Preterm Labor: Prevention and Management

Comprehensive nursing guide on assessment, prevention, and evidence-based interventions

Table of Contents

1. Introduction to Preterm Labor

1.1. Definition and Significance

Preterm labor is defined as regular contractions leading to cervical changes between 20 weeks and 37 weeks of gestation. This critical obstetric complication demands prompt recognition and intervention to improve maternal and neonatal outcomes.

The significance of preterm labor lies in its substantial contribution to neonatal morbidity and mortality worldwide. Approximately 15 million babies are born preterm each year, making it a leading cause of death in children under five years of age. The prevention and management of preterm labor represent significant challenges in maternal-fetal medicine and nursing practice.

1.2. Epidemiology and Global Impact

Preterm birth rates vary significantly worldwide, with rates ranging from 5% to 18% across different regions:

- Globally, approximately 11% of all live births are preterm

- In low-income countries, the rate can exceed 15% of births

- In high-income countries, rates generally range from 5-9%

- The United States has a preterm birth rate of approximately 10%

The socioeconomic impact of preterm birth is substantial, encompassing immediate healthcare costs of neonatal intensive care and long-term expenses related to ongoing health issues, developmental support, and special education services. For healthcare systems worldwide, the management of preterm labor represents a significant allocation of resources.

2. Pathophysiology of Preterm Labor

2.1. Underlying Mechanisms

The pathophysiology of preterm labor is complex and multifactorial. Four primary pathways have been identified that can lead to preterm labor:

1. Inflammation and Infection

Microbial invasion or inflammation triggers cytokine production, leading to prostaglandin release and matrix metalloproteinase activation, which results in cervical remodeling and uterine contractions.

2. Uteroplacental Ischemia/Hemorrhage

Inadequate blood flow or placental bleeding activates the maternal-fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, promoting uterine contractility and cervical changes.

3. Uterine Overdistention

Excessive stretching of the myometrium (due to multiple gestation or polyhydramnios) increases expression of contraction-associated proteins and gap junctions, facilitating coordinated contractions.

4. Premature Activation of the Maternal-Fetal HPA Axis

Maternal or fetal stress leads to increased corticotropin-releasing hormone production, altering the progesterone/estrogen ratio and promoting labor.

Mnemonic: “PIPE” Pathways to Preterm Labor

- P – Placental ischemia/hemorrhage

- I – Inflammation and infection

- P – Premature activation of maternal-fetal HPA axis

- E – Excessive uterine stretch

2.2. Cervical Changes

Cervical remodeling is a crucial component of the preterm labor process, involving several physiological changes:

| Phase | Changes | Biochemical Markers |

|---|---|---|

| Softening | Increased tissue compliance without structural changes | ↑ Hyaluronic acid, ↓ Collagen cross-linking |

| Ripening | Collagen reorganization and increased water content | ↑ Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), ↓ Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) |

| Dilation | Opening of the cervical os | ↑ Interleukin-8, ↑ Prostaglandins |

| Effacement | Shortening and thinning of the cervix | ↑ Inflammatory cytokines, ↑ Neutrophil infiltration |

Cervical changes in preterm labor often occur prematurely due to pathological processes rather than the normal physiological processes seen at term. These changes can sometimes be detected through transvaginal ultrasound measurement of cervical length, which serves as an important predictor of preterm birth risk.

2.3. Uterine Activity

Myometrial contractions in preterm labor involve intricate cellular mechanisms:

- Increased calcium influx into myometrial cells

- Enhanced expression of oxytocin receptors

- Formation of gap junctions between myometrial cells

- Upregulation of prostaglandin receptors

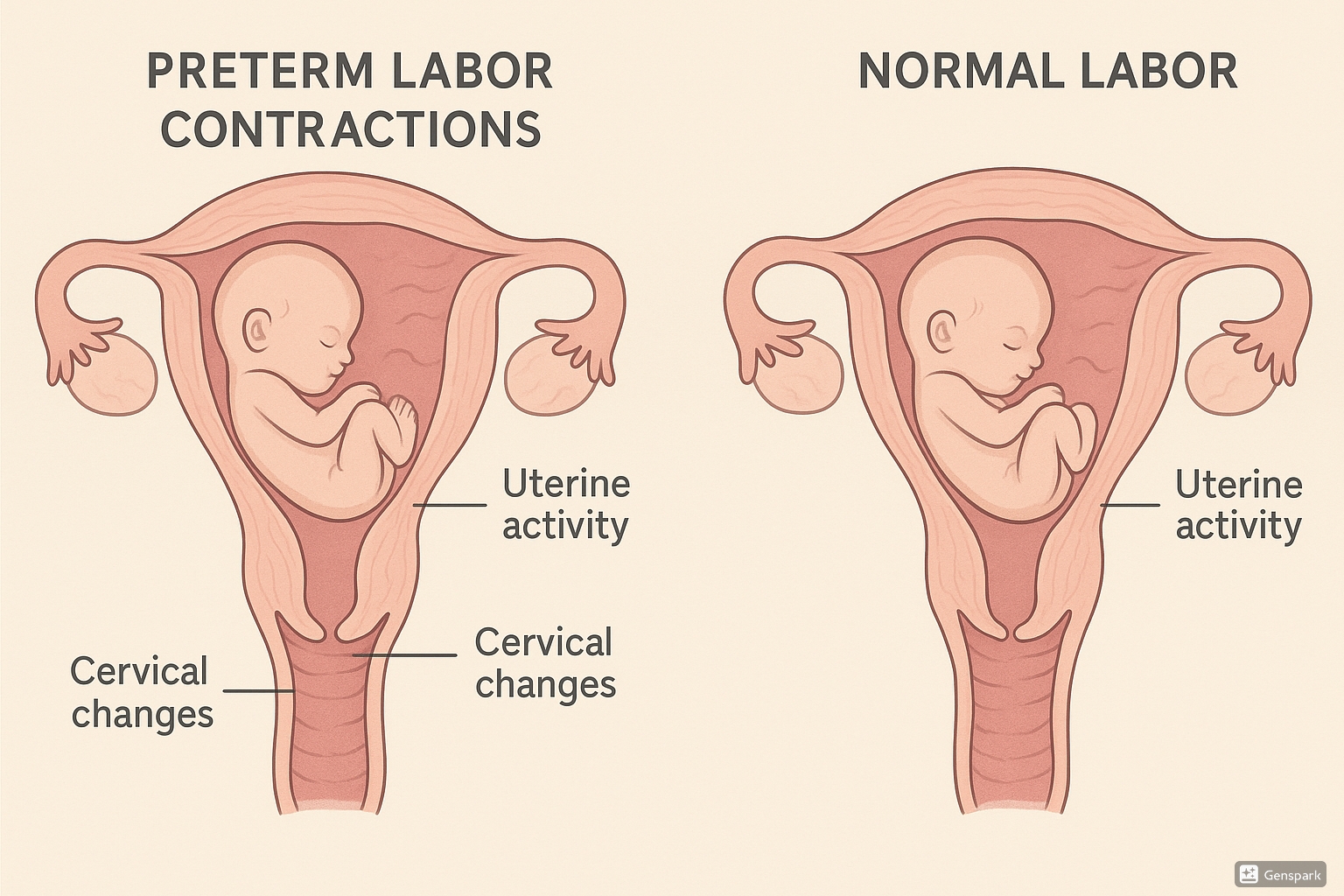

Physiological comparison between preterm and normal labor showing cervical changes and uterine activity patterns

Unlike normal labor at term, preterm uterine activity often displays irregular patterns and may initially be less intense, making early recognition challenging. This highlights the importance of monitoring subtle changes in patients with risk factors for preterm labor.

3. Risk Factors and Assessment

3.1. Maternal Risk Factors

Multiple maternal characteristics and conditions increase the risk for preterm labor:

| Category | Risk Factors | Relative Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic |

|

1.2-2.5 |

| Behavioral |

|

1.5-3.0 |

| Medical Conditions |

|

2.0-4.0 |

| Psychological |

|

1.5-2.0 |

Mnemonic: “PRETERM” Maternal Risk Factors

- P – Previous preterm birth

- R – Race (African American)

- E – Extremes of age (<18 or >35)

