Abdominal Wall Defects in Children

Comprehensive Nursing Notes

Clinical Focus

Abdominal wall defects are congenital abnormalities where organs protrude through an opening in the abdomen. Early recognition, appropriate management, and interdisciplinary care are essential for optimal outcomes in affected neonates.

Introduction to Abdominal Wall Defects

Abdominal wall defects are congenital malformations characterized by abnormal development of the anterior abdominal wall, resulting in herniation or exposure of intra-abdominal organs. These conditions typically develop during embryogenesis and require prompt medical and surgical intervention after birth.

Mind Map: Overview of Abdominal Wall Defects

Abdominal wall defects vary in severity and complexity, ranging from isolated defects to those associated with multiple anomalies. Understanding their embryological development, clinical presentations, and management strategies is essential for providing optimal care to affected infants.

Classification and Comparison

| Defect | Incidence | Defect Location | Covering Sac | Associated Anomalies | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

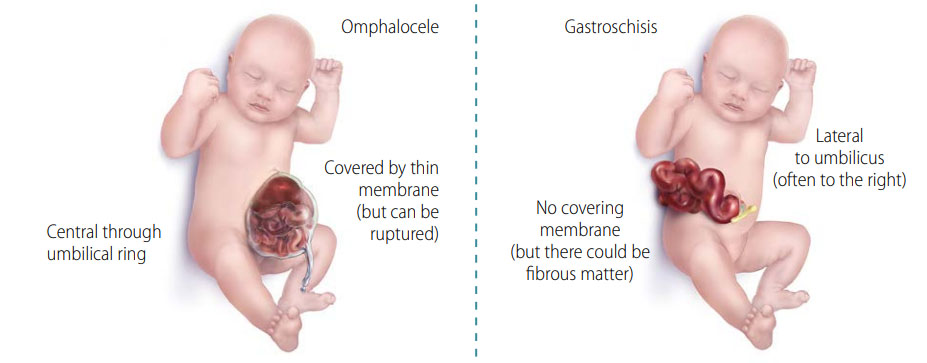

| Gastroschisis | 1:2,000 births | Right of umbilicus | No | Rare (10-15%); mostly intestinal atresia | Exposed bowel, inflamed/edematous intestines |

| Omphalocele | 1:4,200 births | At umbilicus | Yes (peritoneum) | Common (50-70%); cardiac, chromosomal, Beckwith-Wiedemann | Variable size, umbilical cord inserts into sac |

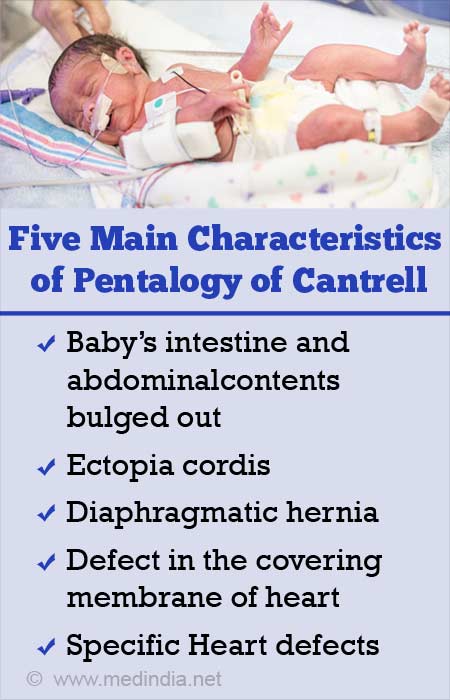

| Pentalogy of Cantrell | 1:65,000 births | Midline/epigastric | Variable | Defines syndrome: cardiac, diaphragmatic, sternal, pericardial defects | Spectrum of severity; may include ectopia cordis |

