Third Stage Labor Complications

Comprehensive Guide for Nursing Students

# Introduction to Third Stage Labor Complications

The third stage of labor begins after the delivery of the baby and ends with the delivery of the placenta. This critical phase typically lasts between 5-30 minutes but can be fraught with potentially life-threatening complications. Understanding these complications is essential for nursing students as timely recognition and intervention are crucial for preventing maternal morbidity and mortality.

This comprehensive guide explores the major complications of the third stage of labor: retained placenta, injuries to the birth canal, and postpartum hemorrhage (PPH). We will delve into the causes, risk factors, assessment, management strategies, and nursing considerations for each complication. Special attention is given to postpartum hemorrhage management techniques including bimanual compression of the uterus, aortic compression, and uterine balloon tamponade.

# Normal Third Stage of Labor

Before exploring complications, it’s essential to understand the normal physiological processes of the third stage of labor:

1. Placental Separation: Following delivery of the baby, the uterus continues to contract, reducing its size. This contraction causes the placental site to decrease in area, leading to separation between the placenta and uterine wall.

2. Placental Descent: After separation, the placenta descends into the lower uterine segment and eventually into the vagina due to continued uterine contractions and possibly maternal pushing efforts.

3. Placental Expulsion: The placenta is expelled through the vagina, typically within 5-30 minutes after delivery of the baby.

Memory Aid: The 3 S’s of Normal Third Stage

Separation → Sliding Down → Showing Out

This represents the normal progression of placental delivery: separation from the uterine wall, sliding down into the vagina, and showing out through the introitus.

The third stage can be managed either expectantly (physiological management) or actively. Active management of the third stage of labor (AMTSL) is recommended by the World Health Organization to prevent PPH and includes:

- Administration of a uterotonic agent (oxytocin is preferred) within 1-2 minutes of birth

- Delayed cord clamping (1-3 minutes after birth)

- Controlled cord traction with counter-traction to the uterus

- Uterine massage after placental delivery

When the normal mechanisms of the third stage are disrupted, complications can arise, leading to potentially serious consequences for the mother.

# 1. Retained Placenta

Retained placenta is a condition where all or part of the placenta or membranes remain in the uterus beyond 30 minutes after the delivery of the baby despite active management. It is a significant cause of postpartum hemorrhage and occurs in approximately 2-3% of vaginal deliveries.

# 1.1 Causes and Risk Factors

| Type | Description | Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Placenta Adherens | Failure of placental detachment due to weak uterine contractions | Uterine atony, prolonged labor, high parity, uterine anomalies |

| Trapped Placenta | Placenta detaches but is trapped behind a closed cervix | Premature cervical contraction, mismanagement of third stage |

| Placenta Accreta Spectrum | Abnormal invasion of placental tissue into the uterine wall | Previous cesarean section, advanced maternal age, placenta previa, previous uterine surgery, multiparity |

| Placenta Accreta | Placental villi attach directly to myometrium | The risk increases with the number of previous cesarean deliveries. With placenta previa and one prior cesarean delivery, the risk is 11%; with placenta previa and ≥3 prior cesarean deliveries, the risk increases to 61%. |

| Placenta Increta | Placental villi invade into the myometrium | |

| Placenta Percreta | Placental villi penetrate through the myometrium to the uterine serosa or beyond | |

| Succenturiate Placenta | Accessory lobe of placenta that may be retained | Congenital anatomical variation |

Memory Aid: “PLACENTA” Causes of Retention

Previous cesarean

Labor complications (prolonged or obstructed)

Atypical uterine anatomy

Contractions inadequate

Excessive placental size

Number of pregnancies (high parity)

Trapped behind closing cervix

Abnormal invasion (accreta, increta, percreta)

# 1.2 Assessment and Diagnosis

Clinical signs that suggest retained placenta include:

- Failure to deliver the placenta within 30 minutes of the baby’s birth with active management

- Incomplete placenta upon examination after delivery

- Continuing vaginal bleeding despite a contracted uterus

- Uterus larger than expected after presumed placental delivery

- Visible placental tissue at the cervical os

Diagnostic measures include:

