Hernias in Children

Comprehensive Nursing Notes

1. Introduction to Pediatric Hernias

A hernia occurs when an organ or tissue protrudes through a weak area in the surrounding muscle or connective tissue (fascia). In children, hernias are common and often congenital (present at birth) due to incomplete closure of natural openings during fetal development.

Key Points:

- Pediatric hernias affect about 1-5% of all children

- More common in premature infants (up to 30% in some studies)

- Males are affected more frequently than females (especially for inguinal hernias)

- Most pediatric hernias require surgical treatment

Prevalence of Different Hernia Types in Children

| Hernia Type | Prevalence | Male:Female Ratio | Typical Age of Presentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inguinal Hernia | 1-5% of children; up to 30% in premature infants | 9:1 | Infancy to early childhood |

| Umbilical Hernia | 10-20% of children | 1:1 | Birth to 4 years |

| Epigastric Hernia | 0.5-5% of children | 3:1 | 2-7 years |

| Femoral Hernia | <0.5% of all pediatric hernias | 1:2 (more common in females) | School age to adolescence |

| Diaphragmatic Hernia | 1 in 2,000-5,000 live births | 1:1 | Prenatal to early infancy |

2. Types of Hernias in Children

2.1 Inguinal Hernia

Inguinal hernias are the most common type of hernia in children, accounting for approximately 80% of all pediatric hernias. They occur when abdominal contents protrude through the inguinal canal.

Pathophysiology:

In males, inguinal hernias typically result from failure of the processus vaginalis to close completely. During fetal development, the testes descend from the abdominal cavity through the inguinal canal and into the scrotum. The processus vaginalis, a pouch of peritoneum, precedes the testis and normally obliterates after testicular descent. When it remains patent, it forms a potential space for abdominal contents to herniate.

In females, inguinal hernias are associated with the round ligament of the uterus and the canal of Nuck (the female equivalent of the processus vaginalis).

Figure 1: Anatomy of pediatric inguinal hernia showing the patent processus vaginalis

Classification:

- Indirect inguinal hernia: Most common (99% of pediatric inguinal hernias). Occurs when abdominal contents protrude through the internal inguinal ring and into the inguinal canal through a patent processus vaginalis.

- Direct inguinal hernia: Extremely rare in children. Occurs when abdominal contents protrude through a weakness in the posterior wall of the inguinal canal (Hesselbach’s triangle).

Risk Factors:

- Prematurity (increased risk by 7-10 times)

- Low birth weight

- Male gender

- Family history of inguinal hernia

- Conditions with increased intra-abdominal pressure:

- Chronic cough

- Constipation

- Ascites

- Ventriculoperitoneal shunt

- Connective tissue disorders (Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome)

- Cryptorchidism (undescended testicle)

- Cystic fibrosis

Clinical Presentation:

- Painless, reducible bulge in the groin that may extend into the scrotum or labia

- Bulge often appears during crying, coughing, or straining

- May disappear when the child is relaxed or lying down

- Occasionally painful if incarcerated or strangulated

- May cause irritability in infants

Red Flags for Incarceration:

- Firm, tender, non-reducible bulge

- Irritability, inconsolable crying

- Vomiting, abdominal distension

- Erythema or edema of overlying skin

- Scrotal swelling and discoloration (in males)

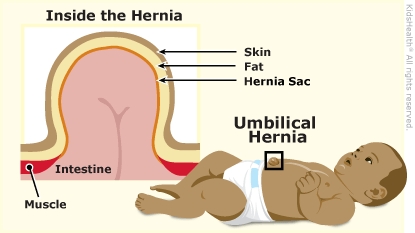

2.2 Umbilical Hernia

Umbilical hernias are the second most common type of hernia in children. They occur when abdominal contents protrude through a weakness in the abdominal wall at the umbilicus (belly button).

Pathophysiology:

During fetal development, the umbilical cord passes through an opening in the abdominal wall called the umbilical ring. This opening normally closes shortly after birth. When closure is incomplete, a weakness remains, allowing abdominal contents (usually intestine and omentum) to protrude through the defect.