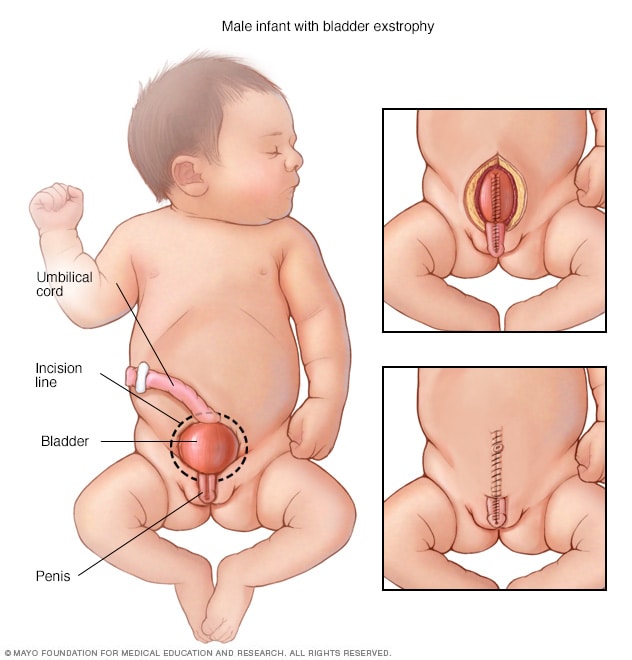

| Bladder Exstrophy | 1:50,000 births | Lower abdomen | No | Epispadias, VUR, pubic diastasis | Exposed bladder mucosa, urine dripping |

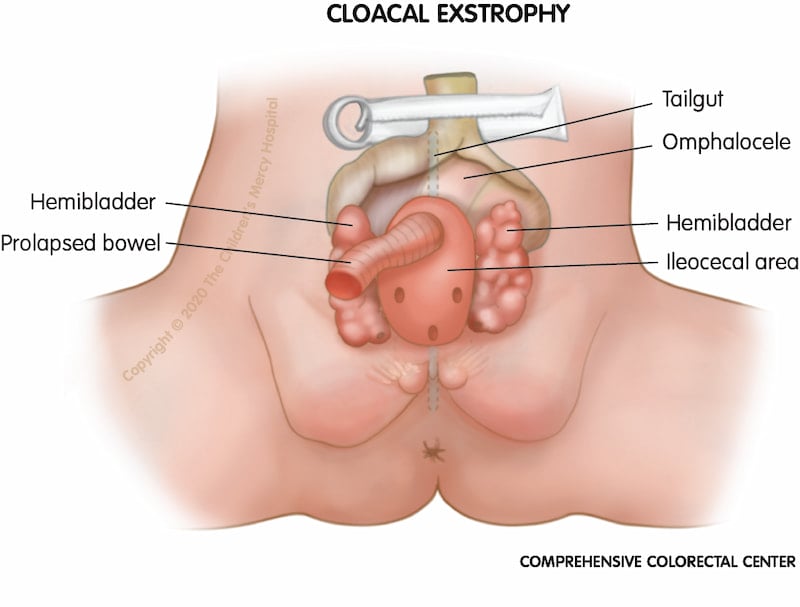

| Cloacal Exstrophy | 1:200,000 births | Lower abdomen | No | Very common: spinal, GI, GU, orthopedic | Exposed bladder halves, cecal plate, omphalocele |

Mnemonic: “GASP-C”

Remember the main abdominal wall defects:

- Gastroschisis: Got no sac, right-sided defect

- At the umbilicus: All omphaloceles are central

- Sac present: Sac covers omphalocele, not gastroschisis

- Pentalogy: Pentad of defects (5 abnormalities)

- Cloacal/bladder: Caudal abdominal wall defects

Gastroschisis

Definition & Pathophysiology

Gastroschisis is a congenital abdominal wall defect characterized by evisceration of intestines (and occasionally other abdominal organs) through a full-thickness paraumbilical defect, typically located to the right of the umbilical cord. Unlike omphalocele, the herniated organs lack a protective membrane covering.

Embryology:

The exact pathogenesis remains unclear, but gastroschisis is believed to result from:

- Disruption of the right omphalomesenteric artery leading to weakness in the abdominal wall

- Abnormal involution of the right umbilical vein

- Rupture of the amniotic membrane at the base of the umbilical cord

Risk Factors:

- Young maternal age (<20 years)

- Low socioeconomic status

- Maternal smoking, alcohol, or recreational drug use

- Poor maternal nutrition

- Vasoactive medication exposure during pregnancy

Clinical Pearl

Unlike omphalocele, gastroschisis typically occurs as an isolated defect without associated chromosomal abnormalities, making prognosis generally favorable if managed appropriately.

