Congenital Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis

Comprehensive Nursing Management Guide

Introduction

Congenital Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis (CHPS) is a relatively common gastrointestinal disorder that affects infants in the first few months of life. It is characterized by hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the circular muscle of the pylorus, leading to obstruction of the gastric outlet.

Quick Facts

- Most common cause of gastric outlet obstruction in infancy

- Typically presents at 2-6 weeks of age

- Male-to-female ratio of 4:1

- Incidence of 2-5 per 1,000 live births

- Successfully treated with surgical intervention (pyloromyotomy)

What is Pyloric Stenosis?

Pyloric stenosis occurs when the muscular layer of the pylorus (the lower portion of the stomach that connects to the small intestine) becomes abnormally thickened. This thickening narrows the pyloric canal, making it difficult for food to pass from the stomach to the intestine, resulting in forceful vomiting.

Why Nurses Need to Know

Early recognition, proper preoperative preparation, and effective postoperative care are essential for positive outcomes in infants with pyloric stenosis. Nurses play a crucial role in assessment, fluid management, family education, and monitoring for complications.

Anatomy & Pathophysiology

Normal pylorus (left) vs. Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (right)

Pathophysiology Timeline

Normal Anatomy

The pylorus is a muscular sphincter located at the distal end of the stomach. It controls the passage of food from the stomach to the duodenum through the pyloric canal.

Muscle Hypertrophy

In CHPS, the circular muscle layer of the pylorus undergoes hypertrophy (increased cell size) and hyperplasia (increased cell number).

Physiological Changes

The pylorus becomes thickened and elongated, with a consistency resembling cartilage. The pyloric canal narrows significantly.

Functional Obstruction

The narrowed pyloric canal creates a functional obstruction, preventing gastric contents from passing into the duodenum normally.

Gastric Dilation

Due to the obstruction, the stomach becomes dilated as it attempts to push contents through the narrowed opening with stronger peristaltic waves.

Metabolic Consequences

Persistent vomiting leads to loss of hydrogen and chloride ions, resulting in hypochloremic, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis and dehydration.

Proposed Theories of Development

Genetic Factors

There is evidence of familial aggregation and heritability. Male siblings of affected infants have a 5-fold increased risk. Monozygotic twins show higher concordance than dizygotic twins.

Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase Deficiency

Reduced expression of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) may contribute to pyloric muscle hypertrophy by affecting muscle relaxation.

Hormonal Influences

Some evidence suggests that increased gastrin levels and hypergastrinemia may contribute to pyloric muscle growth and hypertrophy.

Environmental Factors

Exposure to macrolide antibiotics (particularly erythromycin) in early infancy, bottle feeding instead of breastfeeding, and maternal smoking have been associated with increased risk.

Key Pathophysiological Concepts:

- Pyloric muscle thickening to 2-3 times normal size

- Elongation of the pyloric canal from 2mm to 15-20mm

- Narrowing of the pyloric lumen, sometimes to the point of complete obstruction

- Compensatory gastric muscular hypertrophy

- Antral distension proximal to the obstruction

- Progressive metabolic derangements due to persistent vomiting

Epidemiology & Risk Factors

Prevalence & Incidence

- Affects 2-5 per 1,000 live births

- More common in Caucasians than in African Americans, Hispanics, or Asians

- Predominance in males with 4-5:1 male-to-female ratio

- First-born males have the highest risk

- The incidence appears to be decreasing in recent decades

Risk Factors

- Gender: Male sex (4-5 times more common)

- Genetic predisposition: Family history, especially in first-degree relatives

- Prematurity: May develop symptoms later than full-term infants

- Feeding type: Bottle-fed infants at higher risk than breastfed infants

- Medication exposure: Macrolide antibiotics in early infancy

- Maternal factors: Smoking, younger maternal age

Risk Factor Alert

Infants exposed to erythromycin or azithromycin in the first 2 weeks of life have a 7-fold increased risk of developing pyloric stenosis. This risk decreases to 2-fold when exposure occurs between 2-6 weeks of age.

Associated Conditions

Pyloric stenosis may be associated with other congenital anomalies in 6-20% of cases, including:

Gastrointestinal

- Malrotation

- Hirschsprung disease

- Esophageal atresia

Cardiac

- Ventricular septal defect

- Atrial septal defect

- Tetralogy of Fallot

Other

- Turner syndrome

- Trisomy 18

- Cornelia de Lange syndrome

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical Presentation Timeline

Pyloric stenosis typically presents between 2-6 weeks of age, rarely before 2 weeks or after 5 months. In premature infants, symptoms may appear later than in full-term infants.

