Management of Dysphagia and Dyspepsia: Community Health Nursing Perspectives

A Comprehensive Guide on Screening, Diagnosis, Primary Care, and Referral

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

In community health nursing, the effective management of common conditions and emergencies is crucial for providing quality care and preventing complications. This comprehensive guide focuses on two prevalent conditions encountered in community settings: dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and dyspepsia (indigestion). Both conditions significantly impact patients’ quality of life and nutritional status, making their proper management essential for community health nurses.

Key Point: Dysphagia and dyspepsia are common in community settings, particularly among elderly populations. According to studies, dysphagia affects up to 22% of adults over 50 years and up to 70% of nursing home residents. Dyspepsia affects approximately 25% of the general population.

This guide provides a structured approach to screening, diagnosis, primary care, and referral criteria for both conditions, with practical tools and mnemonics to assist community health nurses in their daily practice. The guide also covers standing orders and first aid protocols that can be implemented in community settings.

2. Standing Orders: Definition and Uses

Definition of Standing Orders

Standing orders are written protocols that authorize designated members of the healthcare team (e.g., nurses or medical assistants) to complete certain clinical tasks without having to first obtain a physician order. They provide a standardized approach to care while optimizing workflow and expanding the scope of practice for nursing professionals.

Key Components of Standing Orders

Standing orders typically include the following elements:

- Specific clinical conditions or situations when the order applies

- Clear criteria for identifying eligible patients

- Detailed instructions for assessment and intervention

- Documentation requirements

- Parameters for physician notification or consultation

- Timeframes for intervention and follow-up

Uses of Standing Orders in Community Health Nursing

| Area of Application | Examples for Dysphagia | Examples for Dyspepsia |

|---|---|---|

| Screening | Authorization to conduct standardized swallowing assessments for at-risk patients | Protocol for screening patients with recurrent digestive symptoms |

| Emergency Management | Steps for managing choking or aspiration emergencies | Management of acute indigestion with appropriate medications |

| Preventive Care | Dietary modifications and positioning techniques for at-risk patients | Lifestyle modification counseling for patients with recurring dyspepsia |

| Diagnostic Testing | Authorization to order swallowing studies or refer to specialists | Protocol for ordering H. pylori testing or endoscopy referrals |

| Follow-up Care | Schedule for reassessment of swallowing function | Follow-up assessment after medication initiation |

Benefits of Standing Orders

Advantages of Using Standing Orders in Community Settings

- Improved efficiency and timely care delivery

- Enhanced role utilization for nursing professionals

- Standardized approach to common conditions

- Reduced burden on physicians

- Improved patient outcomes through early intervention

- Decreased hospitalization rates through prompt community management

Important: Standing orders must be dated, signed by the authorizing physician, and reviewed regularly. They should comply with state nurse practice acts and institutional policies. Community health nurses must be properly trained in the implementation of standing orders and understand when physician consultation is necessary.

3. Dysphagia

3.1 Definition and Pathophysiology

Dysphagia refers to difficulty in swallowing and is characterized by the impaired passage of food or liquid from the mouth to the stomach. It is a symptom rather than a disease and can occur at any age, though it is more common in older adults and those with neurological conditions.

Types of Dysphagia

| Type | Description | Common Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Oropharyngeal Dysphagia | Difficulty initiating swallowing; problems transferring food from mouth to esophagus | Neurological disorders (stroke, Parkinson’s), muscle disorders, structural abnormalities |

| Esophageal Dysphagia | Sensation of food sticking in the throat or chest after swallowing has begun | Mechanical obstruction, motility disorders, GERD, esophageal strictures |

The swallowing process involves a complex coordination of nerves and muscles through four main phases:

- Oral Preparatory Phase: Food is manipulated and masticated in preparation for swallowing

- Oral Phase: The tongue propels the bolus of food to the back of the mouth

- Pharyngeal Phase: Swallowing reflex is triggered; food passes through the pharynx

- Esophageal Phase: Food is transported through the esophagus to the stomach

Disruption in any of these phases can result in swallowing disorders and related complications.

3.2 Causes and Risk Factors

Mnemonic: “SWALLOWING”

Common causes and risk factors for dysphagia can be remembered with this mnemonic:

High-Risk Populations

- Elderly individuals (age-related changes in swallowing mechanism)

- Stroke survivors (up to 65% experience dysphagia)

- Patients with neurodegenerative diseases

- Individuals with head and neck cancer or who have undergone related treatments

- Patients with tracheostomy or who are on mechanical ventilation

- Those with cognitive impairments affecting self-feeding

Community Health Perspective: In community settings, it’s essential to identify at-risk individuals early, as dysphagia can lead to serious complications including aspiration pneumonia, dehydration, malnutrition, and decreased quality of life. Community health nurses are often the first to identify swallowing disorders in homebound patients or during routine assessments.

3.3 Screening and Assessment

Early identification of dysphagia through screening is crucial for preventing complications. Community health nurses should incorporate swallowing assessment into routine evaluations, particularly for high-risk patients.