- T – Tobacco and substance use

- E – Economic disadvantage

- R – Reproductive abnormalities

- M – Medical conditions

3.2. Obstetric Risk Factors

Previous pregnancy outcomes and current obstetric factors significantly influence preterm labor risk:

History-Related Factors

- Previous preterm birth (strongest predictor)

- Prior pregnancy loss after 16 weeks

- History of cervical procedures (LEEP, cone biopsy)

- Uterine anomalies or fibroids

- Previous cesarean delivery

Current Pregnancy Factors

- Multiple gestation

- Polyhydramnios

- Vaginal bleeding

- Shortened cervical length (<25 mm)

- Placenta previa or abruption

- Genital tract infections

High-Risk Alert

A history of spontaneous preterm birth is the single strongest predictor of recurrent preterm birth, with a 2-6 fold increased risk. This risk escalates with each additional preterm birth and decreases with each term delivery.

3.3. Risk Assessment Tools

Several clinical tools can help identify women at increased risk for preterm labor:

| Assessment Tool | Description | Clinical Utility | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical Length Measurement | Transvaginal ultrasound to measure cervical length; <25 mm indicates increased risk | High predictive value for women with symptoms | High |

| Fetal Fibronectin (fFN) | Detection of fFN in cervicovaginal fluid between 22-34 weeks | High negative predictive value (>99%) | High |

| Phosphorylated Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein-1 (phIGFBP-1) | Detection in cervical secretions indicates decidual disruption | Moderate predictive value | Moderate |

| Placental Alpha Macroglobulin-1 (PAMG-1) | Detection in vaginal fluid indicates membrane rupture or imminent labor | High specificity for preterm labor | Moderate |

| Combined Risk Scoring Systems | Integration of multiple risk factors into predictive models | Improved risk stratification | Moderate |

Clinical Pearl

The combination of cervical length measurement and fetal fibronectin testing provides the highest predictive accuracy for preterm birth in symptomatic women. A negative fFN test in a woman with symptoms has a >99% negative predictive value for delivery within the next 7-14 days.

4. Prevention Strategies

4.1. Primary Prevention

Primary prevention strategies aim to prevent preterm labor before it begins, targeting all pregnant women or those with identified risk factors:

Preconception Care

- Optimization of maternal health conditions

- Nutritional counseling and supplementation

- Substance use cessation programs

- Inter-pregnancy spacing (18-24 months optimal)

- Reproductive life planning

Prenatal Care

- Early and consistent prenatal visits

- Screening and treatment for infections

- Nutritional supplementation (iron, folate)

- Risk factor modification

- Patient education on warning signs

- Smoking cessation interventions

Evidence Highlight

A systematic review of 15 randomized controlled trials demonstrated that smoking cessation interventions during pregnancy reduce the risk of preterm birth by approximately 14% (RR 0.86; 95% CI 0.74-0.98) while also decreasing the incidence of low birth weight and increasing mean birth weight.

Source: Chamberlain C, et al. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2:CD001055.

4.2. Secondary Prevention

Secondary prevention targets women with identified risk factors for preterm birth, employing interventions to prevent preterm labor onset:

| Intervention | Target Population | Effectiveness | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone Supplementation | Women with history of spontaneous preterm birth or short cervix | Reduces preterm birth risk by 30-45% | High |

| Cervical Cerclage | Women with short cervix (<25 mm) and history of preterm birth | Reduces preterm birth risk by 30% | High |

| Cervical Pessary | Women with short cervix without prior preterm birth | Mixed results; may be beneficial in select populations | Moderate |

| Low-dose Aspirin | Women at risk for preeclampsia | Reduces preterm birth risk secondary to preeclampsia | Moderate |

| Antibiotic Treatment | Women with bacterial vaginosis or asymptomatic bacteriuria | Reduces preterm birth associated with infection | Moderate |

Clinical Pearl: Progesterone Administration

17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P): 250 mg intramuscularly weekly from 16-36 weeks for women with prior spontaneous preterm birth.

Vaginal progesterone: 90-200 mg daily from diagnosis of short cervix until 36 weeks.