Primary Clinical Features

Projectile Vomiting

The hallmark symptom of pyloric stenosis. Initially, vomiting may be non-specific, but progresses to forceful, projectile vomiting that can travel several feet.

- Non-bilious (bile is produced beyond the obstruction)

- Occurs after feeding

- Increases in frequency and force over time

- May contain undigested milk

Palpable “Olive”

A palpable, firm, mobile mass (the hypertrophied pylorus) in the right upper quadrant or epigastrium of the abdomen in 60-80% of infants.

- Best felt when the stomach is empty, after vomiting

- Size of an olive or almond

- 1-2 cm in diameter

- Non-tender to palpation

- May be difficult to palpate in obese infants or when the stomach is distended

Secondary Clinical Features

Visible Gastric Peristalsis

Wave-like contractions moving from left to right across the upper abdomen when the infant is placed supine, especially after feeding. These represent the stomach’s attempts to overcome the obstruction.

Hunger After Vomiting

Despite forceful vomiting, infants often appear hungry and eager to feed again immediately after vomiting.

Signs of Dehydration & Malnutrition

- Poor weight gain or weight loss

- Decreased urine output (fewer wet diapers)

- Dry mucous membranes

- Sunken fontanelle

- Decreased skin turgor

- Lethargy in advanced cases

Metabolic Abnormalities

- Hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis

- Hypokalemia

- Paradoxical aciduria

- Jaundice (in approximately 2-5% of cases)

Progression of Symptoms

Initial non-specific vomiting

Progression to more forceful vomiting

Classic projectile vomiting

Poor weight gain

Dehydration & electrolyte imbalances

Severe dehydration & metabolic derangements

Mnemonic: “P.Y.L.O.R.I.C”

A mnemonic to remember the key clinical manifestations of pyloric stenosis:

Diagnostic Evaluation

Diagnostic Approach

While the clinical presentation may suggest pyloric stenosis, diagnostic confirmation is necessary before surgical intervention. The diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical findings and imaging studies.

Physical Examination

Palpation Technique for “Olive” Sign

- Position the infant supine with knees flexed

- Ensure the infant is calm (may offer pacifier or small amount of glucose water)

- If the stomach is distended, consider gastric decompression with NG tube

- Begin palpation at the right upper quadrant near the liver edge

- Use gentle, methodical palpation with the fingertips

- The olive-shaped mass is typically felt to the right of midline in the epigastrium

- Best felt immediately after the infant vomits

Observing for Visible Peristalsis

- Place the infant supine in good lighting

- Observe the epigastrium after feeding

- Look for wave-like contractions moving from left to right

- May be enhanced by giving the infant a small amount of water to drink

Laboratory Studies

Electrolyte Disturbances

Prolonged vomiting leads to characteristic metabolic abnormalities:

- Hypochloremia (Cl⁻ < 100 mEq/L)

- Hypokalemia (K⁺ < 3.5 mEq/L)

- Metabolic alkalosis (pH > 7.45, HCO₃⁻ > 26 mmol/L)

- Elevated BUN (due to dehydration)

- Hyperbilirubinemia (in some cases)

Other Laboratory Findings

- Paradoxical aciduria (despite systemic alkalosis)

- Elevated hematocrit (due to hemoconcentration)

- Occasionally elevated liver enzymes

Imaging Studies

| Imaging Modality | Findings | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound (Gold standard) |

|

|

|

| Upper GI Series (If ultrasound inconclusive) |

|

|

|

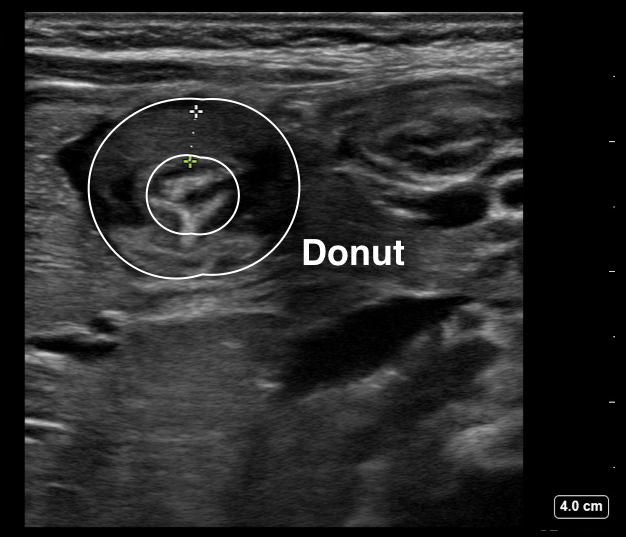

Ultrasound of pyloric stenosis showing the “donut sign” (transverse view)

