Pediatric Lymphoma

Comprehensive Guide to Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma in Children

Introduction to Pediatric Lymphomas

Lymphomas are malignancies that originate from lymphocytes within the lymphatic system. They represent the third most common group of cancers in children and adolescents, accounting for approximately 10-15% of all childhood malignancies.

Definition:

Lymphomas are malignant neoplasms of the lymphoid system characterized by the proliferation of lymphocytes (B cells, T cells, or natural killer cells) arrested at various stages of development.

Lymphatic System

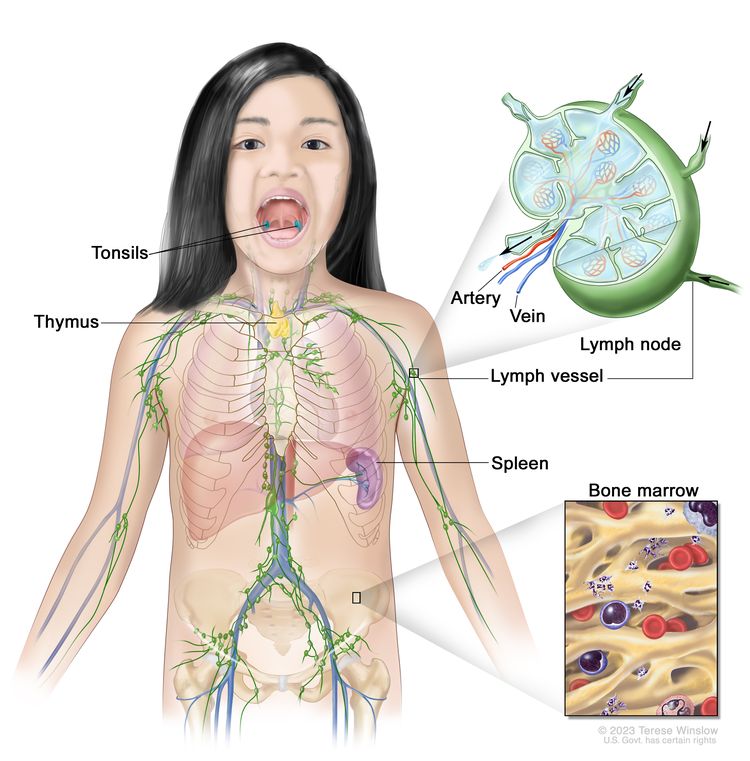

The lymphatic system is part of the body’s immune system and includes:

- Lymph nodes

- Lymphatic vessels

- Thymus

- Spleen

- Tonsils and adenoids

- Bone marrow

- Lymphoid tissue in the digestive tract

The lymphatic system includes lymph vessels, lymph nodes, spleen, thymus, tonsils, and bone marrow

Hodgkin vs. Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: Key Differences

| Feature | Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL) | Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) |

|---|---|---|

| Histologic Hallmark | Reed-Sternberg cells present | Reed-Sternberg cells absent |

| Age Distribution | Bimodal: adolescents (15-19 years) and adults >50 | Children of all ages, more common in younger children |

| Spread Pattern | Predictable, contiguous spread | Unpredictable, non-contiguous spread |

| B Symptoms | Common (fever, night sweats, weight loss) | Less common |

| Common Sites | Usually starts in lymph nodes of the neck; predictable spread | Often extranodal sites (GI tract, Waldeyer’s ring, skin) |

| Growth Rate | Usually indolent | Often aggressive in children |

| Cell Origin | Usually B-cell origin | B-cell, T-cell, or NK-cell origin |

| Survival Rate | Very high (>90% in children) | Variable by subtype, generally 85-90% |

Reed-Sternberg cell: The hallmark of Hodgkin lymphoma

Pediatric Hodgkin Lymphoma

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), formerly known as Hodgkin’s disease, is a malignancy of lymphoid tissue characterized by the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells. It accounts for approximately 7% of childhood cancers and has one of the highest cure rates among pediatric malignancies.

Pathophysiology

Hodgkin lymphoma arises from B lymphocytes in the germinal centers of lymph nodes. The malignant cells in HL are called Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells.

Reed-Sternberg Cell Characteristics:

- Large, abnormal lymphocytes

- Bilobed or multinucleated

- Prominent nucleoli (giving the classic “owl-eyes” appearance)

- Express CD15 and CD30 surface markers

- Usually of B-cell origin

In HL, the malignant cells make up only a small fraction (often <5%) of the total tumor mass. The remainder consists of a reactive inflammatory infiltrate, contributing to the characteristic appearance of the affected lymph nodes.

Reed-Sternberg cells with characteristic “owl eyes” appearance (multinucleated with prominent nucleoli)

Molecular Pathogenesis:

- Activation of NF-κB signaling pathway

- Constitutive JAK/STAT signaling

- Often associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, especially in developing countries

- Immune evasion through PD-1/PD-L1 upregulation

Epidemiology

Incidence

- ~7% of childhood cancers

- ~1,000 new cases in children and adolescents annually in the US

- Incidence increases with age in pediatric population

Age Distribution

- Rare in children <5 years

- Gradually increases throughout childhood

- Peak incidence in adolescents (15-19 years)

- Bimodal age distribution (second peak >50 years in adults)

Risk Factors

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection

- Family history (siblings have 3-7x higher risk)

- Immune dysregulation/immunodeficiency

- Male predominance in young children

- Balanced gender ratio in adolescents

Geographic Variations:

The association between HL and EBV infection varies geographically:

- Developed countries: ~20-40% of cases are EBV-positive

- Developing countries: up to 90% of cases are EBV-positive

This suggests different etiological factors may be involved in different populations.