- Visual Inspection: Careful examination of the delivered placenta for completeness, noting any missing cotyledons or membranes

- Manual Exploration: Digital examination of the uterine cavity

- Ultrasound: Bedside ultrasound can confirm the presence of retained placental tissue

- Laboratory Tests: Complete blood count, coagulation profile, and cross-matching of blood may be performed in preparation for potential hemorrhage

# 1.3 Management Strategies

Management of retained placenta follows a stepwise approach:

1. Conservative Measures:

- Empty bladder (urinary catheterization)

- Position change

- Nipple stimulation to release endogenous oxytocin

2. Pharmacological Management:

- Additional uterotonics (oxytocin 10-40 units in 500 mL IV fluid)

- Nitroglycerin for relaxation of constriction ring (50-100 mcg IV)

3. Manual Removal:

- Performed under anesthesia (spinal, epidural, or general)

- Aseptic technique with one hand in the uterus and the other on the abdomen

- Identify the cleavage plane between placenta and uterine wall

- Use the side of the hand in a sawing motion to separate the placenta

4. Instrumental Evacuation:

- Vacuum aspiration or curettage for small retained fragments

- Must be performed carefully to avoid uterine perforation

5. Surgical Management:

- For placenta accreta spectrum, surgical interventions may include:

- Focal resection of affected myometrium

- Hysterectomy (in severe cases or uncontrolled bleeding)

Warning: Risk of Complications

Manual removal of the placenta carries significant risks, including:

- Uterine perforation

- Infection

- Hemorrhage

- Traumatic damage to the uterus

- Amniotic fluid embolism

Always ensure adequate anesthesia, have blood products available, and perform the procedure with skilled personnel present.

# 1.4 Nursing Considerations

Nursing care for patients with retained placenta includes:

- Monitoring: Closely monitor vital signs, bleeding, and uterine tone

- Intravenous Access: Ensure at least one large-bore IV line (16-18 gauge)

- Fluid Resuscitation: Administer crystalloids as ordered and monitor intake/output

- Medication Administration: Prepare and administer uterotonics as prescribed

- Pain Management: Ensure adequate analgesia for procedures

- Preparation for Procedures: Prepare for manual removal, including positioning and assistance

- Post-Procedure Care: Continue monitoring for bleeding and signs of infection

- Prophylactic Antibiotics: Administer as prescribed to prevent infection

- Emotional Support: Provide explanation and reassurance to the patient

- Documentation: Accurately record all assessments, interventions, and responses

Clinical Pearl

When examining a delivered placenta, remember the “Cotyledon Check”: The maternal surface of a complete placenta should have 15-20 cotyledons arranged in a circular pattern. Count and ensure all lobes are present to help identify potential retained fragments.

# 2. Injuries to the Birth Canal

Birth canal injuries during the third stage of labor can be a significant source of postpartum hemorrhage and morbidity. These injuries encompass damage to any part of the genital tract, including the perineum, vagina, cervix, and uterus. Early recognition and proper management of these injuries are essential to prevent complications.

# 2.1 Perineal Tears

Perineal tears are classified into four degrees based on the extent of tissue involvement:

| Classification | Description | Management |

|---|---|---|

| First-degree tear | Involves only the perineal skin and vaginal mucosa | May not require suturing if hemostasis is adequate; otherwise, simple interrupted sutures |

| Second-degree tear | Extends to the perineal muscles but not the anal sphincter | Layered closure: vaginal mucosa, perineal muscles, and perineal skin |

| Third-degree tear | Extends through the anal sphincter complex: 3a: <50% of external anal sphincter (EAS) torn 3b: >50% of EAS torn 3c: Internal anal sphincter (IAS) also torn |

Requires experienced operator, layered repair with identification and repair of internal and external anal sphincter |

| Fourth-degree tear | Extends through the anal sphincter complex and anal epithelium | Requires experienced operator, layered closure involving anal mucosa, internal sphincter, external sphincter, and perineal muscles |

