Parasites, Rodents & Vectors

Comprehensive Nursing Notes

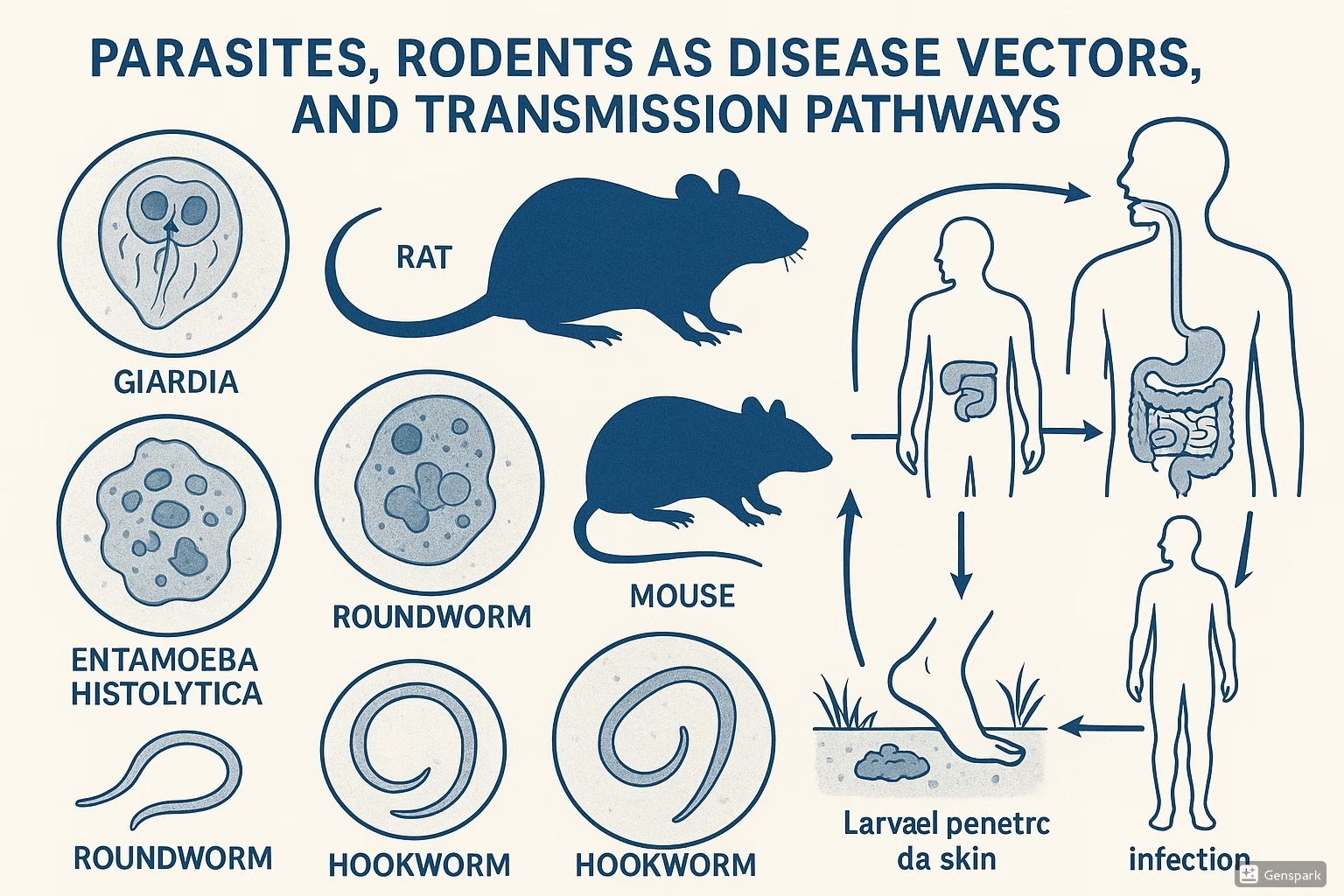

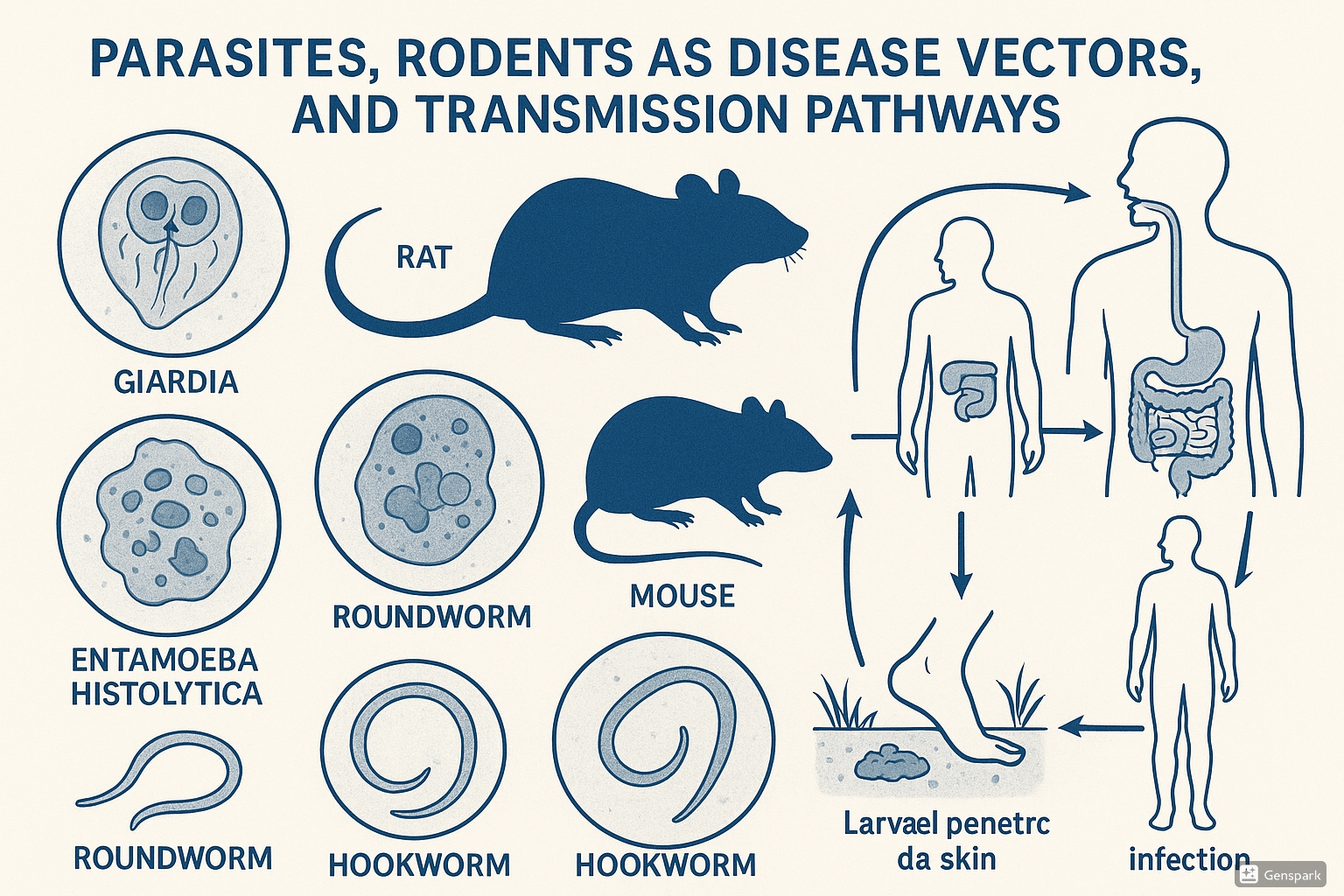

Figure 1: Parasites, Rodent Vectors, and Transmission Pathways

Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction to Parasites and Vectors

- 2. Parasites: An Overview

- 3. Rodents & Vectors

- 4. Transmission of Infection

- 5. Identification of Disease-Producing Microorganisms

- 6. Nursing Implementation

- 7. Prevention and Control Strategies

- 8. Mnemonics and Memory Aids

- 9. Clinical Case Studies

- 10. Conclusion

- 11. References

1. Introduction to Parasites and Vectors

Parasites are organisms that live on or in a host organism and get their food from or at the expense of the host. In the healthcare context, understanding parasites and their vectors is crucial for effective prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of parasitic diseases. These diseases represent a significant global health burden, affecting millions of people worldwide, particularly in resource-limited settings.

Parasitic infections range from relatively mild, localized conditions to severe systemic diseases that can be life-threatening. The diversity of parasitic organisms and their complex life cycles present unique challenges for healthcare professionals. Nurses, in particular, play a vital role in identifying risk factors, recognizing clinical manifestations, implementing preventive measures, and providing care for affected individuals.

This comprehensive guide focuses on the intricate relationship between parasites, their rodent vectors, and the mechanisms of disease transmission. By understanding these relationships, nursing professionals can better implement evidence-based practices for prevention, surveillance, and management of parasitic diseases.

2. Parasites: An Overview

Parasites that affect humans are diverse organisms that have evolved specialized adaptations to exploit their hosts for nutrition, reproduction, and survival. Understanding the basic classification and life cycles of parasites provides a foundation for comprehending their transmission, pathogenicity, and control strategies.

