Comprehensive Guide to Obstetric Anesthesia and Analgesia

A detailed resource for nursing students

Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction to Obstetric Anesthesia

- 2. Physiological Changes in Pregnancy Affecting Anesthesia

- 3. Pain Pathways in Labor and Delivery

- 4. Neuraxial Anesthesia Techniques

- 5. Systemic Analgesia

- 6. Inhalational Analgesia

- 7. Regional Nerve Blocks

- 8. General Anesthesia in Obstetrics

- 9. Anesthetic Considerations for Different Delivery Scenarios

- 10. Complications and Management

- 11. Nursing Considerations and Responsibilities

- 12. Pharmacology of Anesthetic Agents in Obstetrics

- 13. Special Circumstances in Obstetric Anesthesia

- 14. Global Best Practices in Obstetric Anesthesia

- 15. References and Further Reading

1. Introduction to Obstetric Anesthesia

Obstetric anesthesia represents a specialized branch of anesthesiology focused on providing pain relief during labor and delivery while ensuring the safety of both mother and fetus. The primary goals of obstetric anesthesia are to alleviate maternal pain, facilitate obstetric interventions when necessary, and maintain maternal and fetal physiologic homeostasis. This specialized field requires a deep understanding of the physiological changes that occur during pregnancy and their impact on anesthetic management.

Key Concepts in Obstetric Anesthesia

Obstetric anesthesia encompasses a range of techniques and approaches tailored to the unique needs of pregnant women. Pain management during childbirth has evolved significantly over centuries, from simple herbal remedies to sophisticated neuraxial techniques. Today’s obstetric anesthesia practice balances maternal comfort with safety considerations for both mother and baby. The field continues to evolve with ongoing research and technological advancements aimed at improving maternal outcomes and experiences.

As a nursing student, understanding the principles and applications of obstetric anesthesia is crucial for providing comprehensive care to pregnant patients. Nurses play a vital role in the assessment, monitoring, and care of women receiving anesthetic interventions during the peripartum period. This comprehensive guide aims to provide you with the knowledge and skills necessary to assist in the safe and effective administration of anesthesia and analgesia in obstetric settings.

Historical Perspective

The first documented use of anesthesia in childbirth occurred in 1847 when Sir James Young Simpson administered ether to a woman during delivery. Later that year, Queen Victoria’s use of chloroform during the birth of Prince Leopold in 1853 (known as “anesthesia à la reine”) helped overcome religious and social objections to pain relief during childbirth. The evolution of obstetric anesthesia has since been marked by significant advances in pharmacology, equipment, and techniques, all aimed at improving safety and efficacy.

2. Physiological Changes in Pregnancy Affecting Anesthesia

Pregnancy induces profound physiological changes that significantly impact anesthetic management. Understanding these adaptations is essential for safe obstetric anesthesia practice. These changes affect nearly every organ system and alter the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of anesthetic drugs.

Critical Physiological Adaptations

During pregnancy, maternal physiological changes create unique challenges for obstetric anesthesia planning and administration. These adaptations begin early in pregnancy and generally reach their maximum effect by the third trimester.

| Physiological System | Changes During Pregnancy | Anesthetic Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular |

|

|

| Respiratory |

|

|

| Gastrointestinal |

|

|

| Nervous System |

|

|

| Hematological |

|

|

| Renal |

|

|

Mnemonic: ADAPT for Pregnancy Physiological Changes

A – Airway changes (edema, difficult intubation)

D – Displacement (aortocaval compression, left uterine displacement needed)

A – Aspiration risk (increased gastric pressure, delayed emptying)

P – Perfusion changes (increased blood volume, cardiac output)

T – Thrombotic risk (hypercoagulability of pregnancy)

These physiological adaptations make pregnant women particularly vulnerable to certain complications during anesthesia. For example, the decreased functional residual capacity combined with increased oxygen consumption results in a dramatically shortened period before desaturation occurs during apnea. Additionally, the aortocaval compression can lead to profound hypotension when the parturient is placed in a supine position, especially after neuraxial anesthesia administration. Understanding these changes and their implications is foundational for safe obstetric anesthesia practice.

3. Pain Pathways in Labor and Delivery

Labor pain is complex and involves multiple neural pathways. Understanding the origin and transmission of labor pain is essential for selecting appropriate obstetric anesthesia techniques. Pain during childbirth occurs in stages and involves different anatomical structures as labor progresses.

Labor Pain Origins

Labor pain occurs in two distinct phases with different neuroanatomical pathways:

- First Stage (Cervical Dilation): Pain arises from uterine contractions, cervical dilation, and lower uterine segment stretching. This visceral pain is transmitted via sympathetic afferent fibers through the hypogastric and aortic plexuses, entering the spinal cord at T10-L1 levels.

- Second Stage (Descent): Pain originates from vaginal and perineal stretching. This somatic pain is transmitted through the pudendal nerve and enters the spinal cord at S2-S4 levels.

Neural Transmission of Labor Pain

The comprehensive understanding of pain pathways in obstetric anesthesia is crucial for providing effective pain management. Pain signals from the uterus, cervix, and birth canal are transmitted through complex neural networks:

| Labor Stage | Pain Source | Neural Pathway | Spinal Level | Appropriate Analgesia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent Phase | Uterine contractions, cervical dilation | Sympathetic fibers via hypogastric plexus | T10-T12 | Epidural (low concentration), systemic opioids |

| Active Phase | Intensified uterine contractions, cervical dilation | Sympathetic fibers via hypogastric plexus | T10-L1 | Epidural, combined spinal-epidural |

| Transition Phase | Maximum cervical dilation, early descent | Sympathetic and beginning somatic pathways | T10-L1, S2-S4 | Epidural, combined spinal-epidural |

| Second Stage | Descent, vaginal and perineal stretching | Pudendal nerve, other somatic pathways | S2-S4 | Epidural, pudendal block |

| Third Stage | Placental delivery, uterine contractions | Sympathetic pathways | T10-L1 | Continuation of existing analgesia |

This distinct dual innervation of labor pain explains why different obstetric anesthesia techniques are more effective at different stages of labor. For example, a T10-L1 epidural block effectively manages first-stage labor pain but may be insufficient for perineal pain during the second stage, which requires coverage of sacral segments.

Clinical Pearl

When a laboring patient reports adequate pain relief from contractions but continued perineal pain during pushing, this often indicates insufficient sacral coverage in the neuraxial block. Consider a “top-up” dose of local anesthetic or extension of the block to cover S2-S4 dermatomes.

Pain Perception and Modulation

Beyond anatomical pathways, labor pain perception is influenced by multiple psychosocial and physiological factors:

- Endogenous Pain Modulation: The body’s natural pain control involves endorphins and descending inhibitory pathways that may be enhanced through techniques like controlled breathing.

