Fetal Skull & Fetopelvic Relationship

Comprehensive Nursing Notes

Introduction

Understanding the fetal skull anatomy and its relationship with the maternal pelvis is fundamental in obstetric nursing practice. The fetal cranium is uniquely designed to facilitate the birth process, with its adaptable structure allowing passage through the birth canal. This comprehensive guide explores the fetal skull anatomy, including bones, sutures, fontanelles, diameters, and moulding, as well as the critical fetopelvic relationship that determines the course of labor and delivery.

The fetal cranium differs significantly from the adult skull, with specialized features that accommodate both brain growth and the birth process. These adaptations include unfused bones connected by fibrous sutures and fontanelles (soft spots), which provide flexibility during delivery while protecting the developing brain.

Important Note: The adaptability of the fetal cranium is a crucial factor in successful vaginal delivery. The interplay between fetal skull features and maternal pelvic dimensions determines the ease or difficulty of the birthing process.

Fetal Skull Anatomy

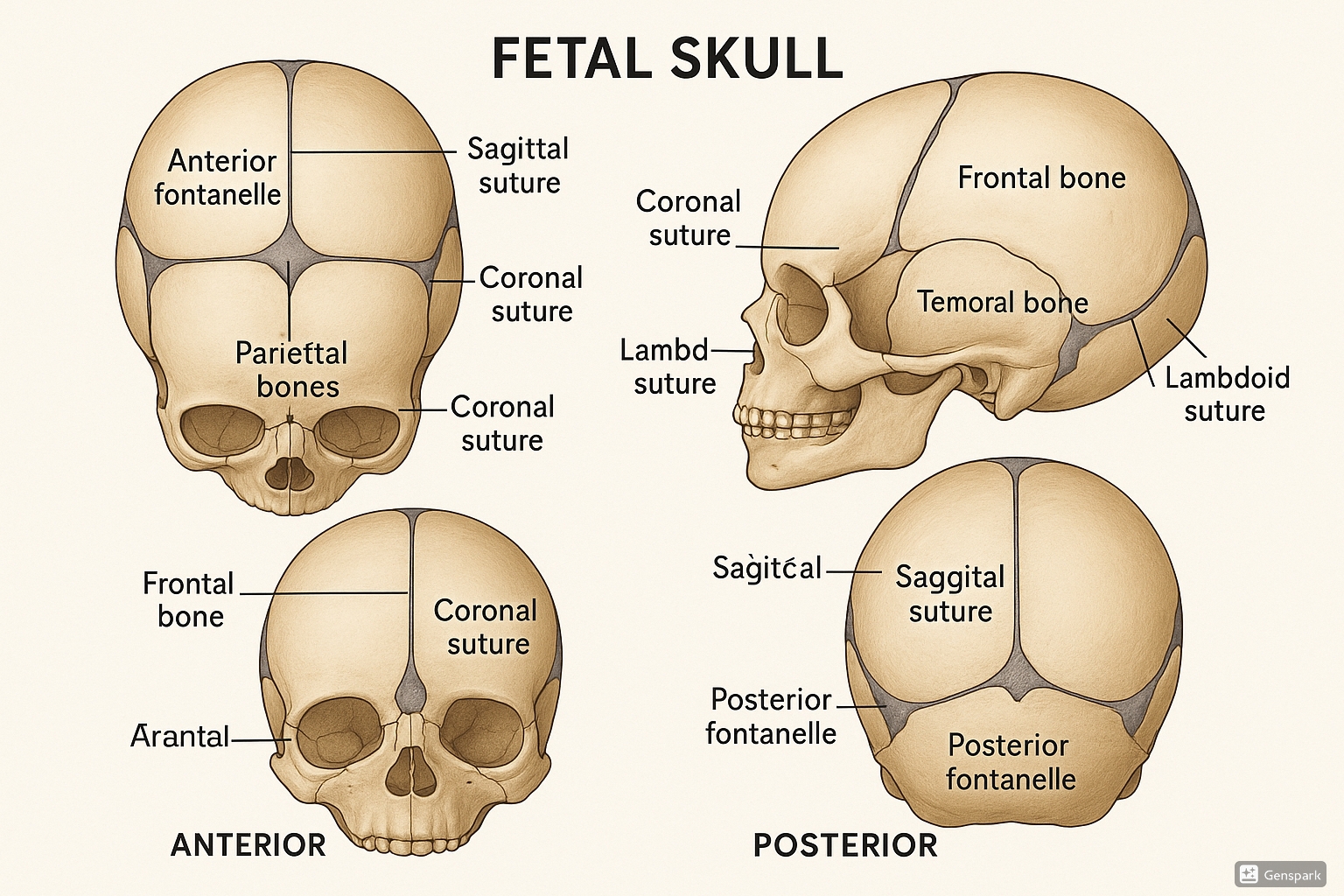

The fetal skull or cranium consists of the vault (calvarium), face, and base. The vault protects the brain and is composed of several bones connected by sutures. The unique structure of these components allows for the flexibility needed during delivery while maintaining protection for the developing brain.

Figure 1: Detailed anatomy of the fetal skull showing bones, sutures, and fontanelles.

Bones of the Fetal Skull

The fetal cranium consists of several bones that are not fully fused at birth, allowing for flexibility during delivery. These bones include:

| Bone | Quantity | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Frontal Bones | 2 | Form the forehead and the anterior part of the cranium; separated by the frontal suture at birth. |

| Parietal Bones | 2 | Form the roof and sides of the cranium; separated by the sagittal suture. |

| Occipital Bone | 1 | Forms the posterior part of the cranium and the base of the skull. |

| Temporal Bones | 2 | Form the lower sides of the cranium and house the ear structures. |

| Sphenoid Bone | 1 | Butterfly-shaped bone at the base of the cranium. |

Mnemonic: “FOSTER” for Fetal Skull Bones

- Frontal bones (2) – Forming forehead

- Occipital bone (1) – Occupying back

- Sphenoid bone (1) – Situated centrally

- Temporal bones (2) – Taking sides

- Ethmoid bone (1) – Enclosed in nasal cavity

- Roof formed by parietal bones (2)

Sutures of the Fetal Skull

Sutures are fibrous joints that connect the bones of the cranium. They allow for slight movement during birth and accommodate brain growth in infancy. The principal sutures of obstetric importance include:

| Suture | Location | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Sagittal Suture | Runs anteroposteriorly between the two parietal bones | Helps determine fetal position during labor; connects anterior and posterior fontanelles |

| Coronal Suture | Runs transversely between the frontal and parietal bones | Forms part of the boundary of the anterior fontanelle |

| Lambdoid Suture | Runs transversely between the occipital and parietal bones | Forms part of the posterior fontanelle; important for moulding |

| Frontal Suture | Runs anteroposteriorly between the two frontal bones | Usually closes by 8 years of age; contributes to moulding |

During vaginal delivery, these sutures allow for significant overlap of cranium bones, facilitating passage through the birth canal. This process is known as moulding and is essential for a successful vaginal delivery.

Fontanelles of the Fetal Skull

Fontanelles are membrane-covered spaces where multiple skull bones meet but have not yet fused. These “soft spots” on the fetal cranium are critical for both the birth process and early brain development.

| Fontanelle | Location | Shape | Closure Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior Fontanelle | Junction of sagittal, coronal, and frontal sutures | Diamond-shaped; 2-3 cm wide and 3-4 cm long | 18-24 months after birth |

| Posterior Fontanelle | Junction of sagittal and lambdoid sutures | Triangular; smaller than anterior | 1-2 months after birth |

| Sphenoid (Anterolateral) Fontanelle | Junction of frontal, parietal, temporal, and sphenoid bones | Irregular | 6 months after birth |

| Mastoid (Posterolateral) Fontanelle | Junction of parietal, temporal, and occipital bones | Irregular | 6-18 months after birth |

Clinical Assessment of Fontanelles

Fontanelles provide valuable clinical information about a newborn’s health status:

- Bulging fontanelle: May indicate increased intracranial pressure (hydrocephalus, meningitis)

- Sunken fontanelle: May indicate dehydration

- Delayed closure: May indicate hypothyroidism, rickets, or other developmental issues

- Premature closure: May indicate microcephaly or craniosynostosis

Mnemonic: “ABCD” for Fontanelle Assessment

- Anterior – Diamond-shaped, closes by 2 years

- Back (Posterior) – Triangle-shaped, closes by 2 months

- Corners have Sphenoid fontanelles – Close by 6 months

- Down back has Mastoid fontanelles – Close by 18 months

Diameters of the Fetal Skull

The dimensions of the fetal cranium are crucial in determining whether vaginal delivery is possible. These measurements must be compared with the dimensions of the maternal pelvis to assess whether there is adequate space for the fetus to pass through the birth canal.