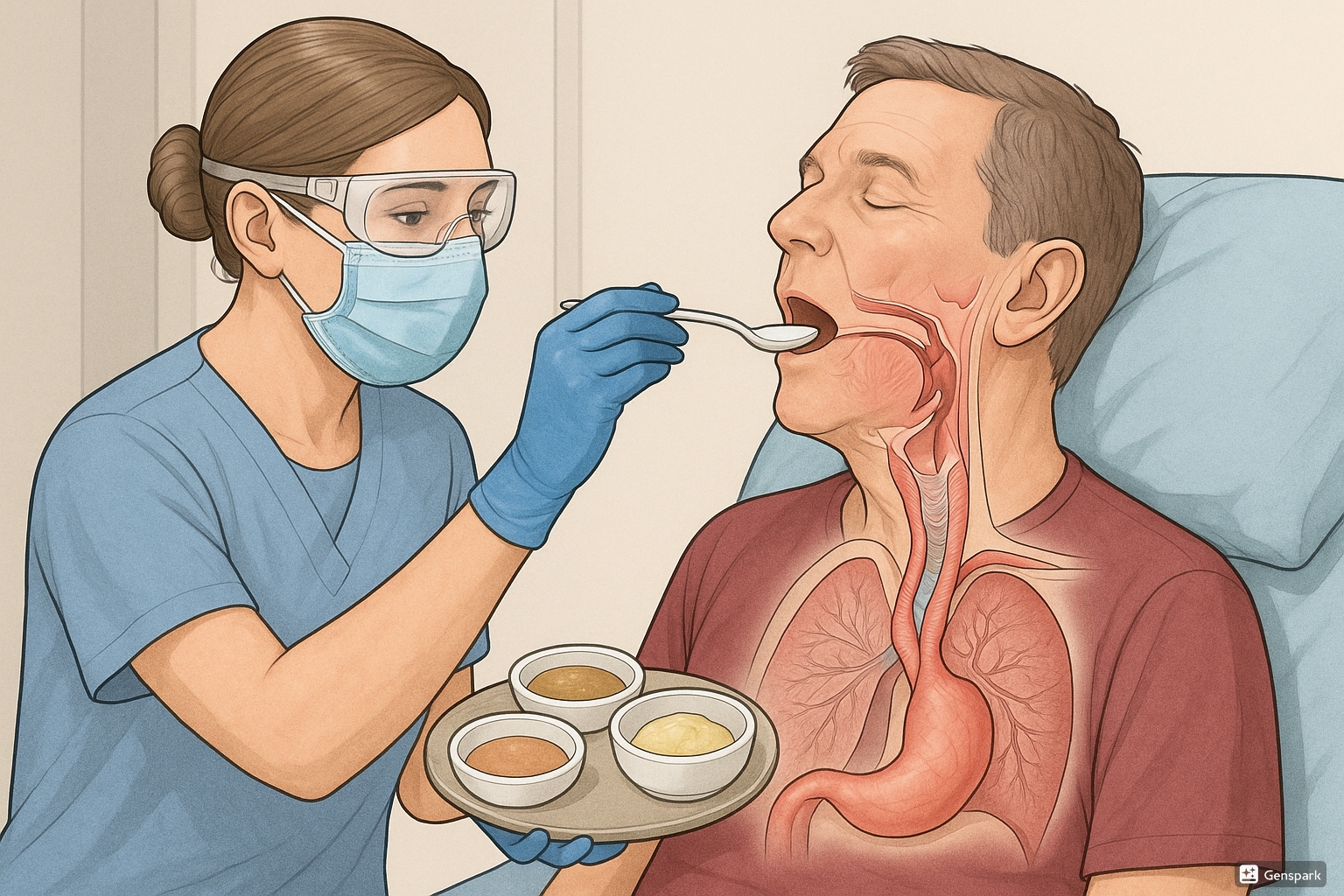

Clinical illustration of dysphagia assessment showing proper positioning and evaluation techniques.

Screening Tools for Dysphagia

| Screening Tool | Description | Application in Community Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Water Swallow Test | Patient is asked to swallow small amounts of water; observer monitors for coughing, choking, voice changes, or delayed swallowing | Quick, non-invasive; easily performed during home visits |

| Toronto Bedside Swallowing Screening Test (TOR-BSST) | Assesses voice quality, tongue movement, water swallow test | Structured approach with good sensitivity and specificity |

| Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) | 10-item questionnaire assessing perceived swallowing difficulties | Self-administered; good for initial screening |

| 4-Finger Test | Palpation technique to assess hyoid and laryngeal movement during swallowing | Can be performed without special equipment |

| GUSS (Gugging Swallowing Screen) | Progressive assessment from saliva swallowing to semi-solid and liquid foods | More comprehensive; suitable for stroke patients |

Mnemonic: “PASS” for Dysphagia Screening

A quick bedside assessment approach:

Key Observations During Assessment

- Coughing, choking, or throat clearing during or after swallowing

- Wet or “gurgly” voice quality after swallowing

- Food remaining in the mouth after swallowing

- Multiple swallows needed for a single bolus

- Delayed swallow initiation

- Nasal regurgitation

- Drooling or poor lip closure

- Weight loss or signs of dehydration

- Recurrent respiratory infections (potential sign of aspiration)

- Meal avoidance or prolonged feeding times

Warning Signs Requiring Immediate Attention:

- Acute onset of dysphagia

- Complete inability to swallow

- Signs of airway compromise

- Severe coughing episodes with attempted swallowing

- Significant weight loss or dehydration

3.4 Diagnosis

While screening by community health nurses can identify potential swallowing disorders, definitive diagnosis typically requires specialized assessments:

Diagnostic Tests for Dysphagia

| Diagnostic Test | Description | Information Provided |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Bedside Examination | Comprehensive evaluation by speech-language pathologist | Initial assessment of swallowing phases, oral motor function |

| Videofluoroscopic Swallow Study (VFSS) | X-ray visualization of swallowing using barium contrast | Gold standard; visualizes all phases of swallowing |

| Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES) | Endoscopic examination of swallowing function | Direct visualization of pharyngeal swallowing and aspiration |

| Esophageal Manometry | Measures pressure and timing of esophageal contractions | Evaluates esophageal motility disorders |

| Pharyngeal pH Monitoring | Measures acid reflux into pharynx | Identifies reflux as potential cause of dysphagia |

Diagnostic Criteria

Diagnosis of dysphagia is based on:

- Clinical presentation and history

- Physical examination findings

- Results of specialized swallowing assessments

- Identification of underlying causes

Community Health Nursing Role: The community health nurse plays a vital role in:

- Recognizing the need for diagnostic testing

- Facilitating referrals to appropriate specialists

- Ensuring follow-through with diagnostic appointments

- Communicating findings to the healthcare team

- Implementing recommendations in the home setting

3.5 Management and Primary Care

Management of dysphagia in community settings focuses on:

- Ensuring safe swallowing and adequate nutrition

- Preventing complications, especially aspiration pneumonia

- Addressing underlying causes when possible

- Improving quality of life

- Supporting caregivers with proper techniques

Dietary Modifications

| Food/Liquid Consistency | Description | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Regular | Normal food, no modifications | Mild dysphagia with intact swallowing safety |

| Soft | Moisture-rich foods that form a cohesive bolus | Mild chewing difficulties |

| Minced & Moist | Soft, small (4mm) particles that require minimal chewing | Moderate chewing difficulties |

| Pureed | Smooth, lump-free consistency | Severe chewing difficulties; reduced tongue control |

| Liquidized | Drinkable consistency, pours like a thin shake | Very limited oral skills but intact swallow reflex |

| Thickened Liquids | Nectar, honey, or pudding thickness | Delayed swallow trigger; poor airway protection |

Swallowing Techniques and Positioning

Community health nurses can teach the following compensation strategies:

- Chin Tuck: Tucking the chin toward the chest while swallowing

- Head Turn: Turning the head toward the weaker side

- Supraglottic Swallow: Holding breath while swallowing, then coughing

- Effortful Swallow: Consciously contracting muscles more forcefully during swallowing

- Multiple Swallows: Using several swallows to clear a single bolus

- Alternate Liquids and Solids: Alternating bites to clear the pharynx

Positioning for Safe Swallowing

- Upright position (90 degrees) whenever possible

- Proper head alignment, neutral or slightly flexed forward

- Feet flat on floor or supported

- Maintain position for 30 minutes after meals

- For bedridden patients, elevate head of bed to at least 30 degrees

Oral Hygiene

Meticulous oral hygiene is essential to reduce bacterial load and minimize aspiration pneumonia risk:

- Regular brushing of teeth, gums, tongue, and palate

- Use of antimicrobial mouthwash

- Denture cleaning and removal at night

- Moisturizing of dry mouth

- Checking for and removing food residue after meals

Rehabilitation Exercises

The community health nurse can teach and monitor these exercises when recommended by a speech-language pathologist:

- Shaker Exercise: Strengthens suprahyoid muscles

- Tongue Strengthening: Improves tongue propulsion

- Masako Maneuver: Enhances posterior pharyngeal wall movement

- Vocal Exercises: Improves laryngeal elevation and protection

- Thermal-Tactile Stimulation: Increases sensory awareness

Nutritional Considerations

- Monitor weight and hydration status regularly

- Ensure adequate caloric and protein intake despite dietary modifications

- Consider nutritional supplements if intake is inadequate

- Maintain food diary to track intake and identify problematic foods

- Schedule more frequent, smaller meals if fatigue is an issue

- Ensure proper positioning during and after meals

Alternative Feeding Methods

In severe cases, alternative feeding methods may be necessary:

- Nasogastric (NG) Tube: Short-term feeding solution

- Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (PEG): Long-term enteral feeding

- Jejunostomy Tube: Used when gastric feeding is contraindicated

Community Health Nursing Role: As a community health nurse, your responsibilities include:

- Implementing and monitoring dysphagia management plans

- Training caregivers in safe feeding techniques

- Monitoring for complications and progress

- Adjusting interventions based on patient response

- Coordinating with the multidisciplinary team

- Providing emotional support to patients and caregivers

3.6 First Aid for Choking and Aspiration

Community health nurses must be prepared to manage choking emergencies, which are a serious complication of dysphagia. Additionally, they should teach these techniques to caregivers and family members.

