Pediatric Tuberculosis: Comprehensive Nursing Notes

- 1. Introduction to Pediatric Tuberculosis

- 2. Epidemiology

- 3. Pathophysiology

- 4. Clinical Manifestations

- 5. Diagnosis and Identification

- 6. Nursing Management in Hospital Setting

- 7. Nursing Management in Home Setting

- 8. Prevention and Control Measures

- 9. Special Considerations

- 10. Case Study

- 11. References

1. Introduction to Pediatric Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is a major global health concern and remains one of the leading infectious causes of morbidity and mortality in children worldwide. Despite being preventable and curable, pediatric tuberculosis often goes undetected due to diagnostic challenges and non-specific symptoms that can mimic other common childhood illnesses.

As nursing professionals, understanding the unique aspects of tuberculosis in children is essential for early identification, proper management, and effective prevention. Children with tuberculosis present differently than adults, requiring specialized approaches to diagnosis and care. The nursing management of pediatric tuberculosis involves not only clinical interventions but also education, family support, and public health measures.

This comprehensive guide focuses on the identification, diagnosis, nursing management (both in hospital and home settings), and prevention/control of tuberculosis in the pediatric population. As we explore this topic, we’ll emphasize evidence-based practices and nursing-specific approaches to provide optimal care for children affected by tuberculosis.

Important Note:

Tuberculosis in children is often a sentinel event in the community, indicating recent transmission from an infectious adult. This makes pediatric tuberculosis both a clinical and public health priority.

2. Epidemiology

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 1.1 million children become ill with tuberculosis each year worldwide. However, this figure likely underestimates the true burden due to challenges in diagnosis and reporting.

Key Epidemiological Factors in Pediatric Tuberculosis:

- Age distribution: Children under 5 years of age are at the highest risk of developing disease after infection due to their immature immune systems.

- Close contacts: Most children acquire tuberculosis from household contacts, particularly parents or caregivers with infectious pulmonary TB.

- Geographic distribution: The highest burden of pediatric tuberculosis is found in regions with high TB prevalence, particularly in Asia and Africa.

- Risk factors: Malnutrition, HIV infection, young age, and close contact with infectious TB cases significantly increase the risk of TB infection and disease progression in children.

| Age Group | Risk After Infection | Common Presentation |

|---|---|---|

| Infants (<1 year) | 50% risk of progression to TB disease | Disseminated disease, TB meningitis |

| Young children (1-4 years) | 20-30% risk of progression | Pulmonary TB, lymphadenopathy |

| School-age (5-10 years) | 5-15% risk of progression | Often asymptomatic, pulmonary TB |

| Adolescents (>10 years) | 10-20% risk of progression | Adult-type cavitary disease |