- Psychosocial Factors: Previous experiences, cultural background, preparation for childbirth, and support during labor significantly influence pain perception.

- Gate Control Theory: This theory explains how non-painful stimuli can interfere with pain transmission, forming the basis for non-pharmacological pain management techniques.

- Fear-Tension-Pain Cycle: Anxiety increases muscle tension and pain perception, which in turn increases anxiety, creating a cycle that effective obstetric anesthesia aims to break.

Definition: Obstetric anesthesia encompasses the specialized techniques and approaches used to manage pain during labor and delivery, targeting specific neural pathways involved in the transmission of labor-related pain while considering the physiological, psychological, and safe maternal-fetal outcomes.

Understanding these pain pathways and modulating factors helps in selecting the most appropriate analgesic interventions at different stages of labor, balancing efficacy with safety for both mother and baby.

4. Neuraxial Anesthesia Techniques

Neuraxial techniques represent the gold standard for pain management in obstetric anesthesia, offering superior analgesia while allowing the mother to remain conscious and participate in the birth experience. These techniques include epidural, spinal, and combined spinal-epidural (CSE) approaches, each with specific indications, techniques, and considerations.

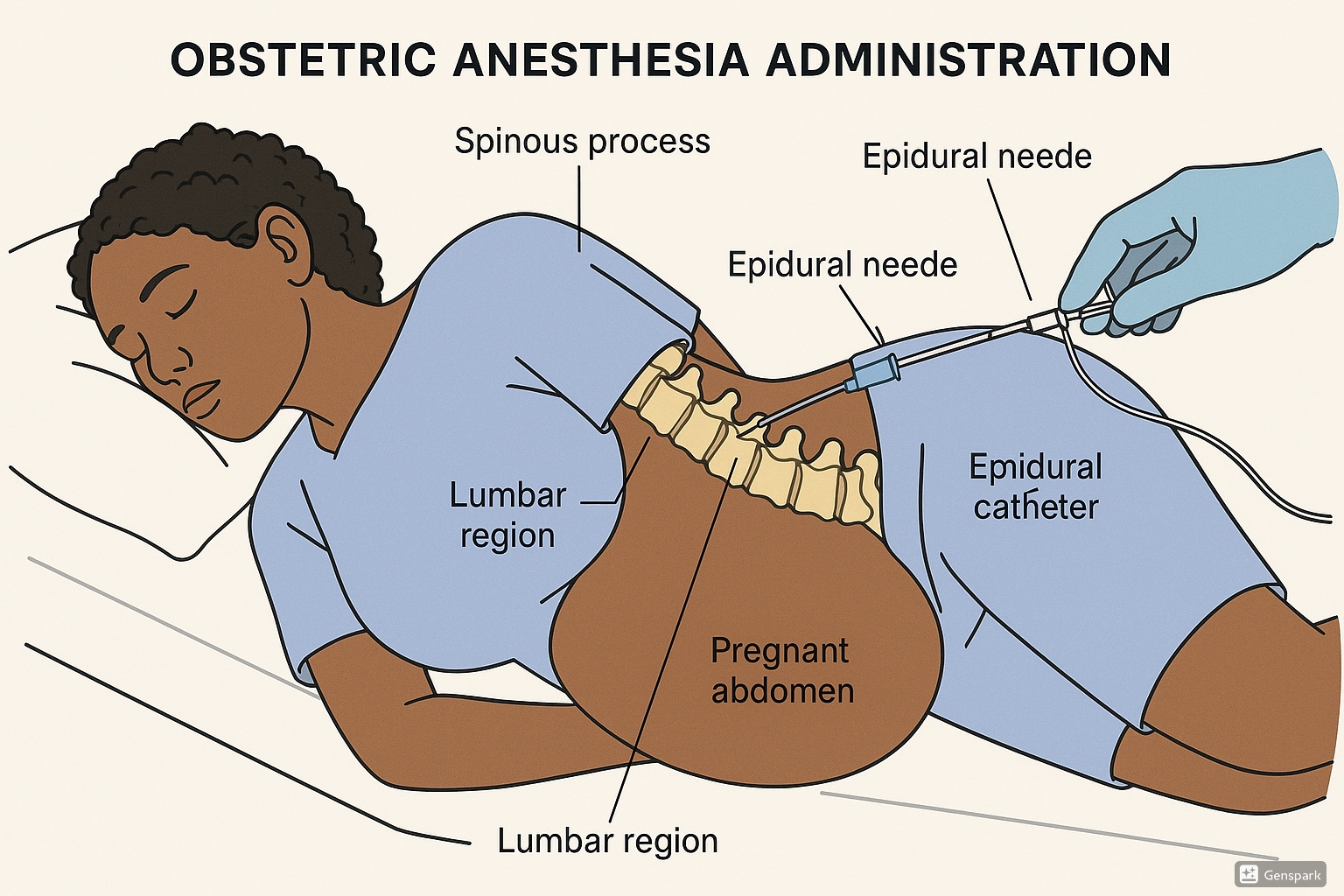

4.1 Epidural Anesthesia

Epidural anesthesia has become the cornerstone of obstetric pain management, offering continuous, titrated pain relief throughout labor and delivery. This technique involves delivering local anesthetic and sometimes opioid medications into the epidural space, the potential space between the ligamentum flavum and the dura mater.

Technique Overview

- Patient positioning (lateral decubitus or sitting position)

- Strict aseptic technique and skin preparation

- Local anesthetic infiltration at insertion site (typically L3-L4 or L2-L3)

- Identification of epidural space using loss of resistance technique

- Catheter insertion 3-5 cm into the epidural space

- Test dose administration to rule out intravascular or intrathecal placement

- Loading dose followed by continuous infusion or patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA)

Advantages of Epidural Anesthesia in Obstetric Anesthesia

- Continuous pain relief throughout labor with ability to titrate

- Preservation of maternal pushing efforts with modern low-concentration techniques

- Can be extended for cesarean delivery if required

- Decreased maternal catecholamine levels, potentially improving uteroplacental perfusion

- Reduced need for systemic medications that could affect the fetus

- Maternal alertness and participation in the birth experience

Common Epidural Medication Regimens

Modern obstetric epidural analgesia typically uses a combination of low-concentration local anesthetic (bupivacaine 0.0625-0.125% or ropivacaine 0.1-0.2%) with a lipophilic opioid (fentanyl 1-2 mcg/mL or sufentanil 0.1-0.3 mcg/mL). This combination provides superior analgesia while minimizing motor blockade and other side effects.