Recognizing Choking:

- Universal choking sign (hands clutching throat)

- Inability to speak or breathe

- Weak, ineffective cough or no cough at all

- High-pitched wheezing or no sounds while breathing

- Blue or dusky skin, lips, and nail beds

- Loss of consciousness if not relieved

First Aid for Conscious Choking Adult or Child (Over 1 Year)

Assess the Situation – Determine if the person can speak, cough, or breathe. If they cannot, proceed with intervention.

Back Blows – Stand to the side and slightly behind the choking person. Support their chest with one hand and lean them forward. Deliver 5 sharp blows between the shoulder blades with the heel of your hand.

Abdominal Thrusts (Heimlich Maneuver) – If back blows are ineffective, stand behind the person with your arms around their waist. Place your fist with the thumb side against the middle of their abdomen, just above the navel. Grasp your fist with your other hand and press inward and upward with quick jerks. Perform 5 abdominal thrusts.

Alternate and Repeat – Continue alternating between 5 back blows and 5 abdominal thrusts until the object is dislodged or the person becomes unconscious.

If Person Becomes Unconscious – Lower the person carefully to the ground and call for emergency assistance. Begin CPR, starting with chest compressions. Before giving rescue breaths, look in the mouth for the obstructing object and remove it if visible.

Modifications for Special Populations

- Pregnant or Obese Individuals: Chest thrusts instead of abdominal thrusts

- Self-Administration: Self-administered abdominal thrusts against a firm object like a chair back

- Bedridden Patients: Modified approach with patient in side-lying position

Managing Aspiration

If aspiration is suspected but the airway is not completely obstructed:

- Stop oral intake immediately

- Position the person in an upright position, leaning slightly forward

- Encourage coughing to clear the airway

- Monitor for signs of respiratory distress or pneumonia

- Seek medical attention promptly

- Document the incident and follow-up care

Aspiration Pneumonia Warning Signs: Following an aspiration event, monitor for:

- Fever developing within 24-48 hours

- Increased respiratory rate or difficulty breathing

- Decreased oxygen saturation

- Productive cough, possibly with foul-smelling sputum

- Chest pain

- Fatigue and general malaise

3.7 Referral Criteria

Community health nurses should refer patients with dysphagia to specialists based on the following criteria:

Urgent Referral Indications

- Sudden onset of dysphagia

- Complete inability to swallow (including saliva)

- Significant aspiration events

- Progressive worsening of swallowing function

- Unexplained weight loss (>5% in one month or >10% in six months)

- Signs of dehydration or malnutrition

- Recurrent aspiration pneumonia

Specialist Referrals

| Specialist | Indications for Referral | Services Provided |

|---|---|---|

| Speech-Language Pathologist | Any confirmed or suspected dysphagia | Comprehensive swallowing assessment, therapy, and rehabilitation |

| Gastroenterologist | Suspected esophageal dysphagia, GERD, or other GI causes | Endoscopy, motility studies, dilation procedures |

| Neurologist | Suspected neurological cause of dysphagia | Neurological assessment and management |

| ENT Specialist | Suspected structural abnormalities in throat or upper airway | Laryngoscopy, surgical interventions |

| Dietitian | Nutritional concerns, weight loss, specialized diet needs | Nutritional assessment and management |

| Occupational Therapist | Need for adaptive feeding equipment or positioning | Assistive devices, feeding strategies |

Information to Include in Referrals

- Detailed description of swallowing difficulties

- Onset and progression of symptoms

- Results of any screening tests performed

- Current diet modifications and effectiveness

- Relevant medical history

- Current medications

- Weight trends

- History of aspiration or pneumonia

- Impact on quality of life and daily functioning

Follow-up After Referral: The community health nurse should:

- Ensure the patient attends specialist appointments

- Implement recommendations from specialists

- Monitor the patient’s progress with the treatment plan

- Maintain communication with the healthcare team

- Provide ongoing education and support to the patient and caregivers

4. Dyspepsia

4.1 Definition and Pathophysiology

Dyspepsia, commonly known as indigestion, refers to persistent or recurrent pain or discomfort centered in the upper abdomen. It is a symptom complex rather than a specific disease and affects approximately 25% of the general population.

Types of Dyspepsia

| Type | Description | Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Organic Dyspepsia | Identifiable structural or biochemical cause | Peptic ulcer, GERD, gastritis, gallstones, pancreatic disorders, medications, malignancy |

| Functional Dyspepsia | No identifiable structural or biochemical cause despite appropriate investigation | Altered gut motility, visceral hypersensitivity, psychosocial factors, altered gut microbiota |

Subtypes of Functional Dyspepsia (Rome IV Criteria)

- Postprandial Distress Syndrome (PDS): Meal-induced digestive discomfort and early satiation

- Epigastric Pain Syndrome (EPS): Epigastric pain or burning not exclusively postprandial

- Overlap: Many patients exhibit features of both subtypes

Pathophysiological Mechanisms

- Delayed Gastric Emptying: More common in PDS, leads to prolonged gastric distention

- Impaired Gastric Accommodation: Reduced relaxation of proximal stomach after meals

- Visceral Hypersensitivity: Increased perception of normal gastric sensations

- Altered Duodenal Sensitivity: Heightened sensitivity to acids and lipids

- Inflammation: Low-grade mucosal inflammation in some cases

- Helicobacter pylori Infection: Can cause dyspepsia in a subset of patients

- Psychosocial Factors: Anxiety, depression, stress can exacerbate symptoms

Key Point: Dyspepsia is not just “heartburn” or GERD, although there is significant overlap. Digestive discomfort in dyspepsia is centered in the epigastrium rather than retrosternally, and includes a broader symptom complex beyond acid regurgitation.