2.1 Types of Parasites

Parasites are broadly classified into three main categories based on their biological characteristics:

| Category | Characteristics | Examples | Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protozoa | Single-celled microscopic organisms that can multiply in humans. They can be transmitted through contaminated food/water, vectors, or direct contact. |

|

|

| Helminths | Multicellular worms with complex life cycles, often requiring intermediate hosts or specific environmental conditions. Further divided into nematodes (roundworms), cestodes (tapeworms), and trematodes (flukes). |

|

|

| Ectoparasites | External parasites that live on the skin or in the hair of their hosts. They may cause local irritation or serve as vectors for other pathogens. |

|

|

2.2 Parasite Life Cycles

Understanding parasite life cycles is essential for identifying critical points for intervention and control. Parasite life cycles can be categorized as:

- Direct life cycle: The parasite requires only one host to complete its development. Examples include Giardia lamblia and Ascaris lumbricoides.

- Indirect life cycle: The parasite requires multiple hosts (intermediate and definitive hosts) to complete its life cycle. Examples include Plasmodium species (malaria) and Schistosoma species.

Basic Parasite Life Cycle Patterns

Direct Life Cycle

- Parasite infects definitive host

- Development and maturation within host

- Reproduction and production of infective forms

- Shedding of infective forms into environment

- Transmission to new host (via ingestion, penetration, etc.)

- Cycle repeats

Indirect Life Cycle

- Parasite infects definitive host

- Development and reproduction within definitive host

- Production of eggs/larvae shed into environment

- Eggs/larvae infect intermediate host(s)

- Development of different life stages in intermediate host(s)

- Transmission to definitive host

- Cycle repeats

Key stages in parasite life cycles include:

- Infective stage: The form of the parasite capable of establishing infection in a host

- Diagnostic stage: The form of the parasite commonly found in diagnostic specimens

- Reproductive stage: The form responsible for multiplying within the host

- Transmission stage: The form responsible for spreading to new hosts

3. Rodents & Vectors

3.1 Characteristics

Vectors are organisms that transmit pathogens from one host to another. Rodents serve both as important reservoirs and vectors for many parasitic diseases affecting humans. Understanding their characteristics is essential for implementing effective control measures.

Vector Characteristics:

- Biological vectors: Organisms in which the pathogen undergoes development or multiplication before becoming infective to the recipient host (e.g., mosquitoes in malaria)

- Mechanical vectors: Organisms that transmit pathogens on their body parts without the pathogen undergoing development (e.g., flies carrying pathogens on their feet)

- Mobility: Ability to move between hosts, facilitating pathogen transmission

- Host specificity: Preference for feeding on certain host species

- Vector competence: Ability to acquire, maintain, and transmit pathogens

- Longevity: Survival period that influences transmission potential

Rodent Characteristics as Disease Reservoirs and Vectors:

- High reproductive rate: Rapid population growth leading to increased transmission potential

- Adaptability: Ability to survive in diverse habitats, including human dwellings

- Nocturnal behavior: Activity patterns that may affect human exposure

- Burrowing habits: Creating habitats that facilitate contact with soil-borne pathogens

- Feeding habits: Omnivorous diet that may include contaminated materials

- Urination/defecation patterns: Regular marking behaviors that can contaminate environments

- Mobility: Capacity to move across different environments, spreading pathogens

- Ectoparasite hosts: Serving as hosts for fleas, ticks, and mites that can be vectors themselves

3.2 Common Rodent Vectors

Several rodent species play significant roles in the transmission of parasitic diseases:

| Rodent Species | Associated Parasites/Diseases | Transmission Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Rattus norvegicus (Norway rat) |

|

|

| Rattus rattus (Black rat) |

|

|

| Mus musculus (House mouse) |

|

|

| Peromyscus species (Deer mice) |

|

|

| Microtus species (Voles) |

|

|

Mnemonic: “RODENT” for Common Rodent Vector Diseases

- R – Rickettsiosis (Murine typhus)

- O – Omsk hemorrhagic fever

- D – Dengue (rodents support mosquito populations)

- E – Echinococcosis

- N – Nipah virus

- T – Typhus, Toxoplasmosis

4. Transmission of Infection

4.1 Source & Portal of Entry

The source of parasitic infections refers to the reservoir from which the infectious agent originates, while the portal of entry is the pathway through which the parasite enters the host.

Common Sources of Parasitic Infections:

- Humans: Infected individuals serving as reservoirs for anthroponotic parasites (e.g., Enterobius vermicularis)

- Animals: Zoonotic reservoirs including domestic and wild animals (e.g., dogs for Echinococcus granulosus)

- Rodents: Primary reservoirs for various parasites (e.g., Yersinia pestis)

- Soil: Environmental reservoir for geohelminths (e.g., hookworm larvae)

- Water: Reservoir for waterborne parasites (e.g., Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium parvum)

- Food: Vehicle for transmission of various parasites (e.g., Taenia in undercooked meat)

Portals of Entry:

- Gastrointestinal tract: Entry via ingestion of contaminated food/water or soil (e.g., Ascaris, Giardia)

- Skin: Direct penetration through intact or broken skin (e.g., Schistosoma cercariae, hookworm larvae)

- Respiratory tract: Inhalation of airborne cysts or eggs (e.g., Echinococcus eggs)