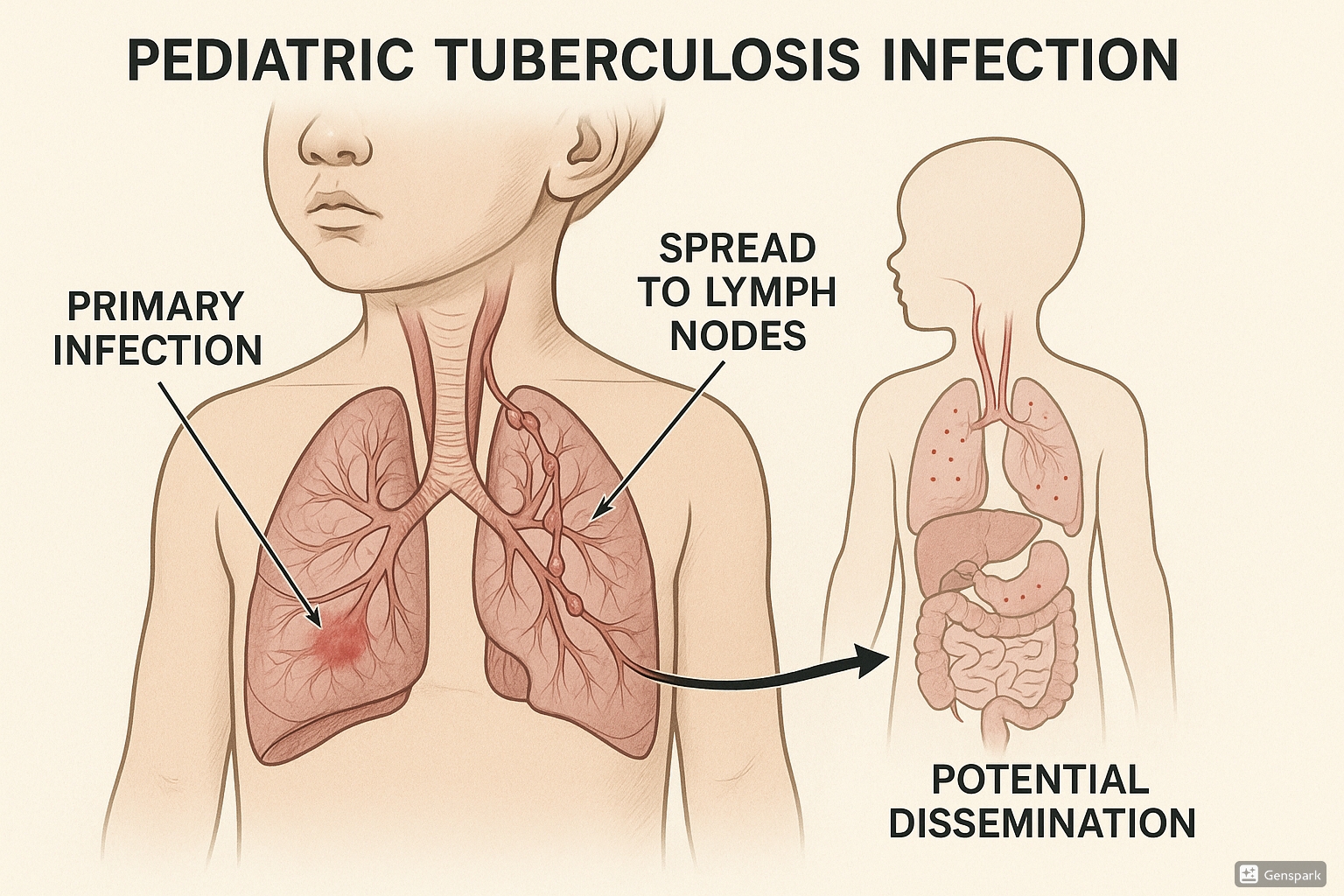

3. Pathophysiology

Understanding the pathophysiology of tuberculosis is crucial for nursing assessment and care planning. Tuberculosis is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, an aerobic, non-motile, non-spore-forming bacillus. In children, the pathophysiological process of TB infection and disease progression has several unique characteristics.

Stages of Tuberculosis Infection and Disease:

- Primary infection: When M. tuberculosis is inhaled, it establishes infection in the lungs. In children, this often occurs in the middle or lower lung fields.

- Primary complex formation: The initial focus of infection (Ghon focus) together with the involved regional lymph nodes forms the primary complex (Ghon complex).

- Latent TB infection (LTBI): In most children, the infection is contained by the immune system, resulting in latent tuberculosis infection without active disease.

- Progressive primary disease: In some children, especially those under 5 years or immunocompromised, the infection progresses to active disease.

- Dissemination: In young children, hematogenous spread of TB can occur more readily than in adults, leading to extrapulmonary TB, including TB meningitis and miliary TB.

Mnemonic: “PRIME TB”

To remember the pathophysiological progression of tuberculosis in children:

- P – Primary infection (inhalation of bacilli)

- R – Regional lymph node involvement

- I – Immune response (containment or progression)

- M – Multiplication (bacterial replication)

- E – Expansion or encapsulation

- T – Tissue destruction

- B – Bacterial dissemination (in severe cases)

Key Differences in Pediatric vs. Adult Tuberculosis:

- Children typically have paucibacillary disease (fewer bacteria), making diagnosis more challenging

- Rapid progression from infection to disease is more common in children

- Extrapulmonary manifestations are more frequent in children

- Cavitary disease is less common in young children but becomes more prevalent in adolescents

- Children under 10 years rarely transmit the disease to others

4. Clinical Manifestations

The clinical presentation of tuberculosis in children varies widely depending on the site of disease, age of the child, and immune status. Recognizing these manifestations is a crucial nursing skill for early identification and prompt management.

4.1 Pulmonary Tuberculosis

Pulmonary tuberculosis is the most common form in children. However, unlike in adults, children often present with non-specific symptoms that can mimic other common childhood respiratory infections.

Common Symptoms of Pulmonary TB in Children:

- Persistent, non-remitting cough (>2 weeks)

- Low-grade fever, especially in the afternoon

- Night sweats

- Unexplained weight loss or failure to thrive

- Decreased activity or playfulness

- Fatigue and malaise

- Poor appetite

Clinical Pearl:

Young children often do not produce sputum and may demonstrate “silent pneumonia” with minimal respiratory symptoms despite significant disease on chest imaging.

4.2 Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis

Extrapulmonary TB is more common in children than adults, occurring in about 30-40% of pediatric TB cases. The manifestations depend on the site of involvement.

| Extrapulmonary Site | Clinical Manifestations | Nursing Assessment Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Lymph Node TB (Scrofula) | Painless, firm, non-tender cervical lymphadenopathy; may develop fistulae | Palpable lymph nodes, often matted together; possible skin changes |

| TB Meningitis | Gradual onset of headache, irritability, vomiting, fever, altered consciousness | Subtle neurological signs, neck stiffness, cranial nerve palsies (late) |

| Miliary TB | Acute or insidious onset fever, weight loss, respiratory distress | Hepatosplenomegaly, generalized lymphadenopathy, respiratory findings |

| Skeletal TB | Pain and swelling of affected bone/joint, limited movement | Most commonly affects spine (Pott’s disease); gibbus deformity may be present |

| Abdominal TB | Abdominal pain, distension, diarrhea, or constipation | Ascites, abdominal masses, hepatosplenomegaly |