4.2 Causes and Risk Factors

Mnemonic: “DIGESTIVE”

Common causes and risk factors for dyspepsia:

Risk Factors for Dyspepsia

- Demographic Factors:

- Female gender (more common in functional dyspepsia)

- Advanced age (increased risk of organic causes)

- Family history of gastrointestinal disorders

- Lifestyle Factors:

- Smoking

- Excessive alcohol consumption

- High caffeine intake

- Irregular eating patterns

- Rapid eating

- High-fat diet

- Psychological Factors:

- Chronic stress

- Anxiety disorders

- Depression

- History of trauma or abuse

- Medical Conditions:

- Previous gastrointestinal infections

- Diabetes mellitus (gastroparesis)

- Thyroid disorders

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Gallbladder disease

Alarm Features (“ALARM” Mnemonic): Features suggesting serious underlying pathology:

- Anaemia (iron deficiency)

- Loss of weight (unintentional)

- Anorexia

- Recent onset of progressive symptoms

- Melaena/haematemesis (gastrointestinal bleeding)

Community health nurses should be particularly vigilant for these alarm symptoms, as they require prompt referral for further investigation to rule out serious conditions like malignancy.

4.3 Screening and Assessment

Effective screening and assessment for dyspepsia in community settings involves a systematic approach to identify symptom patterns, risk factors, and potential alarm features.

Initial Assessment

Community health nurses should perform a comprehensive assessment that includes:

Mnemonic: “ABCDE” of Dyspepsia Assessment

Symptom Assessment Tools

| Assessment Tool | Description | Application in Community Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Dyspepsia Symptom Questionnaire | Standardized questionnaire assessing frequency and severity of symptoms | Initial screening and monitoring of treatment response |

| Glasgow Dyspepsia Severity Score | Measures frequency of symptoms, impact on daily activities, and healthcare utilization | Quantifying severity and treatment effectiveness |

| Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire | 8-item tool assessing frequency and severity of epigastric pain, heartburn, regurgitation, and nausea | Brief assessment in community or home visits |

| Nepean Dyspepsia Index | Comprehensive assessment of symptoms and quality of life impact | Detailed evaluation of functional status and life impact |

Physical Examination

Key components of physical examination for dyspepsia include:

- Vital signs assessment

- General appearance (cachexia, pallor)

- Abdominal examination:

- Inspection for distention, visible peristalsis

- Auscultation for bowel sounds

- Palpation for tenderness, masses, organomegaly

- Percussion for fluid, gas patterns

- Cardiopulmonary examination (to rule out non-GI causes)

- Assessment for signs of anemia or weight loss

Nutritional and Lifestyle Assessment

- Dietary intake and patterns

- Meal size and timing

- Fluid intake

- Weight trends

- Alcohol and caffeine consumption

- Smoking status

- Physical activity level

- Stress levels and coping mechanisms

Community Health Nursing Role: In the community setting, nurses are ideally positioned to:

- Perform initial screening for dyspepsia symptoms

- Identify high-risk individuals who require further assessment

- Recognize alarm symptoms requiring urgent referral

- Monitor symptoms and treatment response over time

- Provide education on lifestyle modifications

- Support self-management strategies

4.4 Diagnosis

While community health nurses play a vital role in screening and initial assessment, the definitive diagnosis of dyspepsia often requires additional tests conducted by physicians or specialists.

Diagnostic Approach

The approach to diagnosis typically follows one of these strategies:

- Test and Treat for H. pylori: For younger patients without alarm features

- Empiric Acid Suppression: Trial of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

- Prompt Endoscopy: For patients with alarm features or older age (typically >55 or 60 years)

Diagnostic Tests

| Diagnostic Test | Description | Indications |

|---|---|---|

| H. pylori Testing | Urea breath test, stool antigen test, blood antibody test | Initial approach in patients <55 years without alarm features |

| Upper Endoscopy | Direct visualization of esophagus, stomach, and duodenum | Patients with alarm features, persistent symptoms, or >55 years |

| Laboratory Tests | Complete blood count, liver function, amylase/lipase, thyroid function | Rule out anemia, liver, pancreatic, or thyroid disorders |

| Abdominal Ultrasound | Non-invasive imaging of liver, gallbladder, pancreas | Suspected gallstones or pancreatic disease |

| Gastric Emptying Study | Measures rate of gastric emptying | Suspected gastroparesis |

| 24-hour pH Monitoring | Measures esophageal acid exposure | Suspected GERD when endoscopy is normal |

Diagnostic Criteria for Functional Dyspepsia (Rome IV)

Functional dyspepsia is diagnosed when the following criteria are met:

- One or more of the following symptoms:

- Postprandial fullness

- Early satiation

- Epigastric pain

- Epigastric burning

- No evidence of structural disease (including on upper endoscopy) that would explain the symptoms

- Symptoms present for the last 3 months with onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis

Community Health Nursing Role in Diagnosis:

- Facilitate diagnostic testing by ensuring patients understand procedures and preparations

- Assist with coordination of referrals to specialists

- Provide education about the diagnostic process

- Help patients navigate the healthcare system to obtain necessary tests

- Follow up on test results and communicate findings to patients

- Document findings and maintain comprehensive health records

4.5 Management and Primary Care

Management of dyspepsia in community settings focuses on symptom relief, addressing underlying causes when identified, and improving quality of life. The approach should be tailored to the type of dyspepsia (organic vs. functional) and individual patient factors.