Clinical Features

- Prenatal: Elevated maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (MSAFP), free-floating intestinal loops on ultrasound

- At birth: Visible intestines protruding through abdominal wall defect to the right of intact umbilical cord

- Bowel appearance: Typically edematous, thickened, matted, and inflamed due to exposure to amniotic fluid

- Associated findings: Intestinal atresia (10-15%), malrotation, volvulus, or perforation

- Physiologic compromise: Fluid loss, hypothermia, sepsis risk, electrolyte imbalances

Complex vs. Simple Gastroschisis:

| Simple (85-90%) | Complex (10-15%) |

|---|---|

| Intestinal evisceration only | Associated with intestinal atresia, perforation, necrosis, or volvulus |

| Better prognosis | Higher morbidity and mortality |

| Shorter hospital stay | Prolonged TPN, longer to reach full feeds |

Diagnosis & Assessment

Prenatal:

- Elevated maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (MSAFP)

- Ultrasound findings:

- Free-floating intestinal loops outside the abdomen

- Defect to the right of normally inserted umbilical cord

- No membrane covering the eviscerated organs

- Serial ultrasounds to monitor for bowel dilation, wall thickening

Postnatal:

- Clinical appearance is diagnostic

- Assess for:

- Bowel viability, color, and perfusion

- Signs of intestinal atresia or other complications

- Size of abdominal wall defect

- Physiologic stability (temperature, fluid status)

- Laboratory evaluation: CBC, electrolytes, blood gas, glucose

Management

Immediate Postnatal Care:

- Cover exposed bowel with sterile, warm, moist, non-adherent dressing

- Place infant in lateral position to prevent kinking of mesenteric vessels

- Insert orogastric tube for decompression

- Maintain thermal regulation

- Fluid resuscitation with isotonic fluids (10-20 mL/kg bolus initially)

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics

- Minimal handling of eviscerated organs

Surgical Management:

Depends on the size of the defect and condition of the bowel:

- Primary closure: If defect is small and abdominal cavity can accommodate bowel without excessive pressure

- Staged reduction:

- Silo placement (preformed or custom) for gradual reduction

- Daily reduction of contents over 5-10 days

- Final closure when sufficient reduction achieved

Nursing Considerations:

- Monitoring for abdominal compartment syndrome:

- Respiratory distress

- Lower extremity edema or cyanosis

- Decreased urine output

- Maintaining bowel integrity:

- Assess color, blood flow, signs of necrosis

- Keep bowel moist and protected

- Nutritional support:

- NPO status initially

- Total parenteral nutrition (TPN)

- Slow advancement of feeds when bowel function returns

- Pain management

- Infection prevention

- Family support and education

Long-term Complications:

- Short bowel syndrome

- Parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease

- Feeding intolerance

- Growth delay

- Adhesive small bowel obstruction

- Incisional hernia

Prognosis

Overall survival rate for gastroschisis is >90%. Simple gastroschisis has excellent outcomes, with most children achieving normal growth and development. Complex gastroschisis has higher morbidity, with longer hospital stays and higher risk of long-term complications.

