Minor Disorders of Newborn and Its Management

Comprehensive Nursing Care Guide for Neonatal Disorders

Table of Contents

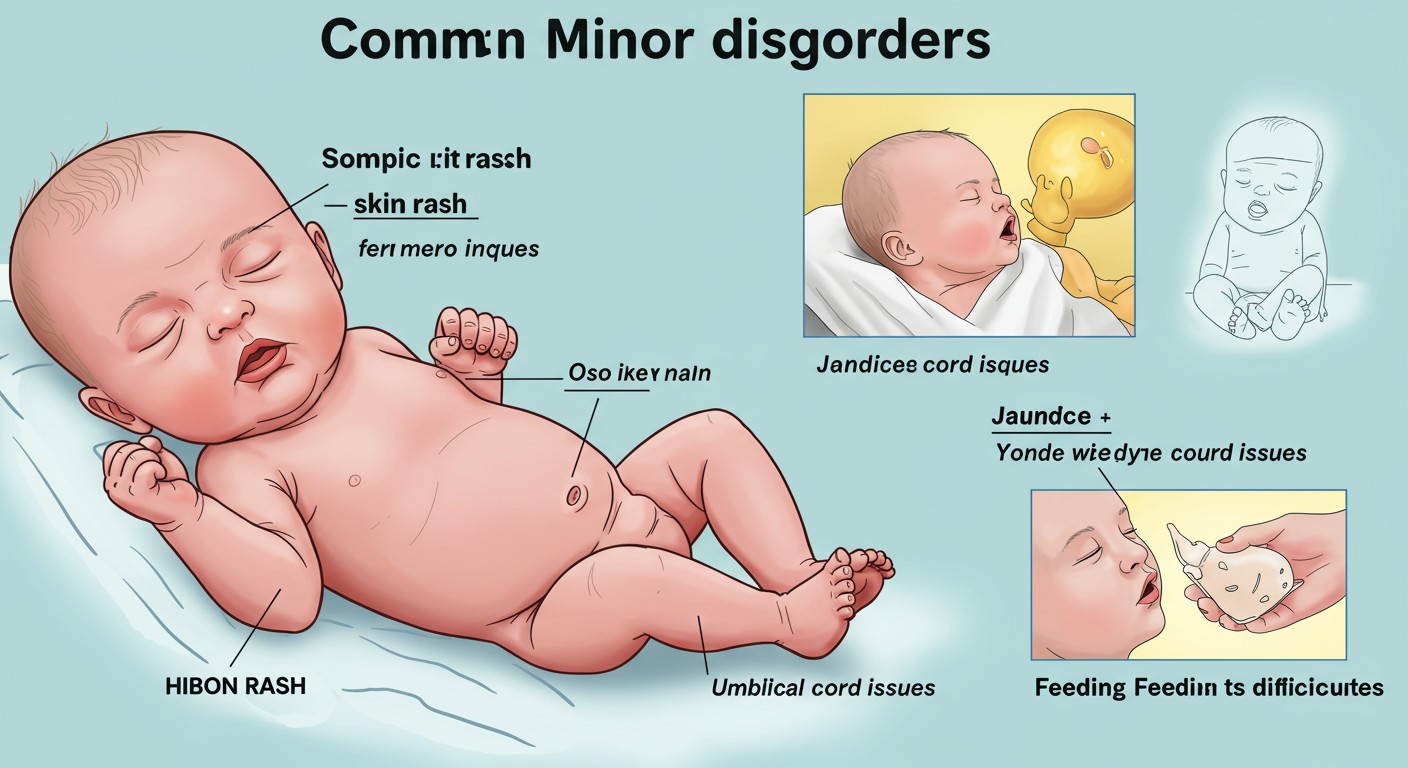

Introduction to Neonatal Disorders

The first 28 days of life, known as the neonatal period, is a critical time of adaptation for newborns. During this transition from intrauterine to extrauterine life, newborns may experience various minor disorders that require careful assessment and management. Understanding these common neonatal disorders is essential for nursing professionals to provide timely and appropriate care.

Most neonatal disorders are transient and self-limiting but require vigilant monitoring to prevent progression to more serious conditions. Early identification and proper management are crucial components of newborn care that directly impact long-term outcomes and family adjustment.