Non-Pharmacological Management

Lifestyle Modifications

- Dietary Changes:

- Smaller, more frequent meals

- Reducing fat intake

- Avoiding trigger foods (spicy, acidic, fried)

- Limiting alcohol and caffeine

- Avoiding late-night eating

- Consideration of low FODMAP diet for selected patients

- Behavioral Modifications:

- Eating slowly and chewing thoroughly

- Maintaining upright position after meals

- Stress reduction techniques

- Regular physical activity

- Smoking cessation

- Adequate hydration

Pharmacological Management

| Medication Class | Examples | Indications and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Antacids | Aluminum hydroxide, magnesium hydroxide, calcium carbonate | Short-term symptom relief; can be used as needed for mild symptoms |

| H2 Receptor Antagonists | Ranitidine, famotidine, cimetidine | Moderate acid suppression; useful for mild to moderate symptoms |

| Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) | Omeprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole | More potent acid suppression; first-line for many patients; consider limited duration of use |

| Prokinetics | Metoclopramide, domperidone, erythromycin | For symptoms of delayed gastric emptying; monitor for side effects |

| H. pylori Eradication | Various antibiotic combinations with PPI | For H. pylori-positive dyspepsia; confirm eradication after treatment |

| Antispasmodics | Hyoscine, dicyclomine | For cramping abdominal pain; less evidence for efficacy |

| Tricyclic Antidepressants | Amitriptyline, nortriptyline (low dose) | For refractory functional dyspepsia; may help visceral hypersensitivity |

Treatment Algorithms Based on Dyspepsia Type

- H. pylori-Associated Dyspepsia:

- Eradication therapy according to local resistance patterns

- Confirm eradication with urea breath test or stool antigen test

- Reassess symptoms 4-8 weeks after treatment

- NSAID-Induced Dyspepsia:

- Discontinue or reduce NSAID if possible

- Consider alternative pain management

- If NSAID must continue, add PPI for protection

- Functional Dyspepsia – Epigastric Pain Syndrome:

- PPI trial for 4-8 weeks

- If no response, consider tricyclic antidepressant

- Address psychological factors

- Functional Dyspepsia – Postprandial Distress Syndrome:

- Dietary and lifestyle modifications

- Consider prokinetic agent

- If no response, trial of PPI

Complementary and Alternative Approaches

- Herbal Preparations:

- Peppermint oil

- Caraway oil

- Ginger

- Chamomile

- Mind-Body Therapies:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Relaxation techniques

- Hypnotherapy

- Acupuncture

Community Health Nursing Role in Management:

- Provide education about medication use and potential side effects

- Support lifestyle modifications with practical advice

- Monitor treatment effectiveness and adjust as needed

- Address psychological aspects of chronic digestive discomfort

- Ensure proper medication adherence

- Coordinate care with other healthcare providers

- Advocate for patients needing specialized care

4.6 First Aid and Home Management

While dyspepsia is rarely a medical emergency, acute episodes can cause significant digestive discomfort and distress. Community health nurses should educate patients on immediate measures to manage acute symptoms.

Immediate Relief Measures for Acute Dyspepsia

Stop Eating – If dyspepsia occurs during a meal, stop eating to prevent further distention of the stomach.

Upright Position – Sit upright or stand; avoid lying down for at least 2 hours after eating to prevent reflux.

Loosen Clothing – Loosen tight belts or clothing around the abdomen to reduce pressure on the stomach.

Over-the-Counter Remedies – Take an antacid as directed (if previously approved by healthcare provider).

Herbal Teas – Consider peppermint, ginger, or chamomile tea for mild symptoms.

Relaxation Techniques – Practice deep breathing or relaxation techniques to reduce stress-related symptoms.

Home Remedies with Evidence Base

- Ginger: May help with nausea and gastric motility; can be consumed as tea or capsules

- Peppermint: May relax gastrointestinal muscles; avoid in GERD as it can worsen reflux

- Apple Cider Vinegar: Some anecdotal evidence for relief; use diluted (1-2 tsp in water)

- Baking Soda: Acts as a natural antacid (1/2 tsp in water); use sparingly due to sodium content

- Chamomile Tea: Has anti-inflammatory and calming properties

- Licorice (DGL): May help protect the stomach lining; use deglycyrrhizinated form to avoid side effects

Self-Monitoring Techniques

Teach patients to monitor their dyspepsia through:

- Food and symptom diaries to identify triggers

- Pain scales to track symptom severity

- Timing patterns related to meals and activities

- Response to interventions and medications

When to Seek Immediate Medical Attention:

- Severe, sudden-onset pain that radiates to jaw, neck, or arm

- Shortness of breath or chest pain accompanying digestive discomfort

- Vomiting blood or material that looks like coffee grounds

- Black, tarry stools

- Severe, persistent abdominal pain

- Signs of dehydration from persistent vomiting

4.7 Referral Criteria

Community health nurses should be aware of when to refer patients with dyspepsia for further evaluation and specialized care.