Omphalocele

Definition & Pathophysiology

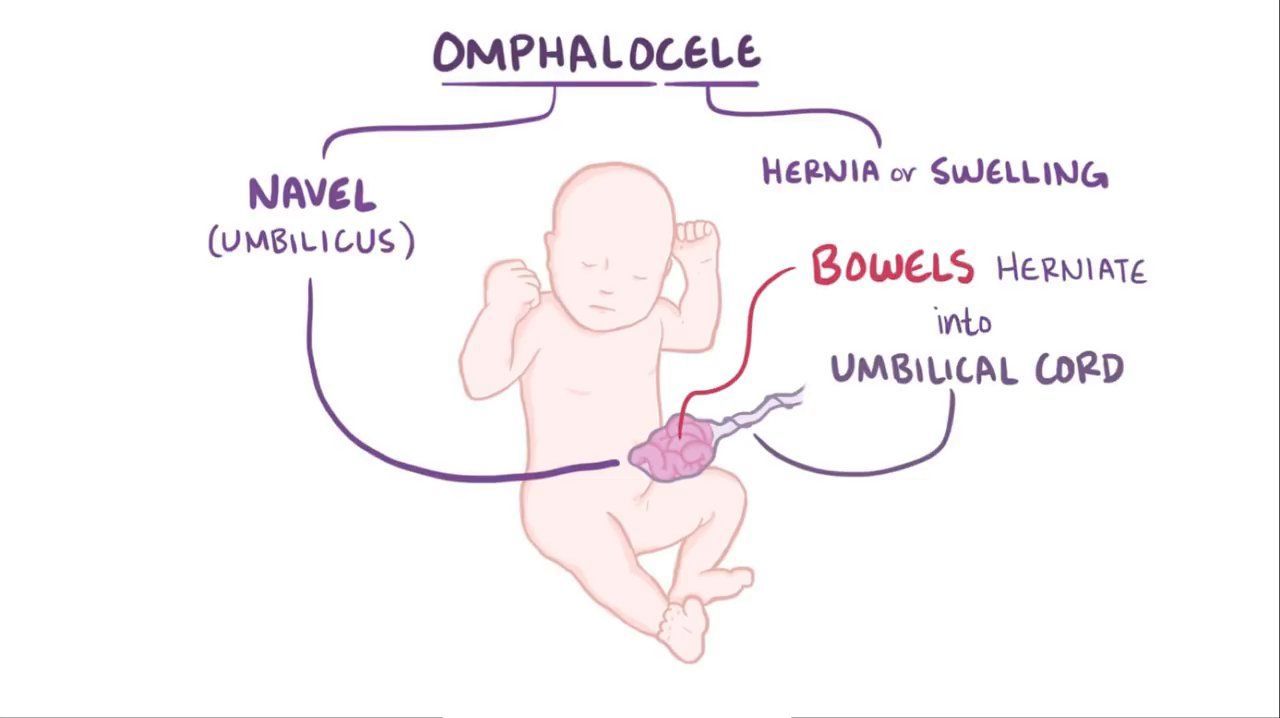

Omphalocele is a congenital abdominal wall defect where abdominal contents herniate through the umbilical ring and are covered by a membranous sac consisting of peritoneum, Wharton’s jelly, and amnion. The umbilical cord inserts directly into the sac rather than into the abdominal wall.

Embryology:

Omphalocele results from failure of the midgut to return to the abdominal cavity during the 10th-12th week of gestation after physiologic herniation. Normal embryologic development includes:

- Physiologic midgut herniation into umbilical cord (weeks 6-10)

- Return of intestines to abdominal cavity (weeks 10-12)

- Closure of the umbilical ring

Failure of intestines to return and/or umbilical ring to close properly results in omphalocele.

Classification:

- Small: <2 cm, containing only intestine

- Medium: 2-5 cm

- Giant/Large: >5 cm, often containing liver and other organs

Mnemonic: “SAME-O”

Omphalocele associations:

- Syndromes (Beckwith-Wiedemann)

- Anomalies (multiple)

- Membrane covered

- Extensive testing needed

- Omphalocele at umbilicus

Associated Conditions

Unlike gastroschisis, omphalocele is frequently associated with other congenital anomalies (50-70% of cases):

Syndromes:

- Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome: Macroglossia, gigantism, hypoglycemia

- Pentalogy of Cantrell: Omphalocele with sternal, diaphragmatic, pericardial, and cardiac defects

- OEIS Complex: Omphalocele, exstrophy, imperforate anus, spinal defects

- Trisomy syndromes: Trisomy 13, 18, 21

Chromosomal Abnormalities:

- Present in 30-40% of cases

- Most common: Trisomy 18, Trisomy 13

Organ System Anomalies:

- Cardiac: VSD, ASD, tetralogy of Fallot (30-50%)