Anteroposterior Diameters

These diameters run from front to back of the fetal cranium and are significant in different presentations:

| Diameter | Measurement | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suboccipitobregmatic | 9.5 cm | From the undersurface of the occipital bone to the center of the anterior fontanelle | Presents in well-flexed head (vertex presentation) |

| Occipitofrontal | 11.5 cm | From the external occipital protuberance to the most prominent point of the frontal bone | Presents in moderate deflexion (sinciput presentation) |

| Occipitomental | 12.5 cm | From the external occipital protuberance to the chin | Presents in face presentation |

| Submentobregmatic | 9.5 cm | From the junction of the neck and mandible to the center of the anterior fontanelle | Presents in complete extension (face presentation) |

Transverse Diameters

These diameters run from side to side across the fetal cranium:

| Diameter | Measurement | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biparietal | 9.5 cm | Between the parietal eminences (widest transverse diameter) | Most important for assessment of engagement |

| Bitemporal | 8.2 cm | Between the widest points of the temporal bones | Smaller than biparietal, important in deflexed head |

| Bimastoid | 7.5 cm | Between the mastoid processes | Smallest transverse diameter, less clinical relevance |

The biparietal diameter is typically used to measure fetal head size on ultrasound. When this diameter passes through the pelvic inlet, the fetal head is considered to be engaged in the pelvis.

Vertical Diameters

These diameters run from top to bottom of the fetal cranium:

| Diameter | Measurement | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verticomental | 13.5 cm | From the vertex to the chin | Largest diameter, presents in brow presentation |

| Vertico-suboccipital | 9.8 cm | From the highest point of the vertex to the undersurface of the occipital bone | Important in certain deflexed presentations |

Mnemonic: “SOFA BVV” for Fetal Skull Diameters

- Suboccipitobregmatic – 9.5 cm (Smallest AP)

- Occipitofrontal – 11.5 cm (Medium AP)

- Face to occiput (Occipitomental) – 12.5 cm (Larger AP)

- Across the skull: Biparietal – 9.5 cm (Largest transverse)

- Verticomental – 13.5 cm (Largest overall)

- Vertico-suboccipital – 9.8 cm (Vertical)

Moulding of the Fetal Skull

Moulding is the process by which the shape of the fetal cranium changes during labor to accommodate the dimensions and shape of the maternal pelvis. This process is facilitated by the presence of sutures and fontanelles, which allow the cranial bones to overlap slightly.

The Moulding Process

During labor, uterine contractions push the fetal head against the cervix and pelvis. The pressure causes the bones of the cranium to shift position relative to one another at the suture lines. This adaptation reduces the presenting diameter of the fetal head, facilitating passage through the birth canal.

The degree of moulding possible depends on:

- The elasticity of the sutures

- The size of the fontanelles

- The strength and duration of uterine contractions

- The resistance offered by the maternal pelvis

Types of Moulding

Moulding is classified based on the degree of overlap between the cranium bones:

| Grade | Description | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Sutures are apart, bones separated, can be felt easily | No moulding; early labor or no engagement |

| +1 | Bones are touching with no overlap | Minimal moulding; early active labor |

| +2 | Bones overlapping but can be reduced with gentle pressure | Moderate moulding; active labor |

| +3 | Bones overlapping and cannot be reduced | Severe moulding; may indicate cephalopelvic disproportion |

Common Patterns of Moulding

- Occipito-anterior position: Frontal bones slide under parietal bones, and occipital bone slides under both parietal bones, creating an elongated, oval-shaped head

- Occipito-posterior position: Occipital bone overrides the parietal bones, creating a more rounded head shape

- Asynclitism: Uneven moulding where one parietal bone overrides more than the other

Clinical Significance of Moulding

Assessment of cranium moulding provides valuable information about the progress of labor and potential complications:

- Minimal moulding: Normal finding in early labor

- Progressive moulding: Generally indicates good progress with adequate pelvic dimensions

- Excessive moulding (Grade +3): May suggest cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD) or obstruction

- Persistent moulding after birth: Usually resolves within 24-72 hours; prolonged moulding may indicate birth trauma

Excessive moulding can lead to:

- Increased intracranial pressure

- Compression of cerebral vessels

- Dural tears

- Tentorial tears

- Intracranial hemorrhage

Therefore, monitoring the degree of moulding is an essential part of intrapartum assessment.