Urgent Referral Indications

- Presence of any alarm symptoms from the “ALARM” mnemonic

- Age >55 years with new-onset dyspepsia

- Symptoms suggestive of cardiac origin

- Persistent vomiting

- Signs of gastrointestinal bleeding

- Significant unintentional weight loss

- Severe pain unresponsive to initial management

- Progressive dysphagia

Specialist Referrals

| Specialist | Indications for Referral | Services Provided |

|---|---|---|

| Gastroenterologist | Persistent symptoms despite primary care management, alarm features, need for endoscopy | Endoscopy, specialized testing, advanced treatment options |

| Dietitian | Need for specialized diet planning, significant weight loss, complex dietary needs | Personalized dietary assessment and planning |

| Mental Health Professional | Significant psychological overlay, anxiety, depression affecting symptoms | Psychological therapies, stress management |

| Pain Specialist | Chronic, refractory pain not responding to standard treatments | Advanced pain management techniques |

| Surgeon | Suspected surgical conditions (e.g., gallstones, severe GERD with indication for fundoplication) | Surgical interventions for structural causes |

Information to Include in Referrals

- Detailed symptom history including onset, duration, and progression

- Previous treatments attempted and responses

- Current medications and allergies

- Relevant medical history

- Results of any previous investigations

- Presence of alarm features

- Impact on quality of life and daily functioning

- Patient’s preferences and concerns

The Role of Community Health Nurses in the Referral Process:

- Identify patients requiring specialist referral based on established criteria

- Facilitate timely referrals for those with alarm features

- Prepare patients for specialist consultations with appropriate information

- Follow up on referral outcomes and incorporate recommendations into care plans

- Coordinate care between primary care providers and specialists

- Advocate for patients facing barriers to accessing specialty care

5. Community Health Nursing Approach

Community health nurses are uniquely positioned to manage dysphagia and dyspepsia through a comprehensive approach that extends beyond individual care to include family and community interventions.

Comprehensive Care Model

| Care Level | Dysphagia Interventions | Dyspepsia Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Individual |

|

|

| Family |

|

|

| Community |

|

|

Implementation of Standing Orders in Community Practice

Effective implementation of standing orders for dysphagia and dyspepsia requires:

- Development of clear protocols with physician collaboration

- Regular training and competency assessment for community nurses

- Established documentation and communication pathways

- Regular review and updates based on current evidence

- Quality assurance measures to evaluate outcomes

Example Standing Order Template for Dysphagia Screening:

- Purpose: To identify individuals at risk for dysphagia and implement immediate safety measures

- Population: Adults with identified risk factors (stroke, neurological conditions, frailty, age >70)

- Assessment: Authorized use of validated screening tool (e.g., water swallow test)

- Intervention: Implementation of immediate dietary modifications based on results

- Referral: Clear criteria for when specialist referral is required

- Documentation: Required elements for electronic health record

- Follow-up: Timeline for reassessment based on risk level

Health Promotion and Prevention

Community health nurses should incorporate preventive strategies for dysphagia and dyspepsia:

- Primary Prevention:

- Education on healthy eating habits

- Promotion of regular physical activity

- Stress management techniques

- Smoking cessation programs

- Safe medication use education

- Secondary Prevention:

- Regular screening of high-risk populations

- Early identification and management of symptoms

- Monitoring for medication side effects

- Early intervention for emerging swallowing difficulties

- Tertiary Prevention:

- Prevention of complications in those with established conditions

- Optimization of management to prevent deterioration

- Support for adaptation to chronic conditions

- Rehabilitation approaches to maximize function

Patient Education and Self-Management

Education is a cornerstone of effective community management for both conditions:

Key Educational Components

- Clear explanation of the condition in understandable terms

- Practical strategies for symptom management

- Proper use of prescribed medications

- Recognition of warning signs requiring medical attention

- Dietary and lifestyle modifications specific to the condition

- Self-monitoring techniques and tools

- Stress management and psychological coping strategies

- Resources for additional support and information

Care Coordination and Advocacy

Community health nurses serve as coordinators and advocates by:

- Facilitating communication between healthcare providers

- Ensuring continuity of care across settings

- Navigating complex healthcare systems on behalf of patients

- Addressing socioeconomic barriers to care

- Advocating for needed services and resources

- Coordinating multidisciplinary care approaches

- Supporting transitions between care settings

6. Global Best Practices

Community health nursing approaches to dysphagia and dyspepsia management vary globally, with several innovative practices that can be adapted to different settings.

