Nursing Management of Delirium: A Comprehensive Guide

Evidence-based approach to assessment, care, and rehabilitation

1. Introduction

Delirium is an acute disturbance in attention, awareness, and cognition that develops over a short period of time and tends to fluctuate in severity during the course of a day. As a complex neuropsychiatric syndrome, delirium represents a decompensation of cerebral function in response to one or more pathophysiological stressors. Unlike dementia, delirium is typically reversible if the underlying cause is identified and treated promptly. However, if not properly managed, it can lead to increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs.

Nurses play a crucial role in the prevention, early detection, and management of delirium. This comprehensive guide aims to equip nursing students with the knowledge and tools needed to effectively care for patients experiencing this distressing condition. By understanding the complexities of delirium, nurses can significantly improve patient outcomes and reduce the burden of this condition on both patients and healthcare systems.

2. Prevalence and Incidence

Delirium is a common condition, particularly among hospitalized elderly patients. Understanding the epidemiology of delirium helps nursing professionals recognize high-risk populations and settings for targeted prevention and intervention strategies.

| Setting | Prevalence | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Wards (Elderly Patients) | 50-55% | Higher in patients aged 65+ years [1] |

| Intensive Care Units | 60-80% | Highest in mechanically ventilated patients |

| Emergency Departments | 15-20% | Often underdiagnosed in busy ED settings [2] |

| Nursing Homes | 12-24% | Higher rates in rehabilitation facilities [3] |

| Palliative Care | 35-42% | Increases to 88% in the final days of life |

| Post-Surgical | 15-53% | Higher after cardiac and orthopedic surgeries |

Studies indicate significant variations in delirium prevalence based on setting, with hospital-based point prevalence ranging from 16.4% in morning assessments to 17.9% in evening assessments [4]. This demonstrates the fluctuating nature of delirium throughout the day, underscoring the importance of repeated assessments by nursing staff.

Clinical Pearl

Despite its high prevalence, studies show that nurses identify delirium in only 19% of overall observations and in only 31% of patients where it is present. This emphasizes the need for improved education and standardized screening tools in nursing practice. [5]

3. Classification

Delirium is classified in several ways. Understanding these classifications helps nurses identify the specific presentation and tailor appropriate interventions.

A. Motor Subtypes

| Subtype | Clinical Presentation | Prevalence | Nursing Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperactive | Restlessness, agitation, hallucinations, increased psychomotor activity, combativeness | 25-30% | More easily recognized but requires vigilant safety precautions to prevent injury |

| Hypoactive | Lethargy, decreased responsiveness, apathy, reduced mobility, slowed speech | 25-43.5% | Often missed or misdiagnosed as depression or fatigue; requires active screening [6] |

| Mixed | Fluctuation between hyperactive and hypoactive features | 52.5% | Requires consistent monitoring for changing presentations |

| No Subtype | Normal psychomotor behavior with cognitive impairment | ~5% | Most difficult to detect; relies on cognitive assessment |

B. Based on Etiology

- Substance-induced delirium: Caused by medication side effects, toxins, or substance withdrawal

- Delirium due to general medical condition: Caused by underlying physiological condition or illness

- Delirium due to multiple etiologies: Resulting from a combination of factors

- Delirium not otherwise specified: When the cause cannot be determined

C. ICD-11 Classification

The ICD-11 categorizes delirium under “Neurocognitive Disorders” and includes:

- 6D70 Delirium – with subcategories based on causes

- 6D70.0 Delirium due to disease classified elsewhere

- 6D70.1 Delirium due to substances

- 6D70.2 Delirium due to multiple etiological factors

- 6D70.Z Delirium, cause unspecified

Clinical Pearl

Hypoactive delirium is associated with worse outcomes despite being less disruptive on the unit. Nurses should maintain a high index of suspicion for this “quiet” form of delirium, especially in elderly patients showing increased lethargy or withdrawal. [7]

4. Etiology and Pathophysiology

Delirium results from complex interactions between predisposing factors (vulnerability) and precipitating factors (stressors). Understanding this interplay allows nurses to identify at-risk patients and implement preventive strategies.

