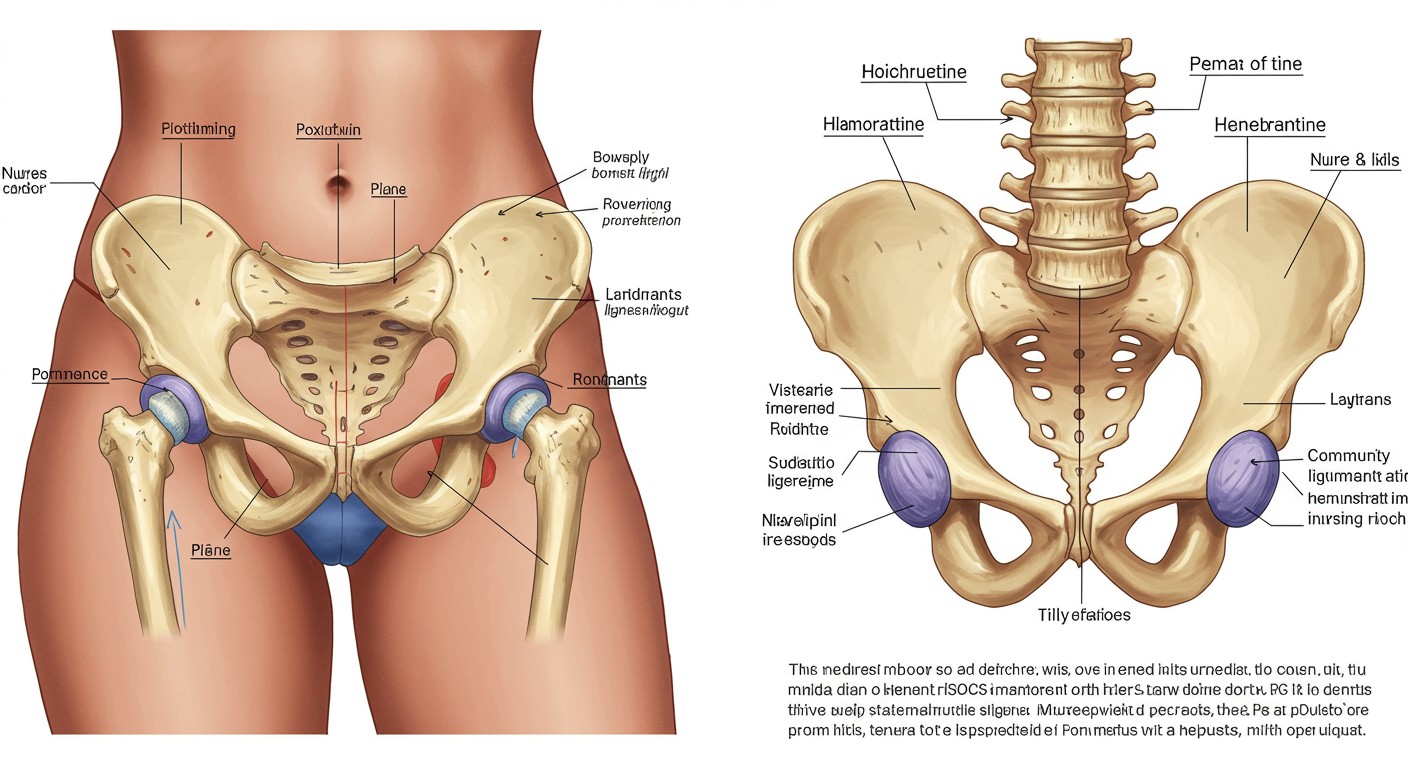

Female Pelvis Anatomy

Comprehensive Nursing Notes from a obstetrics and gynecological nursing

A detailed guide for nursing students on the anatomical structures and clinical significance of the female pelvis

Table of Contents

Introduction to Female Pelvis

The female pelvis serves as a crucial anatomical structure that plays several vital roles in women’s health. From a community health nursing perspective, understanding the pelvis anatomy is essential for assessing reproductive health, providing antenatal care, managing labor, and addressing various gynecological conditions.

The female pelvis differs significantly from its male counterpart in structure and dimensions. These differences primarily support childbearing and delivery functions. As community health nurses, recognizing these anatomical distinctions is critical for providing effective care across various settings.

