Maternal Positions During First Stage of Labor

Evidence-Based Guide for Nursing Practice

Nursing Notes

Last Updated: May 2025

Table of Contents

Introduction

Maternal positioning during labor is a critical yet often underutilized nursing intervention that can significantly impact labor progression, maternal comfort, and birth outcomes. This evidence-based guide focuses on optimal positioning strategies during the first stage of labor, providing nursing students with the knowledge needed to support laboring women effectively.

Clinical Pearl

Maternal positioning is a non-pharmacological, cost-effective intervention that empowers both the laboring woman and care provider. Nurses who understand the biomechanical principles behind positioning can significantly contribute to a more positive birth experience.

First Stage of Labor: An Overview

The first stage of labor begins with regular uterine contractions leading to progressive cervical dilation and ends when the cervix is fully dilated at 10 cm. This stage is typically divided into:

| Phase | Cervical Dilation | Typical Duration (Nulliparous) | Typical Duration (Multiparous) | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent Phase | 0-6 cm | Up to 20 hours | Up to 14 hours | Mild to moderate contractions, gradual cervical effacement and dilation |

| Active Phase | 6-8 cm | Average 5 hours | Average 2-3 hours | Regular, stronger contractions with more rapid cervical change |

| Transition Phase | 8-10 cm | 30 mins – 2 hours | 15-60 mins | Intense contractions, rapid dilation, maternal distress often peaks |

During the first stage of labor, positioning strategies should be adapted to each phase, with consideration for maternal comfort, labor progress, and fetal position. Evidence shows that restrictive positioning policies can negatively impact labor progression and maternal satisfaction.

Physiological Basis of Positioning

Understanding the biomechanics of the pelvis during labor provides the foundation for evidence-based positioning. Key physiological principles include:

Gravitational Advantage

Upright positions utilize gravity to assist with fetal descent through the birth canal. When a woman is upright, the gravitational force (9.8 m/s²) aids the downward pressure of the presenting part against the cervix, potentially increasing the efficiency of contractions.

Pelvic Dimension Changes

Different positions alter pelvic dimensions. For example, squatting increases the pelvic outlet diameter by up to 28% compared to supine positioning by tilting the sacrum and creating more space for the fetus to navigate through the birth canal.

Uterine Blood Flow

Supine positions can lead to aortocaval compression, reducing blood flow to the uterus by up to 30-40%. Lateral and upright positions optimize uteroplacental perfusion, improving fetal oxygenation and potentially reducing fetal distress.

Contraction Efficiency

Upright and forward-leaning positions have been shown to increase contraction intensity and frequency by 10-15% compared to recumbent positions. This improves coordination of uterine muscle fibers and optimizes the mechanics of labor.

Evidence Highlight

A meta-analysis published by the Cochrane Collaboration found that women who used upright positions and ambulation during the first stage of labor experienced an average reduction in labor duration of approximately 1 hour and 22 minutes compared to those who remained in recumbent positions.