Predisposing Factors

Mnemonic: “A FRAGILE MIND”

A – Age (>65 years)

F – Functional impairment (decreased mobility, ADL dependence)

R – Recent hospitalization or surgery

A – Alcohol or drug abuse

G – Gender (male)

I – Impaired cognition (dementia, stroke, Parkinson’s)

L – Laboratory abnormalities (baseline)

E – Emotional disturbances (depression, anxiety)

M – Malnutrition

I – Impaired senses (vision, hearing)

N – Numerous comorbidities

D – Drugs (polypharmacy)

Precipitating Factors

Mnemonic: “I WATCH DEATH”

I – Infections (UTI, pneumonia, sepsis)

W – Withdrawal (alcohol, sedatives)

A – Acute metabolic disorders (electrolyte imbalances, hypoglycemia)

T – Trauma (fractures, surgery, head injury)

C – CNS pathology (stroke, bleeding, seizures)

H – Hypoxia (respiratory failure, anemia, heart failure)

D – Deficiencies (vitamins B1, B12, folate)

E – Endocrine disturbances (thyroid, adrenal)

A – Acute vascular events (MI, shock)

T – Toxins/drugs (anticholinergics, opioids, sedatives)

H – Heavy metals and environmental toxins

Pathophysiological Mechanisms

Multiple mechanisms contribute to the development of delirium:

| Mechanism | Description | Nursing Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Neurotransmitter Imbalance | Decreased acetylcholine and/or excess dopamine, norepinephrine, and glutamate | Monitor for anticholinergic medication effects |

| Neuroinflammation | Systemic inflammatory response causing microglial activation and pro-inflammatory cytokines | Assess for signs of infection and inflammatory conditions |

| Oxidative Stress | Free radical damage to neural membranes | Ensure adequate oxygenation and nutrition |

| Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption | Increased permeability allowing entry of inflammatory mediators | Monitor for systemic inflammation spreading to CNS |

| Circadian Rhythm Disruption | Abnormal melatonin production and sleep-wake cycles | Implement day-night routines and limit nighttime disruptions |

| Network Disconnectivity | Functional disruption of brain networks, especially frontal-subcortical circuits | Recognize that multiple symptoms arise from disrupted integration |

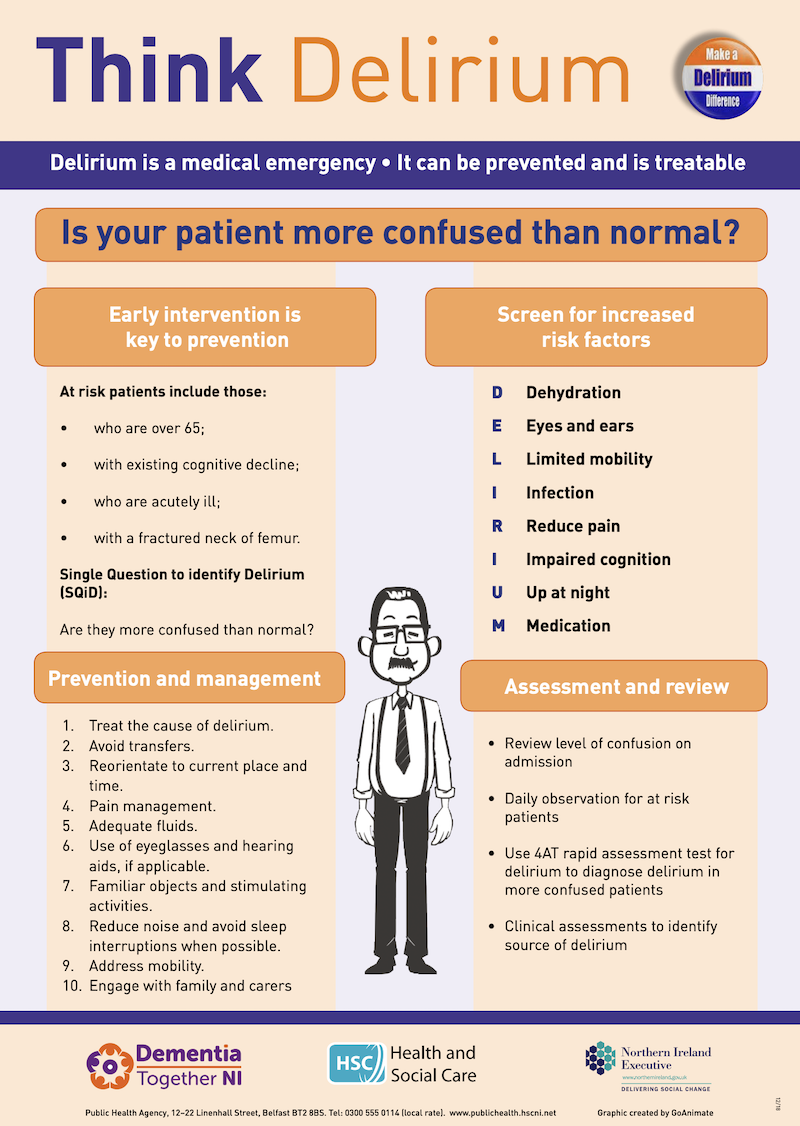

Figure 1: Recognizing the signs and symptoms of delirium

Clinical Pearl

Up to 39% of delirium cases are medication-related. Medications with anticholinergic properties, benzodiazepines, and opioids are the most common culprits. When a patient develops delirium, conducting a thorough medication review should be one of the first nursing actions. [8]

5. Clinical Features

Delirium presents with a variety of clinical features that nurses must recognize for early identification. These features typically develop over hours to days and fluctuate throughout the day, often worsening in the evening (sundowning).