Potential Complications

| Complication | Incidence | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Hypotension | 10-30% | Left uterine displacement, intravenous fluids, vasopressors |

| Dural puncture | 1-2% | Convert to spinal or place epidural at another level |

| Post-dural puncture headache | 60-80% after dural puncture | Conservative management, epidural blood patch if severe |

| Inadequate analgesia | 10-15% | Catheter manipulation, replacement, supplemental analgesia |

| Intravascular injection | ~1% | Test dose to detect, treatment of local anesthetic toxicity if occurs |

| Neurological injury | < 0.01% | Immediate neurological consultation, imaging |

| Infection | 0.05% | Antibiotics, catheter removal, surgical consultation if abscess |

Nursing Considerations for Epidural Care

- Monitor maternal vital signs every 5 minutes for 20 minutes after administration, then every 30 minutes

- Monitor fetal heart rate continuously during and after epidural placement

- Assess pain levels and sensory blockade regularly

- Evaluate motor function using a Bromage scale

- Assist with position changes every 1-2 hours to prevent pressure injuries

- Maintain catheter site integrity and observe for signs of infection

- Monitor urinary output and assist with bladder emptying if needed

4.2 Spinal Anesthesia

Spinal anesthesia, also known as subarachnoid block, involves the injection of local anesthetic directly into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the subarachnoid space. This technique provides rapid, dense anesthesia and is particularly useful for cesarean deliveries and short procedures.

Key Features of Spinal Anesthesia

- Single injection technique (typically at L3-L4 or L4-L5)

- Rapid onset of action (3-5 minutes)

- Dense, reliable block suitable for surgical procedures

- Limited duration (typically 1.5-3 hours depending on medication)

- Lower medication doses compared to epidural techniques

- Higher incidence of hypotension compared to epidural

Mnemonic: SIMPLE for Spinal Assessment

S – Sensory level (assess dermatome level)

I – Injection site care

M – Motor function (Bromage score)

P – Pressure (blood pressure monitoring)

L – Level of consciousness

E – Eliminate (urinary function)

Common Medications for Obstetric Spinal Anesthesia

| Medication | Typical Dose | Onset | Duration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bupivacaine (hyperbaric) | 10-12.5 mg | 5-8 min | 1.5-3 hours | Most commonly used for cesarean delivery |

| Lidocaine | 60-75 mg | 3-5 min | 60-90 min | Shorter duration, higher risk of TNS |

| Ropivacaine | 15-18 mg | 5-10 min | 2-3 hours | Less cardiotoxic than bupivacaine |

| Fentanyl (adjuvant) | 10-25 mcg | 5-10 min | 2-4 hours | Added to improve analgesia quality, reduce local anesthetic dose |

| Morphine (adjuvant) | 100-200 mcg | 30-60 min | 12-24 hours | Provides extended postoperative analgesia, monitor for respiratory depression |

Clinical Pearl

For emergency cesarean delivery, spinal anesthesia can be faster to establish than extending a laboring epidural, provided the patient is not in severe distress and doesn’t have contraindications. The addition of intrathecal preservative-free morphine (100-200 mcg) provides excellent postoperative pain relief for up to 24 hours after cesarean delivery.

4.3 Combined Spinal-Epidural (CSE)

Combined spinal-epidural (CSE) technique merges the advantages of both spinal and epidural anesthesia, providing rapid onset of profound analgesia (spinal component) with the ability to extend the duration and titrate the level of block through the epidural catheter (epidural component).

Combined Spinal-Epidural Technique

- Epidural space is identified using standard loss of resistance technique

- A long spinal needle is passed through the epidural needle to pierce the dura

- Small dose of medication is injected intrathecally

- Spinal needle is removed

- Epidural catheter is threaded through the epidural needle

- Epidural infusion is started when spinal effect begins to diminish

Advantages and Disadvantages of CSE

Advantages

- Rapid onset of analgesia (3-5 minutes)

- High maternal satisfaction

- Reduced local anesthetic requirements

- Flexibility to extend analgesia duration

- Ability to convert to surgical anesthesia if needed

- May allow greater mobility during early labor (“walking epidural”)

Disadvantages

- More technically challenging

- Difficult to assess epidural catheter function until spinal component wanes

- Potential for increased risk of post-dural puncture headache

- Higher risk of pruritus due to intrathecal opioids

- Potential for significant hypotension with combined technique

- Requires additional expertise and equipment

Nursing Assessment After CSE

Following CSE placement, nurses should conduct regular assessments focusing on:

- Maternal vital signs (BP, HR, RR, SpO2) every 5 minutes for 20 minutes, then every 15-30 minutes

- Pain relief effectiveness using standardized scales (e.g., Visual Analog Scale)

- Sensory level assessment (dermatome level)

- Motor function assessment (ability to move legs, modified Bromage scale)

- Continuous fetal heart rate monitoring

- Signs of intrathecal opioid side effects (pruritus, nausea, respiratory depression)

- Urinary retention and bladder care

The CSE technique is particularly valuable in certain obstetric scenarios, such as rapidly progressing labor where immediate pain relief is needed, situations requiring careful titration of anesthetic level, and cases where early ambulation is desirable. It combines the best features of both spinal and epidural techniques, providing a versatile approach to obstetric anesthesia management.

5. Systemic Analgesia

While neuraxial techniques are the preferred method of obstetric anesthesia in many settings, systemic analgesia plays an important role in specific scenarios, such as when neuraxial techniques are contraindicated, unavailable, or declined by the patient. Systemic medications can provide reasonable pain relief, although typically less complete than neuraxial methods.

Parenteral Opioids

Parenteral opioids remain the most commonly used systemic analgesics in obstetric anesthesia, providing moderate pain relief during labor. They cross the placenta and can affect the fetus, requiring careful timing of administration relative to anticipated delivery time.

| Medication | Typical Dose | Onset (min) | Duration (hrs) | Neonatal Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fentanyl | 50-100 mcg IV | 1-2 | 1-2 | Short duration, minimal neonatal depression if delivery >1 hour after administration |

| Remifentanil | 0.25-0.5 mcg/kg IV PCA | <1 | 0.1-0.2 | Ultra-short-acting, rapid clearance by neonate, requires careful monitoring |

| Meperidine (Pethidine) | 25-50 mg IV, 50-100 mg IM | 5-10 (IV), 30-45 (IM) | 2-4 | Avoid within 4 hours of delivery; active metabolite (normeperidine) causes prolonged sedation |

| Morphine | 2-5 mg IV, 10-15 mg IM | 5-10 (IV), 20-40 (IM) | 3-6 | Increased risk of neonatal respiratory depression, avoid near delivery |

| Butorphanol | 1-2 mg IV/IM | 5-10 | 3-4 | Mixed agonist-antagonist, ceiling effect on respiratory depression |

Important Considerations

Opioids administered within 2-4 hours of delivery may cause neonatal respiratory depression requiring intervention. Have naloxone readily available when administering opioids to laboring patients approaching delivery. Maternal monitoring should include assessment of respiratory rate, sedation level, and oxygen saturation.