Figure 2: Umbilical hernia showing protrusion at the umbilicus (belly button)

Risk Factors:

- Prematurity

- Low birth weight

- African American ethnicity (up to 5x higher incidence)

- Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome)

- Hypothyroidism

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome

Clinical Presentation:

- Painless, soft, reducible bulge at the umbilicus

- More prominent during crying, coughing, or straining

- Size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters

- Usually asymptomatic

- Rarely becomes incarcerated or strangulated

Natural History:

Unlike inguinal hernias, most umbilical hernias (90%) close spontaneously by age 4-5 years. The likelihood of spontaneous closure depends on:

- Size of the fascial defect (smaller defects more likely to close)

- Age at presentation (earlier presentation more likely to resolve)

Key Points for Umbilical Hernias:

- Generally benign condition

- High rate of spontaneous closure by age 4-5 years

- Low risk of complications (incarceration, strangulation)

- Surgical repair indicated if:

- Hernia persists beyond age 4-5 years

- Defect is large (>1.5 cm)

- Symptomatic (pain, incarceration)

- Progressive enlargement

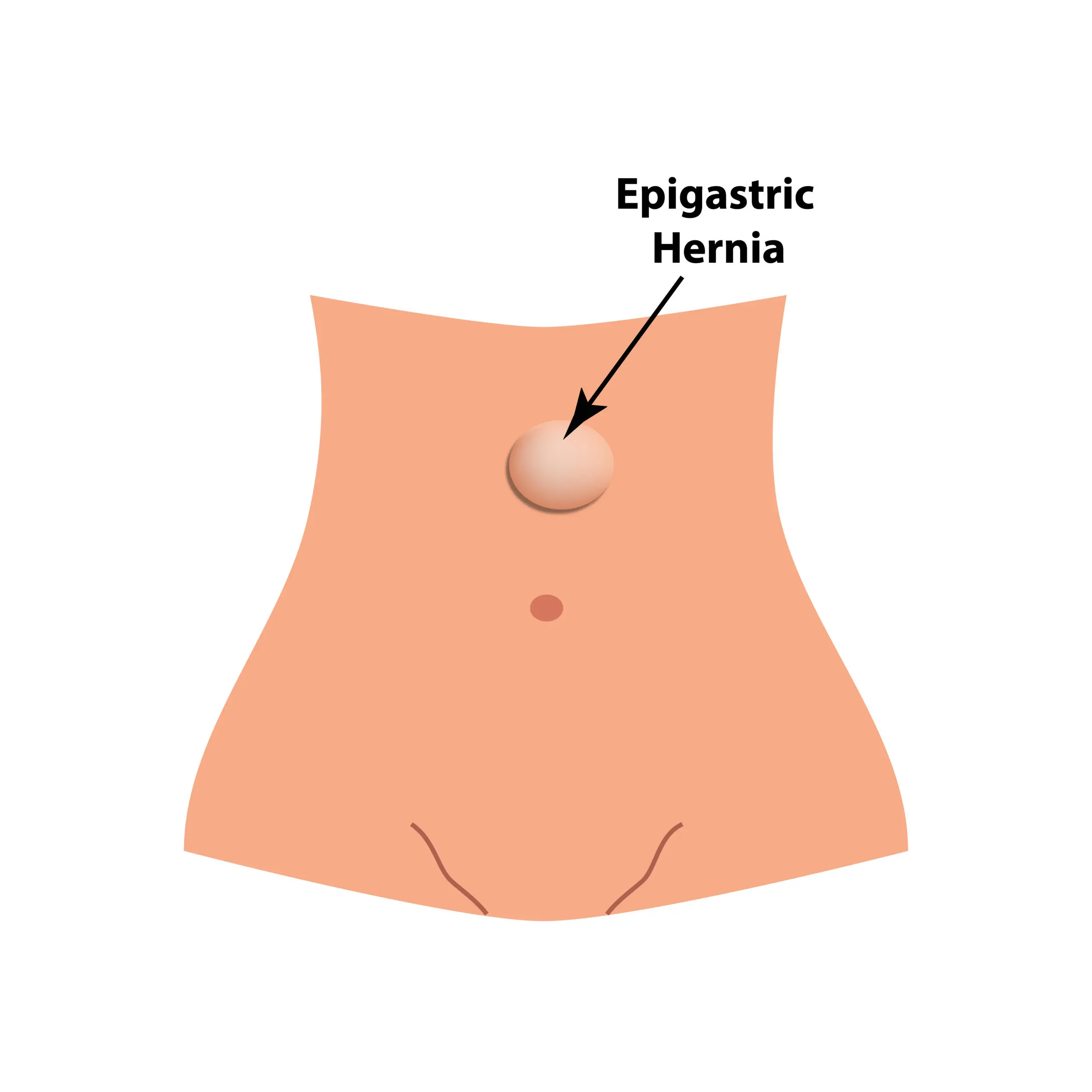

2.3 Epigastric Hernia

Epigastric hernias occur through the linea alba (midline) above the umbilicus and below the xiphoid process. They are the third most common type of hernia in children.

Pathophysiology:

Epigastric hernias result from a weakness or defect in the linea alba, which is the fibrous structure that runs down the midline of the abdomen. These defects allow preperitoneal fat or, rarely, abdominal contents to protrude through.