Community Health Nursing Context:

Understanding pelvic anatomy informs assessments, interventions, and education in prenatal care, sexual health counseling, family planning services, and women’s wellness programs in community settings.

Bones of the Female Pelvis

The female pelvis is formed by four bones that connect to create a basin-like structure. Understanding these bones is fundamental to comprehending pelvic anatomy.

| Bone | Description | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Sacrum | Triangular bone formed by five fused sacral vertebrae. In females, it’s shorter, wider, and has a greater anterior concavity. | Provides support for the spine and connects to the ilium forming the sacroiliac joints. The curvature affects the pelvic outlet dimensions. |

| Coccyx | Small triangular bone at the base of the spine, consisting of 3-5 fused vertebrae. | Provides attachment for the muscles of the pelvic floor. Can recede during childbirth to increase the antero-posterior diameter of the pelvic outlet. |

| Hip Bones (2) | Each hip bone (os coxae) consists of three fused bones: ilium, ischium, and pubis. | Form the lateral and anterior walls of the pelvis. Their shape and orientation significantly influence pelvic type classification. |

Components of Each Hip Bone

- Ilium: The largest portion of the hip bone, forming the upper part. The iliac crest is palpable at the waist and serves as an important landmark. The iliac fossae are more shallow and spread out in females.

- Ischium: Forms the posteroinferior portion of the hip bone. The ischial tuberosity supports body weight in a sitting position and is an important landmark for pelvic measurements.

- Pubis: Forms the anterior portion of the hip bone. The two pubic bones meet at the pubic symphysis. In females, the pubic arch is typically wider (>90°) compared to males.

Community Health Assessment Note:

When conducting antenatal assessments in community settings, nurses should understand that pelvic bone structure variations may influence pregnancy progression and delivery options. Knowledge of normal anatomy helps identify potential complications.

Joints and Articulations of the Pelvis

The joints of the female pelvis provide both stability and limited mobility essential for childbirth. Understanding these articulations is crucial for community health nurses when assessing pregnancy-related pelvic changes.

Sacroiliac Joints

Strong, synovial joints between the sacrum and ilium. During pregnancy, hormones (particularly relaxin) cause these joints to become more mobile, allowing slight movement during delivery.

Clinical significance: Sacroiliac joint dysfunction can cause lower back pain, which is a common complaint during pregnancy and postpartum periods.

Pubic Symphysis

A fibrocartilaginous joint between the two pubic bones. The interpubic disc widens during pregnancy (by 3-8mm) and allows slight movement.

Clinical significance: Pubic symphysis dysfunction can cause significant pain in the anterior pelvis during pregnancy and may require supportive interventions.

Sacrococcygeal Joint

A slightly movable symphysis between the sacrum and coccyx. This joint allows the coccyx to move posteriorly during childbirth, increasing the antero-posterior diameter of the pelvic outlet.

Clinical significance: Trauma during difficult deliveries can cause coccygeal pain (coccydynia) that may persist postpartum.

Lumbosacral Joint

The articulation between the fifth lumbar vertebra and the sacrum. This joint forms the lumbosacral angle, which affects pelvic inclination.

Clinical significance: Changes in this joint during pregnancy contribute to the characteristic lordosis and can lead to lower back pain.

Community Health Intervention Note:

When conducting prenatal education sessions in community settings, nurses should explain the normal joint changes during pregnancy. Teaching about proper body mechanics and exercises to support pelvic joints can help prevent discomfort and injury.

Ligaments of the Pelvis

The female pelvis contains numerous ligaments that provide stability while allowing for the flexibility needed during childbirth. These ligaments undergo significant changes during pregnancy and childbirth.

