidosis

- Hematologic:

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Thrombocytopenia

- Bleeding complications

Long-term Sequelae

The long-term outcomes depend significantly on the severity of HIE, with mortality approaching 30% for severe cases. Among survivors:

- Neurological:

- Cerebral palsy (most common long-term complication)

- Epilepsy/seizure disorders (15-30% of survivors)

- Cognitive impairment or intellectual disability

- Microcephaly

- Sensory impairments:

- Visual impairment or blindness

- Hearing impairment or deafness

- Developmental:

- Motor delays

- Language and speech delays

- Learning disabilities

- Attention deficits and hyperactivity

- Behavioral:

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Behavior problems

- Emotional regulation difficulties

- Other:

- Feeding difficulties

- Growth problems

- Recurrent aspiration

| HIE Severity | Mortality Rate | Neurological Sequelae in Survivors |

|---|---|---|

| Mild (Sarnat Stage I) | 0-2% | 0-5% |

| Moderate (Sarnat Stage II) | 10-15% | 20-40% |

| Severe (Sarnat Stage III) | 50-75% | 80-100% |

Prognostic Factors

Several factors can help predict outcomes in infants with HIE:

- Severity of encephalopathy (Sarnat stage)

- Duration of asphyxia

- Timing of therapeutic intervention

- Presence and severity of seizures

- EEG findings

- MRI findings and pattern of injury

- Need for prolonged ventilation

- Multiorgan involvement

Important: Early developmental intervention and follow-up are crucial for infants with HIE. Nurses play a vital role in educating parents about the importance of follow-up appointments, therapy services, and developmental monitoring.

Prevention Strategies

Prevention of birth asphyxia and HIE focuses on identifying risk factors, appropriate antenatal care, and prompt intervention during labor and delivery.

Antepartum Prevention

- Early identification of high-risk pregnancies

- Regular antenatal care and monitoring

- Management of maternal conditions that increase risk (hypertension, diabetes, etc.)

- Ultrasonography to detect fetal anomalies and growth restriction

- Maternal education about warning signs requiring immediate attention

Intrapartum Prevention

- Continuous electronic fetal monitoring for high-risk pregnancies

- Proper interpretation of fetal heart rate patterns

- Prompt intervention for non-reassuring fetal status

- Appropriate timing of cesarean sections when indicated

- Skilled birth attendants trained in neonatal resuscitation

- Availability of emergency obstetric services

Immediate Postnatal Prevention

- Skilled personnel present at all deliveries

- Prompt initiation of resuscitation when needed

- Following standardized neonatal resuscitation protocols

- The “Golden Minute” approach: focusing on essential interventions within the first minute after birth

- Drying

- Providing warmth

- Clearing the airway

- Stimulation to breathe

- Bag-mask ventilation if necessary

- Early recognition of signs of encephalopathy to facilitate timely intervention

Nursing Roles in Prevention

- Patient education about risk factors and warning signs

- Skilled assessment during labor to identify concerning patterns

- Prompt communication with the healthcare team about concerning findings

- Maintaining competency in neonatal resuscitation

- Participating in simulation trainings for emergency scenarios

- Advocating for appropriate monitoring and interventions

Critical Insight: Early recognition and prompt intervention are key to preventing progression from birth asphyxia to severe HIE. The 6-hour window for initiating therapeutic hypothermia highlights the importance of rapid assessment and response.

Helpful Mnemonics

Mnemonics can aid in remembering key concepts related to birth asphyxia and HIE. Here are several useful memory aids for nursing students:

“BIRTH ASPHYXIA” – Risk Factors Assessment

- B – Breech presentation

- I – Infections (maternal)

- R – Rupture of uterus

- T – Trauma during delivery

- H – Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

- A – Abruptio placenta

- S – Shoulder dystocia

- P – Prolonged labor

- H – Hyperstimulation of uterus

- Y – Young maternal age (extreme)

- X – Xtreme prematurity

- I – Irregular fetal heartbeat

- A – Anemia (maternal)

“HYPOXIC” – Clinical Signs of HIE

- H – Hypotonia or hypertonia

- Y – Yawning or sighing abnormal respirations

- P – Poor feeding or absent suck reflex

- O – Obtunded consciousness

- X – Xtra irritability or lethargy

- I – Irregular posturing

- C – Convulsions or seizures

“COOL” – Therapeutic Hypothermia Management

- C – Check eligibility criteria (moderate-severe HIE, ≥35 weeks)

- O – Onset within 6 hours of birth

- O – Obtain target temperature (33-34°C)

- L – Length of therapy: 72 hours followed by slow rewarming

“MONITOR” – Ongoing Assessment of HIE

- M – Mental status and neurological signs

- O – Oxygenation and ventilation

- N – Nutrition and feeding ability

- I – Intake and output

- T – Temperature (core and peripheral)

- O – Organ function (renal, hepatic, cardiac)

- R – Reflexes and response to stimulation

“SARNAT” – Remembering Key Elements of Staging

- S – State of consciousness

- A – Activity and tone

- R – Reflexes (primitive)

- N – Neuromuscular control

- A – Autonomic function

- T – Tendency for seizures

Summary

Birth asphyxia and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy represent significant challenges in neonatal care that require prompt recognition and intervention. Understanding the pathophysiological processes of primary and secondary energy failure provides the foundation for implementing effective therapeutic strategies.

Nurses play a pivotal role in the prevention, early identification, and management of infants with HIE. Skilled assessment using the Sarnat staging system, implementation of therapeutic hypothermia within the critical 6-hour window, and ongoing monitoring for complications are essential nursing responsibilities that directly impact outcomes.

The nursing care of infants with HIE requires a multisystem approach addressing neurological, respiratory, cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic needs. Family education and support are equally important components of comprehensive care, particularly given the potential for long-term sequelae.

With advances in neonatal care, particularly therapeutic hypothermia, outcomes for infants with moderate HIE have improved significantly. However, continuous education, skillful assessment, and evidence-based interventions remain critical to further reducing morbidity and mortality associated with birth asphyxia and HIE.

Remember that every intervention during the acute period has the potential to influence long-term developmental outcomes. The nurse’s knowledge, vigilance, and advocacy are powerful tools in improving the trajectory for these vulnerable infants.

Global Best Practices

Around the world, various innovative approaches have been developed to address birth asphyxia and HIE. These global best practices offer valuable insights for nursing care:

- Helping Babies Breathe (HBB) Initiative: Developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics, this evidence-based educational program has been implemented in resource-limited settings worldwide. It focuses on the “Golden Minute” after birth, emphasizing basic neonatal resuscitation skills that can be performed by any birth attendant.

- Low-cost cooling technologies: Countries with limited resources have developed phase-change material cooling devices and passive cooling methods to provide therapeutic hypothermia in settings without advanced cooling equipment.

- Telemedicine support: Remote consultation systems connect community hospitals with tertiary centers to guide management of HIE, particularly decisions regarding therapeutic hypothermia and transfer.

- Family-integrated care models: Developed in Canada and implemented globally, these models incorporate parents as primary caregivers from an early stage, improving developmental outcomes particularly for infants requiring long-term care.

- Neurodevelopmental follow-up protocols: Structured, standardized follow-up programs developed in Sweden and the UK provide comprehensive developmental assessment and early intervention for infants affected by HIE.

- Neuroprotective care bundles: Implemented in Australia and New Zealand, these bundles combine minimal handling, pain management, positioning, and environmental modifications to create a neuroprotective environment for vulnerable infants.