Figure 3: Epigastric hernia location in the midline above the umbilicus

Clinical Characteristics:

- Usually small (0.5-1 cm)

- Often asymptomatic, discovered incidentally

- May cause discomfort or pain, especially after eating or physical activity

- Typically contains preperitoneal fat rather than intestine

- Multiple defects may be present in 20-30% of cases

- Unlike umbilical hernias, epigastric hernias rarely close spontaneously

2.4 Femoral Hernia

Femoral hernias are rare in children, accounting for less than 0.5% of all pediatric hernias. They occur when abdominal contents protrude through the femoral canal, below the inguinal ligament.

Pathophysiology:

The femoral canal is a potential space located medial to the femoral vein, below the inguinal ligament. A hernia occurs when abdominal contents protrude through this space due to congenital or acquired weakness.

Clinical Characteristics:

- More common in girls than boys (unlike inguinal hernias)

- Often misdiagnosed as inguinal hernia

- Presents as a bulge below the inguinal ligament and lateral to the pubic tubercle

- Higher risk of incarceration due to narrow neck of hernia sac

- Often associated with connective tissue disorders

Important Note:

Femoral hernias are frequently misdiagnosed as inguinal hernias in children. This can lead to inappropriate surgical approach and recurrence. Always confirm the exact location of the hernia in relation to the inguinal ligament and pubic tubercle.

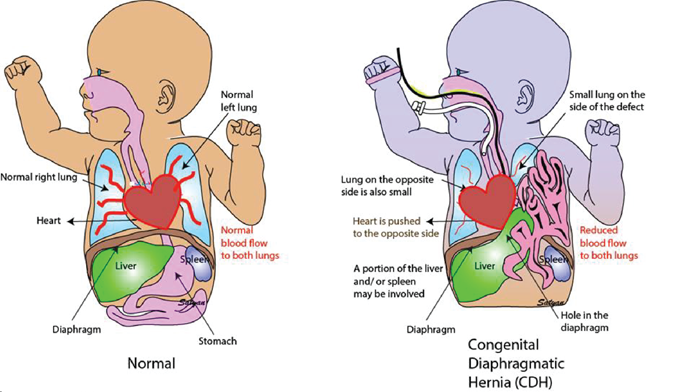

2.5 Diaphragmatic Hernia

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a serious birth defect where there is an abnormal opening in the diaphragm, allowing abdominal organs to move into the chest cavity during fetal development.