Classification

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification divides Hodgkin lymphoma into two main types:

1. Classic Hodgkin Lymphoma (cHL)

Accounts for ~95% of pediatric HL cases, characterized by classical Reed-Sternberg cells.

Subtypes:

- Nodular Sclerosis (NS): Most common in adolescents (60-80% of pediatric HL), frequently involves mediastinum

- Mixed Cellularity (MC): More common in younger children, higher association with EBV

- Lymphocyte-Rich (LR): Rare in children, excellent prognosis

- Lymphocyte-Depleted (LD): Very rare in children, more aggressive

2. Nodular Lymphocyte-Predominant Hodgkin Lymphoma (NLPHL)

Accounts for ~5% of pediatric HL cases, distinct clinicopathological entity.

Features:

- Characterized by “popcorn” or “lymphocyte-predominant” cells (not classic RS cells)

- CD20+ (unlike classical HL)

- More common in males

- Usually presents with isolated peripheral lymphadenopathy

- Excellent prognosis, but higher rate of late relapses

- Small risk of transformation to aggressive NHL

MNEMONIC: Classic HL Subtypes

Nodular sclerosis is Most common, followed by Mixed cellularity, which is Less common than those but more common than Lymphocyte predominant.

“NeeM MyLL” (NSMC > LR & LD)

Clinical Features

Common Presentations

Painless Lymphadenopathy

Most common presentation, typically in the cervical region

Mediastinal Mass

Common in nodular sclerosis subtype, may cause respiratory symptoms

B Symptoms

Fever >38°C, night sweats, weight loss >10% in 6 months

Pruritus

Generalized itching, sometimes severe

Alcohol-Induced Pain

Pain in involved lymph nodes triggered by alcohol consumption

Fatigue

Common constitutional symptom

Site-Specific Symptoms

- Mediastinal involvement: Cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, superior vena cava syndrome

- Abdominal disease: Pain, fullness, early satiety, rarely obstructive symptoms

- Bone involvement: Pain, pathologic fractures (rare at presentation)

- CNS involvement: Extremely rare in pediatric HL

B Symptoms in Detail

Presence of B symptoms is important for staging and prognosis:

- Fever: Temperature >38°C without identifiable infection

- Night sweats: Drenching sweats requiring change of clothes/bedding

- Weight loss: Unexplained loss of >10% body weight in 6 months

Note: B symptoms occur in ~30% of pediatric HL patients and indicate more advanced disease.

Clinical Red Flags

- Rapidly enlarging, firm, non-tender lymph nodes

- Persistent lymphadenopathy (>4-6 weeks) without infection

- Supraclavicular lymphadenopathy (always concerning)

- Mediastinal widening on chest X-ray

- B symptoms in a child with lymphadenopathy

- Systemic symptoms disproportionate to apparent infection

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma requires an adequate tissue biopsy with histopathological confirmation.

Initial Evaluation

- Complete history: Focus on B symptoms, pruritus, lymphadenopathy duration

- Physical examination: Comprehensive lymph node assessment, hepatosplenomegaly

- Basic laboratory tests:

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- Comprehensive metabolic panel

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

- Uric acid

Diagnostic Procedures

- Excisional lymph node biopsy: Gold standard for diagnosis

- Core needle biopsy: May be sufficient if adequate tissue obtained

- Fine needle aspiration (FNA): Usually inadequate for primary diagnosis

- Bone marrow biopsy: For advanced stage disease

Note: When possible, a whole lymph node should be excised for proper evaluation of architecture and cell distribution patterns.

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

Classic HL Immunophenotype

| CD30 | Positive |

| CD15 | Usually positive |

| CD20 | Variably positive (weak) |

| CD45 | Usually negative |

| PAX5 | Weakly positive |

NLPHL Immunophenotype

| CD20 | Strongly positive |

| CD45 | Positive |

| CD30 | Usually negative |

| CD15 | Negative |

| BCL6 | Positive |

Imaging Studies for Staging

PET-CT Scan

- Standard for initial staging

- Superior to CT alone

- Identifies active disease

- Guides biopsy site selection

CT Scan

- Chest, abdomen, pelvis

- Identifies nodal and extranodal disease

- Provides anatomic detail

- Less sensitive than PET-CT

Additional Studies

- Chest X-ray: Initial assessment

- MRI: For CNS or spinal involvement (rare)

- Ultrasound: May help characterize peripheral nodes

Diagnostic Pearls

- Reed-Sternberg cells may be scarce in the specimen – thorough examination needed

- A definitive diagnosis requires both morphological and immunophenotypic confirmation

- Biopsy should be performed before starting steroids if lymphoma is suspected

- PET-CT is the most sensitive modality for assessing bone marrow involvement

- Interpretation by a pathologist experienced in pediatric lymphomas is essential