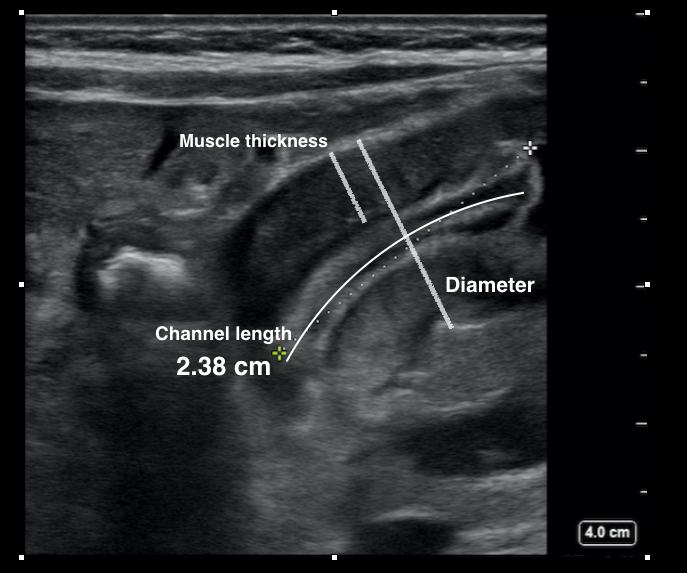

Ultrasound of pyloric stenosis showing elongated pyloric channel (longitudinal view)

Diagnostic Criteria for Congenital Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis

Diagnosis is typically confirmed when:

- Clinical presentation includes progressive non-bilious projectile vomiting in an infant 2-6 weeks of age

- Physical examination reveals a palpable olive-shaped mass in the right upper quadrant

- Ultrasound confirms pyloric muscle thickness ≥ 3mm and/or pyloric channel length ≥ 14mm

- Laboratory findings show hypochloremic, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis (in advanced cases)

Nursing Tip

When assisting with a physical examination for suspected pyloric stenosis, try to time the examination shortly after the infant has vomited when the stomach is empty. This makes the pyloric “olive” easier to palpate. Offering a pacifier or small amount of sugar water can help calm the infant during the examination.

Differential Diagnosis

Several conditions can mimic the symptoms of pyloric stenosis, particularly the vomiting. The following conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis:

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

- More common than pyloric stenosis

- Typically non-projectile regurgitation

- Present from birth (versus 2-6 weeks for pyloric stenosis)

- No palpable olive or visible peristalsis

- No dehydration or electrolyte imbalances

- May have associated irritability, arching, or feeding refusal

Gastroenteritis

- Usually acute onset

- Often accompanied by diarrhea

- May have fever

- Vomiting is not consistently projectile

- No palpable olive

- May affect other family members

Intestinal Malrotation with Volvulus

- Surgical emergency

- Bilious vomiting (key distinguishing feature from pyloric stenosis)

- Abdominal distention and tenderness

- Rapid clinical deterioration

- Can present at any age, but often in first month of life

Formula Intolerance

- Non-projectile vomiting and regurgitation

- Often with fussiness, excessive gas, and loose stools

- No palpable olive

- Symptoms improve with formula change

- No dehydration or weight loss if managed appropriately

Adrenal Crisis/Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

- Vomiting with dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities

- Poor weight gain

- Hyperpigmentation of genitalia and skin creases

- Ambiguous genitalia in females

- Hyponatremia and hyperkalemia (versus hypokalemia in pyloric stenosis)

Other Conditions to Consider

- Hiatal hernia

- Pylorospasm

- Increased intracranial pressure

- Urinary tract infection

- Metabolic disorders

- Inborn errors of metabolism

Key Distinguishing Features of Pyloric Stenosis

- Projectile, non-bilious vomiting

- Palpable olive-shaped mass

- Visible gastric peristalsis

- Onset between 2-6 weeks of age

- Hungry after vomiting

- Hypochloremic, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis

- Ultrasound confirmation with specific measurements

Medical & Surgical Management

Preoperative Management

Before surgical intervention, the primary focus is on stabilizing the infant’s condition and correcting fluid and electrolyte imbalances:

Fluid & Electrolyte Resuscitation

- IV fluid administration with 5% dextrose in 0.45% saline

- Initial fluid bolus (20ml/kg) of isotonic crystalloid for dehydration

- Maintenance fluids based on weight and degree of dehydration

- Potassium supplementation (after confirming adequate urine output)

- Correction of hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis

Laboratory Targets Before Surgery

- Serum chloride > 100 mmol/L

- Serum potassium > 3.5 mmol/L

- Bicarbonate < 26 mmol/L

- pH < 7.45

- Base excess < 3.5

- Sodium > 132 mmol/L

Nasogastric Tube Placement

- Helps decompress the stomach

- Prevents aspiration of gastric contents

- Reduces vomiting during preoperative period

- May be used for gastric lavage to remove residual gastric contents before anesthesia

Critical Consideration

Metabolic alkalosis must be corrected before surgery as it can lead to respiratory depression and apnea during anesthesia. The time required for preoperative optimization is typically 24-48 hours, depending on the severity of dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities.