Pathophysiology:

CDH results from incomplete formation of the diaphragm during embryonic development (weeks 4-10 of gestation). The most common type is a posterolateral defect (Bochdalek hernia), accounting for 90% of cases.

Figure 4: Congenital diaphragmatic hernia showing abdominal organs in the chest cavity

Types:

- Bochdalek hernia: Posterolateral defect (90% of cases), more common on left side (80-85%)

- Morgagni hernia: Anterior defect (2% of cases), typically right-sided

- Central/septum transversum defect: Rare

Clinical Presentation:

- Often diagnosed prenatally through ultrasound

- Severe respiratory distress at birth (tachypnea, cyanosis, grunting)

- Scaphoid (concave) abdomen

- Barrel-shaped chest

- Breath sounds diminished or absent on affected side

- Heart sounds shifted away from affected side

- Difficulty feeding

Associated Complications:

- Pulmonary hypoplasia: Underdevelopment of lungs due to compression by herniated organs

- Pulmonary hypertension: Due to abnormal pulmonary vasculature development

- Cardiac anomalies: Present in 10-20% of cases

- Other congenital anomalies: Neural tube defects, chromosomal abnormalities, etc.

Critical Nursing Alert:

CDH is a medical emergency requiring immediate intervention. Bag-mask ventilation should be avoided or minimized as it can cause gastric distension and worsen respiratory compromise. Immediate intubation and placement of an orogastric tube are usually required.

3. Diagnosis of Pediatric Hernias

3.1 Clinical Evaluation

Diagnosis of pediatric hernias is primarily clinical, based on history and physical examination.

| Hernia Type | Key Physical Examination Findings | Assessment Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Inguinal Hernia |

|

|

| Umbilical Hernia |

|

|

| Epigastric Hernia |

|

|

| Femoral Hernia |

|

|

| Diaphragmatic Hernia |

|

|

3.2 Diagnostic Imaging

While most hernias are diagnosed clinically, imaging studies may be useful in certain situations:

Inguinal, Umbilical, Epigastric, and Femoral Hernias:

- Ultrasound: May be helpful when physical exam is equivocal, especially in:

- Obese children

- Children with undescended testes

- Differentiating hernia from hydrocele or lymphadenopathy

- Evaluating for incarceration or strangulation

- Abdominal X-ray: Generally not useful for diagnosis of external hernias, but may be indicated if bowel obstruction is suspected in case of incarceration.

Diaphragmatic Hernia:

- Prenatal ultrasound: Often identifies CDH between 16-24 weeks gestation

- Prenatal MRI: May be used to better define the defect and assess lung volume

- Chest X-ray: Shows intestinal loops in thoracic cavity, mediastinal shift

- CT scan: Rarely needed but may provide detailed anatomy before repair

- Echocardiogram: To assess cardiac function and rule out associated cardiac anomalies

Nursing Assessment Focus:

When assessing a child with a suspected hernia, nurses should document:

- Exact location, size, and characteristics of the bulge

- Reducibility (whether the bulge can be gently pushed back in)

- Presence of pain, tenderness, erythema, or skin changes

- Associated symptoms (vomiting, constipation, irritability)

- Factors that exacerbate the hernia (crying, coughing, straining)

- Duration of symptoms and any changes over time

4. Treatment and Management

4.1 Conservative Management

Umbilical Hernia:

- Observation is the standard approach for most umbilical hernias in children

- 90% close spontaneously by age 4-5 years

- Factors that predict spontaneous closure:

- Small defect size (<1.5 cm)

- Early age at presentation

- Regular follow-up to monitor for changes in size or symptoms

Common Myths to Address:

It’s important to educate parents that “belly button taping” or placing coins or buttons on the umbilical hernia does NOT help with closure and may cause skin irritation or damage.