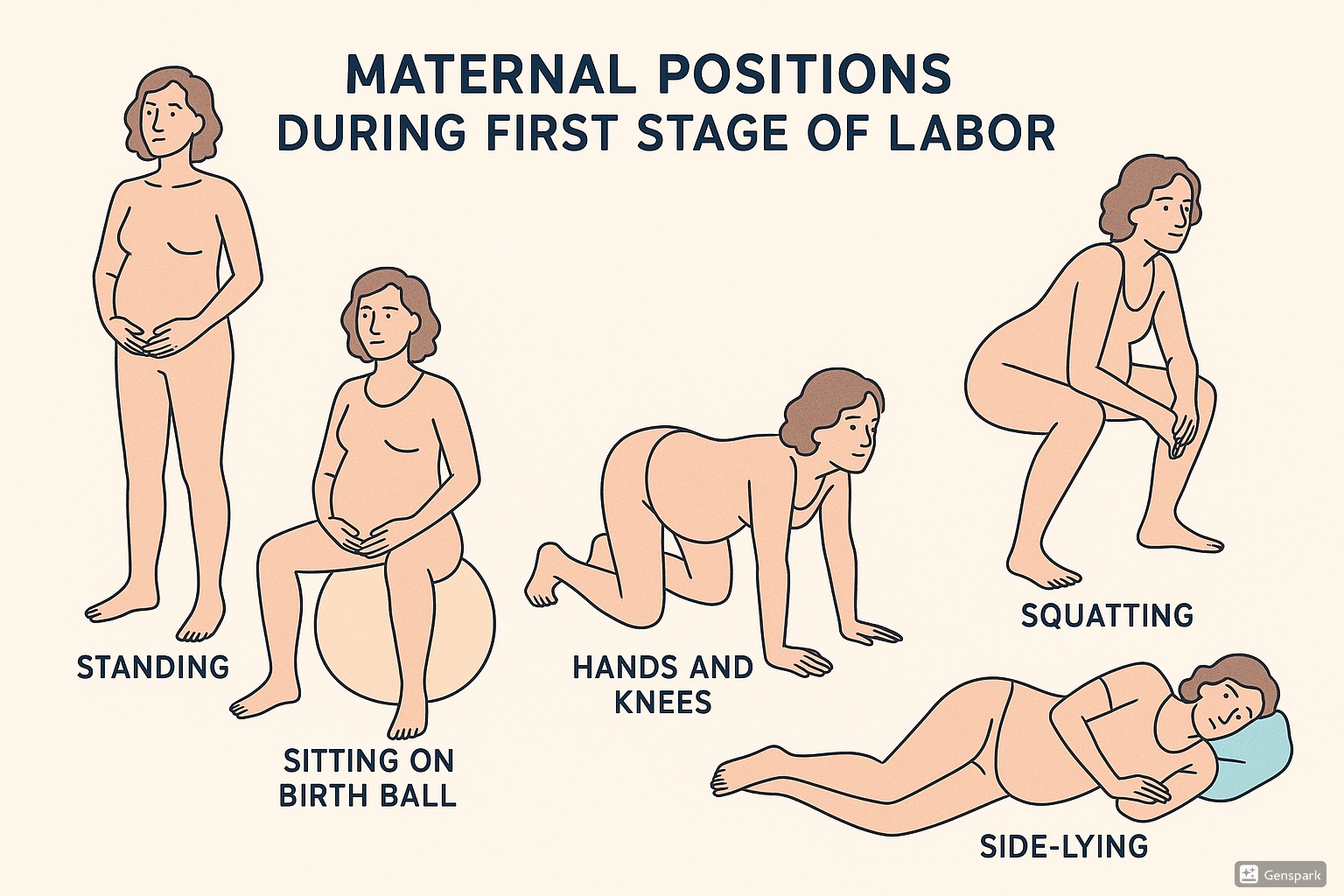

Evidence-Based Positioning Options

Research supports a variety of positioning options during the first stage of labor. The following positions have demonstrated benefits for labor progression and maternal comfort:

Upright Positions & Ambulation

| Position | Description | Benefits | Nursing Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standing/Walking | Upright position with support from partner or wall as needed; gentle ambulation between contractions |

|

|

| Sitting on Birth Ball | Seated on appropriately sized stability ball with feet flat on floor |

|

|

| Squatting | Deep squat with support from partner, squat bar, or birthing stool |

|

|

| Leaning Forward | Standing or kneeling while leaning forward onto bed, partner, wall, or birth ball |

|

|

Memory Aid: “STEP Up”

Remember the key upright positions with the acronym “STEP Up”:

- Standing/Walking – Utilizes gravity and increases maternal autonomy

- Tall Kneeling – Excellent for back labor and posterior presentations

- Elevated Squatting – Maximizes pelvic outlet diameter

- Pelvet (Birth Ball) Sitting – Promotes mobility while conserving energy

- Upright positions generally – Reduce labor duration and intervention rates

Lateral & Recumbent Positions

| Position | Description | Benefits | Nursing Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Side-Lying | Lateral recumbent position, typically with upper leg supported by pillows or peanut ball |

|

|

| Semi-Recumbent | Partially reclined position with upper body elevated 30-45 degrees |

|

|

| Hands and Knees | All-fours position with weight supported on hands and knees |

|

|

| Asymmetrical Positions | Positions that create asymmetry in the pelvis, such as lunge, stair climbing, or curb walking |

|

|

Memory Aid: “SLASH”

Key non-upright positions can be remembered with the acronym “SLASH”:

- Side-Lying – Optimal for rest while maintaining pelvic space

- Lunge – Creates asymmetry to help with fetal rotation

- All Fours – Perfect for posterior babies and back pain relief

- Semi-Recumbent – Better than supine for monitoring and interventions

- Hands and Knees – Facilitates optimal fetal positioning and rotation

Nursing Considerations

Effective implementation of positioning strategies requires careful nursing assessment and individualized approaches. Consider the following factors when supporting maternal positioning during labor:

Assessment Factors

- Maternal preferences and cultural considerations

- Stage and phase of labor

- Fetal position and presentation

- Pain level and location

- Presence of regional anesthesia

- Maternal mobility and energy levels

- Medical conditions or complications

- Previous birth experiences

Implementation Strategies

- Provide evidence-based education about positioning options

- Suggest position changes every 30-45 minutes

- Adapt positioning to changing labor conditions

- Ensure adequate support and safety with each position

- Document positions used and their effects

- Advocate for mobility when medically appropriate

- Create an environment that supports position changes

- Involve support persons in positioning assistance

Clinical Pearl: Position Rotation Protocol

Develop a systematic approach to position rotation during labor. Research indicates that changing positions approximately every 30 minutes can optimize the mechanics of labor while preventing maternal fatigue and discomfort in any single position. Create a “position menu” with pictures to help women and their support persons visualize options and make informed choices.

Important Considerations

While encouraging position changes and mobility, always:

- Respect maternal autonomy and preferences

- Modify approaches based on individual circumstances

- Consider safety with all position recommendations

- Document contraindications to specific positions

- Adapt positioning when continuous monitoring is required

- Be aware that the supine position should be avoided when possible due to potential aortocaval compression

Best Practices & Recent Updates

The field of maternal positioning during labor continues to evolve with new research and clinical guidelines. Here are three key recent updates and best practices:

1. Peanut Ball Protocol for Epidural Recipients

Recent research has demonstrated that the use of a peanut ball (an elongated exercise ball) between the legs of women with epidural anesthesia can significantly reduce labor duration and increase rates of spontaneous vaginal delivery. A 2024 systematic review found that peanut ball use reduced first stage labor duration by an average of 90 minutes and second stage by 22 minutes compared to standard care without a peanut ball.

Practice Update: Incorporate peanut ball positioning into standard care for women with limited mobility due to epidural anesthesia, alternating sides every 30-45 minutes.

2. Biomechanics-Based Positioning for Malpositions

Advanced understanding of pelvic biomechanics has led to more targeted positioning strategies for specific fetal positions. For posterior presentations (occiput posterior), forward-leaning positions that create more space in the posterior pelvis have been shown to facilitate rotation. The “spinning babies” approach that incorporates specific sequences of positions based on fetal presentation is gaining clinical recognition.

Practice Update: Utilize targeted positions based on fetal presentation rather than generic positioning protocols. For example, hands-and-knees, lunges, and asymmetrical positions for posterior presentations; side-lying with peanut ball for transverse arrest.