Memory Aid: “TEARS” Classification

Tissue involvement determines degree

Epithelium only = first degree

And muscles too = second degree

Rectum’s sphincter involved = third degree

Sphincter and rectal mucosa = fourth degree

# 2.2 Vaginal Lacerations

Vaginal lacerations can occur in various locations within the vaginal canal:

- Sidewall Lacerations: Often associated with instrumental deliveries or rapid descent

- Periurethral Lacerations: Can cause urinary symptoms if not properly repaired

- Sulcal Tears: May extend deep into the vaginal fornices

- Paravaginal Hematomas: Can form when vessels are damaged without visible lacerations

Management of vaginal lacerations involves:

- Adequate exposure with assistance, lighting, and positioning

- Identification of the apex of the laceration

- Systematic suturing from apex to introitus

- Careful hemostasis throughout repair

# 2.3 Cervical Lacerations

Cervical lacerations occur in approximately 0.2-1.7% of vaginal deliveries and are often associated with:

- Precipitous labor

- Delivery before complete cervical dilation

- Instrumental deliveries

- Large fetal size

- Previous cervical surgery

Signs of cervical lacerations include:

- Persistent bright red bleeding despite a well-contracted uterus

- Blood that appears regardless of uterine massage

- Vital sign changes indicating blood loss

Management involves:

- Visualization of the cervix using ring forceps and adequate lighting

- Repair with absorbable sutures, typically in a figure-of-eight pattern

- Attention to hemostasis and identification of all tears (often occur at 3 and 9 o’clock positions)

# 2.4 Uterine Rupture

Though rare, uterine rupture is a catastrophic complication that can manifest during labor or the third stage. Risk factors include:

- Previous cesarean delivery or uterine surgery

- Trauma (external or internal)

- Excessive use of uterotonics

- Placenta accreta spectrum

- Obstructed labor

Signs of uterine rupture include:

- Severe, persistent abdominal pain

- Hypovolemic shock

- Loss of uterine contour

- Palpable fetal parts through the abdominal wall

- Hematuria (if bladder is involved)

Management typically requires surgical intervention:

- Immediate laparotomy

- Repair of the rupture if possible

- Hysterectomy may be necessary if repair is not feasible

- Aggressive resuscitation with fluids and blood products

# 2.5 Management of Birth Canal Injuries

General principles for managing birth canal injuries include:

- Initial Assessment:

- Evaluate the extent of bleeding

- Assess maternal vital signs

- Ensure adequate intravenous access

- Cross-match blood if significant bleeding

- Visualization:

- Ensure adequate lighting and exposure

- Position patient appropriately (lithotomy position)

- Use assistants for retraction

- Employ vaginal retractors or speculums as needed

- Analgesia/Anesthesia:

- Ensure adequate pain control before repair

- Options include local infiltration, pudendal block, epidural, or spinal anesthesia

- Repair Technique:

- Identify the extent and anatomy of injuries

- Repair in a systematic fashion, from apex to introitus

- Use appropriate suture material (typically absorbable)

- Ensure anatomical alignment

- Post-Repair Care:

- Continue monitoring for bleeding

- Provide adequate analgesia

- Consider ice packs for perineal injuries

- Maintain catheterization if necessary

# 2.6 Nursing Considerations

Nursing care for patients with birth canal injuries includes:

- Assessment:

- Regular monitoring of vital signs

- Assessment of bleeding (amount, color, presence of clots)

- Evaluation of pain level

- Monitoring urine output

- Interventions:

- Position the patient for optimal visualization during repair

- Assist with the repair procedure

- Administer prescribed medications (antibiotics, pain relief)

- Apply cold therapy to reduce swelling

- Patient Education:

- Perineal care and hygiene

- Signs of infection to monitor

- Pain management techniques

- Activity restrictions

- Pelvic floor exercises when appropriate

- Documentation:

- Location and extent of injuries

- Repair procedures performed

- Medications administered

- Patient response to interventions

Clinical Pearl

The “Rule of Threes” for birth canal injury assessment: Check the perineum and lower vagina, the middle vagina, and the upper vagina/cervix systematically. This three-zone approach helps ensure no injuries are missed during assessment.