Mnemonic: “CHILDREN with TB”

To remember common clinical manifestations in pediatric tuberculosis:

- C – Cough (persistent > 2 weeks)

- H – Hepatosplenomegaly (in disseminated TB)

- I – Irritability and behavior changes

- L – Lymphadenopathy (especially cervical)

- D – Decreased appetite and weight loss

- R – Respiratory distress (in severe cases)

- E – Evening low-grade fever

- N – Night sweats

- T – Tiredness/fatigue

- B – Bacilli (often paucibacillary in children)

5. Diagnosis and Identification

Diagnosing tuberculosis in children is challenging due to non-specific symptoms, paucibacillary disease, and difficulties in obtaining appropriate specimens. A comprehensive approach that combines clinical assessment, history of exposure, and diagnostic tests is essential.

5.1 History and Physical Examination

Key Components of History Taking:

- Contact history: Close contact with a person with infectious TB (especially household contacts)

- Symptom duration: Persistent symptoms not responding to standard treatments

- Growth patterns: Review of growth chart to identify failure to thrive or weight loss

- Prior TB testing or treatment: Previous tuberculin skin tests or TB medications

- Risk factors: HIV status, immunosuppression, malnutrition, recent immigration from TB-endemic areas

Physical Examination Findings:

- General: Growth assessment, vital signs (including pattern of fever)

- Respiratory: Abnormal breath sounds, decreased air entry, dullness to percussion

- Lymphatic: Enlarged lymph nodes, especially cervical, axillary, or supraclavicular

- Neurological: Signs of meningeal irritation, altered mental status

- Musculoskeletal: Joint swelling, limited mobility, spinal deformity

- Abdominal: Hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, abdominal masses

5.2 Diagnostic Tests

Bacteriological Confirmation:

Though challenging in children, bacteriological confirmation should be attempted whenever possible:

- Specimen collection: Sputum (induced or expectorated), gastric aspirates, nasopharyngeal aspirates, bronchoalveolar lavage, or specimens from extrapulmonary sites

- Microscopy: Acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear – often negative in children due to paucibacillary disease

- Culture: Gold standard but takes 2-8 weeks; more sensitive than microscopy

- Molecular testing: Xpert MTB/RIF assay – rapid molecular test that can detect TB and rifampicin resistance within hours

Immunological Tests:

- Tuberculin Skin Test (TST): Measures delayed-type hypersensitivity response to TB antigens

- Positive in immunocompetent children: ≥10mm induration

- Positive in immunocompromised or severely malnourished children: ≥5mm induration

- Interferon-Gamma Release Assays (IGRAs): Blood tests that measure T-cell response to TB-specific antigens

- Not recommended as a replacement for TST in low-resource settings

- May be used as an adjunct to TST in certain situations

Radiological Studies:

- Chest X-ray: Essential tool for diagnosing pulmonary TB in children

- Common findings: Hilar lymphadenopathy, segmental/lobar consolidation, miliary pattern, cavities (in adolescents)

- Other imaging: CT scan, MRI, or ultrasound may be needed for extrapulmonary TB

Important Consideration:

A negative test (TST, IGRA, or even bacteriological tests) does not rule out TB in children. Diagnosis should be based on a comprehensive assessment including history, clinical findings, and appropriate investigations.

Diagnostic Approach:

The WHO recommends a systematic approach to TB diagnosis in children that includes:

- Careful history (including TB contact and symptoms)

- Clinical examination (including growth assessment)

- Tuberculin skin testing (where available)

- Bacteriological confirmation whenever possible

- Relevant investigations for suspected pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB

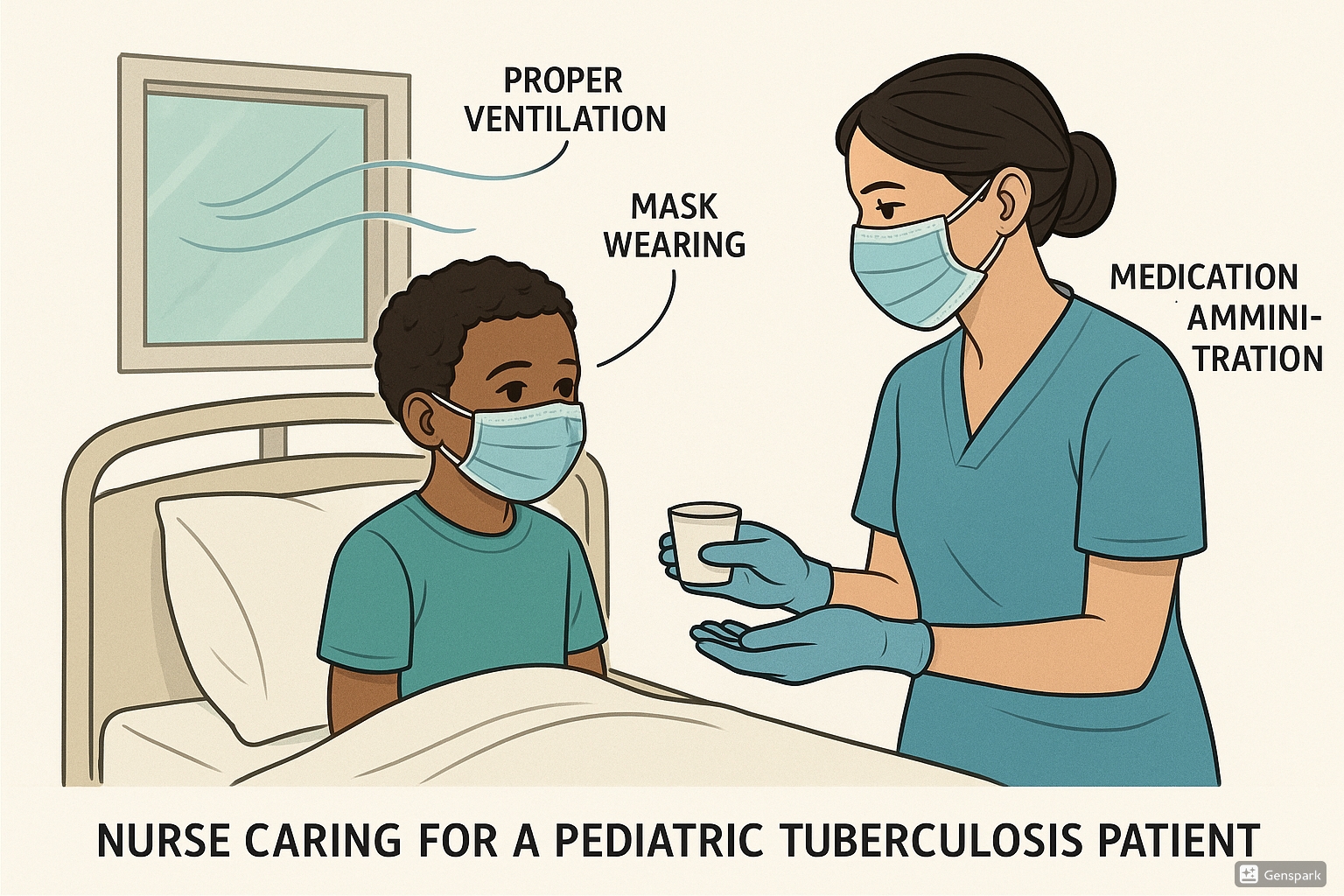

6. Nursing Management in Hospital Setting

Nurses play a pivotal role in the care of children with tuberculosis in hospital settings. A comprehensive nursing care plan addresses both the physiological and psychosocial needs of the child and family.

6.1 Assessment

Initial Nursing Assessment:

- Respiratory assessment: Rate, depth, pattern, use of accessory muscles, oxygen saturation, presence of cough

- Nutritional assessment: Weight, height, BMI, dietary intake, presence of anorexia

- Hydration status: Mucous membranes, skin turgor, urine output

- Activity tolerance: Energy level, fatigue, ability to perform age-appropriate activities

- Pain assessment: Location, severity, characteristics (especially relevant for extrapulmonary TB)

- Psychosocial assessment: Understanding of disease, coping mechanisms, family support

Ongoing Monitoring:

- Vital signs, especially temperature patterns and respiratory parameters

- Weight gain/loss trends

- Medication side effects

- Response to treatment

- Symptoms progression or resolution

6.2 Nursing Diagnosis

Common nursing diagnoses for children with tuberculosis include:

| Nursing Diagnosis | Related Factors | Defining Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Ineffective Breathing Pattern | Pulmonary infiltrates, pleural effusion, respiratory muscle fatigue | Dyspnea, tachypnea, abnormal breath sounds, altered chest excursion |

| Imbalanced Nutrition: Less than Body Requirements | Increased metabolic demands, anorexia, nausea | Weight loss, poor appetite, decreased energy, altered growth patterns |

| Activity Intolerance | Fatigue, weakness, poor oxygenation | Decreased ability to play or participate in age-appropriate activities |

| Risk for Infection Transmission | Presence of active TB, airborne transmission route | Potential for spreading TB bacteria to others |

| Deficient Knowledge | Unfamiliarity with disease process, treatment regimen | Questions about disease, inaccurate follow-through of instructions |

| Interrupted Family Processes | Hospitalization, chronic illness, stigma | Changes in family routines, communication patterns, role responsibilities |

6.3 Planning and Interventions

Nursing Care Plan for Pediatric Tuberculosis

For Ineffective Breathing Pattern:

- Position child to maximize chest expansion (semi-Fowler’s or as tolerated)

- Monitor respiratory rate, depth, and pattern every 4 hours or as indicated

- Administer oxygen therapy as prescribed

- Assess for signs of respiratory distress and intervene promptly

- Assist with deep breathing exercises appropriate for age

- Document and report changes in respiratory status

For Imbalanced Nutrition:

- Monitor daily weights and document on growth chart

- Provide small, frequent, nutrient-dense meals

- Offer child’s preferred foods within dietary guidelines

- Administer antiemetics before meals if nausea is present

- Involve dietitian for individualized nutritional plan

- Consider nutritional supplements if needed

- Document intake and output accurately

For Risk for Infection Transmission:

- Implement airborne precautions as per facility protocol

- Ensure proper ventilation of patient’s room (negative pressure if available)

- Teach and reinforce respiratory hygiene (covering mouth when coughing)

- Limit visitors according to facility policy

- Use appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE)

- Educate family about infection control measures

For Medication Management:

- Administer anti-TB medications as prescribed, following correct timing

- Monitor for adverse drug reactions and report promptly

- Ensure medications are taken with appropriate foods or on empty stomach as indicated

- Document medication administration and child’s response

- Educate child and family about importance of medication adherence

- Implement strategies to improve palatability of medications for children

For Psychosocial Support:

- Provide age-appropriate explanation of disease and treatments

- Allow expression of fears and concerns

- Facilitate continued education during hospitalization

- Encourage family involvement in care

- Address stigma associated with tuberculosis

- Connect family with social services and support groups as needed

Medication Administration:

The standard treatment for drug-susceptible TB in children follows the “RIPE” regimen:

- R – Rifampin (10-20 mg/kg/day)

- I – Isoniazid (10-15 mg/kg/day)

- P – Pyrazinamide (30-40 mg/kg/day)

- E – Ethambutol (15-25 mg/kg/day)

Initial phase (first 2 months): All four drugs

Continuation phase (4 months): Rifampin and Isoniazid

6.4 Evaluation

Ongoing evaluation of nursing interventions is essential to determine effectiveness and make necessary adjustments to the care plan.

Expected Outcomes:

- Improved respiratory function with normalized respiratory rate and pattern

- Weight gain and improved nutritional status

- Increased activity tolerance and energy levels

- Absence of medication side effects

- Demonstrated understanding of disease process and management by child and family

- Adherence to treatment regimen

- No evidence of TB transmission to others

Documentation:

Thorough documentation is crucial and should include:

- Detailed assessments and findings

- Interventions implemented and child’s response

- Medication administration and any adverse effects

- Progress toward goals

- Education provided to child and family

- Plan for ongoing care and discharge

7. Nursing Management in Home Setting

Most children with tuberculosis can be managed at home after initial diagnosis and stabilization. Effective home care requires comprehensive education, monitoring, and support systems.

7.1 Home Care Instructions

Environmental Modifications:

- Ensure adequate ventilation in the home

- Maximize natural light (UV light kills TB bacteria)

- Minimize exposure to respiratory irritants (smoke, dust)

- Maintain clean living conditions

Infection Control at Home:

- For infectious TB cases:

- Isolate child in a well-ventilated room if possible

- Teach proper cough etiquette

- Limit close contact with others until non-infectious

- Consider mask-wearing if appropriate

- Note: Most young children with TB are not highly infectious to others

Nutrition and Hydration:

- Provide nutrient-rich diet with adequate protein, calories, and micronutrients

- Encourage adequate fluid intake

- Monitor weight weekly

- Consider nutritional supplements if recommended

Rest and Activity:

- Balance rest periods with gradual increase in activity as tolerated

- Return to school based on healthcare provider’s recommendation (usually after becoming non-infectious)

- Gradually resume normal activities as symptoms improve

7.2 Medication Adherence

Adherence to the full course of TB treatment is essential to prevent treatment failure, relapse, and development of drug resistance.

Strategies to Promote Adherence:

- Directly Observed Therapy (DOT): Having a healthcare worker, community health worker, or trained family member directly observe the child taking each dose of medication

- Fixed-dose combinations: Simplifying regimens with combination pills when appropriate

- Medication calendar: Visual reminder system for daily medication

- Alarms or reminders: Setting phone alarms or other reminders

- Integrate into daily routine: Linking medication administration with established routines

- Child-friendly formulations: Using dispersible tablets or other palatable formulations

Mnemonic: “ADHERE”

To remember key strategies for medication adherence in pediatric TB:

- A – Anticipate side effects and manage them promptly

- D – Directly observe therapy when possible

- H – Home visits by healthcare workers for support

- E – Educate child and family about importance of completing treatment

- R – Regular follow-up appointments to monitor progress

- E – Engage the whole family in the treatment plan

7.3 Monitoring and Follow-up

Regular Assessment:

- Monitor for treatment response (symptom improvement, weight gain)

- Assess for medication side effects

- Monitor growth and development

- Follow-up chest X-rays as recommended

- Laboratory monitoring as indicated (liver function tests with certain medications)