3. Nurse Education on Positioning Options

Research indicates that nurses who receive specific education on maternal positioning techniques demonstrate greater confidence in supporting diverse positions and are more likely to encourage maternal mobility during labor. A 2023 quality improvement study found that after a comprehensive positioning education program, nurses were 38% more likely to suggest alternative positions during labor and reported increased confidence in supporting women in non-traditional positions.

Practice Update: Healthcare facilities are increasingly implementing mandatory education on positioning options for labor and delivery nurses, including hands-on practice with positioning tools like birthing balls, peanut balls, and squat bars.

Memory Aids for Nursing Students

The “POSITION” Framework

Use this acronym to remember key considerations when supporting maternal positioning:

- Preferences – Always consider maternal comfort and preferences

- Optimize – Choose positions that optimize pelvic dimensions for specific presentations

- Safety – Ensure positions are implemented safely with adequate support

- Intermittent – Change positions approximately every 30-45 minutes

- Track – Document positions used and their effects on labor progress

- Individualize – Adapt positioning based on unique circumstances

- Observe – Monitor maternal and fetal response to position changes

- Nurture – Support and encourage maternal confidence with positioning choices

The “4 P’s of Positioning”

This framework helps match positions to specific labor challenges:

- Pain Relief: Hands and knees, leaning forward, water immersion

- Progress Enhancement: Upright positions, squatting, lunges, asymmetrical positions

- Pelvic Opening: Squatting (outlet), hands and knees (posterior space), side-lying with peanut ball (transverse)

- Pressure Relief: Side-lying (aortocaval), hands and knees (back pain), standing/leaning (perineal)

Positioning Timeline Mnemonic: “LAPS”

Remember optimal position progression throughout first stage labor:

- Latent phase: Ambulation, upright positions, normal activities

- Active phase: Alternating between upright and restful positions

- Progression slowing: Position changes targeting specific challenges

- Second stage approaching: Positions that optimize pelvic outlet dimensions

Conclusion

Supporting women with evidence-based positioning during the first stage of labor represents a core nursing competency that can significantly impact birth outcomes. By understanding the physiological basis of positioning, recognizing individual needs, and implementing appropriate positioning strategies, nurses can enhance the labor experience while potentially reducing the need for interventions.

Remember that the most effective approach combines scientific knowledge with respect for maternal autonomy and preferences. Regular position changes, individualized to the specific circumstances of each laboring woman, provide the foundation for optimal labor support.

References

1. Lawrence, A., Lewis, L., Hofmeyr, G. J., & Styles, C. (2013). Maternal positions and mobility during first stage labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (10), CD003934. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24105444/

2. Kibuka, M., & Thornton, J. G. (2017). Position in the second stage of labour for women with epidural anaesthesia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), CD008070.

3. Berghella, V., et al. (2023). Normal Labor: Physiology, Evaluation, and Management. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544290/

4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2019). Approaches to Limit Intervention During Labor and Birth. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 766. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 133, e164-e173. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2019/02/approaches-to-limit-intervention-during-labor-and-birth

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2024). First and Second Stage Labor Management. Clinical Practice Guideline. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/clinical-practice-guideline/articles/2024/01/first-and-second-stage-labor-management

6. McCallum, S., et al. (2023). Educating Nursing Staff on Evidence-Based Maternal Positioning to Improve Birth Outcomes. University of San Francisco Repository. https://repository.usfca.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2865&context=capstone

7. Bueno-Lopez, V., et al. (2021). Effect of the birthing position on its evolution from a biomechanical point of view. Journal of Biomechanics, 114, 110148. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33422852/

8. Wickham, S. (2022). Upright positions in labour – the benefits. https://www.sarawickham.com/original-articles/upright-positions/

9. McCollum, B. S. (2021). Pelvic biomechanics and movement in labor. Evidence Based Birth Podcast #196. https://evidencebasedbirth.com/pelvic-biomechanics-and-movement-in-labor-with-brittany-sharpe-mccollum/

10. Mayo Clinic. (2023). Labor positions. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/labor-and-delivery/in-depth/labor/art-20546804