Ruptured Uterus Management

Table of Contents

1. Introduction to Ruptured Uterus

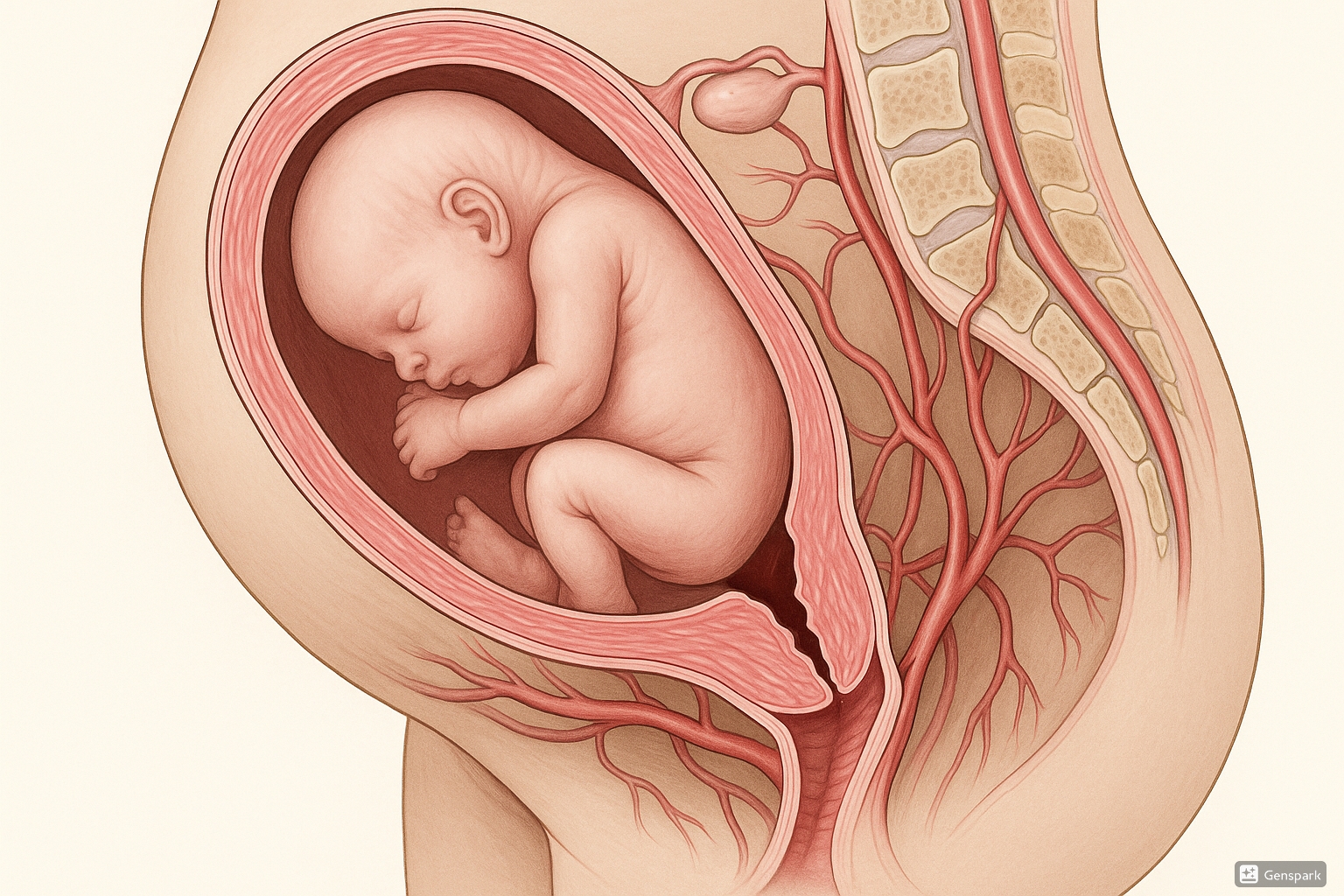

A ruptured uterus is a rare but life-threatening obstetric emergency characterized by a complete or partial tear in the uterine wall that extends into the peritoneal cavity. This condition demands immediate recognition and intervention to prevent maternal and fetal mortality. As nursing professionals, understanding the comprehensive management of ruptured uterus is critical for effective participation in multidisciplinary emergency care.

1.1 Definition

Uterine rupture refers to a full-thickness disruption of all layers of the uterine wall, including the serosa, myometrium, and endometrium. This catastrophic tearing creates a direct communication between the uterine and peritoneal cavities, potentially resulting in fetal displacement into the abdomen, severe hemorrhage, and shock.

It’s important to distinguish uterine rupture from uterine dehiscence, which involves separation of a pre-existing uterine scar that doesn’t extend through all layers and typically presents with less severe clinical manifestations.

1.2 Epidemiology

The overall incidence of uterine rupture varies significantly based on geographic location, healthcare resources, and population characteristics:

- In developed countries: 0.7-1 per 1,000 deliveries

- In developing countries: 1.7-6.2 per 1,000 deliveries

- For scarred uterus (previous cesarean delivery): 0.5-1.7% during trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC)

- For unscarred uterus: Extremely rare at 0.006% (≈ 1 in 17,000 deliveries)

While uterine rupture is rare, its mortality rate can be up to 10-40% in low-resource settings. Even in high-resource environments, it carries a perinatal mortality rate of approximately 6% and significant maternal morbidity.

2. Classification of Uterine Rupture

Uterine rupture can be classified based on several factors, including completeness, anatomical location, etiology, and timing of occurrence. Understanding these classifications facilitates appropriate management approaches.

| Classification Type | Categories | Description |

|---|---|---|

| By Completeness | Complete Rupture | Full-thickness tear through all three layers of uterine wall (endometrium, myometrium, serosa) |

| Incomplete Rupture (Dehiscence) | Partial separation of uterine wall layers, typically involving separation of a previous scar | |

| By Anatomical Location | Lower Segment | Most common location, particularly in scarred uteri, associated with previous cesarean delivery |

| Upper Segment | More common in unscarred uteri; associated with obstructed labor or excessive uterine stimulation | |

| Lateral Rupture | Involves uterine arteries, resulting in more severe hemorrhage | |

| By Etiology | Traumatic | Caused by direct injury, obstetric manipulations, or external trauma |

| Spontaneous | Occurs without apparent external trauma, typically due to intrinsic risk factors | |

| By Timing | Antepartum | Occurring before onset of labor |

| Intrapartum | Occurring during labor (most common) | |

| Postpartum | Occurs after delivery (rare) |

“COMPLETE Rupture” – A mnemonic for identifying complete uterine rupture:

- Catastrophic tear through all layers

- Obvious communication between uterine and peritoneal cavities

- Massive hemorrhage risk

- Peritoneal signs may be present

- Life-threatening emergency

- Emergency surgical intervention required

- Tach symptoms (tachycardia, hypotension)

- Extrusion of fetus may occur

3. Risk Factors for Ruptured Uterus

Multiple factors increase the risk of uterine rupture. Identifying these risk factors is crucial for prevention, early detection, and targeted management of high-risk patients.

Primary Risk Factors

- Previous cesarean delivery – The most significant risk factor, especially with classical (vertical) uterine incisions

- Previous uterine surgery – Myomectomy, hysterotomy, or prior rupture repair

- Trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) – Risk increases with number of previous cesarean deliveries

- Labor induction or augmentation – Particularly with prostaglandins or oxytocin in patients with scarred uteri

- Short interpregnancy interval – Less than 18-24 months after cesarean delivery

Secondary Risk Factors

- Advanced maternal age – ≥35 years

- Obstructed labor – Cephalopelvic disproportion, malpresentation

- Grand multiparity – Five or more previous births

- Uterine anomalies – Congenital structural abnormalities

- Placentation abnormalities – Placenta accreta, increta, percreta

- Uterine overdistension – Multiple gestation, polyhydramnios

- External trauma – Motor vehicle accidents, falls

| Risk Factor | Estimated Risk of Uterine Rupture | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Prior classical (vertical) cesarean | 4-9% | Avoid TOLAC; schedule elective cesarean |

| Prior low transverse cesarean | 0.5-0.9% | Careful selection for TOLAC; close monitoring |

| TOLAC with induction (prostaglandins) | 1.4-2.2% | Avoid prostaglandins in women with uterine scars |

| TOLAC with oxytocin augmentation | 1.1% | Judicious use of oxytocin; close monitoring |

| Interpregnancy interval <18 months | 2-3× increased risk | Family planning counseling; delayed conception |

| Prior myomectomy (enters endometrial cavity) | 0.5-1.0% | Consider cesarean delivery depending on incision type |

| Multiple prior cesareans (≥2) | 0.9-3.7% | Avoid TOLAC; schedule elective cesarean |

The risk of uterine rupture increases significantly with labor induction in patients with previous cesarean sections. Current evidence indicates that prostaglandins (particularly misoprostol) should be avoided in women with uterine scars due to a 3-15 fold increased risk of rupture.

4. Pathophysiology of Ruptured Uterus

Understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms of uterine rupture provides insights into its clinical presentation, progression, and management approaches.

Mechanical Factors

The primary mechanism involves excessive stretching and thinning of the myometrium beyond its elastic capacity, resulting in tissue separation and tear.

- Scarred uterus: Rupture typically occurs at the site of previous incisions due to weaker fibrous tissue and impaired elasticity

- Unscarred uterus: Rupture occurs from excessive pressure against fixed points or areas of relative weakness

- Obstructed labor: Prolonged pressure against pelvic structures leads to ischemia, necrosis, and eventual rupture

Physiological Sequence

-

Initial Phase: Excessive myometrial stretching or pressure against a weakened area

- In scarred uteri: Progressive separation of healed scar tissue

- In unscarred uteri: Thinning and weakening of myometrium from prolonged pressure

-

Progressive Phase: Impaired local blood flow and tissue ischemia

- Increased pressure in one area leads to tissue hypoxia

- Reduced elasticity and contractility of affected myometrial segment

-

Acute Tear: Complete separation of myometrial fibers

- Often occurs during a strong contraction

- May extend laterally and involve blood vessels

-

Systemic Response: Bleeding and peritoneal spillage

- Hemorrhage from torn myometrium and blood vessels

- Peritoneal irritation from blood and amniotic fluid

- Sympathetic activation leading to tachycardia, hypotension

The pathophysiologic progression of uterine rupture is often silent until significant damage has occurred. Initial separation may begin hours before clinical symptoms appear, particularly in scarred uteri where dehiscence can evolve gradually before complete rupture occurs.

Pathophysiological Effects

Maternal Effects

- Hemorrhage (major cause of morbidity/mortality)

- Hypovolemic shock

- Peritonitis (if prolonged exposure)

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

- Bladder or bowel injury (adjacent structures)

- Long-term fertility implications

Fetal Effects

- Acute hypoxia from placental separation

- Fetal bradycardia (earliest sign)

- Acidosis from impaired perfusion

- Extrusion into maternal peritoneal cavity

- High risk of perinatal mortality (10-20%)

“RUPTURE” Pathophysiology – A mnemonic for remembering the pathophysiological progression:

- Risk factors create predisposition

- Uterine wall stretching beyond elastic capacity

- Pressure increases against weakened areas

- Tissue ischemia and reduced elasticity develop

- Undermining of structural integrity

- Rupture occurs, usually during contraction

- Emergence of hemorrhage and systemic effects

5. Signs and Symptoms of Ruptured Uterus

The clinical presentation of uterine rupture ranges from subtle findings to catastrophic collapse. Early recognition requires vigilance and awareness of both classic and atypical manifestations.

Uterine rupture is often characterized by a sudden onset of symptoms. The classic triad includes acute abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, and fetal distress. However, the presentation can be variable, and all symptoms may not be present initially.

Cardinal Signs and Symptoms

| Sign/Symptom | Frequency (%) | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Fetal heart rate abnormalities | 70-100% | Most consistent early finding; typically prolonged deceleration or bradycardia |

| Abdominal pain | 60-100% | May be sudden, severe, and persistent between contractions |

| Vaginal bleeding | 50-80% | Often less than expected; bleeding may be concealed in peritoneal cavity |

| Loss of fetal station | 40-60% | Previously engaged presenting part becomes higher or non-palpable |

| Cessation of uterine contractions | 30-50% | Sudden decrease in uterine activity or hyperstimulation preceding rupture |

| Hemodynamic instability | 30-50% | Tachycardia, hypotension from blood loss; may be delayed |

| Palpable fetal parts outside uterine contour | 10-25% | Late finding; indicates complete rupture with fetal extrusion |

Presentation by Clinical Setting

During Trial of Labor After Cesarean (TOLAC)

- Sudden sharp or searing pain at scar site

- Pain persisting between contractions

- Abrupt cessation of contractions

- Fetal heart rate abnormalities (most sensitive sign)

- Vaginal bleeding (may be minimal)

- Regression of fetal station

In Unscarred Uterus (Obstructed Labor)

- Prolonged painful labor preceding rupture

- Bandl’s ring formation (pathological retraction ring)

- Sudden cessation of previously excessive contractions

- Dramatic abdominal pain with tearing sensation

- Signs of shock may develop rapidly

- Maternal collapse in severe cases

Atypical Presentations

Not all uterine ruptures present with classical symptoms. Awareness of atypical presentations is crucial for timely diagnosis:

- Painless rupture – Particularly in women with epidural anesthesia or previous cesarean

- Nonspecific discomfort – Such as chest pain, shoulder pain, or dyspnea from diaphragmatic irritation

- Minimal external bleeding – Concealed hemorrhage into peritoneal cavity may delay diagnosis

- Isolated fetal bradycardia – May be the only initial sign in 10-20% of cases

- Hematuria – May indicate rupture extension into bladder

Fetal heart rate abnormalities, particularly prolonged deceleration or bradycardia, are often the most sensitive and earliest indicators of uterine rupture. In women undergoing TOLAC, continuous electronic fetal monitoring is essential for early detection.

“RUPTURE” Signs and Symptoms – A mnemonic for recognizing uterine rupture:

- Regression of fetal station

- Uterine contractions – cessation or change

- Pain – sudden, sharp, persistent between contractions

- Tachycardia – maternal

- Unusual vaginal bleeding

- Rates abnormal – fetal heart rate

- Evidence of shock

6. Diagnosis of Ruptured Uterus

Prompt and accurate diagnosis of uterine rupture is critical for timely intervention. The diagnosis is primarily clinical, supported by laboratory and imaging studies when time permits.

Clinical Assessment

History

- Presence of risk factors (previous cesarean, uterine surgery)

- Labor characteristics (prolonged, augmented, or induced)

- Sudden onset of pain or change in pain pattern

- History of prior uterine rupture

Physical Examination

- Vital signs (tachycardia, hypotension)

- Abdominal examination (tenderness, rigidity, loss of uterine contour)

- Vaginal examination (bleeding, loss of fetal station)

- Palpation of fetal parts outside uterine cavity

- Cessation of previously effective contractions

Diagnostic Studies

Laboratory Investigations

- Complete blood count: May show decreasing hemoglobin/hematocrit, though initial values may be normal

- Coagulation profile: To assess for disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

- Blood type and crossmatch: Essential for preparing blood products

- Basic metabolic panel: To evaluate renal function and electrolyte status

- Arterial blood gas: In cases of suspected significant hemorrhage

Imaging Studies

- Ultrasonography: May show hemoperitoneum, absent uterine wall, or abnormal fetal position

- CT scan: Usually not performed in acute settings due to time constraints

- MRI: Helpful in non-emergent cases for dehiscence assessment

Note: Imaging studies are typically not performed in acute settings where clinical diagnosis warrants immediate intervention.

Diagnostic Algorithm

-

Initial Assessment

- Risk factor evaluation

- Vital signs monitoring

- Fetal heart rate assessment

- Abdominal examination

-

Recognition of Warning Signs

- Abnormal fetal heart rate tracings

- Acute onset of abdominal pain

- Vaginal bleeding

- Signs of maternal hemodynamic instability

-

Differential Diagnosis

- Placental abruption

- Uterine dehiscence

- Amniotic fluid embolism

- Other causes of acute abdomen in pregnancy

-

Definitive Diagnosis

In most cases, definitive diagnosis is established during emergency laparotomy

| Differential Diagnosis | Distinguishing Features |

|---|---|

| Placental Abruption |

|

| Uterine Dehiscence |

|

| Amniotic Fluid Embolism |

|

| Uterine Tachysystole |

|

In cases of suspected uterine rupture during labor, do not delay definitive treatment for diagnostic confirmation. If clinical suspicion is high, proceed immediately with emergency laparotomy rather than waiting for laboratory or imaging results, as delays significantly increase maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality.

7. Management of Ruptured Uterus

Management of uterine rupture requires a rapid, coordinated multidisciplinary approach. The primary goals are maternal resuscitation, expeditious delivery of the fetus, control of hemorrhage, and surgical repair or hysterectomy as indicated.

7.1 Emergency Response

Immediate Interventions

-

Activate emergency protocol

- Mobilize obstetric, anesthesia, neonatal, and nursing teams

- Activate massive transfusion protocol if significant hemorrhage

-

Maternal resuscitation (ABCs)

- Establish large-bore IV access (two 16-18G catheters)

- Administer crystalloid fluids (Ringer’s lactate/normal saline)

- Obtain blood for type and crossmatch, CBC, coagulation studies

- Supplemental oxygen administration

- Continuous monitoring of vital signs

- Discontinue oxytocin or other uterotonic agents (if in use)

- Position patient in left lateral decubitus position (if not immediately proceeding to surgery)

- Expedite delivery by emergency cesarean if fetus still in utero

Time is crucial in uterine rupture management. The decision-to-delivery interval should ideally be under 30 minutes. Every 10-minute delay in intervention increases the risk of fetal acidosis, neurological injury, and death.

Emergency Protocols

| Protocol Component | Key Elements |

|---|---|

| Team Mobilization |

|

| Equipment Preparation |

|

| Resuscitation Supplies |

|

| Blood Product Preparation |

|

7.2 Surgical Intervention

Definitive management of uterine rupture requires surgical intervention. The approach depends on the rupture extent, patient hemodynamic status, desire for future fertility, and surgical expertise available.

Uterine Repair

Preferred when:

- Patient is hemodynamically stable

- Rupture is uncomplicated (clean edges)

- Minimal tissue damage

- Desire for future fertility

- Adequate surgical expertise available

Surgical approach:

- Multi-layer closure of the defect

- Hemostasis with figure-of-eight sutures

- Assessment of repair integrity

- Evaluation of adjacent structures

Hysterectomy

Indicated when:

- Extensive uterine damage

- Uncontrollable hemorrhage

- Extension to uterine vessels/broad ligament

- Coexisting placenta accreta spectrum

- No desire for future fertility

- Unstable patient requiring definitive control

Surgical approach:

- Total or subtotal hysterectomy depending on clinical scenario

- Careful assessment of bladder and ureters

- Ligation of vascular pedicles

Additional Surgical Considerations

- Damage assessment: Evaluate adjacent organs (bladder, ureters, bowel)

- Hemostatic agents: Consider fibrin sealants or hemostatic matrices for persistent oozing

- Drain placement: May be considered for large defects or concerns about hematoma formation

- B-Lynch suture: May be used for additional hemostasis in cases of atony with repair

- Temporary arterial occlusion: Internal iliac artery ligation or balloon tamponade in cases of severe hemorrhage

Post-Operative Management

- Intensive monitoring in high-dependency or intensive care setting

- Fluid resuscitation and blood product replacement as needed

- Vigilant observation for delayed hemorrhage or coagulopathy

- Prophylactic antibiotics to prevent infection

- Analgesia for pain management

- Thromboprophylaxis once hemostasis is secured

- Monitoring for end-organ dysfunction (renal, hepatic, respiratory)

“REPAIR” Management – A mnemonic for emergency management of uterine rupture:

- Recognize signs and symptoms early

- Emergency response activation

- Primary survey and resuscitation (ABCs)

- Access IV (two large-bore)

- Immediate surgical intervention

- Restore hemodynamic stability (blood products)

Recent evidence supports the use of tranexamic acid (TXA) early in the management of postpartum hemorrhage, including that from uterine rupture. The WOMAN trial demonstrated that administration of TXA (1g IV) within 3 hours of bleeding onset reduced death due to bleeding by about one-third without increasing thromboembolic complications.

8. Nursing Interventions for Ruptured Uterus

Nursing interventions are critical in both prevention and management of uterine rupture. The nurse’s role encompasses monitoring for early signs, assisting with emergency interventions, and providing postoperative care.

8.1 Pre-Rupture Nursing Interventions

Risk Assessment and Monitoring

-

Thorough history taking

- Previous cesarean delivery details (type, number, complications)

- Prior uterine surgeries

- Interpregnancy interval

-

Continuous fetal monitoring during TOLAC

- Recognize patterns suggestive of impending rupture

- Monitor for sudden onset of fetal bradycardia

- Document baseline and ongoing changes

-

Contraction assessment

- Frequency, duration, and intensity

- Evaluate for hyperstimulation

- Monitor response to oxytocin if used

-

Systematic assessment for warning signs

- Abdominal pain pattern changes

- Vaginal bleeding

- Changes in vital signs

- Loss of fetal station

Preventive Nursing Measures

| Nursing Intervention | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Conservative oxytocin protocol during TOLAC | Excessive uterine stimulation increases rupture risk; lower doses and slower titration recommended |

| Maintain appropriate documentation | Facilitates communication between care providers and establishes timeline of events |

| Position changes and mobility support | Promotes optimal fetal positioning and labor progress while reducing pressure on previous scars |

| Hydration and nutritional support | Maintains maternal stamina and prevents dehydration during labor |

| Anxiety reduction techniques | Reduces catecholamine levels which can affect uterine blood flow and contractility |

| Pain assessment with epidural analgesia | Ensures breakthrough pain (potential sign of rupture) is not masked by anesthesia |

Be especially vigilant during transition phase of labor and second stage, as increased intrauterine pressure during pushing may precipitate rupture in at-risk patients. Consider “laboring down” techniques rather than coached pushing in high-risk cases.

8.2 Post-Rupture Nursing Interventions

Intraoperative Nursing Care

-

Emergency preparation

- Assist with rapid transfer to operating room

- Prepare for emergency cesarean delivery

- Establish multiple IV access

- Set up rapid infusion devices

-

Fluid and blood product administration

- Administer crystalloids as ordered

- Prepare and administer blood products per protocol

- Document accurate intake and output

-

Maternal monitoring

- Continuous vital sign assessment

- Monitor for signs of shock or DIC

- Assist with invasive monitoring if needed

-

Medication administration

- Uterotonic agents after repair/delivery

- Tranexamic acid as indicated

- Antibiotics for prophylaxis

-

Neonatal transition support

- Prepare for potential resuscitation

- Coordinate with NICU team

- Facilitate maternal-infant bonding when possible

Postoperative Nursing Care

Physical Care

- Frequent vital sign monitoring q15min for first 2 hours

- Pain assessment and management

- Assessment of uterine tone and fundal height

- Lochia assessment (quantity, color, consistency)

- Wound care and assessment

- Early mobility promotion with assistance

- Monitor for signs of infection

- Strict I&O monitoring

- Laboratory value trending (CBC, coags)

Psychosocial Support

- Emotional support for trauma response

- Facilitate maternal-infant bonding

- Partner/family inclusion in care planning

- Clear communication about what happened

- Grief support if adverse fetal outcome

- Screening for postpartum depression/PTSD

- Patient education regarding future pregnancies

- Referral to support resources

Discharge Planning and Education

-

Warning signs requiring immediate attention

- Excessive vaginal bleeding (soaking >1 pad/hour)

- Signs of infection (fever, foul discharge)

- Severe pain unrelieved by prescribed medications

- Signs of wound infection or dehiscence

-

Activity restrictions

- Gradual resumption of activities

- Lifting restrictions (nothing heavier than infant)

- Driving restrictions until medical clearance

- Pelvic rest for 6-8 weeks

-

Follow-up appointments

- Postoperative visit within 1-2 weeks

- Complete postpartum evaluation at 6 weeks

- Counseling regarding future pregnancies

-

Contraception counseling

- Importance of adequate interpregnancy interval (≥18-24 months)

- Options appropriate for patient’s condition

Documentation is particularly crucial in cases of uterine rupture. Maintain detailed records of all assessments, interventions, and the patient’s responses. These records are vital for ongoing care, potential future pregnancies, and may have medico-legal implications. Include precise timing of events, communications with providers, and patient education provided.

9. Complications of Ruptured Uterus

Uterine rupture can lead to severe immediate and long-term complications for both mother and baby. Early recognition and management of these complications is essential for optimizing outcomes.

Maternal Complications

Immediate

- Hemorrhage – Leading cause of mortality

- Hypovolemic shock – From blood loss

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

- Adjacent organ damage – Bladder, ureters, bowel

- Need for hysterectomy – Loss of fertility

- Need for blood transfusion – Related risks

- Anemia – From acute blood loss

Long-term

- Infertility – From hysterectomy or uterine scarring

- Increased risk in future pregnancies (8.6-42% recurrence)

- Pelvic adhesions – Potential chronic pain

- Psychological trauma – PTSD, postpartum depression

- Fistula formation – Vesicouterine, uterovaginal

- Wound complications – Infection, dehiscence

| Complication | Incidence |

|---|---|

| Maternal mortality | 1-10% (higher in low-resource settings) |

| Hysterectomy | 11-85% (depending on rupture extent) |

| Blood transfusion | 60-90% |

| Bladder injury | 15-20% |

| Infection | 10-30% |

Fetal/Neonatal Complications

Immediate

- Perinatal mortality – 10-20%

- Birth asphyxia – From placental separation

- Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

- Neonatal anemia – From blood loss

- Traumatic injury – During rupture or extraction

- Need for resuscitation and NICU admission

Long-term

- Cerebral palsy and other neurological sequelae

- Developmental delays

- Long-term disability from hypoxic injury

- Sensory impairments

The prognosis for the fetus is directly related to the interval between uterine rupture and delivery. Perinatal mortality increases dramatically when the delivery interval exceeds 17-20 minutes after rupture. This underscores the critical importance of early recognition and immediate intervention.

While maternal survival has improved with modern medical care, the perinatal outcomes remain poor in many cases. The risk of fetal death is approximately 10-20%, with significant neurological morbidity among survivors. Immediate recognition and intervention provides the best chance for favorable outcomes.

Monitoring for Complications

-

Early postoperative period

- Vital signs monitoring q15min for first 2 hours, then q1h

- Fundal assessment and lochia evaluation q1-2h

- I&O monitoring hourly

- Serial hemoglobin/hematocrit checks

- Wound inspection daily

-

Later recovery phase

- Assessment for delayed hemorrhage

- Monitoring for signs of infection

- Evaluation of voiding and bowel function

- Psychosocial assessment

-

Neonatal monitoring

- Continuous monitoring for signs of hypoxic injury

- Serial neurological assessments

- Temperature regulation

- Glucose stability

10. Recovery & Prognosis

Recovery from a uterine rupture is typically prolonged and requires comprehensive care. Prognosis depends on multiple factors, including the extent of rupture, timing of intervention, and pre-existing health status.

Recovery Timeline

Immediate Postoperative (0-48 hours)

- Intensive monitoring

- Pain management

- Fluid and electrolyte balance

- Blood product administration if needed

- Antibiotic therapy

- Urinary catheter management

Early Recovery (3-14 days)

- Transition to oral medications

- Wound care

- Early mobilization

- Nutritional support

- Bowel function resumption

- Initial psychological support

- First postoperative check

Late Recovery (2-12 weeks)

- Gradual return to normal activities

- Complete wound healing

- Psychological adjustment

- Six-week postpartum checkup

- Contraceptive counseling

- Future pregnancy planning

Physical Recovery Considerations

- Wound healing: Extensive uterine repair may take 6-8 weeks for complete tissue healing

- Anemia recovery: May require iron supplementation for 3-6 months

- Pelvic floor recovery: May need physical therapy for optimal healing

- Activity progression: Gradual return to normal activities over 6-12 weeks

Psychosocial Recovery

- Trauma processing: Uterine rupture represents a significant birth trauma that may require professional support

- Grief counseling: Particularly important in cases of adverse neonatal outcomes

- Partner support: Partners may also experience trauma and require support

- Body image concerns: Particularly after hysterectomy or extensive surgery

Prognostic Factors

| Factor | Favorable Prognosis | Poor Prognosis |

|---|---|---|

| Time to intervention | <20 minutes from rupture | >30 minutes from rupture |

| Location of rupture | Lower segment | Upper segment or lateral (involving vessels) |

| Extent of rupture | Localized, clean edges | Extensive, irregular, involving adjacent organs |

| Hemodynamic status | Stable or quick stabilization | Prolonged shock or coagulopathy |

| Surgical expertise | Experienced team available | Limited surgical expertise |

| Healthcare setting | Tertiary center with resources | Limited-resource setting |

Physical recovery after uterine repair typically takes 6-8 weeks, similar to cesarean delivery. However, psychological recovery may take considerably longer. Screening for postpartum depression and post-traumatic stress disorder should be performed at regular intervals throughout the first year postpartum.

11. Future Pregnancies After Uterine Rupture

Counseling regarding future pregnancy is an essential component of care for women who have experienced a uterine rupture. While subsequent pregnancies are possible for those who retain their uterus, they carry significant risks requiring specialized management.

Recurrence Risk

The risk of recurrent uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies varies based on multiple factors:

- Overall recurrence risk: 8.6-42% (wide range reflects variable studies)

- After complete rupture repair: 22-33% if labor allowed

- After dehiscence repair: 6-11% if labor allowed

- With planned cesarean: Reduced to approximately 5% if performed before labor onset

Preconception Counseling

-

Timing of conception

- Minimum recommended interpregnancy interval: 18-24 months

- Allows for complete myometrial healing and restoration of strength

- Reduces risk of placental abnormalities

-

Documentation review

- Obtain complete operative records from previous rupture

- Review repair technique and location/extent of rupture

- Assess concurrent injuries to other structures

-

Risk assessment

- Individualized risk evaluation based on previous rupture characteristics

- Discussion of maternal and perinatal risks

- Mental health assessment for trauma/anxiety

-

Contraceptive planning

- Reliable contraception during healing period

- Options compatible with uterine scarring

Management of Subsequent Pregnancy

Antenatal Care

- Early ultrasound for dating and viability

- Specialized high-risk obstetric care

- Serial growth scans to monitor fetal development

- Monitoring for placenta accreta spectrum (increased risk)

- Consider additional imaging (MRI) to assess scar

- More frequent prenatal visits

- Emotional support and counseling

- Detailed delivery planning

Delivery Planning

- Scheduled cesarean delivery before labor onset (36-37 weeks)

- Delivery at tertiary care center with appropriate resources

- Multidisciplinary team involvement

- Consideration of antenatal corticosteroids if early delivery

- Type and crossmatch blood products in advance

- Detailed surgical plan with experienced surgeon

- Consideration of vertical uterine incision remote from previous rupture

- Intraoperative assessment of previous scar

Trial of labor after previous uterine rupture is generally contraindicated due to the high recurrence risk. Current guidelines from ACOG and RCOG recommend scheduled cesarean delivery before the onset of labor for all women with prior uterine rupture.

Recent evidence suggests that when managed in a tertiary care center with appropriate planning, subsequent pregnancies after uterine rupture can have favorable maternal and fetal outcomes. A 2021 systematic review found that maternal mortality was extremely rare in planned subsequent pregnancies, with good neonatal outcomes when cesarean delivery was performed at 36-37 weeks gestation.

Special Considerations

- After classical (vertical) uterine rupture: Especially high recurrence risk; consider family completion counseling

- After hysterectomy: Discussion of alternative family building options (surrogacy, adoption)

- Multiple previous cesareans + rupture: Consider limiting family size due to compounded risks

- Thin lower uterine segment: If discovered on ultrasound or MRI during pregnancy, may warrant earlier delivery

“AFTER Rupture” – A mnemonic for counseling regarding future pregnancy:

- Adequate interpregnancy interval (≥18-24 months)

- Fertility options discussion

- Tertiary care center for future pregnancies

- Early planning and delivery (36-37 weeks)

- Realistic discussion of recurrence risks

12. Prevention of Ruptured Uterus

Prevention strategies focus on risk identification, appropriate labor management, and judicious decision-making regarding delivery methods, particularly in high-risk populations.

Primary Prevention

-

Reducing primary cesarean delivery rates

- Evidence-based labor management

- Appropriate use of induction

- Patience during labor progress

- Proper assessment of labor dysfunction

- Training in operative vaginal delivery

-

Optimal surgical techniques during cesarean

- Proper uterine incision placement

- Meticulous closure techniques

- Double-layer uterine closure may reduce risk in subsequent pregnancies

-

Family planning services

- Adequate birth spacing (≥18 months after cesarean)

- Reliable contraception for high-risk women

Secondary Prevention

-

Risk stratification for TOLAC candidates

- Individualized risk assessment

- Consider previous uterine incision type

- Prior vaginal deliveries (protective)

- Use of validated prediction models

-

Appropriate selection for TOLAC

- One prior low transverse cesarean

- No other uterine scars or ruptures

- Adequate pelvis

- Ready access to emergency delivery

- Immediate availability of surgical team

-

Contraindications for TOLAC

- Prior classical (vertical) uterine incision

- Prior uterine rupture

- Prior T or J incisions

- Multiple previous cesarean deliveries (relative)

- Unknown uterine scar

Intrapartum Management for Prevention

| Strategy | Rationale | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous electronic fetal monitoring | Early detection of fetal heart rate abnormalities as first sign of rupture | All women attempting TOLAC require continuous monitoring |

| Judicious use of oxytocin | Excessive stimulation increases rupture risk | Lower doses, slower titration, careful monitoring |

| Avoid prostaglandins | 3-15× increased risk of rupture with prostaglandins in scarred uteri | Alternative induction methods if necessary |

| Labor progression monitoring | Prolonged labor may increase risk | Appropriate partogram use; timely intervention for dystocia |

| Pain pattern assessment | Changes in pain characteristics may signal impending rupture | Regular assessment, especially with epidural anesthesia |

| Appropriate facility selection | Immediate surgical capability critical | TOLAC only in facilities with immediate cesarean capability |

Education and System-Level Prevention

-

Healthcare provider education

- Training in recognition of warning signs

- Simulation drills for uterine rupture management

- Education about appropriate labor management

-

Patient education

- Informed consent regarding TOLAC risks/benefits

- Warning signs to report during labor

- Importance of birth spacing after cesarean

-

System improvements

- Clear protocols for high-risk labor management

- Rapid response teams for obstetric emergencies

- Quality improvement initiatives to reduce primary cesarean rates

- Multidisciplinary approach to high-risk cases

Recent guidelines emphasize that TOLAC should only be attempted in facilities with “immediate availability” of appropriate surgical teams and anesthesia personnel. This is generally interpreted as the capability to begin an emergency cesarean delivery within 30 minutes of the decision being made. Women desiring TOLAC in settings that cannot provide this level of responsiveness should be referred to appropriate facilities or counseled regarding scheduled repeat cesarean delivery.

13. Best Practices for Ruptured Uterus Management

Current evidence-based best practices focus on early recognition, rapid response, and coordinated team management of uterine rupture. The following recommendations represent the latest guidance from professional organizations and research.

Best Practice #1: Implement Standardized Protocols and Simulation Training

Evidence shows that institutions with standardized emergency protocols and regular team simulation for uterine rupture have improved outcomes. These protocols should include clear role assignments, communication pathways, and decision trees for rapid intervention.

Recent updates recommend quarterly multidisciplinary simulation training that includes obstetricians, anesthesiologists, nurses, surgical technicians, and blood bank personnel to ensure coordinated emergency response.

Best Practice #2: Early Administration of Tranexamic Acid

The WOMAN trial and subsequent research have demonstrated that early administration of tranexamic acid (within 3 hours of bleeding onset) significantly reduces death due to bleeding in postpartum hemorrhage, including uterine rupture cases.

Current guidelines recommend administering 1g tranexamic acid IV over 10 minutes as soon as significant hemorrhage is identified, with a second dose of 1g if bleeding continues after 30 minutes or recurs within 24 hours.

Best Practice #3: Risk-Appropriate Care Setting for TOLAC

Updated guidelines from ACOG, RCOG, and other professional organizations emphasize that trial of labor after cesarean should only be attempted in facilities capable of performing emergency cesarean delivery with team members immediately available throughout active labor.

Recent data suggests that implementation of these recommendations has contributed to decreased maternal and neonatal morbidity from uterine rupture in high-resource settings, with mortality reduction of up to 60% when proper risk stratification and facility selection are applied.

Additional Evidence-Based Recommendations

Diagnostic Improvements

- Continuous cardiotocography remains the gold standard for detection

- Consider point-of-care ultrasound for rapid assessment when feasible

- Implement standardized assessment tools for high-risk patients

- Utilize electronic alert systems that flag warning sign combinations

Management Updates

- Massive transfusion protocols specific to obstetric hemorrhage

- Consideration of cell salvage technology in appropriate cases

- Balloon tamponade techniques for hemorrhage control

- Enhanced recovery protocols for postoperative care

- Multidisciplinary follow-up care coordination

Quality Improvement Initiatives

-

Documentation and review systems

- Standardized documentation templates for high-risk labors

- Systematic case review of all uterine ruptures

- Root cause analysis to identify prevention opportunities

-

Care bundles implementation

- Hemorrhage risk assessment

- Readiness protocols for emergency cesarean

- Standardized medication dosing and equipment

-

Team communication strategies

- Structured handoffs for high-risk patients

- Closed-loop communication in emergencies

- Debriefing after critical events

Despite technological advances, the most reliable approach to improving outcomes in uterine rupture remains vigilant clinical monitoring and rapid response to subtle signs. Recent studies confirm that facilities with the lowest complication rates from uterine rupture share common features: standardized protocols, regular drills, clear communication pathways, and high-level clinical awareness among all team members.

14. References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2019). ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 205: Vaginal Birth After Cesarean Delivery. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 133(2), e110-e127.

- Hibbard, J. U., Gilbert, S., Landon, M. B., Hauth, J. C., Leveno, K. J., Spong, C. Y., et al. (2006). Trial of labor or repeat cesarean delivery in women with morbid obesity and previous cesarean delivery. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 108(1), 125-133.

- Hofmeyr, G. J., Say, L., & Gülmezoglu, A. M. (2005). WHO systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity: the prevalence of uterine rupture. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 112(9), 1221-1228.

- Sentilhes, L., Vayssière, C., Beucher, G., Deneux-Tharaux, C., Deruelle, P., Diemunsch, P., et al. (2013). Delivery for women with a previous cesarean: guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF). European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 170(1), 25-32.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. (2015). Birth After Previous Caesarean Birth. Green-top Guideline No. 45.

- Gyamfi-Bannerman, C., Gilbert, S., Landon, M. B., Spong, C. Y., Rouse, D. J., Varner, M. W., et al. (2012). Risk of uterine rupture and placenta accreta with prior uterine surgery outside of the lower segment. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 120(6), 1332-1337.

- Motomura, K., Ganchimeg, T., Nagata, C., Ota, E., Vogel, J. P., Betran, A. P., et al. (2017). Incidence and outcomes of uterine rupture among women with prior caesarean section: WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 44093.

- WOMAN Trial Collaborators. (2017). Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet, 389(10084), 2105-2116.

- Fitzpatrick, K. E., Kurinczuk, J. J., Alfirevic, Z., Spark, P., Brocklehurst, P., & Knight, M. (2012). Uterine rupture by intended mode of delivery in the UK: a national case-control study. PLoS Medicine, 9(3), e1001184.

- Holmgren, C., Scott, J. R., Porter, T. F., Esplin, M. S., & Bardsley, T. (2012). Uterine rupture with attempted vaginal birth after cesarean delivery: decision-to-delivery time and neonatal outcome. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 119(4), 725-731.

- Landon, M. B., Spong, C. Y., Thom, E., Hauth, J. C., Bloom, S. L., Varner, M. W., et al. (2006). Risk of uterine rupture with a trial of labor in women with multiple and single prior cesarean delivery. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 108(1), 12-20.

- Al-Zirqi, I., Stray-Pedersen, B., Forsén, L., & Vangen, S. (2016). Uterine rupture after previous caesarean section. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 123(10), 1643-1650.

- Fox, N. S., Gerber, R. S., Mourad, M., Saltzman, D. H., Klauser, C. K., Gupta, S., et al. (2014). Pregnancy outcomes in patients with prior uterine rupture or dehiscence. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 123(4), 785-789.

- Jongen, V. H., Halfwerk, M. G., & Brouwer, W. K. (1998). Vaginal delivery after previous caesarean section for failure of second stage of labour. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 105(10), 1079-1081.

- Bujold, E., & Gauthier, R. J. (2002). Risk of uterine rupture associated with an interdelivery interval between 18 and 24 months. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 100(6), 1279-1283.