Key Concept:

While most minor disorders of newborns resolve spontaneously, proper nursing assessment and intervention can significantly reduce parental anxiety, prevent complications, and ensure optimal neonatal development.

Objectives of Neonatal Disorder Management

- Early identification of physiological and pathological conditions

- Implementation of prompt and appropriate nursing interventions

- Prevention of complications through vigilant monitoring

- Providing education and reassurance to parents/caregivers

- Promoting newborn comfort and optimal development

Physiological Jaundice

Physiological jaundice is one of the most common neonatal disorders, affecting approximately 60% of term newborns and 80% of preterm newborns. It results from elevated serum bilirubin levels manifesting as yellowish discoloration of the skin and sclera.

Etiology

- Increased RBC breakdown (neonate has higher RBC count)

- Immature liver function with limited conjugation ability

- Increased enterohepatic circulation of bilirubin

- Decreased gut motility delaying bilirubin excretion

Clinical Manifestations

- Yellow discoloration of skin and sclera

- Appears after 24 hours of life in term babies

- Progresses in cephalocaudal direction (head to toe)

- Usually peaks by day 3-5 of life

- Resolves within 7-10 days in term infants

Kramer’s Rule for Jaundice Assessment

Visual assessment of jaundice progression by body region

Assessment

| Assessment Parameter | Normal Findings | Concerning Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | After 24 hours of life | Within first 24 hours (pathological) |

| Progression | Cephalocaudal (head to toe) | Rapid progression reaching extremities |

| Duration | Resolves within 7-10 days (term infants) | Persists beyond 2 weeks in term infants |

| Bilirubin levels | Peak typically < 12-15 mg/dL | Rising > 5 mg/dL in 24 hrs or > 20 mg/dL total |

| Behavior | Normal feeding and activity | Lethargy, poor feeding (sign of kernicterus) |

Management

Phototherapy

Primary treatment for moderate hyperbilirubinemia

- Converts bilirubin to water-soluble photoisomers

- Specific wavelength (blue-green spectrum, 460-490 nm)

- Requires full skin exposure except for eyes and genitalia

- Regular assessment of hydration status and body temperature

Supportive Care

- Promote frequent breastfeeding (8-12 times/day)

- Monitor weight, hydration, and urine output

- Avoid supplementing with water or dextrose water

- Serial bilirubin monitoring as per protocol

- Assess for signs of dehydration

JAUNDICE Mnemonic for Nursing Assessment

J – Jaundice progression (cephalocaudal)

A – Age at onset (after 24 hours is physiological)

U – Urination pattern (monitor output)

N – Nutrition status (feeding frequency)

D – Defecation (stool color and frequency)

I – Intensity of skin color (Kramer’s zones)

C – Clinical behavior (alertness, crying)

E – Evaluate risk factors (prematurity, ABO/Rh)

Nursing Considerations:

- Document the extent of jaundice using Kramer’s rule

- Position infant properly during phototherapy with eye protection

- Increase feeding frequency to promote meconium passage

- Monitor temperature every 2-4 hours during phototherapy

- Educate parents about the condition and its management

- Recognize the difference between physiological and pathological jaundice

Diaper Dermatitis

Diaper dermatitis, commonly known as diaper rash, is a common inflammatory condition affecting the skin in the diaper area. It’s one of the frequently encountered neonatal disorders that can cause discomfort and irritation.

Etiology

- Prolonged exposure to moisture (urine and feces)

- Skin maceration from occlusive diapers

- Chemical irritation from fecal enzymes

- Increased skin pH from ammonia in urine

- Secondary fungal infections (Candida albicans)

- Friction between diaper and skin

Clinical Manifestations

- Erythema and inflammation in diaper area

- Shiny, glazed appearance of affected skin

- Possible papules, vesicles, or scaling

- Candidal infection: satellite lesions beyond main rash

- Discomfort, irritability during diaper changes

Types of Diaper Dermatitis

1. Irritant Contact Dermatitis

Most common type, caused by friction and chemical irritation

• Appears on convex surfaces and skin folds

• Spares the folds in severe cases

2. Candidal Diaper Dermatitis

Caused by Candida albicans overgrowth

• Bright red, sharply demarcated

• Satellite papules and pustules

• Often involves skin folds

3. Seborrheic Diaper Dermatitis

Part of generalized seborrheic dermatitis

• Yellow, greasy scales

• Often seen with cradle cap

Management

| Management Strategy | Implementation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Preventive Measures |

|

Reduces skin exposure to moisture and irritants |

| Barrier Products |

|

Creates protective barrier between skin and irritants |

| Candidal Infection |

|

Treats underlying fungal infection |

| Severe Dermatitis |

|

Reduces inflammation and promotes healing |

Nursing Considerations:

- Assess characteristics and extent of the rash during each diaper change

- Document appearance, location, and progression of rash

- Educate parents on proper diaper changing technique

- Advise against use of baby wipes containing alcohol or fragrance

- Demonstrate application of prescribed medications or barrier creams

- Teach parents to recognize signs of worsening or secondary infection

DIAPER Mnemonic for Prevention

D – Dry skin thoroughly after cleaning

I – Inspect skin regularly for early signs

A – Air exposure to promote healing

P – Protect with barrier creams

E – Eliminate irritants (gentle cleansers only)

R – Regular diaper changes (every 2-3 hours)

Oral Thrush

Oral thrush (oropharyngeal candidiasis) is a common fungal infection in newborns caused by Candida albicans. It’s one of the frequent neonatal disorders that requires proper identification and management to prevent complications and discomfort during feeding.

Etiology

- Overgrowth of Candida albicans (commensal fungus)

- Immature immune system in newborns

- Transmission during vaginal delivery

- Transmission from caregivers or contaminated objects

- Recent antibiotic therapy (alters oral flora)

Clinical Manifestations

- White, curd-like patches on oral mucosa, tongue, and gums

- Patches that cannot be easily wiped off

- Underlying erythematous base when patches are removed

- Feeding difficulties or refusal to feed

- Irritability during and after feeding

- Possible concurrent diaper dermatitis (candidal)

Distinguishing Oral Thrush from Milk Residue

Oral Thrush

Cannot be easily wiped off

Bleeding or redness when scraped

Appears on tongue, buccal mucosa, palate

Associated with feeding difficulties

Milk Residue

Easily wiped away

No underlying redness

Usually on tongue only

No feeding difficulties

Management

| Intervention | Administration | Nursing Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nystatin oral suspension |

|

|

| Miconazole oral gel |

|

|

| Gentian violet (1%) |

|

|

Nursing Considerations:

- Assess oral cavity before and after feeding to differentiate thrush from milk residue

- Demonstrate medication administration technique to parents/caregivers

- Advise treating mother’s nipples if breastfeeding (to prevent reinfection)

- Teach proper hygiene and sterilization of feeding equipment

- Monitor infant’s feeding patterns and weight gain

- Assess for concurrent diaper dermatitis which may indicate systemic candidiasis

Practice Point:

Always instruct parents to complete the full course of antifungal treatment even if thrush appears to have resolved. Premature discontinuation often leads to recurrence that may be more difficult to treat.

Umbilical Cord Issues

The umbilical cord is a critical structure that requires proper care and monitoring after birth. Various umbilical cord issues are common neonatal disorders that nurses must be able to identify and manage appropriately to prevent infections and complications.

Normal Umbilical Cord Changes

- Moist and white/blue at birth

- Begins drying within 24 hours of birth

- Turns black and dry as it mummifies

- Separates naturally within 7-14 days

- Small amount of clear/bloody discharge during separation is normal

Common Umbilical Issues

-

Omphalitis (umbilical infection)

- Erythema and swelling around cord

- Purulent or foul-smelling discharge

- Warmth around umbilical area

- Potential systemic symptoms (fever, lethargy)

-

Umbilical Granuloma

- Small, pink, moist tissue at base after cord separation

- Persistent clear/yellow discharge

- No surrounding erythema or tenderness

-

Umbilical Hernia

- Protrusion at umbilicus during crying or straining

- Usually reducible and painless

- Most resolve spontaneously by age 4-5 years

Umbilical Cord Care Timeline

Birth to Day 1

• Moist, white-blue appearance

• Contains Wharton’s jelly

• Initial cord clamp in place

Days 2-3

• Begins drying and shrinking

• Turns brownish-black

• Cord clamp removed (when dry)