Core Features of Delirium

Mnemonic: “ACUTE BRAIN FAILURE”

A – Altered level of consciousness

C – Cognitive deficits (memory, orientation, language)

U – Unpredictable fluctuations throughout the day

T – Time course: acute onset (hours to days)

E – Emotional disturbances (fear, anxiety, irritability)

B – Behavioral changes (agitation or lethargy)

R – Reduced attention and concentration

A – Altered sleep-wake cycle

I – Impaired perception (illusions, hallucinations)

N – Neurological symptoms (tremors, myoclonus)

F – Fluctuating course

A – Autonomic instability (tachycardia, sweating, flushing)

I – Incoherent thinking and speech

L – Loss of insight

U – Unstable vital signs

R – Reversibility (with proper treatment)

E – Environmental triggers can worsen symptoms

Clinical Manifestations by Subtype

| Feature | Hyperactive Delirium | Hypoactive Delirium | Mixed Delirium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level of Consciousness | Heightened alertness | Reduced alertness, drowsy | Fluctuates between both states |

| Psychomotor Activity | Increased, restlessness, agitation | Decreased, lethargy, minimal movement | Unpredictable shifts |

| Speech | Loud, rapid, pressured | Slow, sparse, delayed responses | Variable |

| Mood | Irritable, hostile, euphoric | Apathetic, withdrawn, depressed | Shifts between extremes |

| Perceptual Disturbances | Prominent hallucinations, delusions | Less obvious or not reported | Present intermittently |

| Risk of Harm | Self-harm, pulling lines, falls | Pressure injuries, aspiration, DVT | Combined risks |

| Recognition by Staff | Easily recognized | Often missed or misdiagnosed | May be partially recognized |

Clinical Pearl

The key distinguishing feature between delirium and other conditions is the acute onset and fluctuating course. A patient who was alert and oriented in the morning but becomes confused in the afternoon should raise immediate concern for delirium and prompt a thorough assessment. [9]

6. Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Accurate diagnosis of delirium involves using structured assessment tools, identifying underlying causes, and distinguishing delirium from other conditions with similar presentations.

Diagnostic Criteria

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the diagnostic criteria for delirium include:

- Disturbance in attention and awareness

- Develops over a short period (hours to days) and tends to fluctuate in severity

- Additional disturbance in cognition (memory, orientation, language, visuospatial ability)

- The disturbances are not better explained by another neurocognitive disorder and do not occur in the context of severely reduced level of arousal (coma)

- Evidence from history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is caused by a medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal, or medication side effect

Differential Diagnosis

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features | Nursing Assessment Clues |

|---|---|---|

| Dementia | Gradual onset over months/years; chronically progressive; stable throughout day; preserved attention; minimal change in level of consciousness | Obtain history from family regarding baseline function; use validated tools to assess for superimposed delirium on dementia |

| Depression | Slower onset; persistent low mood; preserved orientation; intact attention; coherent thinking; lacks fluctuations | Assess mood, affect, and cognitive function; note consistency of symptoms throughout day |

| Psychosis | Longer duration; hallucinations more organized; delusions more fixed; clear consciousness; preserved attention | Evaluate nature of hallucinations/delusions; assess level of consciousness and attention |

| Amnestic Disorder | Isolated memory impairment; preserved attention; no consciousness disturbance; stable course | Test memory alongside attention; assess for other cognitive deficits |

| Intoxication | History of substance use; resolution with clearance of substance; specific toxidrome | Take substance use history; look for specific toxidrome patterns; order toxicology screening |

| Stroke | Sudden onset; focal neurological signs; symptoms stable rather than fluctuating | Perform detailed neurological exam; assess for focal deficits |

| Seizures (Postictal) | History of seizure; confusion improves steadily; not fluctuating | Ask about seizure history; observe for improvement over time |

Mnemonic: “DELIRIUM vs DEMENTIA”