| Ligament | Location | Function | Changes During Pregnancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior Sacroiliac | Anterior surface of sacroiliac joint | Reinforces the anterior aspect of the sacroiliac joint | Becomes more elastic due to hormonal influences |

| Posterior Sacroiliac | Posterior surface of sacroiliac joint | Provides major stability to the sacroiliac joint | Relaxes slightly to allow joint movement |

| Sacrospinous | From sacrum to ischial spine | Stabilizes the sacrum and divides the pelvic cavity from the perineum | Undergoes slight relaxation |

| Sacrotuberous | From sacrum to ischial tuberosity | Prevents sacral rotation and stabilizes the pelvis | Maintains significant tension even during pregnancy |

| Iliolumbar | From transverse process of L5 to iliac crest | Stabilizes the lumbosacral junction | May be strained due to postural changes |

| Superior Pubic | Upper surface of pubic symphysis | Reinforces the pubic symphysis superiorly | Becomes more elastic and may stretch |

| Arcuate Pubic | Inferior aspect of pubic symphysis | Reinforces the pubic symphysis inferiorly | Becomes more elastic, allowing for wider pubic angle |

Supporting Ligaments of Female Reproductive Organs

Several ligaments support the uterus and ovaries within the pelvic cavity:

- Broad Ligament: A peritoneal fold that extends from the lateral margins of the uterus to the pelvic wall, creating a partition in the pelvic cavity.

- Round Ligament: Extends from the lateral aspect of the uterus to the labia majora through the inguinal canal. It helps maintain the anteverted position of the uterus.

- Uterosacral Ligaments: Extend from the cervix to the sacrum, providing posterior support to the uterus.

- Cardinal Ligaments (Mackenrodt’s ligaments): Extend from the cervix and vagina laterally to the pelvic wall, providing significant support to the uterus.

Community Health Assessment Tip:

When assessing pregnant women in community settings, understand that pelvic ligament pain (especially in the pubic symphysis and sacroiliac joints) is common. Differentiate normal pregnancy-related discomfort from pathological conditions requiring referral.

Pelvic Planes

The pelvis has several important planes that are crucial for understanding the passage of the fetus through the birth canal. These planes help community health nurses assess the likelihood of successful vaginal deliveries.

Plane of Pelvic Inlet

Boundaries: Sacral promontory posteriorly, linea terminalis laterally, and pubic crest anteriorly.

Significance: The first pelvic plane the fetal head encounters. Contraction or abnormality in this plane can prevent engagement of the fetal head.

Plane of Greatest Pelvic Dimensions

Boundaries: Middle of the third sacral vertebra, middle of the acetabulum, and middle of the symphysis pubis.

Significance: Widest part of the pelvic cavity, typically allowing easy passage of the fetus.

Plane of Least Pelvic Dimensions

Boundaries: Sacrococcygeal joint posteriorly, ischial spines laterally, and lower border of symphysis pubis anteriorly.

Significance: Narrowest part of the pelvic cavity. Ischial spines are important landmarks for assessing fetal descent during labor.

Plane of Pelvic Outlet

Boundaries: Tip of coccyx posteriorly, ischial tuberosities laterally, and inferior margin of symphysis pubis anteriorly.

Significance: The final pelvic plane the fetus passes through during delivery. The mobility of the coccyx can increase the anteroposterior diameter.

Pelvic Axis (Curve of Carus)

The pelvic axis is an imaginary curved line that passes through the center of each pelvic plane, showing the path the fetus must follow through the birth canal. This J-shaped curve demonstrates why the direction of fetal movement changes during delivery—first downward and backward, then downward and forward.

Community Health Nursing Application:

Understanding pelvic planes helps community health nurses explain the mechanism of labor to pregnant women during antenatal education. This knowledge also helps identify when labor progress deviates from the expected pattern, potentially necessitating referral to specialized care.

Pelvic Diameters

The dimensions of the female pelvis are crucial for assessing the adequacy of the birth canal. Community health nurses use this knowledge when performing antenatal assessments and providing education about childbirth.