Surgical Intervention

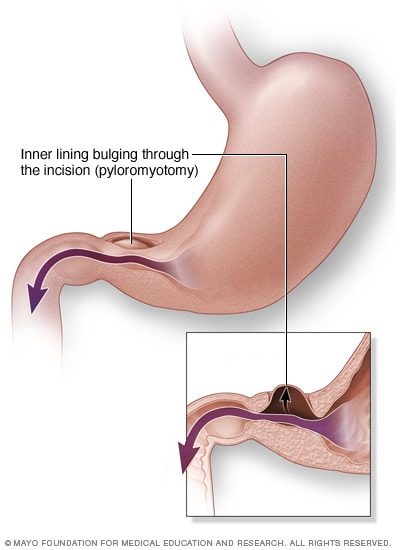

Pyloromyotomy procedure showing incision of the thickened pyloric muscle

Pyloromyotomy (Ramstedt Procedure)

The definitive treatment for pyloric stenosis is a surgical procedure called a pyloromyotomy:

- Longitudinal incision through the serosal and muscular layers of the pylorus

- Careful separation of the hypertrophied muscle fibers

- Preservation of the intact mucosa

- The incision allows the mucosa to bulge through, effectively widening the pyloric channel

Surgical Approaches

Two main surgical approaches are used:

1. Open Pyloromyotomy

- Right upper quadrant transverse incision (RUQ)

- Traditional approach with excellent visibility

- Allows direct palpation of the pylorus

- Larger incision with more visible scar

2. Laparoscopic Pyloromyotomy

- 3-4 small port sites

- Minimally invasive with faster recovery

- Less postoperative pain

- Improved cosmetic outcome

- Shorter hospital stay

Surgical Outcomes

Pyloromyotomy has an excellent prognosis with a success rate of over 95%. Surgical complications are rare but may include:

- Mucosal perforation (1-2%)

- Incomplete pyloromyotomy (1-4%)

- Wound infection

- Delayed gastric emptying

Postoperative Management

Feeding Protocol

Two approaches to postoperative feeding may be used:

Ad Libitum Feeding

- Feeding on demand when the infant is awake and hungry

- Associated with shorter hospital stay

- May lead to more vomiting episodes initially

Graded Feeding Schedule

- Start with clear liquids (Pedialyte) 4-6 hours post-surgery

- Progress to 1/2 strength formula/breast milk

- Advance to full strength formula/breast milk

- Gradual increase in volume

- Timing between feedings typically 3-4 hours

Common Postoperative Issues

Vomiting

- Occurs in 40-85% of infants after surgery

- Usually resolves within 24-48 hours

- Rarely persists beyond 5 days

- Managed by temporarily slowing feeding advancement

Pain Management

- Acetaminophen for mild to moderate pain

- Minimizing opioid use to prevent respiratory depression

- Local anesthetic at incision sites

Discharge Criteria

- Tolerating full feeds

- Minimal or no vomiting

- Voiding normally

- Afebrile

- Adequate pain control with oral medications

Parent Education for Discharge

- Incision care (keeping the area clean and dry)

- Positioning after feeds (upright for 30 minutes)

- Feeding techniques (paced feeding, frequent burping)

- Signs of complications requiring medical attention

- Follow-up appointment scheduling

- Reassurance that occasional vomiting may continue for a few days but should gradually resolve

Nursing Management (ADPIE Framework)

The ADPIE Nursing Process

The nursing care of infants with congenital hypertrophic pyloric stenosis follows the ADPIE framework: Assessment, Diagnosis, Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation.