Common Side Effects to Monitor:

| Medication | Common Side Effects | Nursing Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Isoniazid | Peripheral neuropathy, hepatitis, rash | Monitor for numbness/tingling; may administer pyridoxine (vitamin B6) to prevent neuropathy |

| Rifampin | Orange-colored body fluids, hepatitis, flu-like symptoms, GI upset | Warn about harmless orange discoloration of urine, tears, saliva; give on empty stomach if possible |

| Pyrazinamide | Hepatotoxicity, arthralgia, rash, GI upset | Monitor for joint pain; assess liver function periodically |

| Ethambutol | Optic neuritis (rare in children at recommended doses) | Monitor visual acuity and color discrimination in older children who can cooperate |

Red Flags Requiring Immediate Attention:

- Jaundice or dark urine (signs of hepatotoxicity)

- Severe rash or itching (hypersensitivity reaction)

- Visual changes (with ethambutol)

- Persistent vomiting or inability to take medications

- Worsening symptoms despite treatment

- Development of new neurological symptoms

Important Warning:

Premature discontinuation of TB treatment can lead to treatment failure, relapse, and development of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Always emphasize the importance of completing the full treatment course even if symptoms improve.

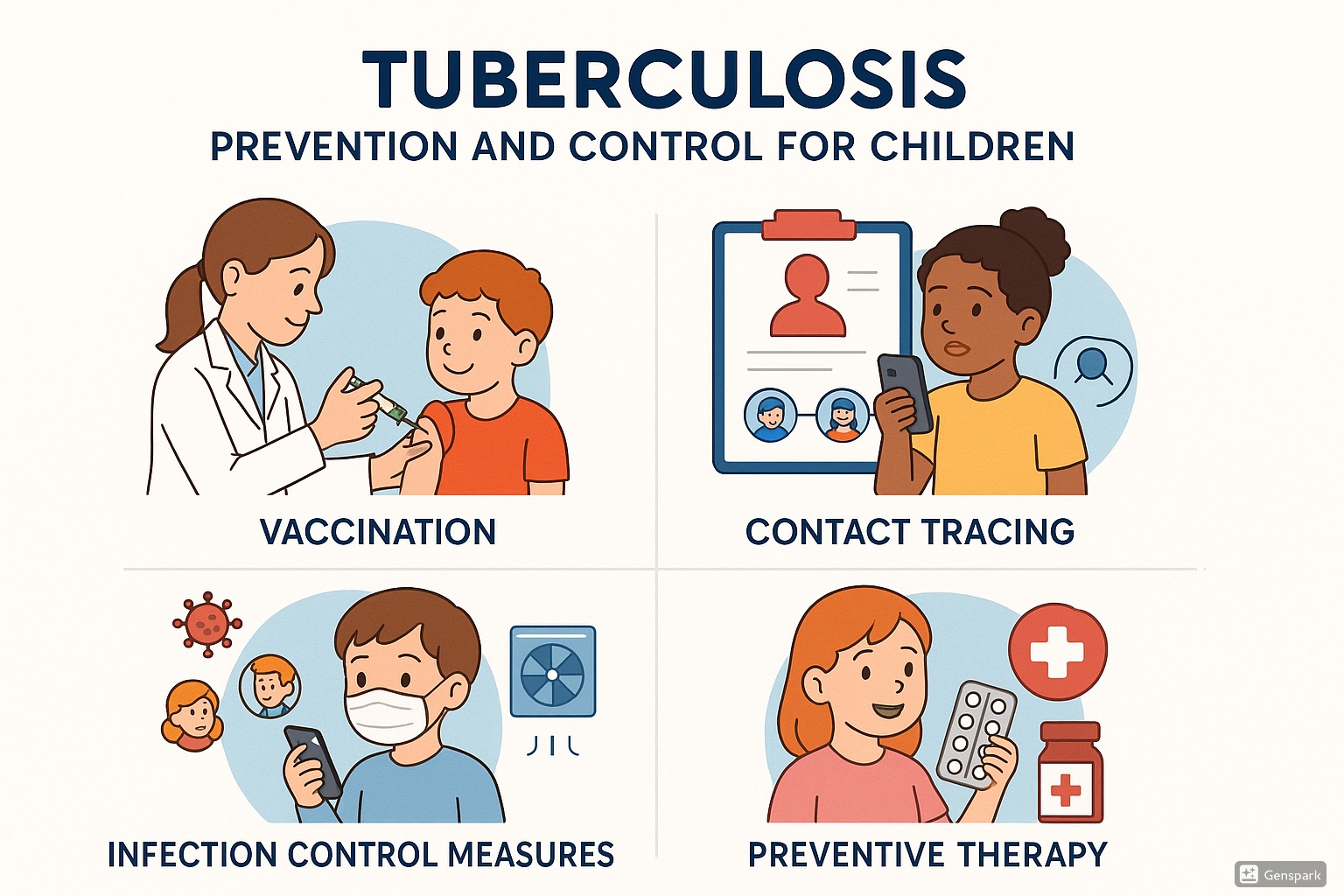

8. Prevention and Control Measures

Prevention and control of tuberculosis in children involve multiple strategies at individual, family, and community levels.