D – Development: Delirium = Acute; Dementia = Gradual

E – Evolution: Delirium = Fluctuating; Dementia = Progressive

L – Level of consciousness: Delirium = Altered; Dementia = Normal

I – Inattention: Delirium = Marked; Dementia = May be present but less severe

R – Reversibility: Delirium = Usually reversible; Dementia = Usually irreversible

I – Illusions/hallucinations: Delirium = Common; Dementia = Less common until late stages

U – Unsteady sleep-wake cycle: Delirium = Severe disruption; Dementia = Often disrupted but less severely

M – Memory: Delirium = Recent and immediate memory affected; Dementia = Recent memory affected first, progresses to remote

Special Considerations: Delirium Superimposed on Dementia (DSD)

Delirium superimposed on dementia (DSD) occurs in 65-89% of hospitalized patients with dementia. Key features suggesting delirium in a patient with dementia include:

- Acute change from baseline mental status

- Increased fluctuation in behavior and cognition

- Newly impaired attention compared to baseline

- Heightened disorganization of thought and speech

- Altered level of arousal (hyper- or hypo-active)

- New-onset perceptual disturbances

Clinical Pearl

When assessing patients with pre-existing cognitive impairment, always ask caregivers, “How is the patient different today from baseline?” This single question can significantly improve detection of superimposed delirium. [10]

7. Nursing Assessment

Comprehensive nursing assessment is critical for early identification and management of delirium. The assessment should be systematic and include history, physical examination, mental status evaluation, and neurological assessment.

7.1 History

A thorough history should include:

- Patient’s baseline cognitive status: Obtain from family members or caregivers

- Onset and course of symptoms: Sudden vs. gradual, fluctuating vs. stable

- Recent changes: Medication changes, environmental changes, hospitalization

- Medical history: Existing conditions that may predispose to delirium

- Medication review: Complete list including over-the-counter drugs and supplements

- Recent procedures or surgeries

- Substance use: Alcohol, recreational drugs, recent cessation

- Sleep patterns: Recent changes, insomnia, day-night reversal

- Pain: Presence, location, severity, management

- Recent infections or illnesses

Mnemonic: “HISTORIES” for Delirium Assessment

H – Hydration status changes

I – Infections (recent or current)

S – Substances (medications, alcohol, drugs)

T – Trauma or surgery

O – Organ failure or disease

R – Restraints (physical or chemical)

I – Immobility

E – Environmental changes

S – Sleep deprivation

7.2 Physical Assessment

Physical assessment should focus on identifying potential physiological causes of delirium:

- Vital signs: Temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation

- Hydration status: Skin turgor, mucous membranes, input/output

- Respiratory assessment: Breath sounds, respiratory effort, oximetry

- Cardiovascular assessment: Heart sounds, peripheral perfusion, edema

- Abdominal assessment: Bowel sounds, distention, tenderness, bladder distention

- Skin assessment: Integrity, color, rashes, pressure areas

- Pain assessment: Location, intensity, behavioral indicators

- Sensory aids: Presence and proper use of glasses, hearing aids

7.3 Mental Assessment

Mental status assessment should be performed using validated tools. Two of the most common are:

| Assessment Tool | Features | Scoring/Interpretation | Nursing Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) |

1. Acute onset and fluctuating course 2. Inattention 3. Disorganized thinking 4. Altered level of consciousness |

Positive if features 1 and 2 AND either 3 or 4 are present | Quick to administer (5 minutes); ideal for regular use in all clinical settings |

| Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) |

1. Acute change or fluctuation in mental status 2. Inattention (using visual or auditory tests) 3. Altered level of consciousness (RASS scale) 4. Disorganized thinking |

Positive if features 1 and 2 AND either 3 or 4 are present | Validated for intubated patients; sensitive (93-100%) and specific (89-100%) [11] |

| 4 A’s Test (4AT) |

1. Alertness 2. AMT4 (abbreviated mental test) 3. Attention (Months Backward test) 4. Acute change/fluctuating course |

0 = Unlikely delirium 1-3 = Possible cognitive impairment ≥4 = Possible delirium |

No special training required; takes less than 2 minutes; useful in various settings |

| Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) | 8 items: Altered level of consciousness, inattention, disorientation, hallucinations, psychomotor agitation/retardation, inappropriate speech/mood, sleep/wake disturbance, symptom fluctuation | 0 = No delirium 1-3 = Subsyndromal delirium ≥4 = Delirium |

Observational tool that can be used over an 8-24 hour nursing shift |

Additional components of mental assessment include:

- Orientation: Person, place, time, situation

- Attention: Digit span, months backward, serial 7s

- Memory: Immediate, recent, and remote recall

- Language: Naming, repetition, comprehension, reading, writing

- Executive function: Abstract thinking, judgment, problem-solving

- Perception: Presence of hallucinations, illusions, or misperceptions

- Thought process: Coherence, logic, organization

7.4 Neurological Assessment

Neurological assessment helps identify focal deficits that might suggest underlying causes:

- Level of consciousness: Using AVPU or Glasgow Coma Scale

- Pupillary response: Size, equality, reaction to light

- Motor function: Strength, coordination, tremors, myoclonus

- Cranial nerve assessment: Especially those related to visual and auditory function

- Reflexes: Deep tendon reflexes, plantar response

- Gait and balance: If safe to assess

- Asterixis: Flapping tremor seen in metabolic encephalopathies

- Autonomic signs: Sweating, tachycardia, blood pressure fluctuations

Clinical Pearl

Nursing documentation should note the specific time of day when delirium symptoms are present or exacerbated. The fluctuating nature of delirium means that a patient might appear perfectly normal during physician rounds but develop severe confusion during evening or night shifts. [12]

8. Treatment Modalities

Treatment of delirium focuses on addressing underlying causes while providing supportive care. A multicomponent approach is most effective in managing delirium.

Addressing Underlying Causes

The primary treatment approach involves identifying and correcting the underlying causes:

- Treating infections

- Correcting metabolic disturbances

- Addressing hypoxia or cardiovascular issues

- Reviewing and modifying medications

- Managing pain effectively

- Treating withdrawal syndromes

- Correcting sensory deficits

- Addressing nutritional and hydration issues

Non-Pharmacological Interventions

| Intervention Category | Specific Measures | Evidence of Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation Strategies | Consistent reorientation, clocks, calendars, family photos, familiar objects, cognitive stimulation | Strong evidence for prevention and management [13] |

| Environmental Modifications | Adequate lighting, noise reduction, maintaining day-night cycle, single room when possible | Reduces incidence by up to 40% when combined with other measures |

| Sleep Promotion | Reduce nighttime disturbances, maintain day-night routine, warm drinks, relaxation techniques | Improves sleep quality and reduces delirium severity |

| Mobility Enhancement | Early and frequent mobilization, physical therapy, range-of-motion exercises | Reduces delirium duration by 1-2 days |

| Sensory Optimization | Ensure glasses and hearing aids are used, adequate lighting, visual and auditory stimulation | Reduces disorientation and misperceptions |

| Hydration and Nutrition | Regular oral intake monitoring, assistance with meals, nutritional supplements | Prevents metabolic triggers of delirium |

| Family Involvement | Family presence, participation in care, familiar communication | Reduces anxiety and improves orientation |

| Pain Management | Regular pain assessment, appropriate analgesia, non-pharmacological pain measures | Uncontrolled pain can trigger or worsen delirium |

Pharmacological Management

Medications should be considered only when non-pharmacological interventions are insufficient, particularly for severely agitated patients who pose a safety risk:

| Medication Class | Examples | Indications | Nursing Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotics (First-Line) | Haloperidol, Risperidone, Olanzapine, Quetiapine | Severe agitation, psychotic symptoms, risk of harm | Monitor QT interval, extrapyramidal symptoms; use lowest effective dose; not for routine use in hypoactive delirium |

| Benzodiazepines | Lorazepam, Diazepam | Alcohol or sedative withdrawal; second-line for severe agitation | May worsen delirium in non-withdrawal states; monitor for respiratory depression |

| Alpha-2 Agonists | Dexmedetomidine, Clonidine | ICU setting for sedation without respiratory depression | Monitor for bradycardia and hypotension |

| Melatonin/Melatonin Receptor Agonists | Melatonin, Ramelteon | Sleep-wake cycle disturbances in delirium | Less evidence but fewer side effects; may help prevent delirium |

Clinical Pearl

Pharmacological interventions should never be the first-line approach for delirium except in cases of alcohol withdrawal or severe agitation with risk of harm. Evidence suggests that antipsychotics do not reduce delirium duration or severity in most cases and may prolong hospitalization. [14]

9. Nursing Management

Nurses play a pivotal role in the prevention, early detection, and management of delirium. Effective nursing management requires a comprehensive, patient-centered approach.