# 3. Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH)

Postpartum hemorrhage is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality worldwide, responsible for approximately 25% of all maternal deaths globally. Early recognition and prompt intervention are crucial for preventing severe morbidity and mortality.

# 3.1 Definition and Classification

Traditional definitions of PPH have relied on estimated blood loss thresholds:

- Primary (Early) PPH: Blood loss ≥500 mL following vaginal delivery or ≥1000 mL following cesarean delivery within the first 24 hours after birth

- Secondary (Late) PPH: Excessive bleeding occurring between 24 hours and 12 weeks postpartum

However, more recent approaches recognize that clinical signs of hemodynamic compromise may be more important than absolute blood loss volume. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) defines PPH as “cumulative blood loss ≥1000 mL or bleeding associated with signs/symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours after birth, regardless of delivery route.”

| Classification | Blood Loss | Clinical Signs |

|---|---|---|

| Class I | Up to 15% of blood volume (750-900 mL) | Minimal signs; slight tachycardia |

| Class II | 15-30% of blood volume (900-1800 mL) | Tachycardia (HR >100), tachypnea, decreased pulse pressure |

| Class III | 30-40% of blood volume (1800-2400 mL) | Marked tachycardia (HR >120), tachypnea, altered mental status, hypotension |

| Class IV | >40% of blood volume (>2400 mL) | Profound shock, severe hypotension, confusion/lethargy, anuria |

# 3.2 Causes and Risk Factors

The causes of PPH are often remembered using the mnemonic “4 T’s”:

Memory Aid: The 4 T’s of PPH

Tone: Uterine atony (70-80% of cases)

Trauma: Genital tract trauma (20% of cases)

Tissue: Retained placental tissue or membranes (10% of cases)

Thrombin: Coagulation disorders (rare but serious)

Risk factors for PPH include:

| Antepartum Factors | Intrapartum Factors | Postpartum Factors |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

# 3.3 Assessment and Diagnosis

Early recognition of PPH is critical for effective management. Assessment includes:

- Visual Estimation of Blood Loss: Though subjective and often inaccurate, it remains common practice. Blood loss is frequently underestimated by 30-50%.

- Quantitative Blood Loss Measurement (QBL): More accurate methods include:

- Weighing soaked materials (1 gram = 1 mL blood)

- Calibrated drapes and collection bags

- Pictorial guides for standardized estimation

- Vital Signs Monitoring: Tachycardia, hypotension, and tachypnea may indicate significant blood loss

- Physical Assessment:

- Uterine tone evaluation (firm vs. boggy)

- Inspection of the genital tract for lacerations

- Assessment for signs of retained placental tissue

- Evaluation of bladder fullness

- Laboratory Assessment:

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Coagulation studies (PT, PTT, fibrinogen, D-dimer)

- Crossmatching for potential transfusion

# 3.4 Management Strategies

Management of PPH follows a stepwise approach, beginning with conservative measures and escalating as needed:

1. Initial Measures:

- Call for help and mobilize the PPH team

- Assess vital signs and establish large-bore IV access (16-18 gauge, preferably two lines)

- Begin fluid resuscitation with warmed crystalloids

- Administer oxygen via face mask

- Initiate continuous monitoring of vital signs

- Empty bladder (urinary catheterization)

2. Identify and Treat the Cause:

- Uterine atony: Uterine massage and uterotonics

- Genital tract trauma: Identification and repair

- Retained tissue: Manual exploration and removal

- Coagulation disorders: Blood products and specific factor replacement

3. Medical Management:

- First-line: Oxytocin (10-40 units in 1L IV fluid or 10 units IM)

- Second-line: Ergometrine/Methylergometrine (0.2 mg IM) or Carboprost (Hemabate) (0.25 mg IM, can repeat q15min up to 8 doses)

- Third-line: Misoprostol (800-1000 mcg rectally)

- Tranexamic acid (1g IV over 10 minutes, within 3 hours of birth)