Pelvic Inlet Diameters

| Diameter | Measurement Points | Normal Value (cm) | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anteroposterior (Obstetric Conjugate) |

From sacral promontory to closest point on symphysis pubis | 11.5 | Most critical diameter for initial engagement of fetal head |

| Transverse | Greatest distance between the iliopectineal lines | 13.5 | Typically generous in females but may be restricted in certain pelvic types |

| Oblique | From sacroiliac joint to the iliopectineal eminence of the opposite side | 12.5 | Often used by the fetal head when entering the pelvic inlet |

Midpelvic (Cavity) Diameters

| Diameter | Measurement Points | Normal Value (cm) | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anteroposterior | From middle of posterior surface of symphysis pubis to junction of S2 and S3 | 12.5 | Usually adequate if inlet and outlet are normal |

| Transverse (Interspinous) |

Distance between ischial spines | 10.5 | Critical dimension; often the narrowest part of the pelvic cavity |

Pelvic Outlet Diameters

| Diameter | Measurement Points | Normal Value (cm) | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anteroposterior | From lower border of symphysis pubis to tip of coccyx | 11.5-12.5 | Can increase during delivery due to movement of the coccyx |

| Transverse (Intertuberous) |

Distance between inner borders of ischial tuberosities | 11.0 | Critical for successful delivery; significantly wider in females than males |

| Posterior Sagittal | From middle of intertuberous diameter to sacrococcygeal joint | 7.5 | Important for fetal head rotation during delivery |

Mnemonic for Pelvic Diameters: “In-Mid-Out”

- INlet: AP = 11.5, Transverse = 13.5 (Wide transversely)

- MIDpelvis: AP = 12.5, Interspinous = 10.5 (Nearly round)

- OUTlet: AP = 12.5, Intertuberous = 11.0 (Wide anteroposteriorly)

Community Health Assessment Note:

While direct measurement of internal pelvic diameters is not feasible in community settings, indirect assessments can help identify women who may need specialized evaluation. External measurements such as the diagonal conjugate (accessible during vaginal examination) may be used to estimate internal dimensions.

Important Landmarks of the Female Pelvis

The female pelvis has several anatomical landmarks that serve as critical reference points for assessing pelvic dimensions, fetal position, and labor progress. Community health nurses should be familiar with these landmarks for effective antenatal care.

Anterior Landmarks

- Symphysis Pubis: The joint between the two pubic bones, serving as an anterior reference point for pelvic measurements.

- Pubic Arch: Formed by the conjoined rami of the pubic bones. In females, this angle is typically >90° (compared to <70° in males).

- Pubic Crest: Superior border of the pubic bone, palpable through the abdominal wall.

- Iliopectineal Eminence: Marks the junction between the ilium and pubis on the iliopectineal line.

Posterior Landmarks

- Sacral Promontory: The anterior projection of the first sacral vertebra into the pelvic inlet, crucial for measuring the obstetric conjugate.

- Sacral Hollow: The concave anterior surface of the sacrum, more pronounced in females.

- Sacral Hiatus: An opening in the posterior sacral wall where the sacral canal ends.

- Coccyx: The small bone at the end of the vertebral column, important for the anteroposterior diameter of the outlet.

Lateral Landmarks

- Iliac Crest: The superior curved border of the ilium, palpable at the waist level.

- Anterior Superior Iliac Spine (ASIS): The anterior end of the iliac crest, an important external landmark.

- Posterior Superior Iliac Spine (PSIS): The posterior end of the iliac crest, visible as dimples on the lower back.

- Ischial Spine: Projects into the pelvic cavity and serves as a critical landmark for assessing fetal descent during labor.

- Ischial Tuberosity: Bears weight in sitting position and forms part of the pelvic outlet.

Internal Landmarks

- Linea Terminalis (Iliopectineal Line): The ridge marking the boundary between the false and true pelvis.

- Arcuate Line: The portion of the iliopectineal line on the ilium.

- Pectineal Line: The portion of the iliopectineal line on the pubis.

- Greater Sciatic Notch: Wider and more shallow in females than in males.

- Lesser Sciatic Notch: Located between the ischial spine and ischial tuberosity.

Clinical Assessment Using Pelvic Landmarks

Community health nurses use pelvic landmarks in several ways:

- Estimating Pelvic Adequacy: External measurements between landmarks (interspinous, intercristal, and intertuberous distances) can help identify potential cephalopelvic disproportion.

- Assessing Fetal Descent: During labor, fetal station is described in relation to the level of ischial spines (designated as 0 station).

- Identifying Pelvic Types: The relationship between landmarks helps classify pelvic types (gynecoid, android, anthropoid, or platypelloid).

- Pain Assessment: Tenderness at specific landmarks (e.g., symphysis pubis or sacroiliac joints) may indicate pregnancy-related pelvic disorders.