- Gastrointestinal: Malrotation, intestinal atresia

- Genitourinary: Bladder/cloacal exstrophy, renal anomalies

- Musculoskeletal: Limb abnormalities, scoliosis

- Neural tube defects: Spina bifida, anencephaly

Clinical Features & Diagnosis

Prenatal:

- Elevated maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (MSAFP)

- Ultrasound findings:

- Midline abdominal mass with membrane covering

- Umbilical cord insertion into the sac

- Herniated organs (intestine, liver) visible within sac

- Further testing frequently indicated:

- Amniocentesis for karyotype

- Fetal echocardiogram

- Detailed anatomy scan

Postnatal:

- Visual inspection is diagnostic

- Transparent sac containing abdominal contents

- Umbilical cord inserts into sac’s apex

- Variable size from small to giant

Management

Immediate Care:

- Protect the sac with moist, sterile dressing

- Maintain temperature regulation

- Place nasogastric tube for decompression

- Secure IV access for fluid management

- Prophylactic antibiotics

- Thorough assessment for associated anomalies

- Respiratory support if needed (especially for giant omphaloceles)

Surgical Approaches:

- Primary closure: For small to medium defects with adequate abdominal cavity

- Staged reduction: Using silo for gradual visceral reduction

- Delayed surgical repair: For giant omphaloceles

- Non-operative management with topical agents (silver sulfadiazine, povidone-iodine)

- Allows epithelialization of sac

- Ventral hernia repair at 1-2 years of age

Nursing Considerations

- Maintain sac integrity:

- Monitor for signs of rupture or infection

- Gentle handling during care

- Position to avoid pressure on sac

- Respiratory management:

- Monitor for pulmonary hypoplasia, especially with giant omphaloceles

- Assess work of breathing and oxygen requirements

- Nutritional support:

- TPN until enteral feeds tolerated

- Slow feeding advancement

- Developmental care and positioning

- Family support and education

- Care coordination for multiple subspecialties

Prognosis & Complications

Prognosis varies widely depending on:

- Size of the defect

- Presence and severity of associated anomalies

- Chromosomal abnormalities

Survival Rates:

- Isolated omphalocele: >90%

- With associated anomalies: 70-80%

- With chromosomal abnormalities: 30-60%

Long-term Complications:

- Pulmonary issues:

- Chronic lung disease

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Recurrent respiratory infections

- Gastrointestinal:

- Gastroesophageal reflux

- Feeding difficulties

- Malabsorption

- Abdominal wall issues:

- Ventral hernia

- Cosmetic concerns

- Growth and developmental delays

Other Abdominal Wall Defects

Pentalogy of Cantrell

Pentalogy of Cantrell is a rare congenital disorder characterized by a specific combination of five defects affecting the midline structures of the thorax and abdomen.

The Five Classical Defects:

- Midline supraumbilical abdominal wall defect (often omphalocele)

- Defect of the lower sternum

- Deficiency of the anterior diaphragm

- Defect in the diaphragmatic pericardium

- Congenital intracardiac abnormalities

Mnemonic: “CANTRELL”

Remember the five defects of Pentalogy of Cantrell:

- Cardiac defects

- Abdominal wall defect (omphalocele)

- Notch in lower sternum

- Thoracic diaphragm defect (anterior)

- Rift in pericardium

- Ectopia cordis (in severe cases)

- LLethal without intervention

Clinical Features:

- Variable presentation based on severity of defects

- Omphalocele (often containing liver)

- Sternal cleft or bifid sternum

- Ectopia cordis in severe cases (heart positioned outside thoracic cavity)

- Respiratory distress

- Cyanosis due to cardiac defects

Diagnosis:

- Prenatal ultrasound may detect:

- Omphalocele

- Sternal defect

- Ectopia cordis

- Cardiac defects

- Postnatal evaluation:

- Physical examination

- Echocardiography

- CT scan or MRI

- Genetic testing

Management:

- Requires multidisciplinary approach

- Immediate stabilization:

- Protection of exposed organs

- Respiratory support

- Cardiovascular stabilization

- Surgical repair:

- Complex, multistage procedures

- Repair of omphalocele

- Sternum and diaphragm reconstruction

- Cardiac surgery for intracardiac defects

Prognosis:

- Overall poor, with high mortality (30-60%)

- Complete expression of all five defects has worst prognosis

- Presence of ectopia cordis significantly decreases survival

- Survivors require close follow-up and often multiple surgeries

Bladder Exstrophy

Bladder exstrophy is a rare congenital malformation where the bladder is exposed on the lower abdominal wall due to failure of the anterior abdominal wall and bladder to close properly during embryonic development.