Inguinal, Epigastric, and Femoral Hernias:

- Generally not managed conservatively due to risk of incarceration

- Surgery is the definitive treatment

- Sometimes brief observation may be considered in:

- Very premature infants until they reach appropriate weight

- Children with serious medical conditions precluding surgery

4.2 Surgical Management

| Hernia Type | Surgical Approach | Timing of Surgery | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inguinal Hernia |

|

|

|

| Umbilical Hernia |

|

|

|

| Epigastric Hernia |

|

|

|

| Femoral Hernia |

|

|

|

| Diaphragmatic Hernia |

|

|

|

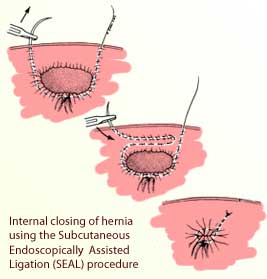

4.3 Management of Incarcerated Hernia

Initial Management:

- Place child in supine position with slight Trendelenburg (feet elevated)

- Apply ice pack to reduce swelling (10-15 minutes)

- Provide appropriate pain management

- Avoid repeated forceful attempts at reduction

- Gentle, sustained pressure for manual reduction

- If not reducible within 1-2 attempts, contact surgeon

Signs of Strangulation (Surgical Emergency):

- Severe pain and tenderness

- Erythema or dusky discoloration of overlying skin

- Fever

- Bilious vomiting

- Abdominal distention

- Lethargy or irritability

Sedation-Assisted Reduction:

- May be performed in the emergency department under sedation

- Common sedatives used:

- Midazolam

- Ketamine

- Propofol

- Nurse responsibilities:

- Monitor vital signs continuously

- Ensure resuscitation equipment available

- Document pre- and post-reduction assessment

- Educate parents about post-reduction monitoring

Post-Reduction Management:

- Observation for 2-4 hours after successful reduction

- Ensure child can tolerate oral intake

- Schedule urgent surgical repair (usually within 24-48 hours)

- Provide clear instructions to parents regarding warning signs

Figure 5: Surgical repair of pediatric inguinal hernia

5. Nursing Care of Children with Hernias

5.1 Preoperative Nursing Care

Assessment:

- Complete physical assessment, focusing on:

- Characteristics of the hernia (size, location, reducibility)

- Vital signs

- Hydration status

- Abdominal assessment

- Pain level (age-appropriate scale)

- Review medical history and identify risk factors:

- Prematurity

- Previous surgeries

- Congenital anomalies

- Conditions causing increased intra-abdominal pressure

- Evaluate nutritional status

- Assess family understanding and concerns

Interventions:

- Prepare child and family for surgery:

- Age-appropriate education about the procedure

- Tour of surgical area if possible

- Discuss expected postoperative course

- Implement preoperative fasting guidelines:

- Clear liquids: Up to 2 hours before surgery

- Breast milk: Up to 4 hours before surgery

- Formula/light meals: Up to 6 hours before surgery

- Complete preoperative checklist and documentation

- Administer preoperative medications as ordered

- Provide emotional support to child and family

5.2 Postoperative Nursing Care

| Assessment | Interventions | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Pain |

|

|

| Incision Site |

|

|

| Urinary Function |

|

|

| Nutrition and Hydration |

|

|

| Activity |

|

|

| Genital Assessment (for inguinal hernia repair) |

|

|

Mnemonic: “HERNIA” Care

Key nursing care priorities for pediatric hernia patients

- H – Hydration and nutrition assessment

- E – Educate child and family about condition and care

- R – Recognize complications early

- N – Note and manage pain appropriately

- I – Incision site care and monitoring

- A – Activity guidelines and restrictions

5.3 Discharge Planning and Home Care

Discharge Instructions:

- Wound care:

- Keep incision clean and dry

- Steri-strips typically fall off in 7-10 days

- Showers usually allowed after 48 hours; avoid tub baths for 5-7 days

- Pain management:

- Schedule for prescribed pain medications

- Signs of pain in younger children

- Non-pharmacological pain relief strategies

- Activity restrictions:

- No strenuous activity, heavy lifting, or sports for 2-4 weeks

- Return to school/daycare typically in 2-7 days

- Age-appropriate guidance for play

Warning Signs (When to Call Provider):