4. Mechanical and Surgical Interventions:

- Bimanual uterine compression

- Aortic compression

- Intrauterine balloon tamponade

- Uterine artery embolization

- Uterine compression sutures (B-Lynch suture)

- Uterine artery ligation

- Hysterectomy (as last resort)

5. Blood Product Replacement:

- Packed red blood cells

- Fresh frozen plasma

- Platelets

- Cryoprecipitate

- Consider massive transfusion protocol for severe hemorrhage

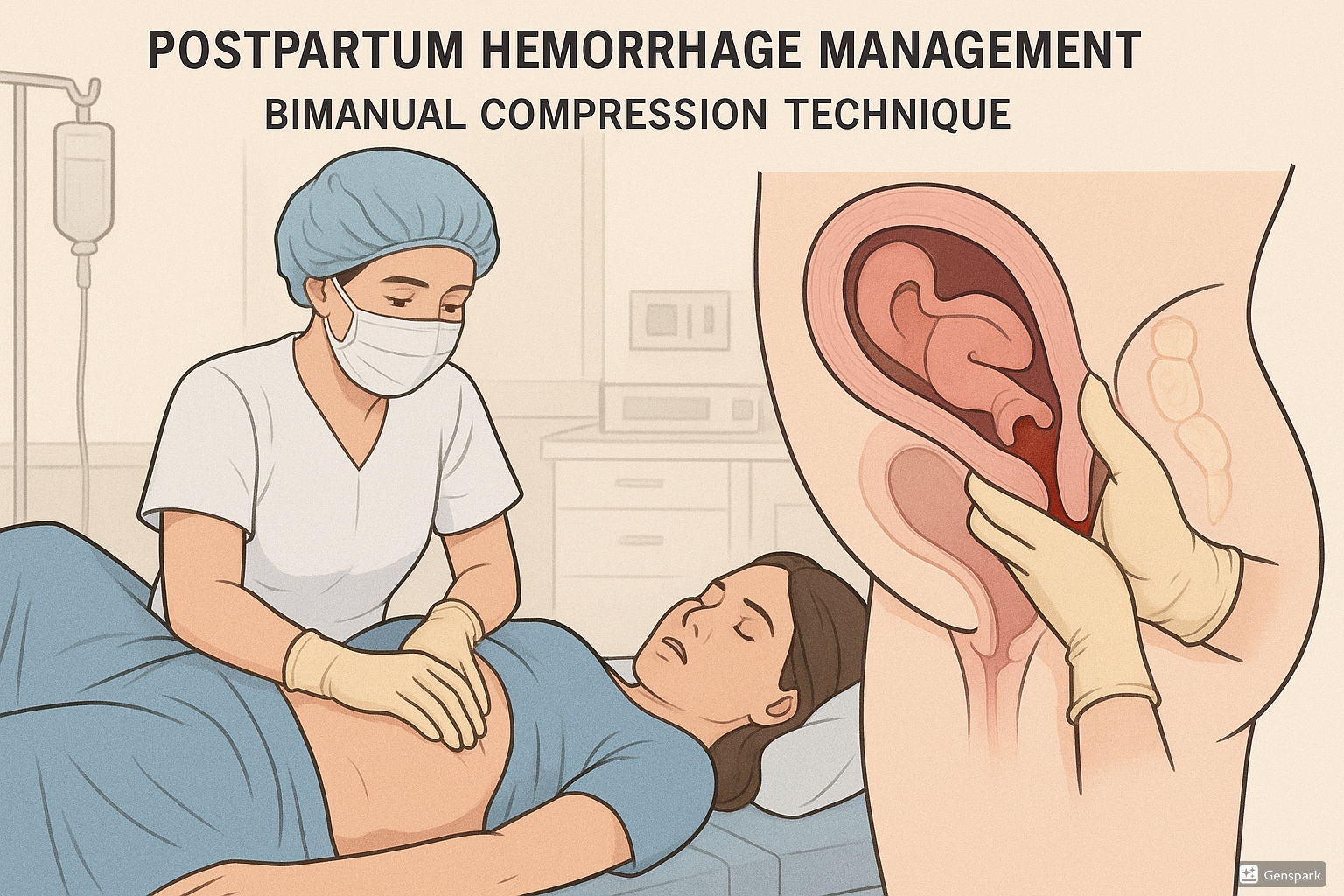

# 3.4.1 Bimanual Compression of the Uterus

Bimanual uterine compression is a critical first-line mechanical intervention for managing PPH due to uterine atony. It’s an effective temporizing measure while preparing for other interventions.