Assessment

Health History

- Feeding pattern and tolerance

- Vomiting characteristics (timing, frequency, force, content)

- Stool and urine output (frequency, consistency, volume)

- Medications (especially recent antibiotics)

- Family history (pyloric stenosis or other GI conditions)

- Growth patterns and recent weight changes

- Sleep patterns and irritability

Physical Assessment

- Vital signs (heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, temperature)

- Weight and length measurements (plot on growth chart)

- Hydration status assessment

- Anterior fontanelle (sunken or flat)

- Mucous membranes (dry or moist)

- Skin turgor

- Capillary refill time

- Presence of tears when crying

- Abdominal assessment

- Inspection for visible peristaltic waves

- Auscultation of bowel sounds

- Palpation for the pyloric “olive”

- Assessment of abdominal distension

Laboratory & Diagnostic Monitoring

- Electrolyte levels (sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate)

- Acid-base status (pH, base excess)

- BUN and creatinine (to assess kidney function and dehydration)

- Glucose level

- Bilirubin level (if jaundice is present)

- Imaging studies (ultrasound findings or other diagnostic tests)

Assessment Tips

- Document and measure vomitus when possible to track fluid losses

- Weigh diapers to track urine output (1g = 1mL)

- Observe and document feeding behaviors, including hunger cues and satiety

- Assess parents’ understanding of the condition and their anxiety level

Nursing Diagnoses

Based on the comprehensive assessment, the following nursing diagnoses are commonly appropriate for infants with pyloric stenosis:

Deficient Fluid Volume

Related to: Prolonged vomiting, inadequate fluid intake, and inability to retain oral fluids

As evidenced by: Decreased urine output, dry mucous membranes, sunken fontanelle, poor skin turgor, concentrated urine, abnormal electrolyte levels, and weight loss

Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements

Related to: Inability to retain nutrients due to projectile vomiting and gastric outlet obstruction

As evidenced by: Weight loss or inadequate weight gain, poor feeding tolerance, persistent hunger after vomiting, and decreased subcutaneous fat

Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity

Related to: Dehydration, poor nutritional status, and potential for skin breakdown from vomitus on perioral/neck areas

As evidenced by: Dry skin, reduced turgor, and irritation around mouth and neck from stomach acid in vomitus

Risk for Aspiration

Related to: Frequent projectile vomiting, delayed gastric emptying, and presence of nasogastric tube

As evidenced by: Episodes of vomiting, especially during or after feeding

Acute Pain

Related to: Surgical incision and manipulation of tissues following pyloromyotomy

As evidenced by: Crying, facial grimacing, guarding of the abdomen, irritability, and changes in vital signs

Anxiety (Parental)

Related to: Child’s illness, hospitalization, surgical intervention, and unfamiliar environment

As evidenced by: Expressed concerns, questions, nervousness, increased tension, and difficulty focusing on explanations

Risk for Ineffective Breathing Pattern

Related to: Metabolic alkalosis affecting respiratory drive, pain, and effects of anesthesia

As evidenced by: Changes in respiratory rate, depth, or pattern, particularly postoperatively

Planning

Expected Outcomes

Short-term Goals (Preoperative)

- The infant will demonstrate improved hydration status within 24 hours as evidenced by:

- Moist mucous membranes

- Normal skin turgor

- Urine output ≥ 1-2 mL/kg/hr

- Fontanelle flat and soft

- The infant will have electrolyte levels within normal ranges prior to surgery

- The infant will have a stable acid-base balance (pH < 7.45) prior to surgery

- Parents will verbalize understanding of the condition and surgical procedure

Short-term Goals (Postoperative)

- The infant will maintain patent airway and adequate oxygenation

- The infant will demonstrate adequate pain control as evidenced by:

- Appropriate pain scale scores for age

- Periods of restful sleep

- Reduced irritability

- The infant will tolerate incremental feeding advancement without significant vomiting

- The infant’s surgical incision will remain clean, dry, and intact

Long-term Goals

- The infant will regain and maintain appropriate weight for age

- The infant will demonstrate normal feeding patterns without vomiting

- The infant will have complete healing of surgical incision without complications

- Parents will demonstrate confidence in caring for their infant at home

- The infant will resume normal developmental progression

Interdisciplinary Collaboration

The care plan for an infant with pyloric stenosis should involve collaboration with:

- Pediatric surgeon

- Pediatrician

- Anesthesiologist

- Pediatric nurse practitioners

- Nutritionist/dietitian

- Social worker (for family support needs)

- Lactation consultant (for breastfeeding mothers)

Implementation

Preoperative Nursing Interventions

- Administer IV fluids as prescribed to correct dehydration and electrolyte imbalances

- Monitor IV site for patency and signs of infiltration or phlebitis

- Maintain accurate intake and output records

- Weigh diapers to quantify urine output

- Measure and document characteristics of vomitus

- Monitor vital signs every 4 hours or as ordered

- Assess fontanelle, mucous membranes, and skin turgor every 4 hours

- Monitor laboratory values (electrolytes, pH, bicarbonate) and report abnormalities