- Mucous membranes: Direct contact with infectious agents (e.g., Acanthamoeba)

- Placenta: Vertical transmission from mother to fetus (e.g., Toxoplasma gondii)

- Bloodstream: Direct inoculation through vector bites (e.g., Plasmodium via mosquitoes)

4.2 Modes of Transmission

Parasites employ various modes of transmission to reach new hosts:

| Transmission Mode | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Vector-borne | Transmission via biological or mechanical vectors |

|

| Fecal-oral | Transmission through ingestion of fecally contaminated material |

|

| Direct contact | Transmission through physical contact with infected host or fomites |

|

| Foodborne | Transmission through ingestion of contaminated food |

|

| Waterborne | Transmission through ingestion of contaminated water |

|

| Soil-transmitted | Transmission through contact with contaminated soil |

|

| Vertical | Transmission from mother to offspring (prenatal or perinatal) |

|

4.3 Transmission Cycles

Understanding the transmission cycles of parasites is essential for identifying critical control points for intervention. The involvement of rodents in these cycles can be categorized as:

Rodent as Definitive Host:

In this scenario, the rodent harbors the adult form of the parasite, which reproduces sexually within the rodent. Examples include:

- Hymenolepis nana (dwarf tapeworm) – rodents serve as definitive hosts, but humans can also be infected directly

- Echinococcus multilocularis – rodents serve as intermediate hosts, with canids as definitive hosts

Rodent as Intermediate Host:

Here, the rodent harbors the larval or asexual stages of the parasite. Examples include:

- Toxoplasma gondii – rodents serve as intermediate hosts, with cats as definitive hosts

- Taenia taeniaeformis – rodents serve as intermediate hosts for this feline tapeworm

Rodent as Reservoir Host:

In this role, rodents maintain the parasite population in nature without necessarily being part of the direct transmission cycle to humans. Examples include:

- Leishmania species – rodents serve as reservoirs in certain geographic regions

- Trypanosoma cruzi – rodents serve as reservoir hosts in sylvatic cycles

Example: Plague Transmission Cycle

- Reservoir: Infected wild rodents harbor Yersinia pestis

- Vector acquisition: Fleas (Xenopsylla cheopis) feed on infected rodents

- Vector blockage: Bacteria multiply in flea gut, causing blockage

- Transmission to peridomestic rodents: Blocked fleas seek new hosts, including rats near human habitations

- Urban cycle: Infection spreads among rat populations

- Human infection: Fleas from infected rats bite humans

- Human-to-human transmission: Possible in pneumonic form via respiratory droplets

5. Identification of Disease-Producing Microorganisms

5.1 Diagnostic Methods

Accurate identification of parasites is crucial for appropriate treatment and control. Various diagnostic methods are employed depending on the parasite type and available resources:

Direct Microscopic Examination:

- Stool examination: Detection of intestinal parasites (ova, cysts, larvae)

- Blood smears: Identification of blood parasites (e.g., Plasmodium, Trypanosoma)

- Skin snips/scrapings: Detection of skin parasites

- Urine examination: Detection of Schistosoma haematobium eggs

Concentration Techniques:

- Sedimentation: Concentration of heavy parasite eggs (e.g., Schistosoma)

- Flotation: Concentration of lighter cysts and eggs (e.g., protozoan cysts)