Community Health Nursing Tip:

When conducting antenatal assessments in community settings, use external pelvic landmarks to identify women who may need specialized obstetric evaluation. Teaching pregnant women to recognize their own pelvic landmarks can help them better understand the birthing process.

Pelvic Inclination

Pelvic inclination refers to the angle that the pelvis forms with the horizontal plane when a person is standing. This angle affects posture, weight distribution, and the birthing process.

Normal Pelvic Inclination

- Angle: The plane of the pelvic inlet typically forms a 55-60° angle with the horizontal plane.

- Orientation: The sacral promontory is about 9-10 cm higher than the upper border of the symphysis pubis.

- Significance: This inclination creates the forward curve in the lumbar spine (lordosis) and positions the birth canal optimally for delivery.

Pelvic Tilt

- Anterior Tilt: Increased forward inclination of the pelvis, exaggerating the lumbar lordosis.

- Posterior Tilt: Reduced forward inclination, flattening the lumbar curve.

- Lateral Tilt: One side of the pelvis is higher than the other, often associated with leg length discrepancies or scoliosis.

Factors Affecting Pelvic Inclination

- Pregnancy: The growing uterus shifts the center of gravity forward, increasing lumbar lordosis and anterior pelvic tilt.

- Body Habitus: Obesity can increase anterior pelvic tilt due to the weight of the abdomen.

- Muscular Imbalances: Tight hip flexors and weak abdominal muscles contribute to anterior pelvic tilt.

- Posture: Habitually poor posture can alter pelvic inclination over time.

- Age: Pelvic inclination may change with age due to changes in muscle tone and spinal curvature.

Clinical Significance in Community Health Nursing

- Pregnancy Discomfort: Excessive anterior pelvic tilt during pregnancy can lead to back pain.

- Labor Positioning: Pelvic inclination affects optimal positions for labor and delivery.

- Postpartum Recovery: Returning to normal pelvic alignment is important for preventing chronic back pain.

- Exercise Prescription: Exercises to correct pelvic tilt may be recommended during pregnancy and postpartum.

Community Health Education Note:

When conducting prenatal classes, teach women about pelvic tilt exercises that can help relieve back pain during pregnancy. Demonstrate how changes in pelvic position can affect comfort during labor and potentially facilitate fetal descent.

Variations in Pelvic Shape

The female pelvis exhibits several distinct morphological variations that can significantly influence childbirth outcomes. Caldwell and Moloy’s classification is widely used to describe these variations.

| Pelvic Type | Features | Inlet Shape | Obstetric Implications | Frequency in Females |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gynecoid (Female Type) |

|

Rounded or slightly oval | Ideal for childbirth; accommodates normal mechanism of labor | ~50% |

| Android (Male Type) |

|

Triangular or heart-shaped | Difficult vaginal delivery; increased risk of arrest of descent and perineal tears | ~20% |

| Anthropoid |

|

Anteroposteriorly oval | Favors occiput posterior position; may have difficult rotation during labor | ~25% |

| Platypelloid (Flat Type) |

|

Transversely oval or flattened | Difficult engagement of fetal head; may require cesarean delivery | ~5% |

Mixed Pelvic Types

Pure pelvic types are relatively uncommon. Most women have mixed pelvic morphology, combining features of different types. For example:

- Gynecoid-Anthropoid: Generally favorable for childbirth but may predispose to occiput posterior positions.

- Gynecoid-Android: May have adequate inlet but potential challenges at the midpelvis or outlet.

- Android-Anthropoid: Combines narrow subpubic arch with anteroposteriorly oval inlet, increasing complexity during delivery.

Factors Influencing Pelvic Shape

- Genetics: There is a genetic predisposition to certain pelvic types.

- Ethnicity: Some pelvic types are more common in certain ethnic groups.

- Nutrition: Early childhood nutrition affects bone development, potentially influencing pelvic shape.

- Physical Activity: Weight-bearing activities during growth years may influence pelvic development.

- Pathology: Conditions like rickets can cause pelvic deformities that affect childbirth.