Patient-Controlled Analgesia (PCA)

Patient-controlled analgesia allows the parturient to self-administer small boluses of medication, providing greater autonomy and potentially more effective pain control compared to nurse-administered intermittent dosing.

Remifentanil PCA

Remifentanil PCA has emerged as a viable alternative when neuraxial analgesia is contraindicated or unavailable. Its ultra-short duration and rapid metabolism by plasma esterases make it uniquely suited for obstetric anesthesia, as it is quickly cleared from both maternal and fetal circulation.

- Typical settings: 0.25-0.5 mcg/kg demand dose with 1-2 minute lockout

- Advantages: Rapid onset and offset, minimal accumulation in fetus

- Disadvantages: Risk of maternal respiratory depression, requires 1:1 nursing

Nursing Protocol for Remifentanil PCA

- Continuous oxygen supplementation and pulse oximetry monitoring

- Dedicated 1:1 nursing attendance during administration

- No background infusion; demand doses only

- Assessment of respiratory rate and sedation level every 15-30 minutes

- Capnography if available

- Immediate access to resuscitation equipment

Non-Opioid Systemic Analgesia

Several non-opioid medications can be used alone or as adjuncts in obstetric anesthesia:

- Ketamine: Sub-dissociative doses (0.1-0.2 mg/kg IV) may provide analgesia with minimal psychotomimetic effects. Used primarily for brief procedures or as an adjunct.

- Dexmedetomidine: An alpha-2 agonist that provides sedation and analgesia without respiratory depression. Limited data in obstetrics but promising for specific scenarios.

- NSAIDs: Used primarily for post-cesarean pain management rather than during labor. Concerns include effects on fetal ductus arteriosus and platelet function.

- Acetaminophen: Safe during pregnancy and labor, used as an adjunct for mild pain or post-delivery.

Mnemonic: SAFER Systemic Analgesia Considerations

S – Side effects (maternal and fetal)

A – Appropriate timing relative to delivery

F – Fetal monitoring during administration

E – Emergency equipment available (naloxone, airway)

R – Respiratory monitoring essential

Clinical Pearl

When administering systemic opioids for obstetric anesthesia, consider timing carefully: the peak respiratory depressant effect on the neonate occurs when delivery happens at the time of peak maternal drug concentration. For short-acting agents like fentanyl, this window is relatively narrow (30-60 minutes), while longer-acting agents like morphine can affect the neonate for several hours after administration.

6. Inhalational Analgesia

Inhalational analgesia offers a non-invasive approach to obstetric anesthesia management. While less commonly used in some countries, it remains an important option in many birth settings worldwide, particularly where neuraxial techniques are unavailable or contraindicated.

Nitrous Oxide in Labor

Nitrous oxide (N2O) mixed with oxygen (typically 50:50 mixture, also known as Entonox) is the most widely used inhalational analgesic in obstetrics. It provides moderate analgesia with minimal side effects and is self-administered by the laboring patient.

Administration Technique

- Patient self-administers through a facial mask or mouthpiece

- Breathing should begin 30-50 seconds before the contraction for optimal effect

- Continuous use is avoided to prevent excessive sedation

- The device should have a demand valve system to prevent overdosage

- Scavenging system should be in place to minimize environmental exposure

Advantages

- Rapid onset (30-50 seconds) and offset

- Self-administered, giving patient control

- No significant effect on uterine contractility

- Minimal effect on the fetus due to low solubility

- No need for IV access or specialized personnel

- Can be used in any stage of labor

- Compatible with other analgesic methods

Limitations & Side Effects

- Moderate analgesia only (reduces pain by 30-50%)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Dizziness and drowsiness

- Risk of hypoxia if used without oxygen

- Environmental pollution concerns

- Potential vitamin B12 inactivation with prolonged use

- Contraindicated in vitamin B12 deficiency

Clinical Pearl

Nitrous oxide provides better analgesia when patients are properly instructed on its use. Teach patients to begin inhalation 30 seconds before the contraction starts and continue through the peak of the contraction. This maximizes analgesic effect due to the delay between inhalation and peak brain concentration.

Other Inhalational Agents

Historically, volatile anesthetics have been used for obstetric anesthesia in sub-anesthetic concentrations, although this practice has largely been replaced by other methods:

- Sevoflurane: Low concentrations (0.8%) have been studied for labor analgesia, showing some efficacy with minimal hemodynamic effects.

- Isoflurane: Has been used historically but concerns about uterine relaxation and maternal amnesia limit its application.

- Desflurane: Rarely used for labor analgesia due to airway irritation and strong odor.

Safety Considerations

Volatile anesthetics in high concentrations can cause uterine relaxation, potentially increasing blood loss during delivery. Additionally, they readily cross the placenta and can cause fetal depression. For these reasons, volatile agents are primarily reserved for general anesthesia during cesarean delivery rather than labor analgesia.

Nursing Responsibilities with Nitrous Oxide

- Provide clear instructions on proper timing and technique for self-administration

- Ensure equipment is functioning properly before use

- Monitor maternal oxygen saturation periodically

- Position patient appropriately to prevent aspiration if sedation occurs

- Ensure adequate room ventilation and scavenging systems

- Document duration of use and effectiveness

- Monitor for excessive sedation or adverse effects

Evidence Update

Recent systematic reviews indicate that nitrous oxide provides statistically significant pain relief compared to placebo or no treatment, although the magnitude of this effect is modest. Patient satisfaction is often high despite incomplete analgesia, likely due to the sense of control and mobility it provides. While maternal safety is well-established, more research is needed on potential subtle neurodevelopmental effects with prolonged exposure.

7. Regional Nerve Blocks

Regional nerve blocks offer targeted analgesia for specific aspects of labor and delivery pain. While not as comprehensive as neuraxial techniques, these blocks can be valuable adjuncts or alternatives in certain clinical scenarios within obstetric anesthesia practice.

Pudendal Nerve Block

The pudendal nerve block is the most commonly performed peripheral nerve block in obstetrics, providing anesthesia to the lower vagina, vulva, and perineum. It’s particularly useful for episiotomy, instrumental delivery, or repair of perineal lacerations.