Embryology:

Bladder exstrophy results from incomplete closure of the lower abdominal wall and anterior bladder wall during the 4th-5th week of gestation. The cloacal membrane, which normally forms the infraumbilical abdominal wall, ruptures prematurely, leading to eversion of the posterior bladder wall.

Key Anatomical Features:

- Exposed bladder mucosa on the anterior abdominal wall

- Separation of the pubic symphysis

- Epispadias (urethral opening on the dorsal surface of the penis in males)

- Widened pubic diastasis

- Shortened penis in males, bifid clitoris in females

- Anteriorly displaced anus

Clinical Presentation:

- Visible exposed bladder mucosa at birth

- Continuous urine leakage from ureteral orifices

- Genital abnormalities

- Wide separation of pubic bones

- Low-set umbilicus or absence of umbilicus

Associated Anomalies:

- Epispadias (virtually always present)

- Vesicoureteral reflux (common)

- Inguinal hernias

- Cryptorchidism (undescended testes)

- Rectal prolapse

Management:

Treatment involves staged surgical reconstruction:

- Newborn period (48-72 hours):

- Primary bladder closure

- Approximation of pubic bones

- Partial repair of epispadias

- 6-12 months: Complete epispadias repair

- 4-5 years: Bladder neck reconstruction to achieve continence

Nursing Care:

- Immediate newborn care:

- Cover exposed bladder with plastic wrap or non-adherent dressing

- Keep bladder mucosa moist with saline

- Prevent trauma or pressure to exposed tissue

- Post-surgical care:

- Maintain immobilization (Bryant’s traction) to protect repair

- Meticulous wound care

- Urine drainage management

- Pain control

- Long-term follow-up:

- Continence assessment

- Renal function monitoring

- Urinary tract infection prevention

- Psychosocial support

Prognosis & Quality of Life

With modern staged reconstruction, patients with bladder exstrophy can achieve good functional and cosmetic outcomes. Approximately 70-80% achieve urinary continence. Fertility concerns exist, especially for females, and may require assisted reproductive technology. Psychological support for body image and sexuality is important as children develop. Long-term follow-up is necessary for monitoring renal function, continence, and sexual function.

Cloacal Exstrophy

Cloacal exstrophy is one of the most severe and complex congenital abdominal wall defects, also known as OEIS complex (Omphalocele, Exstrophy, Imperforate anus, Spinal defects). It represents the most severe form of the bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex.

Embryology:

Cloacal exstrophy results from abnormal development of the cloacal membrane and infraumbilical abdominal wall during the 4th week of gestation. The persistent cloaca fails to separate into urogenital and anorectal tracts, and premature rupture of the cloacal membrane leads to exposure of both the urinary and intestinal tracts.

Key Anatomical Features:

- Omphalocele (superior aspect)

- Bladder exstrophy (bladder halves separated by a central cecal plate)

- Exposed hindgut/terminal ileum (central cecal plate)

- Imperforate anus

- Wide pubic diastasis

- Genital anomalies (severe in both sexes)

- Spinal defects (common)

Clinical Presentation:

- Characteristic appearance at birth:

- Omphalocele superiorly

- Two bladder halves separated by intestinal mucosa

- Exposed bowel in central area (cecal plate)

- Absence of formed anus

- Severe genital anomalies:

- Males: Widely separated phallic halves, cryptorchidism

- Females: Bifid clitoris, separated labia, duplicated vagina

- Lower limb abnormalities

- Spinal deformities

Associated Anomalies:

- Spinal dysraphism (70-80%)

- Renal anomalies (40-60%)