8.1 BCG Vaccination

Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is a live attenuated vaccine derived from Mycobacterium bovis that provides protection against severe forms of TB in children.

Key Points About BCG Vaccination:

- Efficacy: Most effective against severe forms like TB meningitis and miliary TB (70-80% protection)

- Timing: Typically administered at birth or early infancy in TB-endemic countries

- Administration: Intradermal injection in the upper arm

- Normal reaction: Small papule → ulcer → healing with small scar

- Contraindications:

- Known HIV infection

- Immunodeficiency disorders

- Severe malnutrition

Nursing Consideration:

In areas with high HIV prevalence, WHO recommends that infants who are known to be HIV-infected should not receive BCG vaccination. However, if HIV status is unknown in an infant born to an HIV-positive mother, BCG should be given according to local vaccination policies if the infant appears healthy.

8.2 Contact Tracing

Contact tracing is a crucial strategy for early identification of TB cases and prevention of further transmission.

Contact Screening Process:

- Identify contacts: All household members and close contacts of infectious TB cases

- Prioritize high-risk contacts:

- Children under 5 years of age

- HIV-infected individuals

- Those with symptoms suggestive of TB

- Screen for symptoms: Persistent cough, fever, weight loss, decreased activity

- Perform diagnostic tests: TST/IGRA, chest X-ray, other tests as indicated

- Classify contacts: TB disease, TB infection, or no TB

- Provide appropriate management:

- TB disease: Full treatment

- TB infection: Preventive therapy

- No TB: Education and follow-up as needed

Isoniazid Preventive Therapy (IPT):

- Indication: Child contacts <5 years without TB disease, HIV-infected contacts of any age

- Dosage: Isoniazid 10 mg/kg (range 7-15 mg/kg) daily for 6 months

- Efficacy: Reduces risk of developing TB disease by 60-90%

- Monitoring: Monthly assessment for adherence, side effects, and symptom development

8.3 Infection Control

Infection control measures are essential to prevent TB transmission, especially in healthcare settings and households.

Administrative Controls:

- Early identification and isolation of infectious TB cases

- Prompt initiation of effective treatment

- Education of patients, families, and healthcare workers

- Implementation of TB infection control policies and procedures

Environmental Controls:

- Adequate ventilation (natural or mechanical)

- Directional airflow (from clean to less clean areas)

- HEPA filtration or ultraviolet germicidal irradiation in high-risk areas

- Negative pressure isolation rooms for infectious cases

Personal Protective Equipment:

- N95 respirators for healthcare workers caring for infectious TB patients

- Surgical masks for patients with infectious TB when outside isolation rooms

Special Considerations for Pediatric Settings:

- Separation of suspected TB cases from immunocompromised children

- Screening of adults accompanying children for TB symptoms

- Age-appropriate education about respiratory hygiene

- Fast-tracking of children with TB symptoms to minimize time in waiting areas

9. Special Considerations

9.1 HIV Co-infection

TB/HIV co-infection presents unique challenges in diagnosis and management, particularly in children.

Challenges in TB/HIV Co-infection:

- Increased risk of rapid progression from infection to disease

- Atypical clinical presentations

- More frequent extrapulmonary manifestations

- Lower sensitivity of diagnostic tests (TST, AFB smear)

- Increased risk of adverse drug reactions

- Complex drug interactions between anti-TB and antiretroviral medications

Management Principles:

- HIV testing: All children with suspected or confirmed TB should be tested for HIV

- TB treatment: Same regimens as HIV-negative children, but closer monitoring required

- ART timing: Initiate ART as soon as TB treatment is tolerated (within 2-8 weeks)

- Monitoring: Regular assessment for drug interactions, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), and treatment response

- Nutritional support: Enhanced nutritional support due to increased metabolic demands

- Preventive therapy: All HIV-infected children exposed to TB should receive preventive therapy after TB disease is excluded

Important Consideration:

BCG vaccination is contraindicated in children with known HIV infection due to the risk of disseminated BCG disease. HIV-exposed infants should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis according to local guidelines.

9.2 Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis

Drug-resistant TB (DR-TB) in children requires specialized management approaches, including modified treatment regimens and enhanced monitoring.

Types of Drug Resistance:

- Mono-resistance: Resistance to one first-line anti-TB drug

- Multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB): Resistance to at least isoniazid and rifampicin

- Extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB): MDR-TB plus resistance to a fluoroquinolone and at least one second-line injectable agent

Suspecting DR-TB in Children:

- Contact with a known DR-TB case

- Treatment failure despite good adherence

- Recurrence of TB after completing treatment

- Exposure to an adult with treatment failure or who has been previously treated

- From a high DR-TB prevalence area

Management Principles:

- Diagnosis: Bacteriological confirmation and drug susceptibility testing whenever possible

- Treatment: Individualized regimens based on drug susceptibility pattern of the child or source case

- Duration: Usually longer than drug-susceptible TB (18-24 months)

- Monitoring: More frequent clinical, radiological, and laboratory monitoring

- Support: Enhanced adherence support and management of adverse effects

- Contact management: Careful evaluation of all contacts of DR-TB cases

Nursing Role:

Nurses play a critical role in DR-TB management through medication administration, monitoring for adverse effects, providing emotional support, and ensuring adherence to the complex and lengthy treatment regimens. Patient and family education about the importance of completing the full course of treatment is essential.