Technique for Bimanual Uterine Compression:

- Empty the bladder (via catheterization if necessary)

- Form one hand into a fist and place it in the anterior vaginal fornix

- Place the other hand on the abdomen, behind the uterine fundus

- Apply firm pressure between both hands, compressing the uterus

- Maintain compression for 5-10 minutes to allow for clot formation and uterine contraction

- Administer uterotonics simultaneously

Clinical Pearl

During bimanual compression, press firmly but avoid excessive force that could cause tissue damage. The pressure should be sustained rather than intermittent. Consider changing operators every 5 minutes if prolonged compression is needed, as the technique is physically demanding.

# 3.4.2 Aortic Compression

Aortic compression is a life-saving emergency measure used in cases of severe hemorrhage to reduce blood flow to the uterus while other interventions are being prepared.

Technique for Aortic Compression:

- Position patient supine with knees slightly flexed

- Locate the aorta by palpating just above and slightly to the left of the umbilicus

- Use the flat part of your fist or the tips of your fingers to compress the aorta against the vertebral column

- Apply firm, downward pressure until femoral pulsations are no longer palpable

- Maintain compression until bleeding is controlled or definitive intervention is available

Important Considerations

- Aortic compression is a temporary measure only

- It can be physically demanding for the provider

- May be difficult in obese patients

- Should not delay other definitive interventions

# 3.4.3 Uterine Balloon Tamponade

Intrauterine balloon tamponade is an effective intervention for the management of PPH when medical management fails. The technique works by creating pressure against the bleeding placental bed and stimulating uterine contraction.

| Type of Balloon | Capacity | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Bakri Balloon | 500 mL | Silicone balloon specifically designed for PPH; drainage port allows monitoring of ongoing blood loss |

| Foley Catheter | 30-80 mL | May be used in emergency situations; multiple catheters may be needed |

| Sengstaken-Blakemore Tube | 300 mL | Originally designed for esophageal varices but can be adapted for uterine tamponade |

| BT-Cath | 500 mL | Similar to Bakri with drainage lumen for blood monitoring |

| Condom Catheter | 300-500 mL | Low-resource alternative; condom tied to a catheter and filled with saline |

Technique for Uterine Balloon Tamponade Placement:

- Ensure empty bladder and clean vaginal field

- Insert the balloon into the uterine cavity under ultrasound guidance if available

- Fill the balloon gradually with warm saline (usually 300-500 mL, depending on the device)

- Monitor bleeding through the drainage channel

- Apply gentle traction to ensure the balloon sits against the lower uterine segment

- Continue uterotonic medications

- Monitor vital signs and bleeding

- Typically left in place for 24-48 hours

- Deflate gradually (in stages) before removal

Memory Aid: “BALLOON” Technique

Bladder emptied first

Aseptic insertion technique

Location confirmed (ultrasound if available)

Liquid fill (warm sterile saline)

Observe for drainage output

Oxytocin infusion continued

Note exact fill volume and time of insertion

# 3.4.4 Pharmacological Management

| Medication | Dosage | Route | Contraindications | Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxytocin | 10-40 units in 1L IV fluid or 10 units IM | IV infusion or IM | None specific | Hypotension, water intoxication with prolonged high doses |

| Ergometrine/ Methylergometrine | 0.2 mg | IM or IV (slowly) | Hypertension, pre-eclampsia, cardiac disease | Hypertension, nausea, vomiting, headache |

| Carboprost (15-methyl PGF2α) | 0.25 mg, can repeat q15min up to 8 doses | IM or intramyometrial | Asthma, active cardiac/pulmonary/renal/hepatic disease | Bronchospasm, hypertension, fever, diarrhea, nausea |

| Misoprostol (PGE1) | 800-1000 mcg | Rectal (sublingual or buccal also options) | None specific | Fever, shivering, diarrhea |

| Tranexamic Acid | 1g over 10 minutes, can repeat in 30 minutes if needed | IV | History of thrombosis, active thromboembolic event | Nausea, vomiting, allergic reaction, thrombotic events |