- Tethered cord

- Cardiac defects (15-30%)

- Limb abnormalities

- Upper GI anomalies

Management:

Treatment involves complex, multistage surgical reconstruction:

- Newborn period:

- Closure of omphalocele

- Separation of bladder from intestine

- Creation of colostomy

- Preservation of gonadal tissue

- Infancy to childhood:

- Bladder closure and reconstruction

- Pubic bone approximation

- Genital reconstruction

- Spinal defect repair

- Later childhood:

- Continence procedures

- Pull-through procedure for bowel continuity

Nursing Considerations:

- Complex wound care

- Nutritional support

- Stoma management

- Pain control

- Preventing infection

- Family support and education

- Coordination of multidisciplinary care

Prognosis & Special Considerations

Cloacal exstrophy is associated with significant morbidity and previously had high mortality. With modern surgical techniques and multidisciplinary care, survival has improved to >90%. Most patients require lifetime follow-up and multiple surgeries. Quality of life challenges include:

– Urinary continence: Achieved in 50-60% of patients

– Fecal continence: Remains challenging

– Gender assignment and psychosocial issues: Particularly complex, with multidisciplinary teams including ethics specialists often involved

– Mobility: May be affected by spinal and orthopedic abnormalities

Other Related Conditions

Limb-Body Wall Complex:

- Rare, lethal malformation with:

- Large abdominal wall defect

- Thoracoschisis or thoracoabdominoschisis

- Severe limb defects

- Craniofacial anomalies

- Spinal cord abnormalities

- Cause: Vascular disruption or early amniotic band syndrome

- Prognosis: Almost uniformly fatal

- Management: Typically palliative care

Prune Belly Syndrome:

- Also called Eagle-Barrett syndrome

- Characterized by triad:

- Absence/deficiency of abdominal wall muscles

- Bilateral cryptorchidism (in males)

- Urinary tract abnormalities

- Results in wrinkled, prune-like abdominal appearance

- Management: Depends on urinary tract abnormalities

- Prognosis: Variable, depends on renal function and pulmonary development

VACTERL Association:

- Non-random association of birth defects (3+ required for diagnosis):

- Vertebral anomalies

- Anal atresia

- Cardiac defects

- Tracheo-esophageal fistula

- Esophageal atresia

- Renal anomalies

- Limb defects

- May include abdominal wall defects in some cases

- Management: Multidisciplinary approach to address each anomaly

- Prognosis: Depends on number and severity of defects

Umbilical Hernias:

- Common, typically benign defect in umbilical ring closure

- High spontaneous resolution rate by age 4-5 years

- More common in African American children and premature infants

- Management:

- Observation for most cases

- Surgical repair if persists beyond 4-5 years

- Earlier repair for large defects (>2 cm) or if symptomatic

- Excellent prognosis with low recurrence rate after repair

Nursing Care Framework for Abdominal Wall Defects

Assessment

Initial Assessment:

- Thorough physical examination:

- Characterize defect size, location, contents

- Presence/absence of covering membrane

- Integrity of exposed tissues

- Umbilical cord insertion

- Physiologic stability:

- Respiratory status and effort

- Cardiovascular assessment

- Temperature regulation

- Fluid status

- Screen for associated anomalies:

- Cardiac auscultation

- Limb anomalies

- Spinal defects

- Genitourinary abnormalities

Ongoing Assessment:

- Exposed tissues:

- Color, perfusion, edema

- Signs of ischemia or infection

- Integrity of sac (if present)

- Post-reduction monitoring:

- Abdominal compartment syndrome

- Respiratory compromise

- Lower extremity perfusion

- Urine output

- Nutritional status and GI function

- Pain and comfort levels

- Wound healing after repair

Interventions

Immediate Care:

- Protection of exposed organs:

- Sterile, moist, non-adherent dressing

- Bowel bag or silastic covering

- Avoid pressure or constriction

- Thermoregulation:

- Warming devices

- Temperature monitoring

- Minimizing heat loss from exposed viscera

- Fluid and electrolyte management:

- IV fluid resuscitation

- Replacement of third-space losses

- Monitoring of electrolytes

- Infection prevention:

- Prophylactic antibiotics

- Aseptic technique for dressing changes

Post-operative Care:

- Wound management:

- Surgical site assessment

- Dressing changes per protocol

- Monitoring for dehiscence or infection

- Respiratory support:

- Positioning to optimize ventilation

- Ventilator management if intubated

- Respiratory assessment

- Pain management:

- Age-appropriate pain assessment

- Pharmacologic interventions

- Non-pharmacologic comfort measures

- Nutritional support:

- Total parenteral nutrition

- Advancement of enteral feeds

- Monitoring for feeding intolerance

- Developmental care and positioning

Family Support

- Education:

- Condition explanation using clear terminology

- Expected course and management plan

- Surgical procedures and recovery

- Long-term prognosis

- Emotional support:

- Acknowledging parental grief and anxiety

- Providing opportunities to express concerns

- Connecting with support groups

- Referral to mental health services if needed

- Involvement in care:

- Teaching parents comfort measures

- Encouraging bonding and attachment

- Inclusion in care decisions

- Preparation for home care

Discharge Planning & Follow-up

- Home care education:

- Wound care if applicable

- Feeding techniques and schedules

- Medication administration

- Stoma care if present

- Warning signs requiring medical attention:

- Fever or infection signs

- Feeding intolerance

- Wound complications

- Respiratory distress

- Coordination of multidisciplinary follow-up:

- Surgery

- Gastroenterology

- Urology

- Developmental specialists

- Social work

- Community resources and support services

Nursing Role in Interdisciplinary Care

Nurses play a crucial role in the interdisciplinary management of abdominal wall defects by coordinating care across multiple specialties, providing continuous assessment and monitoring, serving as patient advocates, and supporting families throughout the treatment journey. The nurse is often the primary educator and contact person for families navigating the complex healthcare system, making their role essential for optimal outcomes.

Summary & Key Points

Mnemonic: “DEFECT”

Key principles in managing abdominal wall defects:

- Diagnose early (prenatal or immediate postnatal)

- Evaluate for associated anomalies

- Fluid and temperature management are critical

- Exposed organs need protection

- Coordinated multidisciplinary care

- Therapeutic support for the whole family

Key Differences

| Gastroschisis | Omphalocele |

|---|---|

| Right of umbilicus | At umbilicus |

| No protective sac | Has protective sac |

| Intestinal contents only | May include liver, other organs |

| Few associated anomalies | Many associated anomalies |

| Young maternal age risk factor | No maternal age association |

| Better prognosis | Variable prognosis |

Critical Nursing Interventions

- Protect exposed viscera from drying, trauma, and infection

- Maintain fluid balance and replace ongoing losses

- Prevent hypothermia through active warming

- Position infant to prevent vascular compromise

- Monitor for signs of abdominal compartment syndrome after reduction

- Support nutrition through parenteral and enteral approaches

- Provide developmental care and comfort measures

- Educate and support family throughout treatment journey

- Coordinate care across multiple specialties

- Prepare for discharge with comprehensive planning

Final Thoughts

The management of abdominal wall defects has improved dramatically over the past few decades, with advances in prenatal diagnosis, surgical techniques, and neonatal intensive care. Nurses play a central role in optimizing outcomes through early recognition of complications, meticulous care of exposed tissues, support of physiologic stability, and family-centered care. While these conditions present significant challenges, most affected children can lead normal lives with appropriate multidisciplinary care and support.

References and Further Reading

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn. (2020). Abdominal Wall Defects. NeoReviews, 21(6), e383-e391.

- Hopkins All Children’s Hospital. (2025). Abdominal Wall Defects. hopkinsmedicine.org

- Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. (2024). VACTERL Association (VATER syndrome). chop.edu

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Bladder Exstrophy: Causes, Symptoms & Treatment. clevelandclinic.org

- Mayo Clinic. (2025). Bladder exstrophy – Symptoms and causes. mayoclinic.org

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. (2023). Pentalogy of Cantrell – StatPearls. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

© 2025 Nursing Education Resources. Created by Soumya Ranjan Parida for educational purposes only.