- Maintain NPO status as ordered preoperatively

- Insert and maintain nasogastric tube as ordered for gastric decompression

- Weigh infant daily at the same time and on the same scale

- Provide pacifier for non-nutritive sucking needs

- Document feeding tolerance once oral feeding is resumed

- Keep skin clean and dry, especially around the mouth and neck after vomiting

- Apply protective barrier to skin areas exposed to gastric acid

- Change position regularly to prevent pressure areas

- Provide gentle cleansing after each vomiting episode

- Explain the condition, diagnostic tests, and treatment plan using simple language

- Provide information about the surgical procedure and expected outcomes

- Encourage questions and address parental concerns

- Explain the preoperative preparation process

- Involve parents in the infant’s care as appropriate

- Provide emotional support and reassurance

Postoperative Nursing Interventions

- Position infant to promote optimal respiratory function

- Monitor oxygen saturation continuously for the first 24 hours

- Assess respiratory rate, depth, and effort every 2-4 hours

- Provide oxygen as ordered

- Suction airway as needed

- Elevate head of bed 30 degrees after feeding to reduce risk of aspiration

- Assess incision site every 4 hours for signs of infection, bleeding, or dehiscence

- Maintain clean, dry dressing as ordered

- Perform dressing changes using sterile technique if ordered

- Document appearance of incision site

- Monitor temperature for signs of infection

- Teach parents proper incision care for discharge

- Assess pain using age-appropriate pain scale (FLACC, NIPS)

- Administer analgesics as ordered and evaluate effectiveness

- Implement non-pharmacological pain relief measures:

- Swaddling

- Gentle rocking

- Pacifier with sucrose solution

- Distraction with soft music or mobile

- Position infant to minimize incisional pain

- Handle the infant gently during care activities

- Follow prescribed feeding protocol (ad libitum or graded)

- Start with clear liquids in small amounts as ordered

- Advance diet as tolerated per protocol

- Feed in upright position

- Burp the infant frequently during and after feedings

- Keep the infant in upright position for 30 minutes after feeding

- Document feeding tolerance, amount taken, and any vomiting episodes

- Weigh infant daily to monitor weight gain

- Teach parents proper feeding techniques:

- Proper positioning during and after feeding

- Paced feeding techniques

- Proper burping techniques

- Provide incision care instructions:

- Keeping the area clean and dry

- Avoiding tub baths until cleared by surgeon

- Signs of infection to report

- Discuss return to normal activity and limitations

- Review signs/symptoms requiring medical attention:

- Persistent or increasing vomiting

- Fever

- Decreased oral intake

- Signs of dehydration

- Incision site redness, drainage, or opening

- Provide written instructions for all teaching points

- Schedule follow-up appointments

Evaluation

Evaluation of nursing interventions involves assessing the infant’s progress toward the established goals and outcomes. The following criteria indicate successful management:

Fluid and Electrolyte Balance

- Maintenance of normal hydration status:

- Moist mucous membranes

- Flat fontanelle

- Good skin turgor

- Adequate urine output (1-2 mL/kg/hour)

- Electrolyte levels within normal ranges:

- Sodium: 135-145 mEq/L

- Potassium: 3.5-5.0 mEq/L

- Chloride: 98-106 mEq/L

- Bicarbonate: 22-26 mEq/L

- Acid-base balance normalized (pH 7.35-7.45)

Nutritional Status

- Successful transition to oral feedings

- Tolerance of age-appropriate feeding volumes without significant vomiting

- Consistent weight gain pattern (20-30g/day)

- Normal feeding behaviors and hunger cues

- Stable or improving weight curve on growth chart

Respiratory Status

- Normal respiratory rate, effort, and pattern for age

- Oxygen saturation maintained at 95% or greater on room air

- Clear breath sounds on auscultation

- No signs of respiratory distress or aspiration

Pain Management

- Pain scores consistently within acceptable range

- Infant consolable and able to sleep comfortably

- Minimal irritability

- Transition to oral pain management if needed

Wound Healing

- Incision site clean, dry, and intact

- No signs of infection (redness, warmth, drainage, tenderness)

- Progressive healing of surgical wound

- No complications such as dehiscence or hernia formation

Parent Education

- Parents can verbalize understanding of:

- The condition and surgical correction

- Medication administration (if applicable)

- Proper feeding techniques

- Wound care

- Signs that require medical attention

- Parents demonstrate confidence in providing care

- Parents can identify appropriate follow-up resources

Expected Outcomes Timeline

- 24-48 hours postop: Stabilization of fluid and electrolyte balance, resumption of oral feeding, pain controlled

- 48-72 hours postop: Significant reduction in vomiting, consistent tolerance of feedings, beginning of weight gain

- Discharge (typically day 2-4): Full feeding tolerance, minimal or no vomiting, stable vital signs, parents confident in home care

- 1-2 weeks post-discharge: Complete resolution of vomiting, consistent weight gain, well-healing incision