10. Case Study

Pediatric Tuberculosis: A Nursing Case Study

Patient Information:

Aisha, a 4-year-old female, is brought to the clinic by her mother with complaints of persistent cough for 3 weeks, low-grade fever in the evenings, decreased appetite, and weight loss. Her mother reports that Aisha has become less active and tires easily. The family recently moved in with Aisha’s uncle, who was diagnosed with pulmonary TB two months ago and is currently on treatment.

Assessment Findings:

- Vital signs: Temperature 38.2°C, respiratory rate 32/min, heart rate 110/min

- Weight: 14 kg (decreased from 15.5 kg three months ago)

- Physical examination: Thin appearance, mild respiratory distress, scattered crackles in the right upper lung field, palpable cervical lymph nodes

- TST: 14 mm induration at 48 hours

- Chest X-ray: Right hilar lymphadenopathy with right upper lobe infiltrate

- Gastric aspirate: AFB smear negative, GeneXpert MTB/RIF positive (rifampicin-sensitive)

- HIV test: Negative

Nursing Diagnoses:

- Ineffective Breathing Pattern related to pulmonary infection

- Imbalanced Nutrition: Less than Body Requirements related to anorexia and increased metabolic demands

- Activity Intolerance related to fatigue and respiratory compromise

- Risk for Infection Transmission related to active pulmonary TB

- Deficient Knowledge (family) related to unfamiliarity with tuberculosis management

Nursing Interventions:

- For Ineffective Breathing Pattern:

- Assess respiratory status every 4 hours

- Position in semi-Fowler’s position to optimize breathing

- Administer oxygen if needed to maintain saturation >95%

- Teach deep breathing exercises appropriate for age

- For Imbalanced Nutrition:

- Monitor daily weight

- Provide small, frequent, high-calorie meals

- Offer favorite foods within dietary guidelines

- Consult with dietitian for nutritional supplements

- For Risk for Infection Transmission:

- Isolate until determined to be non-infectious

- Teach proper cough etiquette

- Ensure adequate ventilation

- Screen all household contacts for TB

- For Medication Management:

- Administer anti-TB medications as prescribed: Isoniazid, Rifampin, Pyrazinamide, and Ethambutol for 2 months, followed by Isoniazid and Rifampin for 4 months

- Monitor for adverse effects: Liver function tests at baseline and monthly

- Implement strategies to improve medication palatability

- Educate family on importance of adherence

- For Family Education:

- Explain disease process, transmission, and treatment plan

- Demonstrate medication administration techniques

- Teach signs of adverse effects to report

- Discuss infection control measures at home

- Provide information on follow-up appointments

Outcomes:

After two weeks of treatment, Aisha’s fever resolves, and her appetite improves. She is discharged home with directly observed therapy arranged through the local health department. At the 2-month follow-up, her weight has increased to 15 kg, her cough has resolved, and her chest X-ray shows improvement. All household contacts have been screened, and Aisha’s 2-year-old sibling is placed on isoniazid preventive therapy. The family demonstrates good understanding of the treatment plan and infection control measures.

11. References

- World Health Organization. (2022). Guidance for national tuberculosis programmes on the management of tuberculosis in children and adolescents (2nd ed.).

- Cruz, A. T., & Starke, J. R. (2019). Pediatric tuberculosis. Pediatrics in Review, 40(4), 168-178.

- Marais, B. J., & Schaaf, H. S. (2014). Childhood tuberculosis: an emerging and previously neglected problem. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America, 28(4), 727-749.

- World Health Organization. (2018). Roadmap towards ending TB in children and adolescents (2nd ed.).

- Perez-Velez, C. M., & Marais, B. J. (2012). Tuberculosis in children. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(4), 348-361.

- Schaaf, H. S., Marais, B. J., Whitelaw, A., Hesseling, A. C., Eley, B., Hussey, G. D., & Donald, P. R. (2007). Culture-confirmed childhood tuberculosis in Cape Town, South Africa: a review of 596 cases. BMC Infectious Diseases, 7(1), 140.

- Hatherill, M., Verver, S., & Mahomed, H. (2012). Consensus statement on diagnostic end points for infant tuberculosis vaccine trials. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 54(4), 493-501.

- World Health Organization. (2016). WHO treatment guidelines for drug-resistant tuberculosis: 2016 update.

- Getahun, H., Sculier, D., Sismanidis, C., Grzemska, M., & Raviglione, M. (2012). Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of tuberculosis in children and mothers: evidence for action for maternal, neonatal, and child health services. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 205(suppl_2), S216-S227.

- Shingadia, D., & Novelli, V. (2003). Diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in children. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 3(10), 624-632.