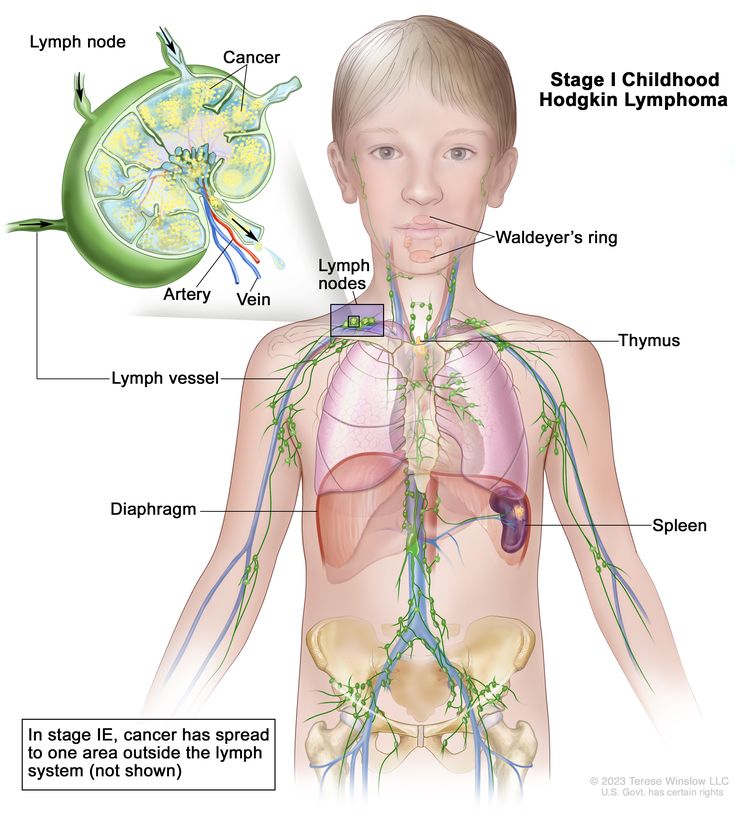

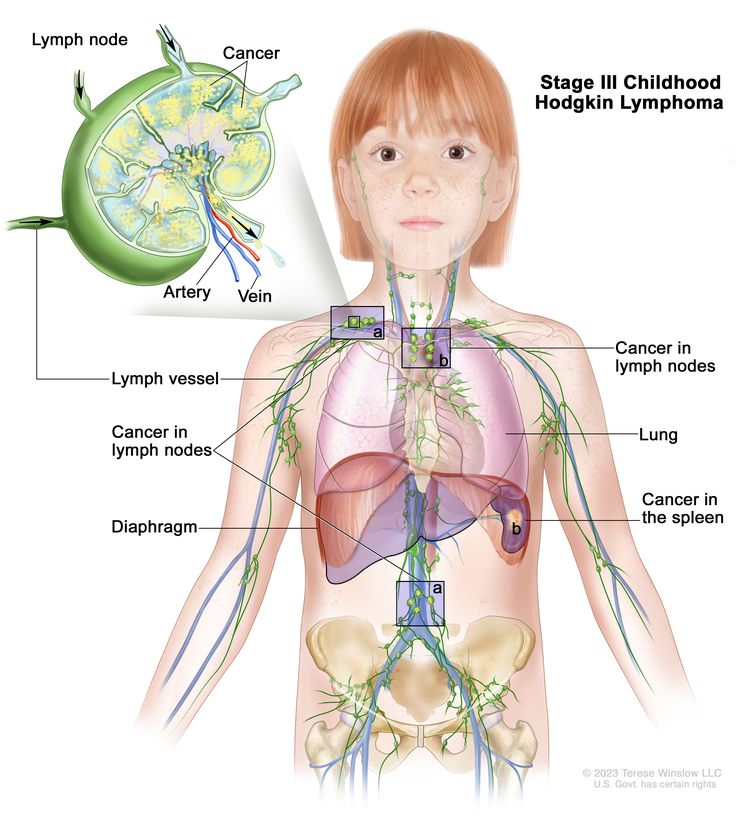

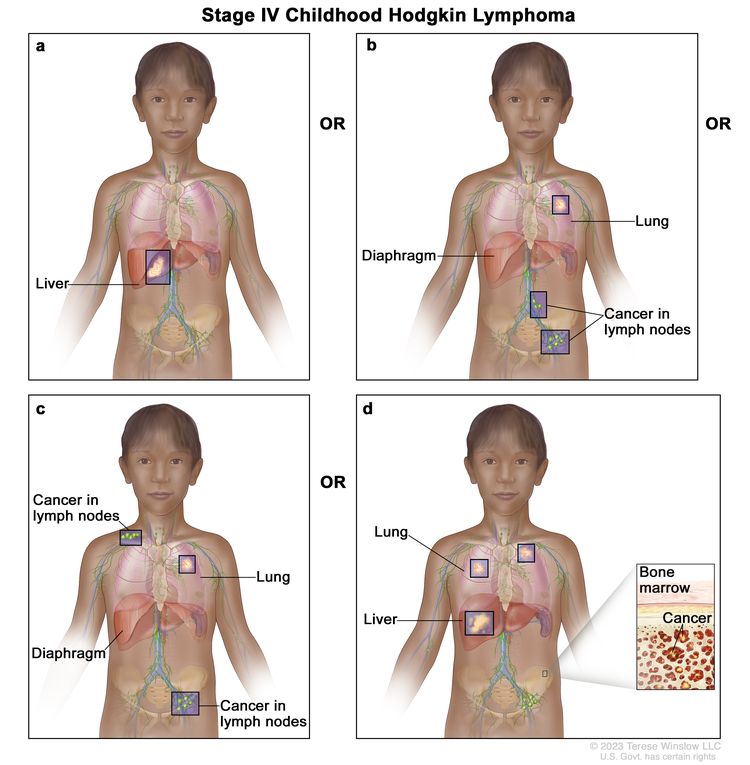

Staging

The Ann Arbor staging system with Cotswold modifications is used for staging pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma. Staging is critical for treatment planning and prognosis.

Ann Arbor Staging System

Stage I

Involvement of a single lymph node region or single extralymphatic site (IE)

Stage II

Involvement of two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm, or localized extralymphatic site and lymph nodes on same side of diaphragm (IIE)

Stage III

Involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm, which may include the spleen (IIIS) or localized extralymphatic site (IIIE)

Stage IV

Diffuse or disseminated involvement of one or more extralymphatic organs with or without lymph node involvement

Modifying Designations

- A: Absence of B symptoms

- B: Presence of B symptoms (fever, night sweats, weight loss)

- E: Extralymphatic involvement adjacent to nodal disease

- S: Splenic involvement

- X: Bulky disease (mediastinal mass >1/3 chest diameter or any mass >10 cm)

Example Staging Notation

Stage IIB X: Disease in two lymphatic regions on the same side of the diaphragm, with B symptoms and bulky disease

Stage IIIA S: Disease in lymphatic regions on both sides of the diaphragm including the spleen, without B symptoms

Risk Group Classification

For treatment planning, patients are stratified into risk groups based on stage, presence of bulk disease, and B symptoms:

| Risk Group | Disease Characteristics | Common Treatment Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Low Risk | Stage IA or IIA, no bulky disease | Reduced intensity chemotherapy ± low-dose radiation |

| Intermediate Risk | Stage IB, IIB, IIIA, or bulky mediastinal disease | Standard-dose chemotherapy ± radiation |

| High Risk | Stage IIIB or IV | Intensified chemotherapy ± radiation |

Treatment

Treatment of pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma is risk-adapted and has evolved toward maintaining high cure rates while minimizing long-term toxicities. The main treatment modalities include chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and targeted therapies for relapsed/refractory disease.

General Treatment Principles

The treatment approach for pediatric HL has evolved to:

- Reduce radiation exposure

- Minimize cumulative doses of cardiotoxic drugs

- Omit alkylating agents when possible to preserve fertility

- Use early response assessment to guide therapy intensity

- Tailor treatment intensity to risk group

Response Assessment

- Interim PET-CT: After 2-3 cycles of chemotherapy

- End-of-therapy assessment: 3-4 weeks after completing chemotherapy

- Deauville 5-point scale: Used to interpret PET findings (scores 1-2 indicate complete metabolic response)

Chemotherapy Regimens

| Regimen | Components | Common Use | Notable Toxicities |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABVE-PC | Adriamycin (doxorubicin), Bleomycin, Vincristine, Etoposide, Prednisone, Cyclophosphamide | Intermediate to high-risk disease | Cardiotoxicity, pulmonary toxicity, neutropenia |

| AVPC | Adriamycin, Vincristine, Prednisone, Cyclophosphamide | Low-risk disease | Cardiotoxicity, neuropathy |

| OEPA | Oncovin (vincristine), Etoposide, Prednisone, Adriamycin | Males, EuroNet protocols | Cardiotoxicity, neuropathy |

| COPP | Cyclophosphamide, Oncovin, Procarbazine, Prednisone | Alternative regimen, often with ABVD | Infertility, myelosuppression |

| ABVD | Adriamycin, Bleomycin, Vinblastine, Dacarbazine | Standard adult regimen, sometimes used in older adolescents | Pulmonary toxicity, cardiotoxicity |

Radiation Therapy

The role of radiation therapy has evolved significantly:

- Historical standard: Higher doses (35-44 Gy) and large fields

- Current approach: Lower doses (15-25 Gy) and involved-site radiation therapy (ISRT)

- Complete responders to chemotherapy may avoid radiation entirely in some protocols

- Considered more carefully in females due to breast cancer risk

Radiation Approaches

- Involved-field RT (IFRT): Targets involved nodal regions

- Involved-site RT (ISRT): More focused than IFRT, targets pre-chemotherapy disease extent

- Involved-node RT (INRT): Most focused, targets only initially involved nodes

- Proton therapy: May reduce dose to normal tissues, particularly for mediastinal disease

Risk-Adapted Treatment Approach

Low-Risk Disease (Stage I-IIA, no bulk)

2-4 cycles of chemotherapy (e.g., AVPC or ABVE-PC)

+ Radiation therapy (15-25 Gy) for incomplete responders

Expected 5-year EFS >90%

Intermediate-Risk Disease (Stage IIB, IIIA, bulky disease)