Technique

The pudendal nerve can be blocked via transvaginal or transperineal approaches:

- Transvaginal approach: More common, involves palpating the ischial spine and injecting local anesthetic just below and posterior to it

- Transperineal approach: Needle insertion 1-1.5 cm posterolateral to the anus, advancing toward the ischial spine

- Local anesthetic: Typically 10 mL of 1% lidocaine or 0.25% bupivacaine per side

- Onset: 2-5 minutes for lidocaine, 5-10 minutes for bupivacaine

Key Point

The pudendal nerve block only addresses pain from the second stage of labor (perineal pain). It does not provide analgesia for uterine contractions or cervical dilation. In settings with limited resources or when neuraxial techniques are contraindicated, combining pudendal block with systemic analgesia can improve overall pain management.

Paracervical Block

The paracervical block targets the pain of cervical dilation during the first stage of labor by blocking the sensory fibers in the paracervical ganglion and uterovaginal plexus.

Technique

- Local anesthetic is injected into the vaginal fornices at the 3 and 9 o’clock positions

- Typical dose: 5-10 mL of 1% lidocaine or 0.25% bupivacaine per side

- Maximum depth of needle insertion should be limited to 3-5 mm

- Continuous fetal monitoring is essential during and after the procedure

Important Safety Concern

Paracervical blocks have been associated with fetal bradycardia in approximately 10-15% of cases, possibly due to fetal absorption of local anesthetic or uterine artery vasoconstriction. For this reason, they should be used cautiously and with continuous fetal monitoring. This technique is less commonly used in modern obstetric anesthesia practice.

Other Regional Nerve Blocks

| Block Type | Indication | Technique | Anesthetic Agent | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ilioinguinal-Iliohypogastric Block | Cesarean delivery incision pain | Injection 2cm medial and 2cm superior to the anterior superior iliac spine | 10-15 mL of 0.25-0.5% bupivacaine per side | Can reduce postoperative opioid requirements after cesarean delivery |

| Transversus Abdominis Plane (TAP) Block | Postoperative pain after cesarean delivery | Ultrasound-guided injection into the fascial plane between internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles | 15-20 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine per side | Provides somatic but not visceral analgesia; useful adjunct to multimodal analgesia |

| Quadratus Lumborum Block | Post-cesarean pain management | Ultrasound-guided injection at the lateral border of the quadratus lumborum muscle | 20-25 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine per side | May provide better visceral coverage than TAP block; emerging technique |

| Local Infiltration | Perineal repair, episiotomy | Direct infiltration of tissue planes | 10-20 mL of 1% lidocaine or 0.25% bupivacaine | Simple technique requiring minimal specialized equipment |

Clinical Pearl

TAP blocks performed at the conclusion of cesarean delivery can significantly reduce postoperative opioid requirements, particularly when intrathecal morphine is not used. Consider this technique as part of a multimodal analgesic approach for enhanced recovery after cesarean delivery protocols.

Nursing Considerations for Regional Blocks

- Monitor maternal vital signs before, during, and after block placement

- Assess fetal heart rate continuously when performing paracervical blocks

- Document the type of block, medication used, and patient response

- Monitor for signs of local anesthetic systemic toxicity (perioral numbness, metallic taste, visual/auditory disturbances, seizures)

- Evaluate effectiveness of the block and need for supplemental analgesia

- Observe for complications such as hematoma or infection at injection sites

8. General Anesthesia in Obstetrics

While neuraxial techniques are preferred for most cesarean deliveries, general anesthesia remains an important option in certain clinical scenarios. Understanding the unique considerations of general anesthesia in the obstetric population is essential for safe practice.

Indications for Obstetric General Anesthesia

- Emergency situations requiring immediate delivery (e.g., severe fetal distress, placental abruption)

- Contraindications to neuraxial anesthesia (e.g., coagulopathy, infection at insertion site)

- Failed neuraxial anesthesia despite adequate attempts

- Patient preference or refusal of neuraxial techniques

- Certain maternal medical conditions (e.g., severe cardiac disease where hemodynamic control is paramount)

Mnemonic: CRASHES for Obstetric General Anesthesia Challenges

C – Crash induction (rapid sequence due to aspiration risk)

R – Rapid desaturation (decreased FRC, increased O2 consumption)

A – Airway difficulties (edema, difficult laryngoscopy)

S – Stomach full (increased aspiration risk)

H – Hemodynamic instability (aortocaval compression)

E – Exaggerated drug responses (decreased MAC)

S – Securing airway safely is priority

General Anesthesia Technique

- Preparation:

- Pre-oxygenation with 100% oxygen for at least 3 minutes or 8 vital capacity breaths

- Left uterine displacement to prevent aortocaval compression

- Non-particulate antacid (sodium citrate) administration

- Equipment check including difficult airway equipment

- Induction:

- Rapid sequence induction with cricoid pressure

- Thiopental (4-6 mg/kg) or propofol (2-2.5 mg/kg) for induction

- Succinylcholine (1-1.5 mg/kg) for muscle relaxation

- No mask ventilation prior to intubation (unless unable to intubate)

- Maintenance:

- Volatile agent (typically sevoflurane or isoflurane) at 0.5-0.75 MAC

- 50-70% nitrous oxide in oxygen (if used)

- Non-depolarizing muscle relaxant as needed

- After Delivery:

- Increase volatile agent concentration if needed

- Administer opioids (fentanyl 100-250 mcg or equivalent)

- Oxytocin administration (avoid bolus; use infusion)

- Consider additional analgesics for postoperative pain management

- Emergence:

- Extubate when fully awake with protective reflexes intact

- Position in semi-upright or lateral position if possible

- Continue oxygen supplementation and monitoring

Critical Concerns

Failed intubation occurs approximately 1 in 300 obstetric general anesthetics versus 1 in 2000 in the general population. All anesthesia providers should be familiar with the difficult airway algorithm and have immediate access to advanced airway equipment. Recent guidelines emphasize consideration of videolaryngoscopy as a first-line approach for obstetric airway management.

Awareness Under General Anesthesia

The incidence of awareness during general anesthesia is higher in obstetric patients (approximately 1:670 compared to 1:19,000 in the general surgical population). This increased risk is due to:

- Use of lower concentrations of volatile agents before delivery to minimize fetal depression

- Avoidance of benzodiazepines and other amnesia-inducing agents before delivery

- Rapid sequence induction without adequate time for anesthetic equilibration

- Hesitancy to administer opioids before delivery

- Higher MAC requirements in younger patients

Minimizing Awareness Risk

- Ensure adequate anesthetic depth before incision (minimum alveolar concentration [MAC] >0.7)

- Consider using processed EEG monitoring when available

- Administer amnestic medications after cord clamping

- Provide thorough preoperative counseling about the possibility of awareness

Clinical Pearl

When administering general anesthesia for cesarean delivery, consider using end-tidal anesthetic gas monitoring to ensure adequate anesthetic depth. Aim for an age-adjusted MAC value of at least 0.7 even before delivery, as this significantly reduces the risk of awareness without substantially increasing neonatal depression. After delivery, increase to 1.0-1.3 MAC.