- Kato-Katz technique: Quantification of helminth eggs

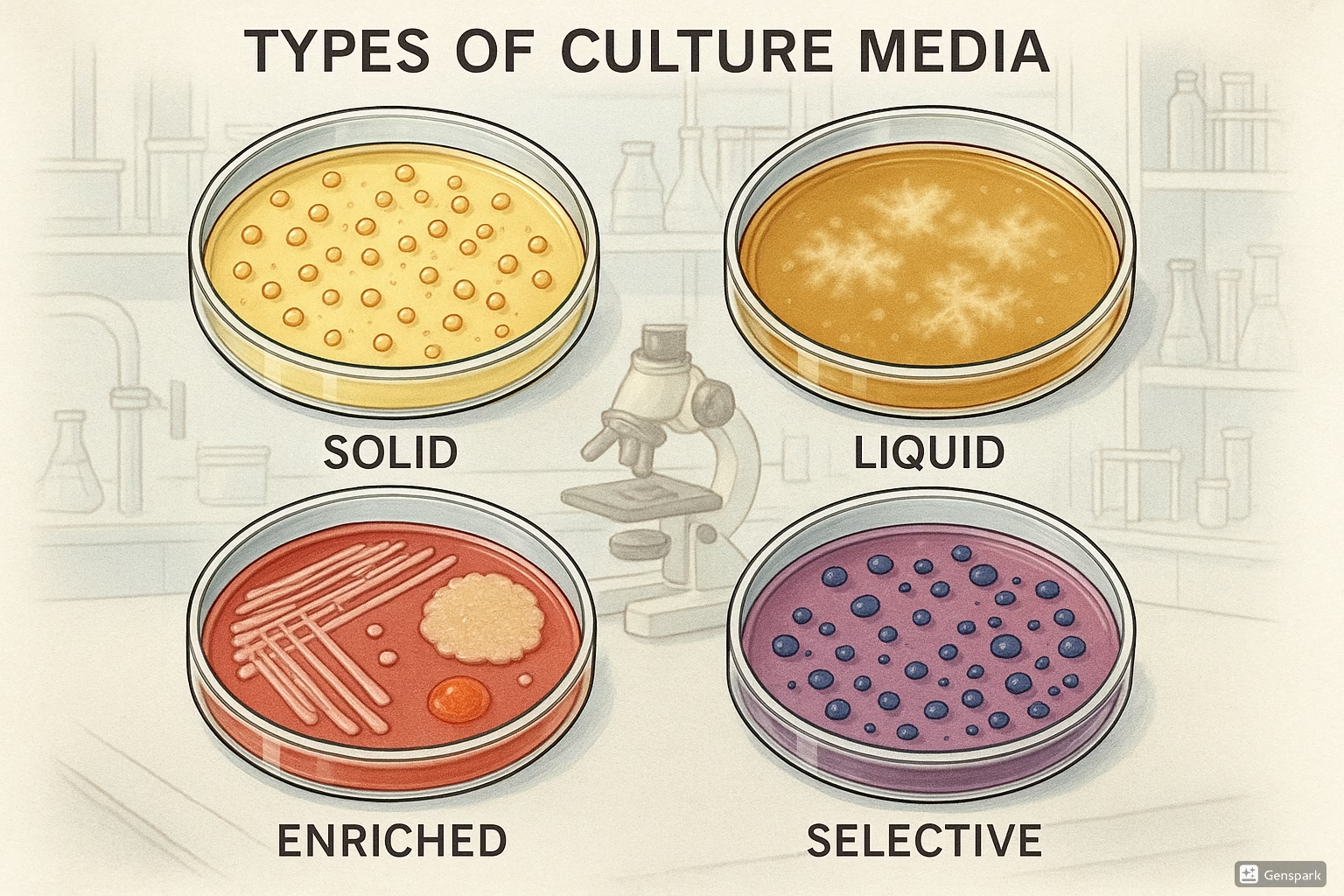

Culture Methods:

- Stool culture: For Strongyloides larvae

- Blood culture: For certain trypanosomes

- Tissue culture: For Leishmania and some amoebae

Immunological Methods:

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA): Detection of antibodies or antigens

- Immunofluorescence assay (IFA): Visualization of parasites or antibodies

- Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs): Field-applicable tests for parasites like malaria

Molecular Methods:

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR): Amplification of parasite DNA

- Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP): Field-applicable DNA detection

- Next-generation sequencing: Comprehensive parasite identification

Nursing Insight: Sample Collection

Proper sample collection is critical for accurate parasite identification:

- For stool samples, collect on 3 consecutive days to account for intermittent shedding

- For blood parasites, timing of collection may be crucial (e.g., microfilariae periodicity)

- Preserve samples appropriately to maintain parasite morphology

- Consider concentration techniques for low-burden infections

- Document travel history and exposures to guide diagnostic testing

5.2 Common Parasitic Diseases

Below are key parasitic diseases associated with rodent vectors or reservoirs:

| Disease | Causative Agent | Vector/Transmission | Clinical Features | Diagnostic Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plague | Yersinia pestis (bacteria) | Rat fleas (Xenopsylla cheopis) |

|

|

| Leptospirosis | Leptospira interrogans | Contact with rodent urine-contaminated water/soil |

|

|

| Chagas Disease | Trypanosoma cruzi | Triatomine bugs (rodents as reservoir) |

|

|

| Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome | Hantavirus | Inhalation of aerosolized rodent excreta |

|

|

| Murine Typhus | Rickettsia typhi | Rat fleas (Xenopsylla cheopis) |

|

|

| Lyme Disease | Borrelia burgdorferi | Ixodes ticks (mice as reservoir) |

|

|

Mnemonic: “PARASITE” for Key Diagnostic Features

- P – Proper specimen collection (timing, preservation)

- A – Analyze travel history and exposures

- R – Repeat testing may be necessary (intermittent shedding)

- A – Appearance and morphology are critical for microscopic identification

- S – Serology useful for chronic or past infections

- I – Immunoassays detect antigens or antibodies

- T – Technique matters (concentration methods enhance sensitivity)

- E – Expertise in microscopy improves detection rates

6. Nursing Implementation

Nurses play a crucial role in the prevention, identification, and management of parasitic diseases. Implementing the nursing process systematically can improve patient outcomes and prevent disease transmission.