- Long-term: Normal growth and development, no recurrence of symptoms

When to Revise the Care Plan

The nursing care plan should be revised if the infant:

- Continues to have significant vomiting 48 hours after surgery

- Fails to gain weight despite adequate intake

- Develops signs of surgical complications (infection, incomplete pyloromyotomy)

- Shows persistent pain despite appropriate management

- Exhibits signs of aspiration or respiratory compromise

- Has parental concerns or special needs not addressed in the current plan

Complications & Prevention

Potential Complications

Preoperative Complications

- Severe Dehydration: Can lead to hypovolemic shock if untreated

- Electrolyte Imbalances: Particularly hypochloremic, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis

- Malnutrition: From persistent vomiting and inadequate nutrient retention

- Hematemesis: Small amounts of blood in vomitus from irritation of the gastric mucosa

- Jaundice: Occurs in a small percentage of infants with pyloric stenosis

- Aspiration Pneumonia: From inhalation of vomitus

Surgical Complications

- Mucosal Perforation: Occurs in 1-2% of cases during pyloromyotomy

- Incomplete Pyloromyotomy: Inadequate division of the pyloric muscle (1-4%)

- Wound Infection: More common with open surgical approach

- Wound Dehiscence: Separation of the surgical incision

- Anesthesia Complications: Particularly related to metabolic alkalosis

Postoperative Complications

- Persistent Vomiting: Common initially but should resolve within 2-3 days

- Dumping Syndrome: Rapid gastric emptying after correction

- Adhesions: Rare but can lead to intestinal obstruction

- Incisional Hernia: Weakness at the surgical site

- Gastroesophageal Reflux: May persist or develop after surgery

Prevention & Monitoring

Preventing Preoperative Complications

- Early recognition and diagnosis of pyloric stenosis

- Thorough correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalances before surgery

- Careful nasogastric tube management to prevent aspiration

- Positioning infant with head elevated to reduce risk of aspiration

- Frequent monitoring of vital signs and hydration status

Preventing Surgical Complications

- Complete correction of metabolic alkalosis prior to anesthesia

- Proper surgical technique by experienced pediatric surgeons

- Adequate exposure and visualization during the procedure

- Careful handling of the pyloric muscle during pyloromyotomy

- Intraoperative confirmation of complete myotomy

Preventing Postoperative Complications

- Appropriate feeding advancement protocol

- Proper positioning after feedings (upright for 30 minutes)

- Meticulous wound care and infection prevention practices

- Early ambulation and movement as appropriate for age

- Regular follow-up to monitor growth and development

Long-term Monitoring

After recovery from pyloric stenosis, infants should have:

- Regular pediatric check-ups to monitor growth and weight gain

- Developmental screening as part of routine care

- Initial surgical follow-up at 2-4 weeks after discharge

- No special long-term dietary restrictions or limitations

- No increased risk for other gastrointestinal disorders

Prognosis

The overall prognosis for infants with pyloric stenosis is excellent:

- Nearly 100% surgical success rate with pyloromyotomy

- Very low mortality rate (less than 0.5%)

- Complete recovery in most cases with no long-term effects

- Normal growth and development following recovery

- No increased risk of gastrointestinal problems later in life

- No special follow-up needed beyond standard pediatric care after initial recovery

Concept Mindmap

Conceptual overview of Congenital Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis

Case Study

Case Presentation: 4-Week-Old Male with Projectile Vomiting

Patient Information

Patient: 4-week-old male infant, first-born child

Chief Complaint: Progressively worsening vomiting for 1 week

History of Present Illness

Parents report that the infant began having episodes of vomiting about 1 week ago. Initially, the vomiting occurred occasionally after feeds, but has progressed to forceful, projectile vomiting after almost every feeding. The vomitus is non-bilious and consists of undigested formula. Despite the vomiting, the infant appears hungry and eager to feed immediately afterward. The parents note decreased wet diapers over the past 24 hours.

Physical Examination

- Vital signs: HR 162, RR 48, Temp 37.0°C

- Weight: 3.6 kg (birth weight 3.8 kg)

- General: Alert but showing signs of mild dehydration

- HEENT: Sunken fontanelle, dry mucous membranes

- Abdomen: Visible peristaltic waves moving from left to right; palpable “olive” in right upper quadrant

- Skin: Decreased turgor, no rash

Diagnostic Studies

- Electrolytes: Na 136 mEq/L, K 3.2 mEq/L, Cl 94 mEq/L, HCO3 28 mEq/L

- Blood gas: pH 7.48, indicating metabolic alkalosis

- Ultrasound: Pyloric muscle thickness 4.2 mm, pyloric channel length 18 mm

Diagnosis

Congenital Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis with mild to moderate dehydration and metabolic alkalosis