Nursing Responsibilities in General Anesthesia

- Assist with patient positioning for optimal intubation conditions

- Ensure left uterine displacement is maintained throughout

- Monitor maternal vital signs and report significant changes

- Be prepared for neonatal resuscitation if needed

- Document timing of anesthetic induction, delivery, and recovery

- Monitor for postoperative complications including respiratory depression

9. Anesthetic Considerations for Different Delivery Scenarios

Different delivery scenarios present unique challenges for obstetric anesthesia management. Tailoring the anesthetic approach to specific clinical situations ensures optimal outcomes for both mother and baby.

9.1 Vaginal Delivery

Labor analgesia for vaginal delivery requires balancing effective pain relief with preservation of maternal mobility and pushing effort. Modern techniques aim to provide comfort while minimizing motor blockade.

Epidural Analgesia for Labor

Contemporary labor epidural analgesia uses low-concentration local anesthetic combined with opioid to provide effective pain relief with minimal motor blockade.

Common Medication Combinations:

- Bupivacaine 0.0625-0.125% with fentanyl 1-2 mcg/mL

- Ropivacaine 0.08-0.2% with fentanyl 1-2 mcg/mL

- Initial bolus followed by continuous infusion (typically 8-12 mL/hr)

- Patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) with background infusion plus demand doses

Epidural Management During Labor Stages

| Labor Stage | First Stage | Second Stage | Third Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goal | Contraction and cervical pain relief | Balance between pain relief and pushing effectiveness | Comfort during placental delivery and repairs |

| Concentration | Standard concentration | Consider reducing or maintaining | May increase for perineal repair if needed |

| Technique | Continuous infusion ± PCEA | May reduce infusion rate during pushing | Bolus if needed for repair |

| Considerations | Assess block level and symmetry | Evaluate pushing effectiveness | Prepare for possible instrumental delivery |

Important Point

Modern low-concentration epidural techniques have largely eliminated the need to discontinue the epidural during the second stage of labor. Studies have shown that continuing epidural analgesia during pushing does not significantly impact the mode of delivery or duration of the second stage when low concentrations are used.

Clinical Pearl

For patients experiencing difficulty with pushing efforts while maintaining adequate analgesia, consider implementing a “mini motor block” assessment. If a high degree of motor block is present (Bromage score 2-3), reducing the concentration or rate of epidural medication can restore pushing effectiveness while maintaining reasonable comfort.

9.2 Cesarean Delivery

Cesarean delivery requires surgical-level anesthesia that blocks both somatic and visceral pain pathways while maintaining maternal safety and comfort.

Neuraxial Anesthesia for Cesarean Delivery

Neuraxial techniques (spinal, epidural, or CSE) are the preferred approach for cesarean delivery, associated with lower maternal mortality and morbidity compared to general anesthesia.

| Technique | Medication & Dosing | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spinal |

|

|

|

| Epidural |

|

|

|

| CSE |

|

|

|

Management of Hypotension

Hypotension is the most common side effect of neuraxial anesthesia for cesarean delivery, occurring in up to 80% of cases without prophylaxis. Strategies to prevent and manage hypotension include:

- Fluid preloading/co-loading: Crystalloid (500-1000 mL) or colloid (500 mL)

- Left uterine displacement: 15-30° tilt or manual displacement

- Vasopressors:

- Phenylephrine: First-line agent (50-100 mcg bolus or 25-50 mcg/min infusion)

- Ephedrine: 5-10 mg bolus (second-line due to fetal acidosis risk with repeated doses)

- Norepinephrine: Emerging alternative (0.05-0.1 mcg/kg/min)

- Lower-dose techniques: Using minimum effective dose of local anesthetic

Special Consideration

For emergency cesarean deliveries requiring extension of labor epidural analgesia to surgical anesthesia, 2% lidocaine with epinephrine (1:200,000) and sodium bicarbonate (1 mEq/10 mL) provides the most rapid onset. A volume of 15-20 mL typically achieves adequate surgical anesthesia within 10-15 minutes.

9.3 Instrumental Delivery

Instrumental delivery (forceps or vacuum-assisted) requires adequate perineal anesthesia to ensure maternal comfort during the procedure.

Anesthetic Options

- Existing labor epidural: Ensure adequate sacral coverage with additional bolus if needed (5-10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine or 2% lidocaine)

- Pudendal nerve block: If epidural is not in place or inadequate sacral coverage

- Local infiltration: For minimal perineal discomfort during simple instrumental deliveries

- Spinal anesthesia: For cases requiring more extensive manipulation (rare)

Clinical Pearl

When assessing the adequacy of an epidural block for instrumental delivery, evaluate sacral dermatomes specifically. Testing sensation at S3-S4 (perineal region) is more predictive of comfort during instrumental delivery than testing at higher levels. If inadequate, a supplemental bolus targeting the sacral roots may be needed.

Nursing Considerations

During instrumental delivery with neuraxial anesthesia:

- Monitor maternal vital signs every 5 minutes

- Assess level and adequacy of block before procedure begins

- Position patient appropriately for delivery (typically lithotomy)

- Provide emotional support during procedure

- Monitor for excessive bleeding post-delivery

- Document anesthetic interventions and patient response

10. Complications and Management

Obstetric anesthesia carries specific risks and potential complications. Recognition, prevention, and management of these complications are critical aspects of safe practice.

Post-Dural Puncture Headache (PDPH)

PDPH occurs due to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage through the dural puncture site, causing intracranial hypotension. The incidence is 1-2% after epidural placement and up to 80% after accidental dural puncture with an epidural needle.

Clinical Presentation

- Postural headache: worse when upright, improved when supine

- Typically begins 24-48 hours after dural puncture

- Occipital/frontal location, often radiating to neck

- Associated symptoms: nausea, vomiting, auditory/visual disturbances

- Duration: typically self-limiting over 7-10 days if untreated

Nursing Interventions for PDPH

- Encourage bedrest in supine position

- Maintain adequate hydration

- Administer analgesics as prescribed

- Monitor for neurological changes

- Apply abdominal binder if recommended

- Document headache characteristics and response to treatment

- Provide patient education about the condition

Management

| Treatment Approach | Method | Efficacy | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Bedrest, hydration, caffeine (300-500 mg PO/IV), analgesics | Moderate; temporary relief | First-line therapy for mild cases |

| Epidural Blood Patch (EBP) | 15-20 mL autologous blood injected into epidural space | 70-90% success rate | Gold standard for moderate-severe PDPH |

| SPGB (Sphenopalatine Ganglion Block) | Topical local anesthetic application to nasal mucosa | Variable; 30-70% | Non-invasive option before EBP |

| Epidural Saline/Dextran | Epidural infusion of crystalloid | Limited; temporary relief | Rarely used in current practice |

Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity (LAST)

LAST results from excessive plasma concentration of local anesthetic, affecting the central nervous system and cardiovascular system. Pregnant patients are at increased risk due to reduced protein binding and enhanced cardiac sensitivity to local anesthetics.