Mnemonic for Pelvic Types: “GAPP”

- Gynecoid: Good for delivery (round inlet)

- Android: Awful for delivery (heart-shaped inlet)

- Platypelloid: Problematic engagement (flat inlet)

- Primate/Anthropoid: Posterior positions common (oval inlet)

Community Health Nursing Application:

While precise pelvic typing requires radiological assessment not available in community settings, community health nurses should be alert to external signs of potential pelvic variations. Women with unusual pelvic shapes may need referral for specialized assessment before labor. Additionally, understanding pelvic types helps nurses provide appropriate education about labor expectations.

Clinical Significance in Community Health

Understanding female pelvic anatomy is crucial for community health nurses who provide care across the reproductive lifespan. This knowledge informs assessment, education, and care planning in various community settings.

Antenatal Care

- Risk Assessment: Identifying women with potential pelvic inadequacy who may need specialized care.

- Maternal Positioning: Advising on positions that optimize pelvic dimensions during pregnancy and labor.

- Pelvic Pain Management: Differentiating normal pregnancy-related pelvic discomfort from pathological conditions.

- Birth Planning: Providing information on how pelvic anatomy might influence birth options and experiences.

Postpartum Care

- Pelvic Floor Recovery: Educating about pelvic floor exercises to restore function after childbirth.

- Symphysis Pubis Dysfunction: Recognizing and managing ongoing pelvic joint pain after delivery.

- Perineal Healing: Understanding pelvic floor anatomy to assess healing of episiotomy or tears.

- Posture Correction: Advising on returning to normal pelvic alignment postpartum.

Gynecological Health

- Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Identifying risk factors and providing preventive education.

- Pelvic Pain Syndromes: Differentiating potential causes based on anatomical knowledge.

- Menstrual Disorders: Understanding how pelvic anatomy relates to menstrual health.

- Contraceptive Counseling: Explaining anatomical basis for various contraceptive methods.

Health Promotion

- Pelvic Floor Exercise Education: Teaching preventive exercises across the lifespan.

- Physical Activity Guidance: Recommending activities that support pelvic health.

- Posture Education: Promoting healthy pelvic alignment to prevent pain.

- Body Awareness: Helping women understand their pelvic anatomy for better health decision-making.

Community-Based Assessment Techniques

Community health nurses rely on several non-invasive assessment techniques to evaluate pelvic health:

- External Pelvic Measurements: Measuring distances between external landmarks to estimate internal dimensions.

- Visual Assessment: Observing body habitus, posture, and gait for indications of pelvic abnormalities.

- Functional Assessment: Evaluating mobility, stability, and pain patterns related to pelvic function.

- History Taking: Gathering information about previous births, pelvic injuries, or surgeries that might affect pelvic function.

Community Health Nursing Consideration:

When providing care in resource-limited settings, community health nurses must rely on clinical skills to identify pelvic issues that require referral. Cultural sensitivity is essential when discussing pelvic health issues, as many communities have strong cultural beliefs and practices surrounding female reproductive anatomy.

Helpful Mnemonics for Female Pelvic Anatomy

Mnemonics can be valuable tools for nursing students to remember complex pelvic anatomical structures and relationships. Here are several helpful memory aids:

Pelvic Bones: “HIS”

Each hip bone (os coxae) consists of three fused bones:

- H = Hip bone (os coxae) consists of:

- I = Ilium (superior portion)

- S = combined for Ischium (posteroinferior) and Pubis (anteroinferior)

True vs. False Pelvis: “SWAP”

The difference between the true and false pelvis:

- Superior = False pelvis (above linea terminalis)

- Womb support = True pelvis (supports reproductive organs)

- Above linea terminalis = False pelvis

- Pathway for baby = True pelvis (birth canal)

Pelvic Diameters: “TAO”

Three important diameters of the pelvic inlet:

- Transverse diameter = 13.5 cm (widest)

- Anteroposterior (obstetric conjugate) = 11.5 cm

- Oblique diameter = 12.5 cm

Pelvic Ligaments: “SAIL PSA”

Major ligaments of the pelvis:

- Sacrotuberous

- Anterior sacroiliac

- Iliolumbar

- Long posterior sacroiliac

- Posterior sacroiliac

- Sacrospinous

- Arcuate pubic

Female vs. Male Pelvis: “SALE”