Fetopelvic Relationship

The fetopelvic relationship describes how the fetus is positioned within the maternal pelvis. This relationship is critical for determining the course of labor and potential complications. A thorough understanding of these concepts helps nurses anticipate the progress of labor and identify potential complications early.

Fetal Lie

Fetal lie refers to the relationship between the long axis (spine) of the fetus and the long axis (spine) of the mother.

| Type | Description | Incidence | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal | Fetal spine parallel to maternal spine | 99% at term | Normal; allows for vaginal delivery |

| Transverse | Fetal spine perpendicular to maternal spine | <1% at term | Abnormal at term; requires cesarean delivery |

| Oblique | Fetal spine at an angle to maternal spine | Rare at term | Usually converts to longitudinal or transverse during labor |

Fetal Presentation

Presentation refers to the part of the fetus that is entering the pelvis first and will be the first to be delivered.

| Presentation | Description | Incidence | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cephalic | Head/Cranium presenting first | 96% at term | Normal; most favorable for vaginal delivery |

| Breech | Buttocks or feet presenting first | 3-4% at term | Higher risk; may require cesarean delivery |

| Shoulder (Transverse) | Shoulder presenting first | <1% at term | Cannot deliver vaginally; requires cesarean |

| Compound | Two parts presenting simultaneously (e.g., hand and head) | Very rare | May require intervention |

Types of Cephalic Presentation

- Vertex: Well-flexed head, occiput presenting (most common)

- Sinciput: Partially deflexed head, anterior fontanelle presenting

- Brow: Moderately deflexed head, forehead presenting

- Face: Fully deflexed head, face presenting

Types of Breech Presentation

- Complete: Buttocks presenting with flexed hips and knees

- Frank: Buttocks presenting with flexed hips and extended knees

- Footling: One or both feet presenting

- Kneeling: One or both knees presenting (rare)

Mnemonic: “CABS” for Fetal Presentations

- Cephalic – 96% (Cranium first, most common)

- Anatomical variants of cephalic (Vertex, Sinciput, Brow, Face)

- Breech – 3-4% (Bottom first, higher risk)

- Shoulder – <1% (Side/transverse, needs C-section)

Fetal Position

Position refers to the relationship between a specific reference point on the presenting part of the fetus and the maternal pelvis. For cephalic presentations, the reference point is the occiput (back of the head).

| Position | Abbreviation | Description | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Occiput Anterior | OA | Occiput points toward mother’s front | Most favorable for delivery |

| Right Occiput Anterior | ROA | Occiput points to mother’s front-right | Favorable |

| Left Occiput Anterior | LOA | Occiput points to mother’s front-left | Favorable |

| Occiput Posterior | OP | Occiput points toward mother’s back | May cause prolonged labor, back pain |

| Right Occiput Posterior | ROP | Occiput points to mother’s back-right | May be more difficult |

| Left Occiput Posterior | LOP | Occiput points to mother’s back-left | May be more difficult |

| Right Occiput Transverse | ROT | Occiput points to mother’s right side | Should rotate to anterior or posterior |

| Left Occiput Transverse | LOT | Occiput points to mother’s left side | Should rotate to anterior or posterior |

Occiput posterior positions are associated with:

- Prolonged labor

- Increased back pain

- Higher rates of instrumental delivery

- Increased perineal trauma

- Higher cesarean section rates

Fetal Attitude

Attitude refers to the relationship between the fetal parts, particularly the degree of flexion or extension of the head and limbs.

| Attitude | Description | Presenting Diameter | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete Flexion | Chin touching chest | Suboccipitobregmatic (9.5 cm) | Most favorable; vertex presentation |

| Partial Deflexion | Chin away from chest | Occipitofrontal (11.5 cm) | Less favorable; sinciput presentation |

| Moderate Deflexion | Head halfway extended | Intermediate (12 cm) | Unfavorable; brow presentation |

| Complete Deflexion | Head fully extended | Submentobregmatic (9.5 cm) | Less favorable; face presentation |

Engagement and Descent

Engagement refers to the entry of the largest diameter of the presenting part (usually the biparietal diameter of the cranium) into the true pelvis.