- Fever > 38.5°C (101.3°F)

- Increased redness, swelling, or drainage from incision

- Persistent or increasing pain not relieved by medication

- Inability to urinate within 8-12 hours after surgery

- Persistent vomiting or inability to tolerate fluids

- For boys with inguinal hernia repair: significant scrotal swelling or discoloration

Follow-up:

- Schedule for postoperative visit (typically 1-2 weeks)

- Importance of keeping follow-up appointments

- Contact information for questions or concerns

Family Education Checklist:

Ensure the following topics are addressed before discharge:

- Understanding of the procedure performed

- Wound care and bathing instructions

- Pain assessment and management

- Activity restrictions specific to age and type of hernia repair

- Diet recommendations

- Warning signs and when to seek medical attention

- Follow-up appointment details

- Return to school/daycare guidance

6. Nursing Diagnoses and Care Plans

| Nursing Diagnosis | Goals/Outcomes | Nursing Interventions | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Pain related to surgical incision, tissue manipulation, and inflammation as evidenced by verbal/nonverbal pain cues, irritability, or changes in vital signs |

|

|

|

| Risk for Infection related to surgical incision, immature immune system, and potential exposure to pathogens |

|

|

|

| Anxiety (child and/or parents) related to surgical procedure, hospitalization, and potential complications |

|

|

|

| Impaired Physical Mobility related to pain, surgical incision, and activity restrictions |

|

|

|

| Deficient Knowledge (parents) related to unfamiliarity with postoperative care and home management |

|

|

|

7. Complications and Special Considerations

7.1 Common Complications

Recurrence

Incidence: 1-5%

- Risk factors:

- Prematurity

- Technical errors during repair

- Wound infection

- Underlying connective tissue disorders

- Prevention:

- Proper surgical technique

- Adhering to activity restrictions

- Prevention of wound infection

- Management: Repeat surgical repair

Wound Infection

Incidence: 1-2%

- Risk factors:

- Poor hygiene

- Immunocompromised state

- Prolonged surgery

- Contamination during procedure

- Signs and symptoms:

- Erythema extending beyond incision margins

- Increased warmth, tenderness

- Purulent drainage

- Fever

- Management:

- Antibiotics (topical or systemic)

- Wound care

- Possible drainage if abscess forms

Testicular Complications (in males)

Incidence: 1-2%

- Types:

- Testicular atrophy

- Testicular ascent

- Vas deferens injury

- Risk factors:

- Incarcerated hernia

- Iatrogenic injury during surgery

- Extensive dissection

- Nursing implications:

- Assess testicular position and appearance

- Monitor for excessive scrotal swelling

- Educate parents about normal postoperative appearance

Urinary Retention

Incidence: 2-5%

- Risk factors:

- Male gender

- Spinal/caudal anesthesia

- Edema near bladder

- Pain

- Signs and symptoms:

- Inability to void within 8-12 hours after surgery

- Distended bladder

- Discomfort or restlessness

- Management:

- Encouragement to void

- Privacy

- Running water sounds

- Warm compress to lower abdomen

- Possible intermittent catheterization if needed

Incarceration and Strangulation

Medical Emergency

- Incarceration: Hernia contents become trapped in hernia sac

- Strangulation: Blood supply to trapped contents is compromised

- Highest risk:

- Infants under 6 months with inguinal hernia

- Femoral hernias

- Signs and symptoms:

- Firm, tender, non-reducible bulge

- Erythema of overlying skin

- Vomiting (may become bilious)

- Abdominal distention

- Irritability, inconsolable crying

- Lethargy in advanced cases

- Management:

- Gentle reduction attempt if recent incarceration

- Urgent surgical intervention if not reducible

- Fluid resuscitation

- NPO status

- Nasogastric decompression if bowel obstruction

7.2 Special Considerations in Specific Populations

Premature Infants:

- Higher risk of inguinal hernias (up to 30%)