Key differences in the female pelvis:

- Shallow and wide (compared to deep and narrow in males)

- Angle of pubic arch >90° (vs. <70° in males)

- Lighter and less thick bones

- Extensive sacral curvature (more curved)

Pelvic Planes: “GIMME”

The sequence of pelvic planes from top to bottom:

- Greatest height = Inlet (entrance to true pelvis)

- Intermediate area = Cavity (mid-pelvis)

- Mid level = Plane of least dimensions (ischial spines)

- Minimal space = Lower pelvis

- Exit = Outlet (final plane before birth)

Visual Memory Techniques

Hand Demonstration for Pelvic Types

Use hand shapes to represent different pelvic inlet types:

- Gynecoid: Make a circle with both hands (thumbs and index fingers)

- Android: Make a triangle/heart shape with both hands

- Anthropoid: Form an oval with hands positioned vertically

- Platypelloid: Form an oval with hands positioned horizontally

Body Landmarks for Pelvic Measurements

Use your own body to remember key pelvic landmarks:

- Iliac Crests: Place hands on waist

- ASIS: Feel the anterior projections at front of pelvis

- PSIS: Feel the dimples on lower back

- Ischial Tuberosities: Feel the bones you sit on

- Pubic Symphysis: Center front of the pelvis

Learning Tip for Nursing Students:

When studying pelvic anatomy, combine these mnemonics with hands-on practice using pelvic models. Teaching these memory aids to pregnant women (using appropriate language) can help them better understand their bodies and the birthing process.

Global Perspectives and Best Practices

Different cultures and healthcare systems around the world have developed various approaches to applying knowledge of female pelvic anatomy in community health nursing practice.

Scandinavian Approach

Nordic countries emphasize preventive pelvic health education throughout the lifespan.

- Early Education: Pelvic floor awareness taught in schools

- Pregnancy Care: Routine pelvic floor assessment and training

- Postpartum: Standardized pelvic floor rehabilitation programs

- Community Integration: Pelvic health integrated into primary care

Dutch Midwifery Model

The Netherlands has developed a community-based approach that respects pelvic anatomy’s natural function.

- Risk Assessment: Detailed pelvic assessment for home birth suitability

- Positional Strategies: Various labor positions to optimize pelvic dimensions

- Community Care: Integration of home and hospital care

- Minimal Intervention: Respect for natural pelvic function during birth

Japanese Traditions

Japan blends modern medicine with traditional practices for pelvic health.

- Antenatal Binding: Traditional pelvic support techniques (Obi)

- Positional Awareness: Education on pelvic positioning

- Postpartum Recovery: Structured pelvic rehabilitation

- Dietary Considerations: Nutritional guidance for pelvic bone health

Innovative Community Health Nursing Practices

Mobile Pelvic Health Education

In rural areas of Australia and Canada, mobile health units provide pelvic health education and basic assessment to remote communities.

Key Elements:

- Portable anatomical models for education

- Telehealth connection to specialists

- Community health worker training in basic pelvic assessment

- Culturally adapted educational materials

Community-Based Pelvic Floor Programs

The United Kingdom has implemented community-based pelvic floor programs led by specialized community nurses.

Key Elements:

- Group education sessions on pelvic anatomy

- Peer support networks

- Exercise programs for pelvic floor strength

- Self-assessment tools and resources

Cultural Considerations in Pelvic Care

Community health nurses must adapt their approach to pelvic health based on cultural context:

- Language and Terminology: Developing culturally appropriate ways to discuss pelvic anatomy that respect community norms while providing accurate information.

- Gender Considerations: In many cultures, pelvic health discussions must be conducted by female providers in women-only settings.

- Traditional Practices: Integrating knowledge of beneficial traditional practices while addressing potentially harmful ones with sensitivity.

- Family Involvement: Recognizing the role of family members in reproductive health decisions in various cultures.

Global Best Practice Recommendation:

Community health nurses should combine evidence-based knowledge of pelvic anatomy with cultural humility. Successful programs adapt universal anatomical principles to local contexts, respecting traditional knowledge while providing accurate information. The most effective approach integrates pelvic health education throughout the lifespan rather than focusing only on pregnancy and childbirth.