Dysphagia Management Innovations

Japan: Integrated Community Care Model

Japan has developed an integrated community-based approach to dysphagia management in its aging population:

- Community-based swallowing assessments incorporated into regular health check-ups

- Standardized training for family caregivers in safe feeding techniques

- Specialized “swallowing rehabilitation teams” that provide home visits

- Use of telemedicine for remote assessment and monitoring of swallowing function

- Community awareness campaigns about swallowing difficulties and their management

Sweden: Multidisciplinary Approach

Sweden employs a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach to dysphagia management:

- Integrated teams including nurses, speech therapists, dietitians, and physicians

- Standardized national guidelines for dysphagia screening and management

- Regular competency training for all healthcare providers

- Innovative food texture modifications and presentation techniques

- Technology-assisted swallowing therapy with biofeedback

Dyspepsia Management Innovations

Australia: Stepped Care Model

Australia has implemented a stepped care approach to dyspepsia management:

- Risk stratification protocols used in primary care

- Nurse-led clinics for initial assessment and management of uncomplicated dyspepsia

- Standardized pathways for escalation to specialist care

- Integration of psychological support services

- Digital health platforms for patient self-management and monitoring

United Kingdom: Community Gastroenterology Services

The UK has developed community-based gastroenterology services:

- Specialized gastrointestinal nurse practitioners in community settings

- Direct access to diagnostic testing from primary care

- Community-based endoscopy services

- Integrated care pathways for common digestive complaints

- Strong emphasis on self-management support

Transferable Best Practices

Key elements that can be adapted across different settings include:

- Implementation of standardized screening protocols

- Development of clear referral pathways

- Integration of multidisciplinary approaches

- Emphasis on family and caregiver education

- Utilization of telehealth for remote assessment and follow-up

- Community-based rehabilitation approaches

- Expanded roles for community health nurses in specialized assessment and management

- Development of culturally appropriate resources and interventions

Implementation Considerations: When adapting global practices to local contexts, community health nurses should consider:

- Available resources and infrastructure

- Local healthcare system structure and funding

- Cultural attitudes toward health and illness

- Training and competency needs of healthcare staff

- Regulatory and scope of practice considerations

- Community needs assessment findings

7. Conclusion

Dysphagia and dyspepsia represent common but often challenging conditions encountered in community health nursing practice. This comprehensive guide has outlined evidence-based approaches to screening, diagnosis, management, and referral of these conditions, with a focus on practical implementation in community settings.

Key Points to Remember

- Early identification through systematic screening is essential for preventing complications

- Standing orders can enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of care delivery

- A multidisciplinary approach optimizes outcomes for both conditions

- Patient and caregiver education is central to successful management

- First aid protocols for emergencies related to these conditions should be widely taught

- Clear referral pathways ensure timely access to specialized care when needed

- Community health nurses play a vital role in coordinating care across the healthcare continuum

The Role of the Community Health Nurse

As a community health nurse, your comprehensive approach to swallowing disorders and digestive discomfort makes a significant difference in patients’ lives. By implementing the strategies outlined in this guide, you can:

- Improve early detection and management of dysphagia and dyspepsia

- Prevent serious complications through timely intervention

- Enhance patients’ quality of life and functional independence

- Support caregivers in providing safe and effective care

- Optimize healthcare resource utilization through appropriate management

- Contribute to improved community health outcomes

By integrating the knowledge, tools, and strategies presented in this guide into your practice, you are equipped to provide high-quality, evidence-based care for individuals with dysphagia and dyspepsia in community settings.

8. References

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2023). Adult Dysphagia. https://www.asha.org/practice-portal/clinical-topics/adult-dysphagia/

- American Academy of Family Physicians. (2019). What standing orders can do for your practice. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/fpm/blogs/inpractice/entry/potential_standing_orders.html

- American Heart Association. (2022). Dysphagia Screen. https://www.heart.org/-/media/data-import/downloadables/5/5/7/dysphagia-ucm_497694.pdf

- American Family Physician. (2020). Functional Dyspepsia: Evaluation and Management. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2020/0115/p84.html

- Cleveland Clinic. (2024). Dysphagia (Difficulty Swallowing). https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/21195-dysphagia-difficulty-swallowing

- Cleveland Clinic. (2024). Functional Dyspepsia. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22248-functional-dyspepsia

- DysphagiaStudy.com. (2022). Dysphagia Management: BOLUS Framework. https://swallowstudy.com/dysphagia-management-bolus-framework/

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (2023). Dysphagia: What Happens During a Bedside Swallow Exam. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/dysphagia-what-happens-during-a-bedside-swallow-exam

- Mayo Clinic. (2024). Dysphagia – Diagnosis and treatment. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/dysphagia/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20372033

- Mayo Clinic. (2025). Functional dyspepsia – Diagnosis and treatment. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/functional-dyspepsia/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20375715

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (2024). Treatment of Indigestion. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/indigestion-dyspepsia/treatment

- Nursing Times. (2017). Detecting dysphagia. https://www.myamericannurse.com/detecting-dysphagia/

- PubMed Central. (2023). A Comprehensive Assessment Protocol for Swallowing (CAPS). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9963613/

- PubMed Central. (2024). Perspective on dysphagia screening, assessment methods, and intervention. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11035756/

- Stroke Journal. (2023). Dysphagia Screening: State of the Art. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/str.0b013e3182877f57

- University of California San Francisco. (2023). Standing Orders. https://cepc.ucsf.edu/standing-orders