4.3. Tertiary Prevention

Tertiary prevention focuses on interventions to improve outcomes once preterm labor has begun:

- Antenatal corticosteroids: Administration to accelerate fetal lung maturity

- Tocolytic therapy: Short-term delay of delivery to allow for other interventions

- Magnesium sulfate: Neuroprotection for the preterm infant

- Group B streptococcal prophylaxis: Prevention of early-onset neonatal infection

- Transfer to higher-level facility: Ensuring appropriate level of care for preterm infant

Critical Timing

Tertiary interventions are time-sensitive and most effective when implemented promptly after diagnosis of preterm labor. The therapeutic window for antenatal corticosteroids is optimal when administration occurs at least 24 hours before delivery but within 7 days of administration.

5. Management of Preterm Labor

5.1. Diagnosis and Assessment

Accurate diagnosis of preterm labor is crucial for initiating appropriate interventions:

Diagnostic Criteria for Preterm Labor: Regular uterine contractions (4 in 20 minutes or 8 in 60 minutes) accompanied by cervical change (dilation ≥2 cm or effacement ≥80%) in a woman between 20 and 37 weeks of gestation.

Initial Assessment Protocol

History and Risk Factor Assessment

Evaluate for risk factors, symptoms duration, maternal perception of fetal movement, and presence of vaginal discharge or bleeding.

Physical Examination

Vital signs, abdominal examination, sterile speculum examination (assess for amniotic fluid, obtain cultures), and digital cervical examination (if no contraindications).

Uterine Activity Monitoring

External tocodynamometry to assess contraction frequency, duration, and intensity.

Fetal Assessment

Fetal heart rate monitoring, ultrasound for position, estimated fetal weight, and amniotic fluid assessment.

Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

Complete blood count, urinalysis, cervicovaginal fFN (if 22-34 weeks), transvaginal ultrasound for cervical length, and other tests as indicated.

Nursing Tip: The TVCL-fFN Algorithm

For symptomatic women between 22-34 weeks:

- If cervical length >30 mm: low risk, consider discharge

- If cervical length <20 mm: high risk, initiate management

- If cervical length 20-30 mm: obtain fFN

- Negative fFN: low risk

- Positive fFN: increased risk, consider management

5.2. Tocolytic Therapy

Tocolytic medications inhibit uterine contractions, potentially delaying delivery to allow time for antenatal corticosteroid administration and maternal transfer if needed:

| Medication Class | Examples | Mechanism of Action | Dosing | Contraindications | Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium Channel Blockers | Nifedipine | Blocks calcium influx into myometrial cells | 20mg PO initially, then 10-20mg q4-6h | Hypotension, liver dysfunction | Hypotension, headache, flushing |

| Beta-adrenergic Agonists | Terbutaline | Stimulates β2 receptors, increasing cAMP | 0.25mg SC q3-4h | Cardiac disease, diabetes, hyperthyroidism | Tachycardia, pulmonary edema, hyperglycemia |

| COX Inhibitors | Indomethacin | Inhibits prostaglandin synthesis | 50-100mg loading dose, then 25-50mg q6h (max 48h) | >32 weeks gestation, renal dysfunction, platelet dysfunction | Premature ductus arteriosus closure, oligohydramnios |

| Oxytocin Antagonists | Atosiban | Competitive antagonism of oxytocin receptors | 6.75mg IV bolus, then 18mg/h for 3h, then 6mg/h | Liver/kidney impairment | Nausea, vomiting, headache |

| Magnesium Sulfate | – | Competes with calcium, decreases myometrial activity | 4-6g IV loading dose, then 1-4g/h maintenance | Myasthenia gravis, heart block, renal failure | Flushing, lethargy, respiratory depression, pulmonary edema |

Important Considerations

Tocolytics should be used cautiously and only for short-term therapy (24-48 hours) to allow for antenatal corticosteroid administration and maternal transfer if necessary. They have not been shown to improve neonatal outcomes beyond these temporary benefits.

Contraindications to tocolysis include:

- Severe preeclampsia or eclampsia

- Intrauterine infection

- Significant vaginal bleeding

- Fetal compromise necessitating delivery

- Maternal contraindications to specific agents

- Advanced cervical dilation (>4-5 cm)

Mnemonic: “STOP” – When NOT to Use Tocolytics

- S – Severe preeclampsia/eclampsia

- T – Term or near-term gestation (>34 weeks)

- O – Obvious infection or inflammation

- P – Placental problems (abruption, previa with bleeding)

5.3. Antimicrobial Therapy

Antimicrobial therapy in preterm labor management targets specific indications:

Group B Streptococcus Prophylaxis

Indicated for all women in preterm labor who:

- Have positive GBS culture results

- Have unknown GBS status and are <37 weeks

- Have unknown GBS status with PPROM

- Have unknown GBS status and will deliver imminently

- Have a history of GBS bacteriuria in current pregnancy

- Have previously delivered an infant with GBS disease

Regimen: Penicillin G 5 million units IV initial dose, then 2.5-3 million units IV q4h until delivery (or ampicillin as alternative)

Treatment of Intraamniotic Infection

Indicated when clinical chorioamnionitis is diagnosed, characterized by:

- Maternal fever (≥39.0°C or 38.0°C on two occasions)

- Maternal tachycardia

- Fetal tachycardia

- Uterine tenderness

- Foul-smelling amniotic fluid

- Elevated WBC count

Regimen: Ampicillin 2g IV q6h PLUS Gentamicin 1.5mg/kg IV q8h (with/without Clindamycin or Metronidazole) until delivery and maternal clinical improvement

Evidence Highlight

Routine antibiotic administration to women in preterm labor with intact membranes (without evidence of infection) is not recommended. Meta-analyses have shown no benefit in prolonging pregnancy or improving neonatal outcomes, and may potentially increase the risk of cerebral palsy.

Source: Flenady V, et al. Antibiotics for prelabour rupture of membranes at or near term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD001058.

6. Antenatal Corticosteroids

6.1. Mechanism of Action

Antenatal corticosteroids (ACS) accelerate fetal lung maturity and provide additional beneficial effects through multiple mechanisms:

Pulmonary Effects

- Increased surfactant production

- Enhanced structural maturation of alveoli

- Improved lung compliance

- Increased lung fluid clearance

- Reduced vascular permeability

Cardiovascular Effects

- Enhanced myocardial function

- Increased blood pressure regulation

- Improved cardiac output

- Enhanced response to catecholamines

Other Systemic Effects

- Decreased risk of IVH

- Maturation of GI enzymes

- Enhanced renal function

- Reduced inflammatory responses

- Decreased risk of NEC

At the cellular level, corticosteroids cross the placenta and bind to nuclear receptors in fetal cells, activating gene transcription for proteins involved in lung maturation, particularly surfactant production. The two key components of surfactant affected are phosphatidylcholine (lecithin) and phosphatidylglycerol, both crucial for reducing alveolar surface tension and preventing atelectasis.

Physiological Principle

Glucocorticoids accelerate fetal lung maturation by inducing type II pneumocytes to produce surfactant proteins A, B, and C, as well as increasing the activity of enzymes involved in phospholipid synthesis. This mimics the natural surge in fetal cortisol that occurs during late gestation to prepare for extrauterine life.

6.2. Administration Protocols

Evidence-based recommendations guide the administration of antenatal corticosteroids:

| Parameter | Recommendations | Evidence Grade |

|---|---|---|

| Gestational Age Window | Primary: 24 0/7 – 33 6/7 weeks Consider: 23 0/7 – 23 6/7 weeks Individualize: 34 0/7 – 36 6/7 weeks |

High |

| Medication Options | Betamethasone: 12 mg IM, 2 doses 24 hours apart Dexamethasone: 6 mg IM, 4 doses 12 hours apart |

High |

| Optimal Timing | Maximum benefit achieved when administered ≥24 hours and <7 days before delivery | High |

| Late Preterm ACS | Consider betamethasone for women 34 0/7-36 6/7 weeks at risk for preterm birth within 7 days and no prior ACS | Moderate |

| Rescue Course | Single repeat course if <34 weeks, initial course >14 days prior, and at risk for delivery within 7 days | Moderate |

| Multiple Gestation | Same regimen as singleton pregnancies | Moderate |

Administration Considerations

Antenatal corticosteroids should be administered to eligible patients regardless of:

- Race/ethnicity

- Anticipated availability of neonatal intensive care

- Status of fetal lung maturity testing

- Presence of preterm premature rupture of membranes (unless evidence of chorioamnionitis)

- Women with stable chronic medical conditions (including pregestational diabetes)

Nursing Protocol for ACS Administration

- Verify eligibility criteria and absence of contraindications

- Confirm gestational age through best available dating criteria

- Document time of first dose administration

- Schedule subsequent doses according to protocol

- Monitor maternal glucose levels in diabetic patients (may require insulin adjustment)

- Document completion of course or reason for incomplete administration

- Communicate ACS administration to all members of healthcare team

6.3. Benefits and Risks

Antenatal corticosteroids provide substantial benefits for preterm infants while carrying minimal risks:

Neonatal Benefits

- Reduction in respiratory distress syndrome (RR 0.66; 95% CI 0.56-0.77)

- Decreased neonatal mortality (RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.58-0.81)

- Reduction in intraventricular hemorrhage (RR 0.54; 95% CI 0.43-0.69)

- Decreased necrotizing enterocolitis (RR 0.50; 95% CI 0.32-0.78)

- Reduction in need for mechanical ventilation

- Decreased length of NICU stay

- Lower incidence of systemic infections in first 48 hours of life

Potential Concerns

- Transient maternal hyperglycemia

- Transient suppression of fetal heart rate variability

- Potential modest reduction in birthweight

- Theoretical concerns about neurodevelopmental effects with multiple courses (not substantiated in follow-up studies)

- Potential immune suppression if chorioamnionitis present

- Limited effectiveness if delivery occurs within 24 hours of first dose

Evidence Highlight: Number Needed to Treat

- To prevent one case of RDS: 11 infants

- To prevent one neonatal death: 22 infants

- To prevent one case of IVH: 18 infants

- To prevent one case of NEC: 50 infants

Source: Roberts D, et al. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3:CD004454.

The clear benefit-to-risk ratio strongly favors antenatal corticosteroid administration for eligible women. The World Health Organization and multiple professional organizations consider antenatal corticosteroids one of the most effective interventions available for improving outcomes in preterm infants.

7. Nursing Care and Considerations

Effective nursing care is central to the management of preterm labor, encompassing assessment, intervention, education, and emotional support:

| Nursing Function | Key Interventions and Considerations |

|---|---|

| Assessment and Monitoring |

|

| Medication Administration |

|

| Patient Education |

|

| Psychological Support |

|

| Coordination of Care |

|

Mnemonic: “PRETERM CARE” Nursing Priorities

- P – Provide emotional support to patient and family

- R – Recognize early signs of progressing labor

- E – Educate about medications and interventions

- T – Tocolytic administration and monitoring

- E – Evaluate fetal status continuously

- R – Report concerning findings promptly

- M – Monitor for infection and complications

- C – Corticosteroid administration according to protocol

- A – Assess maternal vital signs and contractions

- R – Reduce anxiety through information and support

- E – Ensure interdisciplinary communication and care coordination

Nursing Alert: Magnesium Sulfate Safety

When administering magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection or tocolysis:

- Ensure continuous maternal cardiac monitoring

- Check deep tendon reflexes and respiratory rate hourly

- Have calcium gluconate immediately available as an antidote

- Monitor urine output (should be >30 mL/hr)

- Check magnesium levels as ordered (therapeutic range: 4-8 mEq/L for tocolysis)

- Signs of toxicity: loss of deep tendon reflexes, respiratory depression, altered consciousness

Documentation Requirements

Ensure comprehensive documentation of all aspects of nursing care for patients with preterm labor, including:

- Timing of preterm labor diagnosis

- Interventions implemented and response

- Antenatal corticosteroid administration (timing of doses)

- Maternal assessment findings

- Fetal assessment data

- Patient education provided

- Healthcare team communications

Thorough documentation supports continuity of care, quality improvement, and may have medical-legal implications.

8. Global Best Practices

Preterm birth prevention and management strategies vary globally, with several innovative approaches demonstrating success:

The French Approach: Premature Labor Units

France has established specialized preterm labor units with standardized protocols focused on:

- Early identification and referral of at-risk women

- Intensive monitoring in specialized settings

- Limited interventions during labor and delivery

- Promotion of family-centered care

- Extensive postnatal follow-up programs

These practices have contributed to France having one of the lowest rates of very preterm birth morbidity in Europe.

The Swedish Model: Prevention Focus

Sweden’s comprehensive approach includes:

- Universal access to high-quality prenatal care

- Standardized risk assessment at first prenatal visit

- Early pregnancy ultrasound screening

- Centralized care for high-risk pregnancies

- Consistent application of evidence-based protocols

- Restrictive approach to multiple embryo transfer in fertility treatments

Sweden has achieved one of the lowest preterm birth rates worldwide at approximately 5.5%.

Kangaroo Mother Care: Low Resource Settings

Originally developed in Colombia, this approach includes:

- Skin-to-skin contact between mother and infant

- Exclusive breastfeeding when possible

- Early discharge with close follow-up

- Mother as primary provider of physical warmth and stimulation

Studies show KMC reduces mortality by 40% among preterm infants <2000g in low-resource settings and improves neurodevelopmental outcomes.

WHO Preterm Birth Action Plan

The World Health Organization’s framework emphasizes:

- Prevention through risk factor reduction

- Appropriate use of antenatal corticosteroids

- Tocolytic therapy for specific indications

- Magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection

- Delayed cord clamping

- Early initiation of continuous positive airway pressure

Implementation of these practices can reduce preterm mortality by up to 75% in low-resource settings.

Future Directions in Preterm Labor Management

- Predictive biomarkers: Development of serum, cervicovaginal, or salivary biomarkers for early prediction

- Cervical microbiome assessment: Characterization of healthy vs. pathological vaginal flora

- Transcriptomics and proteomics: Identifying molecular signatures that precede clinical symptoms

- Novel tocolytics: Oxytocin receptor antagonists and other targeted agents with improved side effect profiles

- Personalized risk assessment: Integration of clinical, biochemical, biophysical, and genetic markers

Research in these areas aims to move from reactive management to preventive strategies based on individual risk profiles.

9. References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2020). ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 171: Management of Preterm Labor. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 136(4), e29-e54.

- World Health Organization. (2015). WHO recommendations on interventions to improve preterm birth outcomes. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Roberts D, Brown J, Medley N, Dalziel SR. (2017). Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3:CD004454.

- Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ. (2014). Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science, 345(6198), 760-765.

- Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Thom EA, Blackwell SC, et al. (2016). Antenatal betamethasone for women at risk for late preterm delivery. New England Journal of Medicine, 374(14), 1311-1320.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. (2017). SMFM Statement: Implementation of the use of antenatal corticosteroids in the late preterm birth period in women at risk for preterm delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 216(2), B13-B17.

- Sentilhes L, Sénat MV, Ancel PY, et al. (2017). Prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: Guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF). European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 210, 217-224.

- Conde-Agudelo A, Díaz-Rossello JL. (2016). Kangaroo mother care to reduce morbidity and mortality in low birthweight infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 8:CD002771.

- Doyle LW, Crowther CA, Middleton P, Marret S, Rouse D. (2009). Magnesium sulphate for women at risk of preterm birth for neuroprotection of the fetus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1:CD004661.

- Vogel JP, Oladapo OT, Manu A, Gülmezoglu AM, Bahl R. (2015). New WHO recommendations to improve the outcomes of preterm birth. The Lancet Global Health, 3(10), e589-e590.

- Esplin MS, Elovitz MA, Iams JD, et al. (2017). Predictive accuracy of serial transvaginal cervical lengths and quantitative vaginal fetal fibronectin levels for spontaneous preterm birth among nulliparous women. JAMA, 317(10), 1047-1056.

- Flenady V, Wojcieszek AM, Papatsonis DN, et al. (2014). Calcium channel blockers for inhibiting preterm labour and birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6:CD002255.

- Jarde A, Lutsiv O, Park CK, et al. (2019). Preterm birth prevention in twin pregnancies with progesterone, pessary, or cerclage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG, 126(8), 1030-1037.

- Berghella V, Saccone G. (2019). Cervical assessment by ultrasound for preventing preterm delivery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9:CD007235.

- Crowther CA, McKinlay CJ, Middleton P, Harding JE. (2015). Repeat doses of prenatal corticosteroids for women at risk of preterm birth for improving neonatal health outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7:CD003935.