4-6 cycles of chemotherapy (e.g., ABVE-PC)

+ Radiation therapy (21 Gy) for bulky sites or incomplete response

Expected 5-year EFS 85-90%

High-Risk Disease (Stage IIIB, IV)

6-8 cycles of intensified chemotherapy (e.g., BEACOPP or escalated ABVE-PC)

+ Radiation therapy (21-36 Gy) for residual or initially bulky disease

Expected 5-year EFS 80-85%

NLPHL (Nodular Lymphocyte-Predominant HL)

Stage IA: Surgical excision alone or low-dose radiation

More advanced stages: CD20-directed therapy (rituximab) + chemotherapy

Expected 5-year EFS >95%

Relapsed/Refractory Disease

For the 10-15% of patients with relapsed or refractory disease:

- Salvage chemotherapy (e.g., ICE, GDP, or DHAP)

- High-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT)

- Radiation therapy if not previously given or to new sites

- Targeted therapies for resistant disease

Novel Therapeutic Approaches

- Brentuximab vedotin: Anti-CD30 antibody-drug conjugate

- Checkpoint inhibitors: Nivolumab, pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1)

- Rituximab: Anti-CD20 antibody (for NLPHL)

- CAR T-cell therapy: Under investigation in clinical trials

Treatment Pearls

- Response-adapted therapy is increasingly used to minimize treatment intensity while maintaining efficacy

- Interim PET assessment after 2 cycles can identify patients who may need therapy intensification

- Consider fertility preservation discussions prior to treatment, especially with alkylating agents

- Long-term follow-up is essential due to late effects of therapy

- Clinical trials should be considered when available, especially for high-risk or relapsed disease

Prognosis

Survival Rates

- Overall 5-year survival rate: >95%

- Event-free survival rate: 80-90%

- Cure rates across all stages: 85-95%

- Better outcomes compared to adult HL

Factors Associated with Better Outcomes

- Lower stage at diagnosis

- Absence of B symptoms

- Absence of bulky disease

- Rapid early response to therapy

- Nodular sclerosis or lymphocyte-predominant subtypes

Prognostic Factors

- Stage: Higher stage correlates with increased risk of relapse

- B symptoms: Presence indicates more aggressive disease

- Bulky disease: Associated with higher risk of relapse

- Response to initial therapy: Early complete response indicates better prognosis

- Histologic subtype: NLPHL has excellent prognosis but higher late relapse risk

Factors Associated with Poorer Outcomes

- Stage IV disease with multiple extranodal sites

- Elevated LDH and ESR at diagnosis

- Lymphocyte-depleted subtype (rare in children)

- Poor response to initial chemotherapy

- Short time to relapse (<12 months)

Follow-up Care

Surveillance Schedule

Typical follow-up after treatment completion:

- Every 2-3 months for the first 2 years

- Every 3-6 months for years 3-5

- Annually thereafter

- More frequent during the first 2 years when risk of relapse is highest

Surveillance Testing

- History and physical examination

- Basic laboratory tests (CBC, ESR, LDH)

- Imaging: Controversy exists regarding routine surveillance imaging

- Consider MRI instead of CT for surveillance when appropriate to reduce radiation exposure

- Late effects screening per Children’s Oncology Group guidelines

Pediatric Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in children is a diverse group of malignancies arising from lymphocytes at various stages of differentiation. It differs significantly from adult NHL in its biology, presentation, and treatment approaches.

Pathophysiology

Pediatric non-Hodgkin lymphoma arises from the malignant transformation of lymphoid cells at various stages of development. Unlike adult NHL, pediatric NHL is typically aggressive and rapidly growing.

Cell of Origin:

- B-cell origin: ~60% of pediatric NHL (Burkitt lymphoma, DLBCL)

- T-cell origin: ~35% of pediatric NHL (lymphoblastic lymphoma)

- NK-cell origin: ~5% of pediatric NHL

The distinction from Hodgkin lymphoma is the absence of Reed-Sternberg cells and the typically higher proportion of malignant cells within the tumor mass.

Molecular Pathogenesis:

- Burkitt lymphoma: t(8;14) translocation activates c-MYC oncogene (>90% of cases)

- Lymphoblastic lymphoma: Similar genetic alterations as acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- ALCL: t(2;5) translocation creating NPM-ALK fusion oncogene (~90% of cases)

- DLBCL: Various mutations including BCL6, BCL2 rearrangements

Associated Factors:

- Viral associations: EBV (Burkitt lymphoma), HHV-8 (rare)

- Immunodeficiency: Congenital or acquired (HIV, post-transplant)

- Genetic disorders: Ataxia-telangiectasia, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, X-linked lymphoproliferative disease

- Autoimmune conditions: Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis (for MALT lymphomas)

Growth Patterns and Behavior

Burkitt Lymphoma

- Extremely rapid growth (doubling time ~24 hours)

- High proliferation index (Ki-67 nearly 100%)

- Often involves abdomen, jaw (endemic form)

- High risk for tumor lysis syndrome

Lymphoblastic Lymphoma

- Aggressive growth pattern

- Often presents with mediastinal mass

- Propensity to spread to bone marrow and CNS

- Biologically similar to ALL

ALCL

- ALK-positive (in most pediatric cases)