Prevention Strategies

Mnemonic: “PREVENT DELIRIUM”

P – Promote orientation and cognitive stimulation

R – Regular mobilization and physical activity

E – Environmental adaptations (lighting, noise reduction)

V – Vision and hearing optimization (glasses, hearing aids)

E – Ensure adequate sleep and day-night rhythm

N – Nutrition and hydration maintenance

T – Toilet regularly to prevent retention/constipation

D – Discourage use of physical restraints

E – Eliminate unnecessary medications

L – Listen to family about baseline function

I – Infection prevention and prompt treatment

R – Reduce invasive devices when possible

I – Individualize care based on preferences

U – Understand pain management needs

M – Monitor for early signs of delirium

Nursing Interventions for Delirium Management

| Nursing Diagnosis | Interventions | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Acute Confusion related to multifactorial etiology |

– Perform regular delirium assessments every shift – Provide continuous orientation – Encourage family presence – Maintain consistency in care providers – Use clear, simple communication |

– Patient shows improved orientation – Decreased severity of confusion – Reduced episodes of agitation |

| Risk for Injury related to altered cognition and perceptual disturbances |

– Ensure safe environment (bed in lowest position, call bell within reach) – Implement fall precautions – Use bed/chair alarms as needed – Consider one-to-one observation for severe agitation – Avoid physical restraints |

– Patient remains free from injury – No episodes of falls or self-extubation – Safety maintained without restraints |

| Disturbed Sleep Pattern related to neurological dysfunction |

– Maintain day-night differentiation – Reduce nighttime interruptions – Provide comfort measures at bedtime – Avoid caffeine and stimulating activities in evening – Schedule medications to minimize sleep disruption |

– Improved sleep continuity – Decreased nighttime confusion – Normal sleep-wake cycle restored |

| Impaired Physical Mobility related to altered mental status |

– Implement early and progressive mobilization – Provide assistive devices as needed – Encourage range-of-motion exercises – Assist with ambulation at least three times daily – Consult physical therapy |

– Maintenance of baseline mobility – Prevention of complications of immobility – Increased activity tolerance |

| Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity related to altered mental status and immobility |

– Perform regular skin assessments – Implement turning schedule – Use pressure-reducing surfaces – Ensure adequate nutrition and hydration – Manage incontinence promptly |

– Skin remains intact – No development of pressure injuries – Maintenance of tissue perfusion |

| Impaired Verbal Communication related to altered cognition |

– Use simple, clear language – Allow sufficient time for responses – Provide alternative communication methods if needed – Validate patient’s attempts to communicate – Educate family on effective communication strategies |

– Improved communication effectiveness – Reduced frustration during interactions – Enhanced ability to express needs |

| Anxiety related to altered perception and cognitive impairment |

– Provide reassurance and emotional support – Use calm, confident approach – Implement relaxation techniques – Reduce environmental stimuli during periods of anxiety – Educate patient about current situation frequently |

– Decreased manifestations of anxiety – Improved cooperation with care – Reduced episodes of agitation |

Management Based on Delirium Subtype

Nursing interventions should be tailored to the specific subtype of delirium:

Hyperactive Delirium Management

- Create a calm, quiet environment with minimal stimulation

- Assign consistent caregivers

- Remove unnecessary medical equipment

- Avoid physical restraints (increases agitation)

- Consider one-to-one supervision for safety

- Use de-escalation techniques

- Allow family presence to provide reassurance

- Administer medications as prescribed for severe agitation

- Provide adequate personal space

- Anticipate needs to prevent escalation

Hypoactive Delirium Management

- Implement active mobilization schedule

- Provide cognitive stimulation several times daily

- Monitor for aspiration risk during meals

- Implement frequent position changes

- Ensure adequate nutrition and hydration

- Perform active range-of-motion exercises

- Check for urinary retention and constipation

- Provide sensory stimulation (music, conversation)

- Monitor vital signs more frequently

- Anticipate needs as patient may not express them

Clinical Pearl

When communicating with a patient experiencing delirium, use the “validation approach” rather than repeatedly correcting misperceptions. For example, if a patient believes they are at home rather than in the hospital, a validating response might be, “I understand you want to be at home. You’re in the hospital right now, and we’re taking care of you. Your family will visit this afternoon.” [15]

10. Follow-up and Home Care

Delirium effects can persist beyond the acute phase, requiring careful follow-up and home care planning. Approximately 45% of patients with delirium still show symptoms at discharge, and long-term cognitive deficits can persist for 6-12 months in some cases.