Assessment of Engagement

Engagement is assessed by determining the relationship between the presenting part and the ischial spines (station):

- Station: Measured in centimeters, from -5 to +5

- 0 station: Presenting part at the level of ischial spines

- Negative stations (-1 to -5): Presenting part above the ischial spines

- Positive stations (+1 to +5): Presenting part below the ischial spines

- Engagement: Typically occurs when the presenting part is at station 0 or lower

Clinical Implications of Engagement

- In first-time mothers (nulliparas), engagement often occurs before labor begins

- In women who have given birth before (multiparas), engagement may not occur until labor begins

- Failure to engage may indicate cephalopelvic disproportion, abnormal presentation, or placenta previa

Clinical Implications

Understanding the fetal skull anatomy and fetopelvic relationship is essential for nurses caring for laboring women. This knowledge allows for early identification of potential complications and appropriate interventions.

Cephalopelvic Disproportion (CPD)

CPD occurs when the fetal head is too large to pass through the maternal pelvis. Signs include:

- Failure of the presenting part to engage

- Excessive moulding

- Arrested labor progress despite adequate contractions

- Formation of significant caput succedaneum

Management typically involves cesarean delivery.

Caput Succedaneum vs. Cephalhematoma

Caput Succedaneum: Edema of the scalp tissue that crosses suture lines, develops during labor due to pressure against the cervix, usually resolves within 24-48 hours.

Cephalhematoma: Subperiosteal hemorrhage that does not cross suture lines, may develop after delivery, can take weeks to resolve and may lead to hyperbilirubinemia.

Persistent Occiput Posterior Position

When the fetus remains in occiput posterior position throughout labor, the following interventions may be helpful:

- Maternal position changes (hands and knees, pelvic tilts)

- Adequate analgesia for back pain

- Potential for instrumental rotation or cesarean delivery if progress is inadequate

Nursing Assessments During Labor

- Palpate fontanelles and sutures to determine position and degree of moulding

- Monitor the station and descent of the presenting part

- Assess fetal heart rate in relation to maternal pelvis (best heard over fetal back)

- Document findings accurately to track progress over time

Conclusion

The fetal cranium is a marvel of evolutionary design, with its specialized structure facilitating both brain development and the birth process. Understanding the intricacies of fetal skull anatomy—its bones, sutures, fontanelles, diameters, and moulding capacity—as well as the fetopelvic relationship is essential for nursing professionals attending births.

This knowledge enables nurses to:

- Anticipate normal labor progress

- Identify potential complications early

- Support evidence-based interventions

- Communicate effectively with the healthcare team

- Provide informed support to laboring women

By mastering these concepts, nurses can significantly contribute to positive birth outcomes and enhance the safety and experience of childbirth for mothers and babies alike.

Global Best Practices

Many countries have implemented evidence-based practices related to the assessment and management of fetopelvic relationships:

- Sweden: Emphasizes hands-on training for midwives in assessing fetal position through abdominal palpation and vaginal examination, reducing the need for ultrasound during labor.

- Netherlands: Incorporates maternal positioning techniques to optimize fetal position before and during labor, particularly for occiput posterior positions.

- Japan: Uses specialized maternal postures during pregnancy to encourage optimal fetal positioning prior to labor onset.

- United Kingdom: National guidelines recommend regular assessment of fetal position and station during labor as part of routine monitoring.

- Australia: Has developed specific education programs for parents about fetal positioning and its impact on labor progress.

References

- Anatomy, Head and Neck: Fontanelles – StatPearls. (2023). NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542197/

- Anatomy of the Newborn Skull. Stanford Medicine Children’s Health. https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=anatomy-of-the-newborn-skull-90-P01840

- Fetal skull vault sutures. Radiology Reference Article. Radiopaedia. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/fetal-skull-vault-sutures?lang=us

- Foetal Skull. D. El-Mowafi. https://www.gfmer.ch/Obstetrics_simplified/foetal_skull.htm

- Fetal head molding. MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/imagepages/17176.htm

- Configuration (molding) of the fetal head during labor and related issues. OAText. https://www.oatext.com/configuration-molding-of-the-fetal-head-during-labor-and-related-issues.php

- Fetopelvic Relationships. Oxorn-Foote Human Labor & Birth, 6e. https://obgyn.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=1247§ionid=75161617