- Often involves skin, lymph nodes, and bone

- Systemic symptoms common

- Can mimic other diseases (inflammatory and infectious)

Epidemiology

Incidence

- ~7-10% of childhood cancers

- ~800-1000 new cases in children/adolescents annually in the US

- Third most common childhood malignancy

Age Distribution

- Can occur at any age

- Incidence increases with age throughout childhood

- Median age 10 years

- Burkitt lymphoma: peaks at 5-10 years

- DLBCL: more common in adolescents

Gender Distribution

- Overall male predominance (M:F ratio 2-3:1)

- Burkitt lymphoma: strong male predominance (3-4:1)

- ALCL: slight male predominance

- Lymphoblastic lymphoma: male predominance (2:1)

Geographic Variations

- Endemic Burkitt lymphoma: Common in equatorial Africa, nearly always EBV-associated, typically involves the jaw

- Sporadic Burkitt lymphoma: Worldwide distribution, ~30% EBV-associated, typically involves abdomen

- Immunodeficiency-associated Burkitt lymphoma: Occurs in HIV-infected patients or post-transplant

Risk Factors for Pediatric NHL

- Primary immunodeficiency disorders:

- Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)

- Common variable immunodeficiency

- Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome

- Ataxia-telangiectasia

- Acquired immunodeficiency: HIV infection, post-transplant immunosuppression

- Prior EBV infection: Particularly for Burkitt lymphoma

- Prior malignancy treatment: Secondary NHL after chemotherapy/radiation

Classification

Pediatric non-Hodgkin lymphoma classification differs significantly from adult NHL. The WHO classification recognizes distinct pediatric entities, with over 90% of pediatric NHL cases falling into three major categories:

Major Types of Pediatric NHL

Mature B-cell NHL (40-45%)

- Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia: Aggressive, fast-growing. t(8;14) translocation activating c-MYC

- Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): More common in adolescents than young children

- Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma: Arises in the thymus, more common in adolescent females

Lymphoblastic Lymphoma (25-30%)

- Predominantly T-cell origin (85%)

- Less commonly B-cell origin (15%)

- Biologically similar to acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Often presents with mediastinal mass

- High risk for CNS involvement

Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (10-15%)

- T-cell or null-cell origin

- CD30+ (Ki-1) positive

- ALK+ in ~90% of pediatric cases

- t(2;5) translocation in most cases

- Often involves skin, bone, soft tissue

Less Common Pediatric NHL Types

- Pediatric-type follicular lymphoma: Different entity from adult follicular lymphoma, excellent prognosis

- MALT lymphoma: Rare in children, may be associated with H. pylori infection

- Primary CNS lymphoma: Extremely rare in immunocompetent children

- Peripheral T-cell lymphoma: Rare in children, generally aggressive

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: Very rare in children, includes mycosis fungoides

Immunodeficiency-Associated Lymphoproliferative Disorders

- Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD): Often EBV-driven

- HIV-associated NHL: Includes Burkitt lymphoma, DLBCL, and primary CNS lymphoma

- Lymphoproliferative disease associated with primary immunodeficiency: Various subtypes depending on underlying condition

Pediatric NHL Classification Mindmap

MNEMONIC: Major Types of Pediatric NHL

Burkitt, Lymphoblastic, Anaplastic Diffuse large B-cell

“BLADe” – Like a blade, these aggressive lymphomas cut through normal tissue rapidly

Clinical Features

Pediatric NHL typically presents with rapidly growing masses and often has extranodal involvement. Clinical presentation varies by subtype and anatomic location.

Common Clinical Presentations by Subtype

| NHL Subtype | Common Sites | Key Clinical Features |

|---|---|---|

| Burkitt Lymphoma |

|

|

| Lymphoblastic Lymphoma |

|

|

| ALCL |

|

|

| DLBCL |

|

|

Site-Specific Presentations

Mediastinal Mass

Cough, dyspnea, stridor, SVC syndrome, respiratory distress

Abdominal Disease

Abdominal pain, distention, nausea/vomiting, intussusception

Bone Involvement

Pain, pathological fractures, limited mobility

CNS Involvement

Headache, vomiting, cranial nerve palsies, altered mental status

Cutaneous Lesions

Nodules, plaques, ulcers, predominantly in ALCL

Bone Marrow

Fatigue, pallor, bleeding, fever, resembles leukemia

Systemic and B Symptoms

- Fever: Common, especially in ALCL and Burkitt lymphoma

- Weight loss: May be pronounced, especially with extensive disease

- Night sweats: Less common than in Hodgkin lymphoma

- Fatigue: Often present, may be related to anemia

- Decreased appetite: Common with abdominal involvement

Unique Presentations

- Endemic Burkitt: Jaw involvement (rather than abdomen)

- Immunodeficiency-associated NHL: Often more extensive, may involve unusual sites

- PTLD: Can involve allograft or extranodal sites, often EBV-driven

- Pediatric-type follicular lymphoma: Often localized cervical lymphadenopathy, excellent prognosis

Clinical Red Flags

- Very rapid growth of lymphadenopathy (days to weeks)

- Mediastinal mass with respiratory symptoms (medical emergency)

- Neurological symptoms suggesting CNS involvement

- Acute abdomen in a child with a mass

- Signs of tumor lysis syndrome (even prior to treatment)

- Abdominal distension with shifting dullness (ascites)

Diagnosis

Prompt diagnosis is critical due to the aggressive nature and rapid growth of most pediatric NHLs. Definitive diagnosis requires adequate tissue for histopathological, immunophenotypic, and often molecular studies.