Management Plan

- NPO status and insertion of nasogastric tube for gastric decompression

- IV fluid resuscitation with 5% dextrose in 0.45% saline with potassium supplementation

- Correction of electrolyte abnormalities and metabolic alkalosis

- Surgical consultation for pyloromyotomy

- Preoperative nursing care focusing on hydration, comfort, and parental support

- Surgical intervention (pyloromyotomy) once metabolically stable

- Postoperative feeding protocol and monitoring

Case Resolution

The infant received 24 hours of IV fluid therapy to correct dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. Once laboratory values were within normal limits, he underwent a successful laparoscopic pyloromyotomy. Feedings were started 6 hours after surgery using a graded approach, beginning with Pedialyte and advancing to full-strength formula. Some mild vomiting occurred on the first postoperative day but resolved by the second day. The infant was discharged home on postoperative day 3 with appropriate weight gain and good feeding tolerance. Two-week follow-up showed continued weight gain and complete resolution of symptoms.

Summary & Key Points

Pathophysiology

- Hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the pyloric muscle

- Narrowing of the pyloric canal causing gastric outlet obstruction

- Multiple theories regarding etiology (genetic, neuronal, hormonal)

- Risk factors include male gender, firstborn status, and macrolide exposure

Clinical Presentation

- Onset at 2-6 weeks of age

- Progressive, non-bilious, projectile vomiting

- Palpable “olive” mass in right upper quadrant

- Visible gastric peristalsis

- Signs of dehydration and weight loss

- Hypochloremic, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis

Diagnosis

- Clinical examination (palpation of olive, visible peristalsis)

- Ultrasound (gold standard): pyloric muscle thickness ≥ 3mm, length ≥ 14mm

- Upper GI series if ultrasound inconclusive

- Laboratory evaluation of electrolytes and acid-base status

Management

- Preoperative fluid and electrolyte correction

- Nasogastric decompression

- Pyloromyotomy (Ramstedt procedure) – open or laparoscopic

- Postoperative feeding advancement

- Pain management and wound care

- Parental education for home care

Mnemonic: “S.T.E.N.O.S.I.S”

A comprehensive mnemonic for remembering key aspects of pyloric stenosis management:

Key Nursing Considerations

- Monitor for signs of dehydration and electrolyte imbalances

- Maintain accurate intake and output records

- Assess surgical incision for signs of infection or complications

- Implement proper feeding techniques to reduce postoperative vomiting

- Provide comprehensive discharge education to parents

- Follow up on growth and developmental progress

References & Resources

References

- Hernanz-Schulman, M. (2003). Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Radiology, 227(2), 319-331.

- Peters, B., Oomen, M. W., Bakx, R., & Benninga, M. A. (2014). Advances in infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 8(5), 533-541.

- Sullivan, K. J., Chan, E., Vincent, J., et al. (2016). Feeding post-pyloromyotomy: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 137(1), e20152550.

- Krogh, C., Fischer, T. K., Skotte, L., et al. (2010). Familial aggregation and heritability of pyloric stenosis. JAMA, 303(23), 2393-2399.

- Garfield, K., & Sergent, S. R. (2023). Pyloric stenosis. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Feenstra, B., Geller, F., Carstensen, L., et al. (2013). Plasma lipids, genetic variants near APOA1, and the risk of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. JAMA, 310(7), 714-721.

- McAteer, J. P., Ledbetter, D. J., & Goldin, A. B. (2013). Role of bottle feeding in the etiology of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(12), 1143-1149.

- Dalton, B. G., Gonzalez, K. W., Boda, S. R., Thomas, P. G., Sherman, A. K., & St Peter, S. D. (2016). Optimizing fluid resuscitation in hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 51(8), 1279-1282.

- Eberly, M. D., Eide, M. B., Thompson, J. L., & Nylund, C. M. (2015). Azithromycin in early infancy and pyloric stenosis. Pediatrics, 135(3), 483-488.

- Hong, Y., Okolo, F., Morgan, K., et al. (2022). Safety and benefit of ad libitum feeding following laparoscopic pyloromyotomy: retrospective comparative trial. Pediatric Surgery International, 38(4), 555-558.

Additional Resources

- American Academy of Pediatrics – https://www.aap.org

- Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center – Pyloric Stenosis Information – https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/health/p/pyloric-stenosis

- Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia – Pyloric Stenosis – https://www.chop.edu/conditions-diseases/pyloric-stenosis

- Mayo Clinic – Pyloric Stenosis – https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pyloric-stenosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20351416

- Medscape – Infantile Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis – https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/929829-overview