# 3.4.5 Surgical Management

When medical and mechanical interventions fail to control PPH, surgical interventions become necessary. These are typically performed in a sequential manner, from less to more invasive:

- Uterine Compression Sutures:

- B-Lynch suture: Vertical brace suture that compresses the uterus

- Hayman suture: Modified and simplified version of B-Lynch

- Cho sutures: Multiple square sutures

- Uterine Devascularization Procedures:

- Uterine artery ligation

- Utero-ovarian artery ligation

- Internal iliac (hypogastric) artery ligation

- Interventional Radiology:

- Uterine artery embolization

- Hysterectomy:

- Subtotal hysterectomy (faster, less blood loss)

- Total hysterectomy (may be necessary for cervical/lower uterine segment bleeding)

# 3.5 Nursing Considerations

The nurse plays a critical role in the management of PPH. Key nursing responsibilities include:

- Prevention and Early Recognition:

- Identify risk factors during antepartum and intrapartum care

- Participate in active management of the third stage

- Monitor blood loss accurately using quantitative methods

- Assess vital signs and uterine tone regularly

- Emergency Response:

- Activate rapid response team/code protocols

- Establish large-bore IV access (two lines if possible)

- Draw blood for laboratory studies and cross-match

- Administer oxygen and initiate fluid resuscitation

- Assist with uterine massage and other interventions

- Medication Administration:

- Prepare and administer uterotonics and other medications

- Monitor for side effects and therapeutic response

- Document administration times and doses accurately

- Assistance with Procedures:

- Assist with bimanual compression

- Prepare equipment for balloon tamponade insertion

- Monitor balloon drainage output

- Prepare for operative procedures if needed

- Ongoing Monitoring:

- Assess vital signs frequently (q5-15min during active hemorrhage)

- Monitor output from all drains and catheters

- Assess for signs of continuing blood loss

- Monitor laboratory values and maintain fluid balance sheet

- Emotional Support:

- Provide explanations to the patient and family

- Offer reassurance and presence

- Consider psychological impact of traumatic birth experience

- Documentation:

- Record accurate blood loss estimates

- Document all interventions with times

- Maintain detailed fluid balance records

- Record ongoing assessments

Clinical Pearl

Create a “PPH Emergency Kit” or cart in your labor and delivery unit containing all essential supplies for managing PPH: uterotonics, balloon tamponade devices, extra IV supplies, blood drawing tubes, and a checklist of actions. This can save precious minutes during an emergency.

# 4. Best Practices and Recent Updates

The management of third stage complications continues to evolve. Here are three important recent updates and best practices that nursing students should be aware of:

# 4.1 Enhanced Risk Assessment Protocols

Best Practice: Standardized PPH Risk Assessment

Recent guidelines recommend implementing standardized PPH risk assessment tools at multiple time points:

- On admission for delivery

- Before the onset of the second stage of labor

- Immediately post-delivery

The California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) has developed a comprehensive risk assessment tool that stratifies patients into low, medium, and high risk and recommends specific preventative and monitoring strategies for each level.

Studies have shown that implementing such tools can reduce severe PPH by up to 20% through targeted preventive measures for high-risk patients.

Nurses should advocate for the use of standardized risk assessment tools and ensure that prevention strategies are implemented based on identified risk factors. This includes ensuring adequate supplies of uterotonics are available for high-risk patients and that cross-matched blood is readily accessible if needed.

# 4.2 Simulation-Based Training

Best Practice: Multidisciplinary PPH Simulation

Regular multidisciplinary team training using high-fidelity simulation for PPH emergencies has been shown to improve:

- Team communication

- Response times

- Adherence to protocols

- Technical skill performance

- Patient outcomes

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) now recommend regular simulation drills for obstetric emergencies including PPH.

Facilities that implement quarterly PPH simulations report significant improvements in team performance and reductions in adverse outcomes.

Nursing students should actively participate in simulation training opportunities and understand the importance of clear communication and role clarity during emergencies. Familiarity with the location of emergency equipment and protocols through simulation training can significantly improve response in actual emergencies.

# 4.3 Bundle Approach to PPH Management

Best Practice: Implementation of Safety Bundles

The bundle approach to PPH management has gained widespread acceptance. The ACOG, CMQCC, and the National Partnership for Maternal Safety have developed the Obstetric Hemorrhage Safety Bundle, which includes:

- Readiness: Risk assessment, cart with supplies, protocols, and team education

- Recognition: Quantification of blood loss for all births, active monitoring of vital signs

- Response: Stage-based emergency management protocols with clear roles

- Reporting/Systems Learning: Debriefing, multidisciplinary reviews, and process improvements

Facilities that have implemented this bundle approach have reported up to a 20% reduction in severe maternal morbidity from hemorrhage.

A recent update in 2023 includes the recommendation to use tranexamic acid (TXA) within 3 hours of birth for women with PPH, based on findings from the WOMAN trial.

Nursing students should familiarize themselves with the components of hemorrhage bundles and understand their role within each stage. Knowledge of the location and contents of PPH carts, familiarity with unit-specific protocols, and comfort with quantitative blood loss measurement techniques are essential skills.

# 5. Conclusion

Complications of the third stage of labor represent significant challenges in obstetric care and contribute substantially to maternal morbidity and mortality worldwide. Understanding the pathophysiology, risk factors, assessment strategies, and management approaches for retained placenta, birth canal injuries, and postpartum hemorrhage is essential for all nursing students planning to work in maternal care settings.

Key takeaways from this comprehensive guide include:

- The importance of active management of the third stage of labor to prevent complications

- The critical need for early recognition of abnormal bleeding patterns and prompt intervention

- The value of a systematic approach to assessment and management using established protocols

- The essential role of teamwork and clear communication during obstetric emergencies

- The effectiveness of mechanical interventions such as bimanual compression, aortic compression, and balloon tamponade

- The importance of continuous nursing assessment and documentation throughout the third stage and beyond

As a nursing student, developing proficiency in these skills and knowledge areas will prepare you to be an effective member of the maternal care team and contribute to the safety and wellbeing of mothers during this critical period. Remember that while complications of the third stage can be dramatic and stressful, a calm, organized approach following established protocols can significantly improve outcomes.

# 6. References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2022). Practice Bulletin No. 183: Postpartum Hemorrhage. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 140(2), e110-e128.

- World Health Organization. (2022). WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Evensen, A., Anderson, J. M., & Fontaine, P. (2022). Postpartum Hemorrhage: Prevention and Treatment. American Family Physician, 95(7), 442-449.

- California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative. (2022). OB Hemorrhage Toolkit V 3.0. Retrieved from https://www.cmqcc.org/resources-tool-kits/toolkits/ob-hemorrhage-toolkit

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. (2023). Prevention and Management of Postpartum Haemorrhage: Green-top Guideline No. 52. BJOG, 124(5), e106-e149.

- Dahlke, J. D., Mendez-Figueroa, H., Maggio, L., et al. (2022). Prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage: a comparison of 4 national guidelines. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 213(1), 76.e1-76.e10.

- Weeks, A. (2022). The prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage: what do we know, and where do we go next? BJOG, 122(2), 202-210.

- Shakur, H., Roberts, I., Fawole, B., et al. (2021). Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet, 389(10084), 2105-2116.

- Lalonde, A. (2022). Prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage in low-resource settings. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 117(2), 108-118.

- Su, L. L., Chong, Y. S., & Samuel, M. (2022). Uterotonic agents for preventing postpartum haemorrhage: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4, CD011689.