- Increased incidence of bilateral hernias

- Timing of repair considerations:

- Some surgeons repair before NICU discharge

- Others wait until infant reaches certain weight (typically 2-2.5 kg)

- Risk of postoperative apnea if repaired before 60 weeks post-conceptional age

- Nursing implications:

- Careful monitoring for apnea and bradycardia post-repair

- Attention to thermoregulation

- Special considerations for pain assessment and management

- Careful attention to nutrition and hydration

Children with Connective Tissue Disorders:

- Increased risk of:

- Hernia development

- Recurrence after repair

- Bilateral hernias

- Conditions of concern:

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Marfan syndrome

- Osteogenesis imperfecta

- Nursing implications:

- Careful tissue handling during care

- Extended activity restrictions may be needed

- Vigilant monitoring for recurrence

- Education regarding increased lifetime risk

Children with Chronic Constipation or Cough:

- Increased risk of developing hernias due to increased intra-abdominal pressure

- Higher recurrence risk after repair

- Management strategies:

- Treat underlying condition aggressively

- Stool softeners to prevent constipation

- Cough suppression when appropriate

- Extended activity restrictions may be considered

Children with Ventriculoperitoneal Shunts:

- Increased risk of inguinal hernias due to increased intraperitoneal fluid

- Special considerations:

- Monitor shunt function before and after repair

- Coordinate care with neurosurgery team

- Monitor for signs of increased intracranial pressure

- Risk of shunt infection if peritoneal contamination occurs

8. Pediatric Hernias Concept Map

9. Key Takeaways and Clinical Pearls

Mnemonic: “HERNIAS” in Pediatric Patients

Key clinical points for pediatric hernia assessment and management

- H – History of hernia development (timing, progression, symptoms)

- E – Examine for reducibility and signs of incarceration

- R – Risk factors (prematurity, family history, connective tissue disorders)

- N – Note specific location (inguinal, umbilical, epigastric, femoral, diaphragmatic)

- I – Incarceration assessment (high-risk in infants under 6 months, requires urgent care)

- A – Age-specific management (observation vs. surgical repair)

- S – Support and education for families on home care and warning signs

Clinical Pearls

- Unlike adult hernias, pediatric inguinal hernias are almost always indirect (through the internal ring) and congenital in origin.

- Most umbilical hernias resolve spontaneously by age 4-5 years; observation is appropriate for asymptomatic hernias.

- Incarceration risk is highest in infants under 6 months with inguinal hernias; consider prompt surgical repair.

- Femoral hernias are frequently misdiagnosed as inguinal hernias in children; careful examination of the bulge in relation to anatomical landmarks is essential.

- The “silk glove sign” (feeling the hernia sac sliding between fingers) can help diagnose inguinal hernias in children even when no bulge is visible.

- Mesh is rarely used in pediatric hernia repairs, unlike in adults.

- Reducible inguinal hernias in otherwise healthy children can be repaired as an elective outpatient procedure.

- Contralateral exploration in unilateral inguinal hernias remains controversial; laparoscopy has increased the trend toward evaluation of the contralateral side, especially in girls.

Nursing Pearls

- For incarcerated hernias, place the child in a Trendelenburg position (feet elevated) with ice to the area before attempting gentle reduction.

- Avoid traditional “belly button taping” or placing coins on umbilical hernias; these practices are ineffective and potentially harmful.

- Scrotal edema is common after inguinal hernia repair in boys; educate parents about this expected finding.

- First void after surgery is an important milestone, especially after inguinal hernia repair due to proximity to the bladder.

- Use age-appropriate pain assessment tools; behavioral indicators may be more reliable than self-report in young children.

- Therapeutic play can be effective in preparing children for hernia surgery and reducing anxiety.

- Red flags for post-operative complications include: fever >38.5°C, increasing pain, redness/drainage from incision, persistent vomiting, and inability to void.

- Parents often need reassurance about activity restrictions; provide clear guidelines based on age and type of hernia repair.