Discharge Planning

Effective discharge planning for patients who have experienced delirium includes:

- Comprehensive assessment of cognitive status before discharge

- Medication reconciliation with particular attention to psychoactive medications

- Evaluation of home safety and need for supervision

- Determination of appropriate discharge destination (home, rehabilitation facility, long-term care)

- Assessment of caregiver capabilities and support needs

- Referrals to appropriate community resources and follow-up services

Home Care Strategies for Families

| Area of Focus | Family/Caregiver Strategies |

|---|---|

| Orientation |

– Keep a large, visible calendar and clock – Provide verbal reminders of day, date, and upcoming events – Maintain familiar routines and environment – Display family photos and familiar objects – Avoid unnecessary changes to living space |

| Communication |

– Use simple, clear language – Face the person when speaking – Speak slowly and give time to process – Avoid multiple questions or commands simultaneously – Validate feelings and concerns |

| Environment |

– Ensure adequate lighting, especially at night – Reduce noise and distractions – Maintain comfortable room temperature – Create a safe environment (remove hazards, secure medications) – Consider night lights to prevent disorientation |

| Activities |

– Encourage regular physical activity – Provide appropriate cognitive stimulation – Maintain social interactions – Involve in simple, familiar tasks – Balance activity with adequate rest |

| Sleep |

– Maintain regular sleep-wake schedule – Create relaxing bedtime routine – Limit caffeine and stimulating activities in evening – Ensure comfortable sleeping environment – Consider relaxation techniques before bedtime |

| Nutrition/Hydration |

– Monitor food and fluid intake – Provide frequent, small meals if needed – Encourage regular fluid intake throughout the day – Offer favorite foods to stimulate appetite – Be alert for difficulties with swallowing |

| Medication Management |

– Use medication organizers/reminders – Monitor for medication side effects – Ensure prescriptions are filled and administered as directed – Keep a current medication list – Communicate concerns to healthcare providers |

| Monitoring |

– Watch for signs of recurring delirium – Monitor for new confusion, disorientation, or behavior changes – Track sleep patterns and appetite – Document observations to share with healthcare providers – Know warning signs requiring medical attention |

Warning Signs Requiring Medical Attention

Family members should be educated about signs that require immediate medical attention:

Urgent Medical Attention Needed

- Sudden worsening of confusion

- New onset hallucinations or delusions

- Inability to wake the person

- Severe agitation or aggressive behavior

- Signs of physical illness (fever, pain, breathing changes)

- Refusal to eat or drink for 24+ hours

- New focal neurological symptoms (weakness, slurred speech)

- Fall with or without obvious injury

Contact Provider Within 24 Hours

- Gradual increase in confusion

- Changes in sleep pattern for 2+ days

- Decreased appetite lasting 2+ days

- Increased lethargy

- Subtle behavior changes

- Concerns about medication effects

- New incontinence

- Mild agitation or restlessness

Clinical Pearl

Prior to discharge, provide families with a “delirium information card” that includes basic information about delirium, common triggers that might cause recurrence, warning signs to watch for, and contact information for healthcare providers. This simple tool can significantly reduce readmissions and improve post-discharge care. [16]

11. Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation after delirium focuses on restoring cognitive and physical function and preventing long-term sequelae. Delirium can lead to persistent cognitive deficits, functional decline, and increased dependency.

Cognitive Rehabilitation

Cognitive rehabilitation strategies for post-delirium recovery include:

- Graded cognitive exercises tailored to the patient’s cognitive abilities

- Reality orientation therapy to reinforce awareness of time, place, and person

- Memory training using techniques such as spaced retrieval and association

- Attention training with structured activities that gradually increase in complexity

- Problem-solving exercises to improve executive function

- Computer-based cognitive training programs designed for cognitive rehabilitation

Physical Rehabilitation

Physical rehabilitation addresses deconditioning and functional decline that often occur during and after delirium:

- Progressive mobilization starting with bed mobility and advancing to ambulation

- Strength training targeting muscles affected by immobility

- Balance exercises to reduce fall risk

- Endurance training to improve cardiovascular fitness

- Functional task practice focusing on activities of daily living

- Dual-task training combining cognitive and physical activities

Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation Approach

| Team Member | Role in Delirium Rehabilitation |

|---|---|

| Nurses |

– Continued monitoring for delirium recurrence – Implementation of cognitive stimulation activities – Medication management and monitoring – Education of patient and family – Coordination of care across disciplines – Ongoing assessment of functional status |

| Physicians/Advanced Practice Providers |

– Management of underlying medical conditions – Medication optimization and deprescribing – Ordering appropriate therapies – Monitoring for and treating complications – Long-term follow-up care |

| Physical Therapists |

– Assessment of mobility and function – Development of personalized exercise regimens – Balance and gait training – Strength and endurance training – Recommendations for assistive devices |

| Occupational Therapists |

– ADL assessment and training – Cognitive rehabilitation activities – Environmental adaptations – Energy conservation techniques – Compensatory strategy training |

| Speech-Language Pathologists |

– Cognitive-linguistic assessment and therapy – Swallowing evaluation and management – Communication strategies – Memory aids and techniques – Executive function training |

| Neuropsychologists |

– Comprehensive cognitive assessment – Development of cognitive rehabilitation plans – Management of post-delirium psychological symptoms – Coping strategies for cognitive changes – Family counseling |

| Social Workers |

– Assessment of home environment and support – Coordination of community resources – Financial and insurance guidance – Caregiver support and education – Transition planning |