Initial Evaluation

- History and physical examination: Assess timing of symptom onset, rapid growth suggests NHL

- Laboratory studies:

- Complete blood count with differential

- Comprehensive metabolic panel (including LDH, uric acid)

- Coagulation studies

- Tumor lysis labs (phosphorus, calcium, potassium)

Note: Elevated LDH is common in pediatric NHL and correlates with tumor burden. Very high levels are characteristic of Burkitt lymphoma.

Diagnostic Procedures

- Excisional biopsy: Preferred when feasible

- Core needle biopsy: May be adequate if sufficient tissue is obtained

- Fine needle aspiration: Generally insufficient as sole diagnostic procedure

- Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy: Required for staging

- Lumbar puncture: CSF cytology and flow cytometry, especially for Burkitt and lymphoblastic lymphoma

- Pleural/peritoneal fluid analysis: If effusions present

Pathology Studies

Histopathology

- Essential for subtype classification

- Architectural pattern assessment

- Cell morphology evaluation

- Mitotic index/proliferation rate

Immunophenotyping

- Immunohistochemistry on tissue

- Flow cytometry (blood, marrow, effusions)

- Lineage determination (B vs. T vs. NK)

- Subtype-specific markers

Molecular/Genetic Studies

- FISH for specific translocations

- Cytogenetic analysis

- PCR for clonality assessment

- Next-generation sequencing in select cases

Subtype-Specific Diagnostic Features

| NHL Subtype | Key Histologic Features | Immunophenotype | Molecular/Genetic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burkitt Lymphoma |

|

CD19+, CD20+, CD10+, BCL6+, CD5-, BCL2- | t(8;14), t(2;8), or t(8;22), all involving c-MYC |

| Lymphoblastic Lymphoma |

|

T-cell: TdT+, CD1a+, CD3+, CD4/8+ B-cell: TdT+, CD19+, CD79a+ |

Various, similar to ALL |

| ALCL |

|

CD30+, ALK+ (most pediatric cases), CD4+, EMA+, CD3 variable | t(2;5) NPM-ALK in ~80% |

| DLBCL |

|

CD19+, CD20+, CD79a+, Variable: BCL2, BCL6, CD10 | Various, incl. BCL6, BCL2 rearrangements |

Imaging Studies for Diagnosis and Staging

- Contrast-enhanced CT: Chest, abdomen, and pelvis for disease extent

- PET-CT: Superior to CT alone, especially for extranodal disease

- MRI: Preferred for CNS disease, spinal involvement, or soft tissue evaluation

- Ultrasound: May be helpful for initial evaluation of superficial masses

- Chest X-ray: Initial screening for mediastinal masses

Special Considerations

- Obtain complete staging studies prior to starting steroids if lymphoma is suspected

- Anticipate and prevent tumor lysis syndrome, especially with Burkitt lymphoma

- Mediastinal masses may require careful anesthetic planning for biopsy

- Multidisciplinary approach involving pediatric oncology, surgery, pathology, and radiology is essential

- Consider saving extra tissue for potential future studies or clinical trials

Staging

The staging of pediatric NHL differs from the Ann Arbor system used for Hodgkin lymphoma. Most pediatric protocols use the St. Jude/Murphy classification system, which better accounts for the disseminated nature and extranodal predilection of childhood NHL.

St. Jude/Murphy Staging System

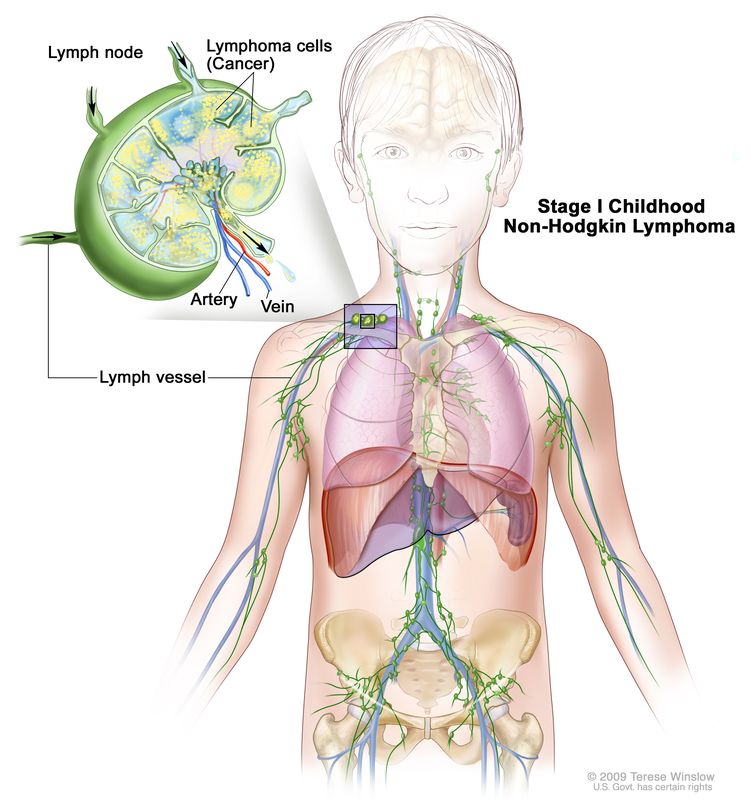

Stage I

Single tumor (extranodal) OR single anatomic area (nodal), excluding mediastinum or abdomen