6.1 Assessment

Comprehensive assessment is the foundation for effective nursing care of patients with parasitic infections:

History Taking:

- Travel history: Recent travel to endemic areas

- Environmental exposure: Contact with soil, contaminated water, or animals

- Living conditions: Housing quality, sanitation, presence of vectors

- Occupational exposure: Agricultural work, handling animals, waste management

- Dietary habits: Consumption of raw/undercooked food, water sources

- Recreational activities: Camping, hiking, swimming in freshwater

- Symptom onset: Timing, progression, and pattern of symptoms

- Household contacts: Similar symptoms in family members

Physical Examination:

- Skin assessment: Rashes, lesions, burrows (scabies), nodules, ulcers

- Gastrointestinal assessment: Abdominal tenderness, hepatosplenomegaly

- Cardiovascular assessment: Murmurs, signs of cardiomyopathy (Chagas)

- Respiratory assessment: Cough, dyspnea, respiratory distress

- Neurological assessment: Altered mental status, focal deficits, meningeal signs

- Lymphatic system: Lymphadenopathy, lymphedema

- General appearance: Pallor, jaundice, edema

Assessment Tool: “PARASITES”

A structured approach to assessing patients for parasitic infections:

- P – Patient demographics and risk factors

- A – Activities and exposures (occupational, recreational)

- R – Recent travel history

- A – Animal contact and vector exposure

- S – Symptoms (onset, duration, pattern)

- I – Intake (food, water sources)

- T – Timeline of illness progression

- E – Environmental factors (housing, sanitation)

- S – Similar illness in contacts

6.2 Nursing Diagnosis

Common nursing diagnoses for patients with parasitic infections include:

| Nursing Diagnosis | Related Factors | Defining Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Risk for Infection Transmission |

|

|

| Deficient Knowledge |

|

|

| Imbalanced Nutrition: Less than Body Requirements |

|

|

| Acute Pain |

|

|

| Impaired Skin Integrity |

|

|

| Activity Intolerance |

|

|

6.3 Nursing Interventions

Evidence-based nursing interventions for parasitic infections focus on treatment support, infection control, symptom management, and patient education:

Treatment Support:

- Medication administration: Administer antiparasitic medications as prescribed, monitoring for efficacy and adverse effects

- Medication education: Provide detailed instructions on dosing, timing, and potential side effects

- Treatment adherence: Develop strategies to enhance compliance with medication regimens

- Follow-up specimens: Collect post-treatment specimens to evaluate treatment efficacy

Infection Control:

- Isolation precautions: Implement appropriate isolation measures for communicable parasitic infections

- Hand hygiene: Reinforce proper handwashing techniques

- Environmental cleaning: Provide guidance on home disinfection when appropriate

- Vector control: Advise on measures to reduce vector populations in and around the home

- Contact investigation: Identify and notify potentially exposed individuals

Symptom Management:

- Pruritus management: Implement measures to reduce itching and prevent secondary infections

- Pain control: Administer analgesics as prescribed and implement non-pharmacological pain relief strategies

- Nutritional support: Address nutritional deficiencies and promote adequate intake

- Hydration: Monitor fluid balance, especially in patients with diarrheal illness

- Wound care: Provide appropriate care for cutaneous lesions

Patient Education:

- Disease process: Explain the parasite life cycle and transmission routes

- Prevention strategies: Teach specific preventive measures based on the parasite

- Environmental modification: Guide patients on creating environments less favorable to parasites and vectors

- Food safety: Educate on safe food preparation and handling

- Water treatment: Provide information on water purification methods

- Travel precautions: Advise on preventive measures for future travel

Priority Nursing Interventions for Vector-borne Parasitic Diseases

- Environmental Assessment: Evaluate patient’s living conditions for vector habitats

- Vector Control Education:

- Teach methods to eliminate standing water (mosquito breeding sites)

- Advise on rodent-proofing homes

- Demonstrate proper use of insecticides/repellents

- Guide on maintaining screens on windows and doors

- Personal Protection Guidance:

- Recommend appropriate clothing (long sleeves, pants)

- Teach proper application of insect repellents

- Advise on bed nets and their treatment with insecticides

- Guide on timing outdoor activities to avoid peak vector activity

- Community Notification: Coordinate with public health authorities for community-wide vector control if necessary

6.4 Evaluation

Evaluation of nursing interventions for parasitic infections should focus on these key outcomes:

- Infection resolution: Absence of parasites on follow-up testing

- Symptom management: Reduction or elimination of symptoms

- Prevention of complications: No evidence of secondary infections or complications

- Prevention of transmission: No new cases among contacts

- Knowledge acquisition: Patient demonstrates understanding of prevention strategies

- Behavior change: Patient implements appropriate preventive behaviors

- Functional status: Return to pre-illness activity levels

- Nutritional status: Improvement in nutritional parameters

Documentation Guidelines

Comprehensive nursing documentation for patients with parasitic infections should include:

- Detailed assessment findings, including risk factors and exposures

- Specific parasite identification when available

- Treatment administration details and patient response

- Infection control measures implemented

- Educational interventions provided and patient comprehension

- Symptom progression and resolution

- Follow-up testing results

- Communication with public health authorities if required

- Discharge planning and follow-up recommendations

7. Prevention and Control Strategies

Prevention and control of parasitic diseases require a multi-faceted approach addressing the parasite, vector, and host factors:

Primary Prevention Strategies:

- Vector control:

- Environmental management (elimination of breeding sites)

- Chemical control (insecticides, rodenticides)

- Biological control (predators, pathogens)

- Genetic methods (sterile insect technique)

- Personal protection:

- Protective clothing

- Insect repellents

- Bed nets (especially insecticide-treated nets)

- Window screens

- Environmental sanitation:

- Safe water supply

- Proper sewage disposal

- Food safety practices

- Waste management

- Rodent control:

- Exclusion (sealing entry points)

- Sanitation (eliminating food sources)

- Harborage reduction (removing nesting sites)

- Population control (trapping, rodenticides)

- Health education:

- Community awareness programs

- School-based education

- Risk communication

Secondary Prevention Strategies:

- Surveillance:

- Case detection and reporting

- Vector surveillance

- Reservoir host monitoring

- Early diagnosis:

- Screening high-risk populations

- Point-of-care testing

- Laboratory capacity strengthening

- Prompt treatment:

- Access to appropriate medications

- Treatment compliance support

- Mass drug administration in endemic areas

- Contact tracing:

- Identification of exposed individuals

- Screening of household members

- Preventive treatment when indicated

Integrated Parasite Control Strategy

- Assessment: Identify parasite species, vectors, reservoirs, and transmission patterns

- Planning: Develop targeted interventions based on local epidemiology

- Implementation: Apply multiple control methods simultaneously

- Environmental management

- Vector control

- Case management

- Community education

- Evaluation: Monitor effectiveness through:

- Disease surveillance

- Vector population monitoring

- Knowledge, attitude, and practice surveys

- Adaptation: Modify strategies based on evaluation results

Nursing Alert: Rodent Control Safety

When educating patients about rodent control, emphasize these safety precautions:

- Always use gloves when handling traps or removing dead rodents

- Disinfect areas contaminated with rodent urine/feces using appropriate disinfectants

- Avoid sweeping or vacuuming rodent droppings (can aerosolize pathogens)

- Keep rodenticides in tamper-resistant bait stations out of reach of children and pets

- Ventilate enclosed spaces before cleaning rodent-infested areas

- Dispose of dead rodents in sealed plastic bags

- Wash hands thoroughly after any activity involving potential rodent contact

8. Mnemonics and Memory Aids

Mnemonics can help nursing students remember key concepts related to parasites and vectors:

Mnemonic: “VECTORS” for Vector-borne Disease Assessment

- V – Visualization of vector (patient’s description or identification)

- E – Environment (exposure setting, endemic areas)

- C – Chronology of symptoms (incubation periods vary by pathogen)

- T – Travel history (recent and past travel to endemic regions)

- O – Outdoor activities (recreational, occupational exposure)

- R – Residential factors (housing conditions, proximity to vectors)

- S – Symptoms specific to vector-borne diseases

Mnemonic: “PARASITES” for Clinical Manifestations

- P – Pain (abdominal, muscle, joint)

- A – Anemia (from blood-feeding parasites)

- R – Rash or skin lesions

- A – Anorexia and weight loss

- S – Swelling (lymphadenopathy, edema)

- I – Intestinal symptoms (diarrhea, constipation)

- T – Temperature changes (fever patterns)

- E – Eosinophilia (common in helminthic infections)

- S – Systemic symptoms (fatigue, malaise)

Mnemonic: “PREVENT” for Parasite Prevention Education

- P – Protect with barriers (bed nets, screens, clothing)

- R – Repellents use correctly

- E – Environmental management (eliminate breeding sites)

- V – Verify water and food safety

- E – Exclude vectors from home (seal entry points)

- N – Notify authorities of infestations

- T – Treat infections promptly and completely

Mnemonic: “RODENT” for Rodent-borne Disease Risk Factors

- R – Rural or wilderness settings

- O – Occupational exposure (farmers, warehouse workers)

- D – Deteriorated housing conditions

- E – Exposure to rodent habitats (camping, hiking)

- N – Nesting materials present in living areas

- T – Trash/food availability attracting rodents

9. Clinical Case Studies

The following case studies illustrate the application of nursing knowledge in the management of parasitic diseases:

Case Study 1: Leptospirosis

Patient Profile: 28-year-old male agricultural worker presenting with fever, headache, myalgia, and conjunctival suffusion after recent flooding in the area.