Clinical Presentation

- Early CNS signs: Perioral numbness, metallic taste, light-headedness, visual/auditory disturbances

- Progressive CNS toxicity: Slurred speech, muscle twitching, seizures, unconsciousness

- Cardiovascular toxicity: Hypertension/tachycardia (early), followed by hypotension, conduction blocks, arrhythmias, asystole

LAST Management Protocol

- Stop local anesthetic administration

- Call for help and prepare 20% lipid emulsion

- Airway management and seizure suppression (benzodiazepines preferred)

- Lipid emulsion therapy:

- 1.5 mL/kg 20% lipid emulsion bolus

- 0.25 mL/kg/min continuous infusion

- Repeat bolus 1-2 times for persistent cardiovascular collapse

- Continue infusion until hemodynamic stability

- CPR if cardiac arrest occurs (high-quality chest compressions)

- Avoid vasopressin, calcium channel blockers, beta blockers, and high-dose epinephrine

- Consider ECMO in cases refractory to standard treatment

High Neuraxial Block

High or total spinal anesthesia occurs when local anesthetic spreads higher than intended in the subarachnoid space, affecting cardiorespiratory centers in the brainstem.

Risk Factors

- Unintentional intrathecal injection during intended epidural administration

- Excessive dose of intrathecal local anesthetic

- Previous administration of epidural local anesthetic

- Increased intra-abdominal pressure (e.g., obesity, term pregnancy)

- Positioning changes after spinal placement

Management

- Immediate airway management and ventilatory support

- Fluid resuscitation and vasopressor therapy (phenylephrine preferred)

- Consider left uterine displacement in pregnant patients

- Atropine for significant bradycardia

- Support ventilation until block recedes

- Reassurance to the conscious patient

Clinical Pearl

To differentiate high spinal from local anesthetic toxicity, assess motor function in the upper extremities. In high spinal, there is progressive ascending motor weakness, while in LAST, motor weakness may be preceded by seizure activity or altered consciousness without clear dermatomal pattern.

| Complication | Prevention | Recognition | Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological Injury | Avoid neuraxial anesthesia in patients with coagulopathy; gentle technique; stop if paresthesia | Persistent sensory or motor deficit beyond expected block duration | Immediate neurological consultation, imaging studies, steroids if inflammatory |

| Epidural Hematoma | Careful timing with anticoagulants; assess coagulation status | Back pain, progressive neurological deficit, bowel/bladder dysfunction | Immediate MRI, neurosurgical decompression within 8 hours |

| Epidural Abscess | Strict aseptic technique, avoid in systemic infection | Back pain, fever, progressive neurological symptoms, elevated inflammatory markers | MRI, broad-spectrum antibiotics, possible surgical drainage |

| Arachnoiditis | Avoid contaminated solutions and neurotoxic agents | Persistent burning pain, dysesthesias in lower extremities, neurogenic bladder | Supportive care, pain management, physical therapy, steroids |

11. Nursing Considerations and Responsibilities

Nurses play a critical role in the safe administration of obstetric anesthesia and monitoring of patients who receive it. Their responsibilities span pre-anesthetic assessment, care during anesthesia, and post-anesthetic monitoring.

Pre-Anesthetic Nursing Assessment

Before obstetric anesthesia administration, nurses should perform and document a comprehensive assessment:

- Medical and obstetric history

- Allergies and medication history

- Airway assessment

- Vital signs baseline

- Laboratory values (if available)

- Fetal status assessment

- Contraindications to specific anesthetic techniques

Care During Neuraxial Anesthesia Placement

- Preparation:

- Position patient appropriately (lateral decubitus or sitting)

- Support patient to maintain position during procedure

- Establish IV access if not already present

- Assist with aseptic technique and setup

- Prepare emergency medications and equipment

- During Procedure:

- Monitor maternal vital signs

- Monitor fetal heart rate (before, during, after) as appropriate

- Provide emotional support and coaching

- Assist with position adjustments as needed

- Document procedure details and patient response

- Immediate Post-Procedure:

- Monitor vital signs every 5 minutes for 15-20 minutes

- Assess block level and effectiveness

- Position patient to prevent aortocaval compression

- Administer fluids and medications as ordered

- Ensure fetal monitoring is continued as appropriate

Mnemonic: BLOCK for Post-Epidural Nursing Assessment

B – Blood pressure monitoring

L – Level of sensory block (dermatome)

O – Oxygen saturation

C – Comfort assessment (pain score)

K – Kinetic function (motor strength)

Ongoing Monitoring

| Assessment Parameter | Frequency | Normal Findings | Critical Findings Requiring Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Pressure | Q5min for 15-20min, then Q15-30min | Within 20% of baseline | SBP <90 mmHg or >20% drop from baseline |

| Heart Rate | Q5min for 15-20min, then Q15-30min | 60-100 bpm | HR <50 or >120 bpm |

| Respiratory Rate | Q15-30min | 12-20 breaths/min | RR <10 or >24 breaths/min |

| Oxygen Saturation | Continuous if on opioids, otherwise Q30-60min | >95% | <92% or downward trend |

| Sensory Level | Q30min initially, then Q1-2h | T10-T4 for labor; T4 for cesarean | Rising sensory level, especially above T4 |

| Motor Function | Q1-2h | Bromage 0-1 for labor epidural | Unexpected dense motor block or asymmetry |

| Pain Score | Q30min initially, then with contractions | VAS ≤3/10 with contractions | Persistent VAS >4/10 despite interventions |

| FHR Monitoring | Continuous during and after placement | Reassuring pattern | Category II or III tracing |

Clinical Pearl

When assessing motor function after neuraxial anesthesia, remember that some degree of motor weakness is expected. For labor epidurals, the modified Bromage scale helps standardize assessment: 0 = full movement, 1 = unable to straight leg raise but can flex knee, 2 = unable to flex knee but can flex ankle, 3 = no movement. Ideally, laboring women should have Bromage scores of 0-1 to maintain mobility.