Stage II

Single extranodal tumor with regional node involvement OR two or more nodal areas on the same side of the diaphragm OR primary gastrointestinal tract tumor (usually ileocecal) with or without associated mesenteric nodes, grossly completely resected

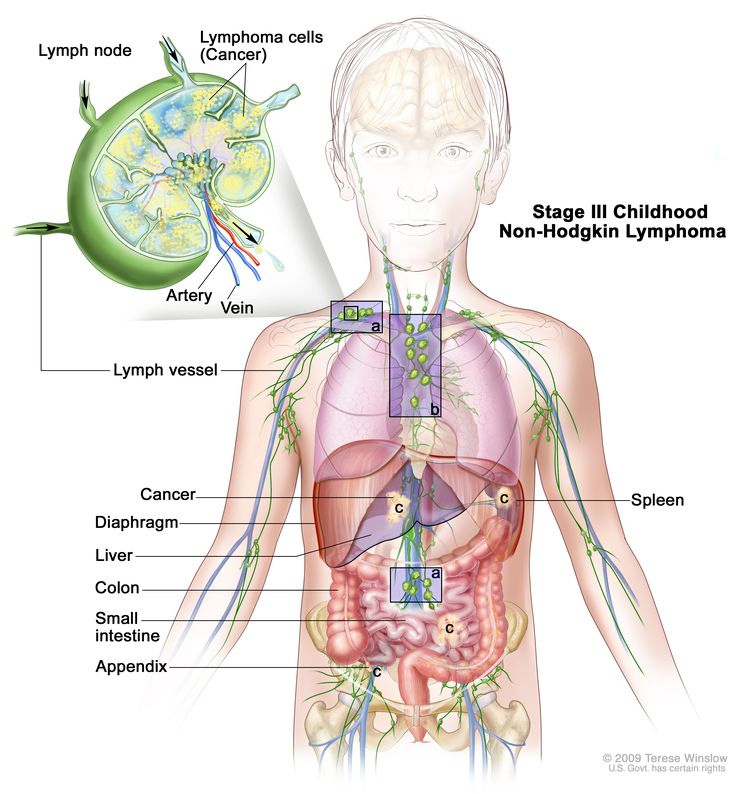

Stage III

Two single extranodal tumors on opposite sides of the diaphragm OR two or more nodal areas above and below the diaphragm OR primary thoracic tumor OR extensive primary intra-abdominal disease OR paraspinal or epidural tumors, regardless of other sites

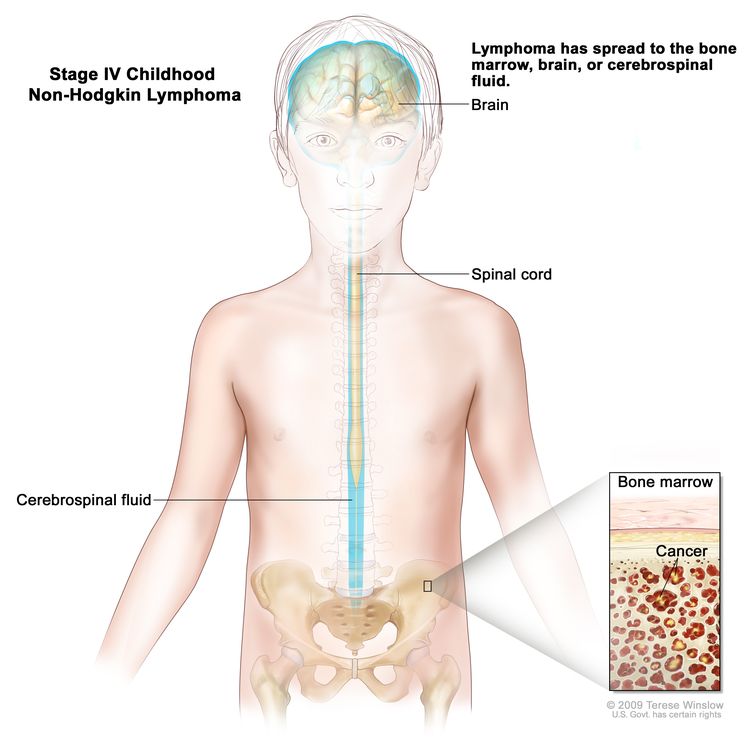

Stage IV

Any of the above with initial CNS and/or bone marrow involvement (≥25% blasts)

Additional Staging Considerations

CNS Staging

- CNS1: No evidence of CNS disease

- CNS2: CSF with <5 WBC/μL and cytologically positive OR intracerebral mass