Nursing Assessment:

- Occupational history reveals daily contact with potentially contaminated water

- Physical examination shows fever (39.2°C), conjunctival suffusion, mild jaundice, and right upper quadrant tenderness

- Laboratory findings include leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, elevated liver enzymes, and microscopic hematuria

Nursing Diagnoses:

- Risk for Fluid Volume Deficit related to fever and reduced oral intake

- Acute Pain related to inflammatory process

- Deficient Knowledge related to disease transmission and prevention

Nursing Interventions:

- Monitoring: Vital signs, intake and output, signs of worsening renal function

- Fluid Management: IV fluid administration as prescribed, oral rehydration when tolerated

- Medication Administration: Antibiotics as prescribed, antipyretics for fever

- Education: Prevention of leptospirosis through protective clothing, avoiding contaminated water

- Infection Control: Standard precautions, proper handling of urine

Evaluation:

Patient’s fever resolved after 5 days of antibiotic therapy. Liver and renal function tests returned to normal range. Patient demonstrated understanding of preventive measures, including wearing protective boots and gloves when working in potentially contaminated areas.

Case Study 2: Chagas Disease

Patient Profile: 45-year-old female immigrant from rural Central America with fatigue, palpitations, and dyspnea on exertion.

Nursing Assessment:

- Housing history reveals childhood residence in adobe house with thatched roof in endemic area

- Physical examination shows irregular heart rhythm, peripheral edema, and hepatomegaly

- Diagnostic findings include positive serology for T. cruzi, ECG abnormalities, and echocardiography showing dilated cardiomyopathy

Nursing Diagnoses:

- Decreased Cardiac Output related to Chagas cardiomyopathy

- Activity Intolerance related to cardiopulmonary dysfunction

- Anxiety related to chronic disease diagnosis and prognosis

- Risk for Caregiver Role Strain related to chronic illness management

Nursing Interventions:

- Cardiac Monitoring: Assessment of vital signs, heart rhythm, and signs of heart failure

- Medication Management: Administration of cardiac medications, antiparasitic therapy if prescribed

- Activity Management: Energy conservation techniques, gradual activity progression

- Education: Disease process, symptom management, when to seek medical attention

- Psychosocial Support: Addressing anxiety, connecting to support resources

- Family Education: Screen family members who shared same environmental exposures

Evaluation:

Patient’s cardiac symptoms stabilized with medication management. Activity tolerance improved with paced activities and rest periods. Patient verbalized understanding of chronic disease management and demonstrated adherence to treatment plan. Family members were referred for screening.

10. Conclusion

Parasites transmitted by rodents and other vectors present significant public health challenges worldwide. Nurses play a crucial role in the prevention, identification, and management of these diseases through their comprehensive approach to patient care.

Understanding the characteristics of parasites, their life cycles, and transmission mechanisms provides the foundation for effective nursing interventions. By implementing evidence-based practices in assessment, diagnosis, intervention, and evaluation, nurses can significantly impact individual patient outcomes and community health.

Key takeaways for nursing practice include:

- Detailed patient assessment focusing on exposure history and risk factors

- Recognition of the varied and sometimes subtle clinical presentations of parasitic diseases

- Implementation of appropriate infection control measures to prevent transmission

- Patient education on prevention strategies targeting specific transmission routes

- Collaboration with interdisciplinary teams and public health authorities for comprehensive management

- Advocacy for environmental and community-level interventions to reduce vector populations

As global travel increases and environmental changes affect vector distributions, nurses must maintain current knowledge of emerging and re-emerging parasitic diseases. Through education, vigilance, and evidence-based practice, nursing professionals contribute significantly to the control and prevention of these important public health threats.

11. References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Parasites. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/index.html

- World Health Organization. (2023). Vector-borne diseases. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/vector-borne-diseases

- Han, B. A., Schmidt, J. P., Bowden, S. E., & Drake, J. M. (2015). Rodent reservoirs of future zoonotic diseases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(22), 7039-7044.

- Heymann, D. L. (Ed.). (2022). Control of communicable diseases manual (21st ed.). American Public Health Association.

- Marquardt, W. C., Demaree, R. S., & Grieve, R. B. (2018). Parasitology and vector biology (3rd ed.). Academic Press.

- Garcia, L. S. (2022). Diagnostic medical parasitology (7th ed.). ASM Press.

- Gillespie, S. H., & Pearson, R. D. (2019). Principles and practice of clinical parasitology (2nd ed.). Wiley.

- Hotez, P. J., Fenwick, A., Savioli, L., & Molyneux, D. H. (2018). Rescuing the bottom billion through control of neglected tropical diseases. The Lancet, 373(9674), 1570-1575.

- NANDA International. (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023 (12th ed.). Thieme.

- Bulechek, G. M., Butcher, H. K., Dochterman, J. M., & Wagner, C. M. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC) (7th ed.). Mosby.

- Moorhead, S., Swanson, E., Johnson, M., & Maas, M. L. (2018). Nursing outcomes classification (NOC): Measurement of health outcomes (6th ed.). Mosby.

- Maguire, J. H., & Walker, D. H. (2023). Tropical infectious diseases: Principles, pathogens and practice (4th ed.). Elsevier.