Management of Complications

Hypotension Management

- Position patient on left side

- Increase IV fluid rate

- Administer oxygen if indicated

- Notify anesthesia provider

- Prepare vasopressors per protocol

Pruritus Management

- Reassurance (common and self-limiting)

- Cool compresses to affected areas

- Administer antihistamines if ordered

- For severe cases, low-dose naloxone

- Document location and severity

Urinary Retention

- Monitor bladder fullness

- Encourage voiding every 2-3 hours

- Assist to bathroom if permitted

- Consider intermittent catheterization

- Monitor post-void residuals

Inadequate Analgesia

- Assess block level and distribution

- Check catheter site and connections

- Document pain characteristics

- Notify anesthesia provider

- Prepare for potential catheter adjustment

Documentation

Comprehensive nursing documentation for obstetric anesthesia should include:

- Pre-procedure assessment and education provided

- Consent verification

- Position during placement

- Time of procedure start and completion

- Names of providers performing procedure

- Solutions and medications administered

- Maternal vital signs and responses

- Fetal heart rate before, during, and after procedure

- Level of sensory block achieved and timing

- Motor function assessment

- Pain scores and effectiveness of analgesia

- Any complications and interventions performed

- Patient’s psychological response

Nursing Education for Patients

Patient education is a key nursing responsibility for obstetric anesthesia success:

- Explain procedure and what to expect

- Teach optimal positioning for neuraxial placement

- Explain sensations patient might experience

- Discuss potential side effects and management

- Instruct on movement restrictions if applicable

- Explain monitoring procedures

- Provide guidance on reporting concerns

- Discuss pain assessment and management expectations

12. Pharmacology of Anesthetic Agents in Obstetrics

A thorough understanding of obstetric anesthesia pharmacology is essential for safe medication administration and monitoring potential maternal and fetal effects. Pregnancy alters drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, influencing dosing and safety considerations.

Local Anesthetics

Local anesthetics block sodium channels in neuronal membranes, preventing action potential propagation. They are the foundation of neuraxial anesthetic techniques in obstetrics.

| Agent | Class | Onset | Duration | Max Dose | Primary Use in Obstetrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lidocaine | Amide | Rapid | 1-1.5 hours | 4.5 mg/kg (plain) 7 mg/kg (with epi) |

Epidural for cesarean, pudendal block, local infiltration |

| Bupivacaine | Amide | Slow | 2-4 hours | 2 mg/kg (max 175 mg) | Epidural/spinal for labor and cesarean, standard for labor epidurals |

| Ropivacaine | Amide | Medium | 2-4 hours | 3 mg/kg (max 225 mg) | Labor epidural, less motor block than bupivacaine |

| Chloroprocaine | Ester | Very rapid | 30-60 min | 8-10 mg/kg | Emergency cesarean with epidural, rapidly metabolized |

| Levobupivacaine | Amide | Slow | 2-4 hours | 2 mg/kg | Similar to bupivacaine with less cardiotoxicity |

Clinical Pearl

To rapidly convert a labor epidural for emergency cesarean delivery, 3% chloroprocaine provides the fastest onset of surgical anesthesia (typically 5-10 minutes). While lidocaine with epinephrine and bicarbonate (3:1 lidocaine:bicarbonate ratio) offers a good alternative with onset in 10-15 minutes. Carbonation increases the non-ionized fraction of lidocaine, enhancing neuronal penetration.

Opioids in Obstetric Anesthesia

Opioids are commonly used in combination with local anesthetics for neuraxial anesthesia or as standalone systemic analgesics. They have distinct pharmacokinetic properties in the pregnant population.

| Agent | Neuraxial Dose | Systemic Dose | Duration | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fentanyl | Epidural: 50-100 mcg Intrathecal: 10-25 mcg |

IV: 50-100 mcg | Epidural: 2-4 hours Intrathecal: 1-3 hours IV: 30-60 min |

Rapid onset, minimal neonatal respiratory depression with appropriate timing |

| Sufentanil | Epidural: 10-20 mcg Intrathecal: 2.5-5 mcg |

IV: 5-10 mcg | Epidural: 2-4 hours Intrathecal: 2-4 hours IV: 30-45 min |

Higher potency than fentanyl, enhanced lipid solubility |

| Morphine | Epidural: 2-4 mg Intrathecal: 100-200 mcg |

IV: 2-5 mg IM: 5-10 mg |

Epidural: 12-24 hours Intrathecal: 12-24 hours IV: 3-4 hours |

Excellent for post-cesarean pain, delayed respiratory depression risk up to 24 hours |

| Remifentanil | Not used neuraxially | PCA: 0.25-0.5 mcg/kg/dose | 3-5 minutes | Ultra-short acting, rapidly metabolized by plasma esterases, minimal fetal transfer |

Important Safety Consideration

Neuraxial opioids can cause delayed respiratory depression, particularly morphine due to its hydrophilic properties. After intrathecal morphine, monitor respiratory rate and sedation level hourly for 24 hours. Have naloxone readily available for emergency reversal of significant respiratory depression.

Adjuvant Medications

- Epinephrine (1:200,000): Added to local anesthetics to prolong duration, reduce systemic absorption, and provide a vascular marker

- Clonidine: Alpha-2 agonist that prolongs analgesia duration when added to neuraxial anesthetics (75-150 mcg epidural)

- Sodium bicarbonate: Added to lidocaine to hasten onset by increasing the non-ionized fraction

- Dexamethasone: Emerging evidence supports its use for prolonging peripheral nerve blocks

Vasopressors and Emergency Medications

| Agent | Indication | Dosing | Mechanism | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenylephrine | First-line for neuraxial hypotension | 50-100 mcg IV bolus 25-75 mcg/min infusion |

Pure α1-agonist | Preferred in obstetrics; maintains uteroplacental perfusion; may cause reflex bradycardia |

| Ephedrine | Second-line vasopressor, bradycardia with hypotension | 5-10 mg IV bolus Max 30 mg |

Mixed α and β effects | Can cause fetal acidosis with repeated doses; increases HR |

| Norepinephrine | Alternative vasopressor | 0.05-0.1 mcg/kg/min | α > β effects | Emerging agent for obstetric hypotension; requires controlled infusion |

| Atropine | Bradycardia | 0.4-0.6 mg IV | Anticholinergic | For significant bradycardia (<50 bpm) causing hemodynamic compromise |

| Naloxone | Opioid-induced respiratory depression | 40-80 mcg IV titrated | Opioid antagonist | Titrate carefully; may precipitate pain if fully reversed |

Mnemonic: SALE of Local Anesthetic Toxicity

S – Stop injection of local anesthetic

A – Airway management and 100% oxygen

L – Lipid emulsion therapy (20% intralipid)

E – Epinephrine and CPR if cardiac arrest

Uterotonics

Understanding uterotonic medications is important in obstetric anesthesia practice, as they can have significant hemodynamic effects requiring anesthetic adjustment: