Umbilical Cord Prolapse: Comprehensive Nursing Notes

A detailed guide for nursing students on assessment, management, and prevention

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Definition

- 3. Pathophysiology

- 4. Types of Cord Prolapse

- 5. Risk Factors

- 6. Signs and Symptoms

- 7. Diagnosis

- 8. Nursing Assessment

- 9. Nursing Interventions

- 10. Prevention Strategies

- 11. Complications

- 12. Prognosis and Outcomes

- 13. Patient Education

- 14. Best Practices

- 15. Case Studies

- 16. References

1. Introduction

Umbilical cord prolapse (UCP) is an obstetric emergency that requires immediate identification and intervention. While rare, occurring in approximately 0.1-0.6% of all births, this condition can lead to significant fetal morbidity and mortality if not promptly managed. As a nursing student, understanding cord prolapse is essential for providing timely, effective care during this critical emergency. The survival rate of the fetus depends largely on early detection and rapid intervention, underscoring the importance of nurses being prepared to recognize and respond to this condition.

Cord prolapse accounts for approximately 10% of all fetal deaths related to labor and delivery complications, highlighting the importance of prompt identification and management.

2. Definition

Umbilical Cord Prolapse (UCP): A condition that occurs when the umbilical cord descends through the cervix ahead of or alongside the fetal presenting part after rupture of membranes, potentially leading to cord compression and compromised fetal circulation.

3. Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of cord prolapse involves the descent of the umbilical cord through the cervix before the presenting fetal part. When the cord becomes compressed between the fetal body and the maternal pelvis, it leads to cord compression, which compromises fetal circulation.

Sequence of Physiological Events:

- When cord compression occurs, blood flow through the umbilical vessels is restricted

- This results in diminished oxygen transport to the fetus

- Hypoxia develops, leading to fetal distress

- Without intervention, progressive hypoxia can lead to acidosis

- Continued cord compression may ultimately result in fetal brain damage or death

The umbilical cord contains three vessels:

- One umbilical vein: Carries oxygenated blood from placenta to the fetus

- Two umbilical arteries: Return deoxygenated blood from the fetus to the placenta

When cord prolapse occurs:

- Initial compression leads to occlusion of the umbilical vein (lower pressure system)

- This causes decreased perfusion to the fetus

- With continued compression, the umbilical arteries (higher pressure) also become occluded

- Complete occlusion results in total cessation of blood flow between fetus and placenta

4. Types of Cord Prolapse

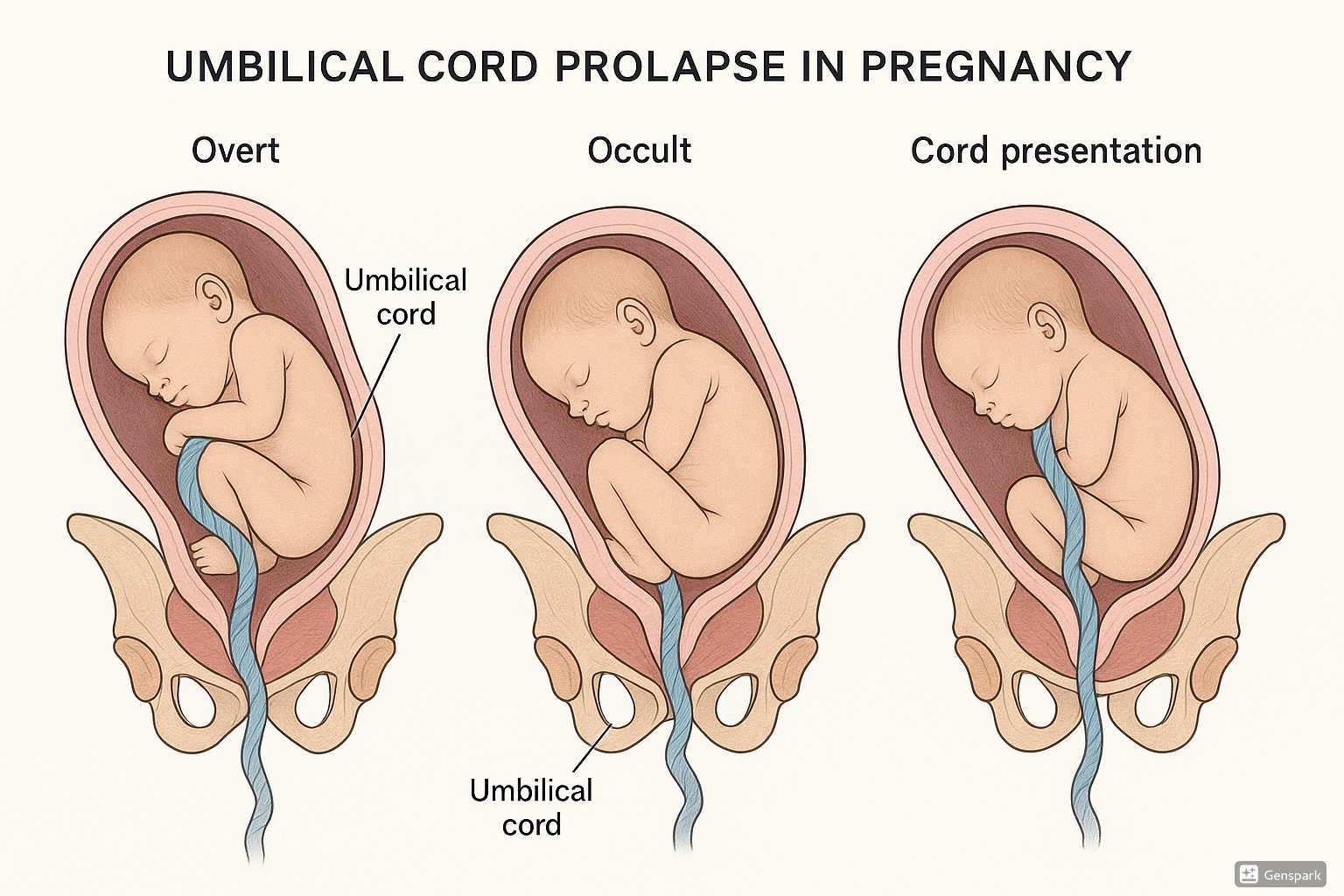

Figure 1: Types of umbilical cord prolapse showing overt prolapse, occult prolapse, and cord presentation

| Type | Description | Visual Presentation | Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overt (Frank) Prolapse | The umbilical cord descends through the cervix and may be visible at or beyond the vaginal opening. | Cord visibly protruding from the vagina or visible on examination | Visual inspection, vaginal examination |

| Occult Prolapse | The cord lies alongside the fetal presenting part but isn’t visible externally or palpable on vaginal examination. | Cord alongside fetal presenting part but not visible | Suspected based on fetal heart rate abnormalities, confirmed with ultrasound or during cesarean |

| Funic Presentation (Cord Presentation) | The cord is positioned between the fetal presenting part and the cervix with membranes intact. | Cord felt through intact amniotic membranes | Vaginal examination with intact membranes, ultrasound |

Important Distinction

While “cord presentation” and “cord prolapse” are sometimes used interchangeably, they represent different conditions. Cord presentation occurs with intact membranes, while cord prolapse happens after membrane rupture.

5. Risk Factors

Understanding the risk factors for cord prolapse is essential for identifying patients who may require closer monitoring and preventive interventions.

Maternal Factors

- Grand multiparity (≥5 previous deliveries)

- Maternal age >35 years

- Contracted or abnormal pelvis

- Previous history of cord prolapse

Fetal Factors

- Non-cephalic presentations (especially footling breech)

- Prematurity (<37 weeks gestation)

- Low birth weight (<2500g)

- Multiple gestation

- Male fetal sex

Obstetric/Procedural Factors

- Artificial rupture of membranes (AROM) with unengaged presenting part

- Unstable lie/malpresentation

- Polyhydramnios

- Long umbilical cord

- External cephalic version

- Second twin delivery

Placental/Amniotic Factors

- Placenta previa

- Funic presentation

- Spontaneous rupture of membranes (SROM) with high presenting part

- Uncontrolled rupture with polyhydramnios

- Abnormal cord insertion (velamentous or marginal)

PROLAPSE Mnemonic for Risk Factors

- P: Prematurity, Polyhydramnios, Presenting part (abnormal)

- R: Rupture of membranes (with unengaged presenting part)

- O: Obstetric maneuvers (e.g., version)

- L: Long cord, Low birth weight

- A: Abnormal presentation (breech, transverse)

- P: Pelvic inadequacy, Previous cord prolapse

- S: Second twin, Sudden rupture of membranes

- E: Engagement failure of presenting part

Clinical Alert

While risk factors help identify at-risk patients, cord prolapse can occur in patients with no identifiable risk factors. Always be vigilant for signs of cord prolapse during labor, particularly after membrane rupture.

6. Signs and Symptoms

The clinical presentation of cord prolapse varies based on the type (overt vs. occult) and severity of the prolapse. Early recognition of these signs is critical for prompt intervention.

- Visible umbilical cord at or beyond the introitus

- Palpable cord on vaginal examination

- Sudden, severe fetal heart rate abnormalities

- May be reported by patient feeling “something coming out”

- No visible or palpable cord

- Fetal heart rate abnormalities (variable decelerations, bradycardia)

- Changes in fetal heart rate with contractions

- May be suspected but difficult to confirm without imaging

Fetal Heart Rate Patterns in Cord Prolapse

| FHR Pattern | Description | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Variable Decelerations | Abrupt decreases in FHR with rapid recovery, varying in timing, depth, and duration | Classic sign of cord compression; deeper and longer decelerations indicate more severe compression |

| Prolonged Deceleration | FHR decrease of ≥15 bpm lasting ≥2 minutes but <10 minutes | May represent ongoing cord compression |

| Bradycardia | Baseline FHR <110 bpm for ≥10 minutes | Indicates severe, sustained cord compression requiring immediate intervention |

| Sinusoidal Pattern | Smooth, sine wave-like pattern with regular oscillations | May develop in cases of prolonged partial cord occlusion and fetal hypoxia |

Remember the VEAL CHOP mnemonic for FHR patterns and their causes:

- Variable decelerations → Cord compression

- Early decelerations → Head compression

- Acceleration → Okay (reassuring)

- Late decelerations → Placental insufficiency

Variable decelerations are the characteristic FHR pattern in cord prolapse due to intermittent cord compression.

7. Diagnosis

The diagnosis of cord prolapse is primarily clinical and requires a high index of suspicion, especially in at-risk patients.

- Visual inspection may reveal the umbilical cord at or beyond the introitus

- Vaginal examination confirms palpable cord ahead of presenting part

- Often accompanied by abnormal fetal heart rate patterns

Note: Visual confirmation makes diagnosis straightforward but requires immediate action.

- Suspected based on abnormal FHR patterns after rupture of membranes

- Variable decelerations or sudden bradycardia without other explanation

- May be confirmed during emergency cesarean delivery

- Ultrasound may identify cord alongside presenting part

Note: More challenging to diagnose and often a diagnosis of exclusion.

Diagnostic Challenge

Occult cord prolapse is particularly challenging to diagnose definitively prior to delivery. When suspected, it should be managed as if confirmed to prevent potential fetal compromise.

8. Nursing Assessment

Comprehensive nursing assessment is crucial for early identification and management of cord prolapse.

Risk Assessment

- Review prenatal record for risk factors

- Assess fetal presentation and station

- Evaluate amniotic fluid volume

- Note timing and method of membrane rupture

Fetal Assessment

- Continuous electronic fetal monitoring

- Evaluate baseline FHR and variability

- Identify periodic changes (decelerations)

- Assess response to uterine contractions

Physical Assessment Findings

- Visual inspection of perineum for visible cord

- Vaginal examination (if indicated) to identify palpable cord

- Assessment of cord pulsation if visible or palpable

- Evaluation of cervical dilation and fetal descent

- Assessment of amniotic fluid for color, odor, amount

- Evaluation of uterine contractions (frequency, duration, intensity)

- Maternal vital signs and emotional status

- Review of labor progress

CORD Assessment Mnemonic

- C: Check cord (visual/palpable) and its pulsation

- O: Observe fetal heart rate patterns

- R: Risk factors evaluation

- D: Document findings and notify provider immediately

When interpreting FHR patterns in suspected cord prolapse:

- Variable decelerations that worsen with contractions are highly suspicious

- Sudden onset of prolonged bradycardia after membrane rupture should trigger immediate evaluation

- Category III tracing (absent variability with recurrent late or variable decelerations, or bradycardia) requires emergency intervention

9. Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for cord prolapse must be initiated immediately as this is an obstetric emergency requiring rapid response to prevent fetal compromise.

Step-by-Step Emergency Management

- Call for help immediately. Activate the emergency obstetric team and notify the obstetrician/midwife.

- Position the mother appropriately:

- Knee-chest position (optimal for reducing pressure on cord)

- Alternatively, Trendelenburg position or elevated hips with pillows

- Avoid supine position

- Manually elevate the presenting part:

- Insert two gloved fingers into the vagina

- Apply upward pressure on the presenting part to lift it off the cord

- Maintain this position until delivery

- Assess cord viability:

- Check for cord pulsation

- Do NOT attempt to replace the cord into the uterus

- If cord is visible externally, cover with sterile saline-soaked gauze to prevent drying and spasm

- Initiate supportive measures:

- Administer oxygen at 8-10 L/min via face mask

- Increase IV fluid rate

- Discontinue oxytocin if running

- Consider tocolysis (e.g., terbutaline) if directed by provider to reduce uterine contractions

- Bladder filling:

- Insert indwelling urinary catheter

- Fill bladder with 500-700ml of normal saline (if ordered)

- This elevates the presenting part off the cord

- Prepare for immediate delivery:

- Emergency cesarean section is typically indicated

- Vaginal delivery may be considered only if fully dilated and imminent

- Prepare for rapid surgical intervention

- Continuous monitoring and documentation:

- Maintain continuous fetal monitoring

- Document all interventions, timing, and fetal heart rate

- Record patient positioning, cord status, and maternal vital signs

The first 30 minutes after cord prolapse diagnosis are critical. The goal is to deliver the baby within this timeframe to minimize hypoxic injury. Nursing actions should focus on:

First 5 Minutes

- Identify prolapse

- Call for help

- Position mother

- Manually elevate presenting part

- Administer oxygen

Next 5-30 Minutes

- Continue elevation maneuvers

- Assist with bladder filling if ordered

- Prepare for emergency delivery

- Transport to operating room

- Support surgical team for delivery

PROLAPSE Intervention Mnemonic

- P: Position mother (knee-chest or Trendelenburg)

- R: Raise presenting part manually

- O: Oxygen administration

- L: Limit cord exposure (cover with moist gauze)

- A: Alert obstetric team immediately

- P: Prepare for emergency delivery

- S: Stop oxytocin infusion

- E: Elevate hips and expedite delivery

Critical Alert

Do NOT:

- Attempt to push the cord back into the uterus

- Delay notification of the obstetric provider

- Leave the patient unattended

- Remove hand from vagina once elevating presenting part

- Allow the cord to become cold, dry, or spastic

10. Prevention Strategies

While cord prolapse cannot always be prevented, certain strategies can reduce the risk, particularly in high-risk pregnancies.

- Early identification of high-risk pregnancies

- Serial ultrasound monitoring for persistent non-cephalic presentations

- External cephalic version (ECV) for breech presentations at appropriate gestational age

- Targeted management of polyhydramnios

- Close monitoring of multiple gestations

- Planned cesarean delivery for certain high-risk presentations

- Avoid artificial rupture of membranes (AROM) when:

- Presenting part not well engaged

- Non-cephalic presentation

- Polyhydramnios present

- Controlled AROM when indicated:

- Perform with presenting part well-applied to cervix

- Use amnihook to create small opening

- Allow slow release of fluid

- Continuous fetal monitoring after membrane rupture in high-risk cases

- Prompt vaginal examination following abnormal FHR after rupture

When performing artificial rupture of membranes in at-risk patients:

- Position patient in slight Trendelenburg

- Use amnihook to create a small puncture high in the amniotic sac

- Allow amniotic fluid to drain slowly and controlled

- Maintain fingers around presenting part to detect early cord prolapse

- Continue to palpate presenting part during and after rupture

This technique may reduce the risk of cord prolapse by preventing sudden, uncontrolled release of amniotic fluid that can carry the cord below the presenting part.

11. Complications

Cord prolapse can lead to significant complications if not promptly diagnosed and managed.

Fetal Complications

- Fetal hypoxia and acidosis

- Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE)

- Neonatal seizures

- Cerebral palsy

- Neurodevelopmental disorders

- Fetal or neonatal death

- Neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission

Maternal Complications

- Trauma related to emergency delivery

- Increased risk of cesarean delivery

- Anesthesia complications from emergency surgery

- Postpartum hemorrhage

- Surgical site infections

- Psychological trauma and birth-related PTSD

| Time from Diagnosis to Delivery | Potential Outcome | Intervention Priority |

|---|---|---|

| < 10 minutes | Typically good fetal outcomes with minimal risk of long-term sequelae | Ideal timeframe; coordinate rapid emergency delivery |

| 10-30 minutes | Increased risk of hypoxic injury; outcome dependent on severity of cord compression | Continue elevation maneuvers; expedite delivery as quickly as possible |

| > 30 minutes | Significantly increased risk of adverse outcomes including HIE, cerebral palsy, or death | Emergency measures for fetal resuscitation; prepare neonatal team for potential resuscitation |

Outcomes Data

Modern management of cord prolapse has significantly improved outcomes. Current perinatal mortality rates are approximately 0.5% with prompt intervention, compared to historical rates of 40-50%. However, the key determinant of outcome remains the time from diagnosis to delivery.

12. Prognosis and Outcomes

The prognosis following cord prolapse is largely dependent on the rapidness of intervention and the duration of cord compression.

Favorable Prognostic Factors

- Prompt recognition and intervention

- Short diagnosis-to-delivery interval (<30 minutes)

- Effective relief of cord compression

- In-hospital occurrence

- Availability of emergency obstetric services

- Term gestation

Unfavorable Prognostic Factors

- Delayed recognition of prolapse

- Prolonged cord compression (>30 minutes)

- Complete cord occlusion

- Out-of-hospital occurrence

- Preterm gestation

- Limited access to emergency obstetric services

Contemporary data on cord prolapse outcomes:

- Overall perinatal mortality: 0.5-2% with modern management (compared to historical rates of 40-50%)

- Neonatal mortality: 3-7% (higher in out-of-hospital settings and premature infants)

- Risk of long-term neurological sequelae: 2-4% with prompt intervention

- NICU admission rate: Approximately 33-50% of infants delivered after cord prolapse

- Cesarean delivery rate: >95% for cord prolapse cases

Improvement Note

The significant improvement in outcomes over the past decades can be attributed to several factors:

- Widespread use of electronic fetal monitoring

- Improved obstetric emergency protocols

- Enhanced neonatal resuscitation capabilities

- Better training for obstetric providers in emergency management

- Implementation of simulation training for obstetric emergencies

13. Patient Education

Patient education is crucial for high-risk patients and for those who have experienced cord prolapse in a previous pregnancy.

Antepartum Education

- Explanation of risk factors and their significance

- Signs to watch for if membranes rupture

- Importance of prompt reporting of:

- Spontaneous rupture of membranes

- Feeling something in the vagina

- Decreased fetal movement

- Discussion of possible need for hospitalization in high-risk cases

- Explanation of emergency procedures if cord prolapse occurs

During Hospitalization

- Explanation of position changes during labor

- Importance of continuous fetal monitoring

- Discussion of why artificial rupture might be avoided or carefully controlled

- Emergency preparedness information

- Psychological support and anxiety reduction

Post-Prolapse Education

- Explanation of what happened and why

- Discussion of implications for future pregnancies

- Postpartum monitoring specific to delivery method

- Signs of potential complications to report

- Emotional support and referral to counseling if needed

- Information on infant follow-up if NICU admission was required

Patient Education Materials: Key Points

- Use clear, non-medical terminology when explaining cord prolapse and its management.

- Provide written information that the patient can review later, especially for high-risk patients.

- Include visual aids when possible to enhance understanding of risk factors and emergency procedures.

- Address emotional concerns and provide reassurance about monitoring and emergency preparedness.

- Ensure patients understand warning signs that require immediate medical attention.

- Provide contact information for questions or concerns.

- Document all education provided in the patient’s chart.

Communication Tip

When educating patients about cord prolapse risk, balance providing important information with avoiding undue anxiety. Focus on the rarity of the condition, the monitoring that will be in place, and the preparedness of the healthcare team to respond to any emergency.

14. Best Practices

Evidence-based best practices in the prevention and management of cord prolapse focus on risk assessment, monitoring, and emergency preparedness.

Training and Preparation

- Regular simulation training for cord prolapse management

- Clearly defined roles in emergency response

- Standardized protocols and algorithms

- Efficient notification systems for obstetric emergencies

- Regular audit of response times and outcomes

- Post-event debriefings for quality improvement

Clinical Practice Guidelines

- Risk assessment tools for identifying high-risk patients

- Protocols for artificial rupture of membranes

- Guidelines for continuous vs. intermittent monitoring

- Decision-making algorithms for emergency delivery

- Communication templates for emergency situations

- Documentation standards for cord prolapse events

Notable international approaches to cord prolapse management:

- United Kingdom (RCOG): Recommends filling the bladder with 500-700ml of normal saline to elevate the presenting part

- Canada (SOGC): Emphasizes the role of in-situ simulation training for all maternity care providers

- Australia (RANZCOG): Promotes the use of standardized emergency call protocols specific to cord prolapse

- Netherlands: Incorporates training for out-of-hospital management for home birth settings

PREPARE Mnemonic for Institutional Readiness

- P: Protocols that are clear and accessible

- R: Regular simulation drills

- E: Equipment readily available

- P: Personnel trained in emergency response

- A: Audit response times and outcomes

- R: Roles clearly defined in emergency situations

- E: Education for all staff levels

15. Case Studies

The following case studies illustrate different presentations and management approaches for cord prolapse scenarios.

Patient Profile: 32-year-old G2P1, 38 weeks gestation, in active labor

Scenario: Patient experienced spontaneous rupture of membranes (SROM) while ambulating. Immediately after, she reported feeling “something come out.” The nurse observed the umbilical cord protruding from the vagina.

Nursing Actions:

- Called for immediate assistance using emergency protocol

- Positioned patient in knee-chest position

- Manually elevated the fetal head with two fingers in the vagina

- Applied oxygen via face mask at 10 L/min

- Discontinued oxytocin infusion

- Increased IV fluid rate

- Covered exposed cord with sterile saline-soaked gauze

- Maintained continuous fetal monitoring; noted FHR of 80 bpm

Outcome:

Emergency cesarean delivery performed within 15 minutes of diagnosis. Apgar scores 6 and 8 at 1 and 5 minutes. No long-term sequelae for the newborn.

Learning Points:

- Importance of immediate recognition and response

- Effectiveness of manual elevation in maintaining fetal oxygenation

- Value of institutional emergency protocols for reducing time to delivery

Patient Profile: 28-year-old G1P0, 39 weeks gestation, induced for post-dates

Scenario: Following artificial rupture of membranes, continuous electronic fetal monitoring showed recurrent variable decelerations that progressively worsened. No visible cord was noted on perineal inspection.

Nursing Actions:

- Alerted provider to concerning fetal heart rate pattern

- Repositioned patient to left lateral position

- Administered oxygen at 10 L/min

- Increased IV fluid rate

- Discontinued oxytocin infusion

- Prepared for vaginal examination by provider

- Assisted with bladder filling via indwelling catheter (500ml normal saline)

- Prepared for emergency cesarean delivery

Outcome:

Occult cord prolapse confirmed during emergency cesarean delivery. Delivery achieved within 23 minutes of suspicious FHR pattern. Apgar scores 4 and 7 at 1 and 5 minutes. Brief NICU stay for observation with full recovery.

Learning Points:

- Recognition of suspicious FHR patterns suggestive of occult prolapse

- Importance of prompt intervention even without visible confirmation

- Value of bladder filling technique when manual elevation not possible

Patient Profile: 35-year-old G3P2, 37 weeks gestation with unstable lie (transverse) and polyhydramnios

Scenario: Patient admitted for monitoring due to high risk status. Decision made for controlled amniotomy prior to planned cesarean delivery to reduce risk of cord prolapse from sudden spontaneous rupture.

Nursing Actions:

- Prepared operating room for immediate cesarean delivery

- Positioned patient in Trendelenburg position for controlled amniotomy

- Assisted with slow, controlled release of amniotic fluid

- Maintained continuous fetal monitoring throughout

- Remained prepared for emergency intervention if needed

- Documented procedure and FHR patterns

Outcome:

Controlled amniotomy performed successfully without cord prolapse. Cesarean delivery completed with good outcomes. Apgar scores 8 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes.

Learning Points:

- Value of preventive strategies in high-risk scenarios

- Importance of anticipating complications before they occur

- Role of controlled procedures in reducing emergency situations

16. References

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. (2014). Umbilical Cord Prolapse (Green-top Guideline No. 50). https://www.rcog.org.uk/guidance/browse-all-guidance/green-top-guidelines/umbilical-cord-prolapse-green-top-guideline-no-50/

- Lin, M. G. (2006). Umbilical cord prolapse. Obstetrical & gynecological survey, 61(4), 269-277.

- Gibbons, C., O’Herlihy, C., & Murphy, J. F. (2014). Umbilical cord prolapse–changing patterns and improved outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 121(13), 1705-1708.

- Holbrook, B. D., & Phelan, S. T. (2013). Umbilical cord prolapse. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics, 40(1), 1-14.

- Siassakos, D., Hasafa, Z., Sibanda, T., Fox, R., Donald, F., Winter, C., & Draycott, T. (2009). Retrospective cohort study of diagnosis–delivery interval with umbilical cord prolapse: the effect of team training. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 116(8), 1089-1096.

- Koonings, P. P., Paul, R. H., & Campbell, K. (1990). Umbilical cord prolapse: a contemporary look. The Journal of reproductive medicine, 35(7), 690-692.

- Murphy, D. J., & MacKenzie, I. Z. (1995). The mortality and morbidity associated with umbilical cord prolapse. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 102(10), 826-830.

- Levy, H., Meier, P. R., & Makowski, E. L. (1984). Umbilical cord prolapse. Obstetrics and gynecology, 64(4), 499-502.

- Kahana, B., Sheiner, E., Levy, A., Lazer, S., & Mazor, M. (2004). Umbilical cord prolapse and perinatal outcomes. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 84(2), 127-132.

- Critchlow, C. W., Leet, T. L., Benedetti, T. J., & Daling, J. R. (1994). Risk factors and infant outcomes associated with umbilical cord prolapse: a population-based case-control study among births in Washington State. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 170(2), 613-618.