Innovative Rehabilitation Approaches

Emerging approaches for delirium rehabilitation include:

- Memory Diaries: Collaborative tools where staff and family record events during the delirium episode to help patients process and make sense of their experiences

- Virtual Reality Therapy: Immersive environments for cognitive training and reorientation

- Music Therapy: Using familiar music to stimulate cognition and evoke memories

- Animal-Assisted Therapy: Interaction with therapy animals to reduce stress and promote engagement

- Art Therapy: Creative expression to process delirium experiences and improve cognitive function

- Group Rehabilitation Programs: Peer support and shared experiences in recovery

Measuring Recovery Progress

Regular assessment of recovery is essential for adjusting rehabilitation plans:

- Cognitive Assessment Tools: Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

- Functional Assessments: Barthel Index, Functional Independence Measure (FIM)

- Quality of Life Measures: SF-36, EQ-5D

- Depression and Anxiety Screening: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

- Post-Traumatic Stress Assessment: Impact of Event Scale (IES-R)

Clinical Pearl

Many patients experience significant psychological distress after delirium, including post-traumatic stress symptoms, anxiety, and depression. Asking patients about their delirium experience and providing opportunity to discuss their memories and perceptions can significantly improve psychological recovery. A simple question like “Do you have any memories or dreams from when you were confused in the hospital?” can open important therapeutic conversations. [17]

12. References

- Yazdan-Ashoori, P., et al. (2023). Delirium in Medically Hospitalized Patients: Prevalence, Incidence, and Associated Factors. Journal of Medical Science and Clinical Research. PMC10299512

- Davis, J., et al. (2023). Delirium prevalence in emergency department patients: A systematic review. Nursing in Critical Care. doi:10.1111/nicc.13148

- Morandi, A., et al. (2024). Epidemiology and assessments of delirium in nursing homes and rehabilitation facilities. European Geriatric Medicine. doi:10.1007/s41999-025-01207-x

- Mendiola, D., et al. (2024). Results From the 2023 Cross-Sectional World Delirium Awareness Day Study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. S2667296024000673

- Inouye, S. K., et al. (2001). Nurses’ recognition of delirium and its symptoms: comparison of nurse and researcher ratings. Archives of Internal Medicine. JAMA Internal Medicine

- Krewulak, K. D., et al. (2022). Distribution of delirium motor subtypes in the intensive care unit: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical Care. doi:10.1186/s13054-022-03931-3

- Boettger, S., & Breitbart, W. (2011). Phenomenology of the subtypes of delirium. Palliative and Supportive Care. Cambridge Core

- Clegg, A., & Young, J. B. (2011). Which medications to avoid in people at risk of delirium: a systematic review. Age and Ageing. Oxford Academic

- Marcantonio, E. R. (2017). Delirium in Hospitalized Older Adults. New England Journal of Medicine. NEJM

- Morandi, A., et al. (2017). Detecting Delirium Superimposed on Dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. JAMDA

- Ely, E. W., et al. (2001). The impact of delirium in the intensive care unit on hospital length of stay. Intensive Care Medicine. Springer Link

- American Geriatrics Society. (2015). Clinical Practice Guideline for Postoperative Delirium in Older Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Wiley Online Library

- Hshieh, T. T., et al. (2015). Effectiveness of multicomponent nonpharmacological delirium interventions: a meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine. JAMA Network

- Nikooie, R., et al. (2019). Antipsychotics for Treating Delirium in Hospitalized Adults: A Systematic Review. Annals of Internal Medicine. ACP Journals

- Bélanger, L., & Ducharme, F. (2011). Patients’ and nurses’ experiences of delirium: a review of qualitative studies. Nursing in Critical Care. Wiley Online Library

- Bull, M. J. (2011). Delirium in older adults attending adult day care and family caregiver distress. International Journal of Older People Nursing. Wiley Online Library

- Patel, J., et al. (2014). Post-traumatic stress symptoms in older adults hospitalized for medical illness. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Wiley Online Library