Days 5-7

• Continues mummification process

• Dry, black appearance

• Base may become moist as separation begins

Days 7-14

• Cord separation occurs

• Small amount of discharge normal

• Umbilical area continues healing

Management of Umbilical Issues

| Condition | Management | Nursing Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Normal Cord Care |

|

|

| Omphalitis |

|

|

| Umbilical Granuloma |

|

|

| Umbilical Hernia |

|

|

UMBILICAL Mnemonic for Cord Assessment

U – Unusual odor (sign of infection)

M – Moisture level (should progressively dry)

B – Bleeding (small amount normal during separation)

I – Inflammation of surrounding skin

L – Lack of progressive drying

I – Integrity of surrounding skin

C – Color changes (normal: white → black)

A – Appearance of base after separation

L – Length of time for healing

Umbilical Cord Care Best Practices:

- World Health Organization (WHO) recommends “dry cord care” in most settings

- Keep cord clean and dry

- Expose to air when possible

- No routine application of antiseptics

- In areas with high infection rates, chlorhexidine application may be recommended

- Avoid traditional substances (oils, herbs, animal dung)

- Sponge baths until cord falls off

- Fold diaper below cord to prevent urine contamination

- Teach parents signs of infection requiring medical attention

Feeding Difficulties

Feeding difficulties are common neonatal disorders that can significantly impact growth, development, and parent-infant bonding. Early identification and management of feeding problems are essential aspects of neonatal nursing care.

Common Feeding Issues in Newborns

-

Poor Latch (Breastfeeding)

- Difficulty attaching to breast

- Shallow latch causing nipple pain

- Clicking sounds during feeding

- Insufficient milk transfer

-

Ineffective Sucking

- Weak or disorganized suck

- Inability to maintain rhythmic sucking

- Fatigue during feeding

- Commonly seen in preterm or neurologically impaired infants

-

Regurgitation/Reflux

- Frequent spitting up after feeds

- May be accompanied by irritability

- Arching of back during/after feeding

- Usually physiologic but may be pathologic

-

Anatomical Issues

- Ankyloglossia (tongue-tie)

- Cleft lip/palate

- Micrognathia

Signs of Adequate Feeding in Newborns

Breastfeeding

Audible swallowing

Rhythmic sucking with pauses

Relaxed arms and hands

Breast softening during feed

Satisfied after feeding

Formula Feeding

Steady sucking pattern

Minimal air swallowing

Appropriate volume intake

Completes feeding in 20-30 min

Content after feeding

Output Indicators of Adequate Intake

Urine

- 6+ wet diapers daily after day 4

- Pale yellow color

Stool

- 3+ stools daily by day 4

- Yellow, seedy (breastfed)

- Yellow to tan (formula)

Assessment

| Assessment Parameter | Indicators of Concern | Assessment Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Oral Structure |

|

|

| Feeding Behavior |

|

|

| Growth Parameters |

|

|

| Hydration Status |

|

|

Management Strategies

Breastfeeding Issues

Poor Latch

- Position infant with ear, shoulder, and hip in alignment

- Support breast in “C” hold, away from areola

- Wait for wide mouth opening before bringing baby to breast

- Ensure asymmetric latch with more areola visible above upper lip

- Break suction and reposition if painful

Low Milk Supply

- Increase frequency of breastfeeding (8-12 times/day)

- Ensure proper breast drainage with compression

- Consider supplementary nursing system if needed

- Pump after feeding to increase stimulation

- Assess for medical causes of low supply

Tongue-Tie

- Refer for evaluation by healthcare provider

- May require frenotomy if significantly affecting feeding

- Modify positioning to accommodate restricted tongue movement

Formula Feeding Issues

Bottle Refusal

- Try different nipple shapes or flow rates

- Ensure proper positioning (semi-upright)

- Warm formula to body temperature

- Try paced bottle feeding technique

- Feed when showing early hunger cues

Excessive Gas/Colic

- Burp frequently during and after feeds

- Consider anti-colic bottles

- Hold upright for 20-30 minutes after feeding

- Consider formula change if symptoms persist

- Rule out milk protein sensitivity

Reflux Management

- Smaller, more frequent feeds

- Upright positioning during and after feeds

- Avoid overfeeding

- Consider thickened formula if recommended

- Elevate head of crib/bassinet (if recommended)

Nursing Considerations for Feeding Difficulties:

- Assess every feeding in hospital setting

- Document intake, output, and feeding behaviors

- Provide consistent and evidence-based education to parents

- Recognize cultural practices related to infant feeding

- Refer to lactation consultant for breastfeeding issues

- Connect parents with community resources for ongoing support

- Provide emotional support to parents experiencing feeding challenges

- Follow up with at-risk infants after discharge

FEEDS Mnemonic for Feeding Assessment

F – Frequency and duration of feeding sessions

E – Engagement of infant during feeding

E – Elimination patterns (urine and stool)

D – Discomfort signs during or after feeding

S – Swallowing effectiveness and coordination

Erythema Toxicum Neonatorum

Erythema Toxicum Neonatorum (ETN) is one of the most common benign skin neonatal disorders, affecting approximately 30-70% of full-term newborns. This self-limiting condition requires proper identification to distinguish it from more serious skin disorders.

Etiology

- Exact cause remains unknown

- Theories include:

- Response to skin colonization by normal flora

- Immune system activation against hair follicles

- Transient inflammatory response during skin adaptation

- Histologically shows eosinophilic infiltration

- Not associated with any systemic illness

Clinical Manifestations

- Blotchy, erythematous macules and papules

- Small pustules with surrounding erythema (1-3 mm)

- Typically spares palms and soles

- Most common on trunk, face, extremities

- Appears within 24-72 hours after birth

- Lesions may come and go in different areas

- Resolves spontaneously within 5-7 days

- No associated systemic symptoms

Differential Diagnosis of Newborn Rashes

| Skin Condition | Appearance | Timing | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erythema Toxicum | Yellow-white pustules with erythematous base | 24-72 hours after birth | Face, trunk, extremities (spares palms/soles) |

| Neonatal Acne | Red papules and pustules | 2-4 weeks of age | Face, especially cheeks and forehead |

| Miliaria (Heat Rash) | Small vesicles or papules | Any time | Skin folds, areas covered by clothing |

| Seborrheic Dermatitis | Greasy yellow scales | First 3 months | Scalp, face, behind ears, diaper area |

| Impetigo | Honey-colored crusted lesions | Any time | Face, extremities, areas with skin breakdown |

Note: Unlike more serious conditions, Erythema Toxicum is not associated with systemic symptoms and resolves spontaneously without treatment.

Assessment and Management

Assessment

- Document distribution and appearance of lesions

- Assess for systemic symptoms (should be none)

- Differentiate from other neonatal skin conditions

- Wright stain of pustule contents may show eosinophils (if performed)

- Monitor progression over time

Management

- No treatment required (self-limiting condition)

- Avoid topical medications or ointments on affected areas

- Gentle cleansing with water only

- Avoid harsh soaps or lotions

- Standard newborn skin care

Nursing Considerations:

- Primary role is parental education and reassurance

- Explain benign nature of the condition

- Emphasize that no treatment is necessary

- Teach proper skin care techniques

- Document appearance, distribution, and progression

- Reassure that condition will resolve without scarring

- Differentiate from conditions requiring medical intervention

Clinical Tip:

A simple bedside test can help differentiate Erythema Toxicum from more concerning rashes: If gently stroking the skin adjacent to a lesion produces additional lesions (positive Darier’s sign), further evaluation is needed as this suggests mastocytosis rather than ETN.

Milia

Milia are one of the most common benign skin neonatal disorders, appearing as small, white or yellow papules on a newborn’s face. They result from trapped keratin beneath the epidermis and require no treatment.

Etiology

- Retention of keratin within the dermis

- Trapped keratinized cells in pilosebaceous follicles

- Incomplete separation of epidermis during development

- Formation of tiny epidermal cysts

Clinical Manifestations

- Small (1-2 mm) white or yellowish papules

- Firm, pearly appearance

- Most commonly appear on:

- Nose

- Cheeks

- Chin

- Forehead

- May occasionally appear on upper trunk

- No surrounding erythema or inflammation

- Present at birth or develop in first few weeks

- Usually disappear spontaneously within 1-2 months

Types of Milia

Primary Milia

Most common form seen in newborns

Arise spontaneously from entrapped keratin

Typically resolve within weeks without treatment

No associated systemic conditions

Milia En Plaque

Rare variant not typically seen in newborns

Multiple lesions on an erythematous base

May require dermatology referral

Milia vs. Epstein Pearls

Milia

• On skin surface

• Face, especially nose

Epstein Pearls

• On oral mucosa

• Palate and gums

Both are keratin cysts and resolve spontaneously

Assessment and Management

| Assessment | Management | Parent Education |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Nursing Considerations:

- Focus on parental education and reassurance

- Address parental concerns about appearance

- Emphasize benign nature and self-resolving course

- Strongly discourage picking, squeezing, or applying treatments

- Teach standard newborn skin care practices

- Advise when to seek medical attention (signs of infection)

Important:

Parents should be strongly cautioned against attempting to express milia, as this can lead to skin damage, scarring, and potential infection. Reassure them that these lesions will resolve naturally without intervention.

Mongolian Spots

Mongolian spots (congenital dermal melanocytosis) are common benign birthmarks that present as blue-gray macules on the skin. These represent one of the most common pigmentary neonatal disorders, particularly in infants with darker skin tones.

Etiology

- Result from entrapment of melanocytes in the dermis

- Melanocytes fail to reach the epidermis during embryonic migration

- Genetic factors influence prevalence

- Higher prevalence in certain ethnicities:

- African (90-95%)

- Asian (80-90%)

- Hispanic (70-80%)

- Caucasian (1-10%)

Clinical Manifestations

- Blue-gray or blue-green macules or patches

- Non-blanching

- May vary in size from a few cm to covering large areas

- Most commonly found in:

- Sacral region (most common)

- Buttocks

- Lower back

- Shoulders

- Present at birth

- Usually fade gradually over years

- Most resolve by school age, but some may persist into adulthood

- No associated symptoms

Distinguishing Mongolian Spots from Bruising

Clinical Significance in Child Protection

Mongolian spots can be mistaken for bruising, potentially leading to unwarranted child abuse investigations. Careful documentation is essential for preventing such misunderstandings.

| Feature | Mongolian Spots | Bruises |

|---|---|---|

| Present at birth | Yes | No (except birth trauma) |

| Color change | Stable over weeks/months | Changes over days |

| Location | Sacrum, buttocks, shoulders | Variable, often on bony prominences |

| Borders | Diffuse, irregular | Often more defined |

| Tenderness | None | Often present |

| Texture | Same as surrounding skin | May be raised or swollen |

Assessment and Management

Assessment

- Document location, size, color, and appearance

- Photograph lesions (with parental consent)

- Include a measuring device for scale

- Maintain in medical record

- Distinguish from other skin lesions or bruising

- Assess for other birthmarks or skin findings

- Comprehensive skin assessment

Management

- No medical treatment required

- Maintain normal skin care

- Provide thorough documentation in medical record

- Provide a letter to parents describing the condition

- Consider referral if spots are:

- Unusually extensive

- In atypical locations (face, arms)

- Associated with other congenital anomalies

Nursing Considerations:

- Thorough documentation is essential for preventing misunderstandings about potential abuse

- Provide culturally sensitive education about the benign nature of these birthmarks

- Emphasize the natural resolution over time

- Provide a written description for parents to share with future healthcare providers

- Include information about Mongolian spots in discharge teaching

- Address any parental concerns about cosmetic appearance

Documentation Tip:

For effective documentation of Mongolian spots, use the “DESCRIBE” approach: Document size, color, region, irregular borders, birth-presence, expected resolution, and provide education to parents. This comprehensive documentation helps prevent misidentification as bruising in future healthcare encounters.

Cephalohematoma

Cephalohematoma is a common birth-related neonatal disorder characterized by a collection of blood between the periosteum and the skull bone. It’s important for nursing professionals to understand its characteristics, progression, and management to provide appropriate care and parental education.

Etiology

- Results from traumatic birth process

- Caused by rupture of blood vessels between skull bone and periosteum

- Risk factors include:

- Prolonged labor

- Vacuum-assisted delivery

- Forceps delivery

- Large fetal head circumference

- Primiparity

- Cephalopelvic disproportion

Clinical Manifestations

- Soft, fluctuant swelling on the scalp

- Does not cross suture lines (limited by periosteal attachment at sutures)

- Usually unilateral, commonly over parietal bone

- May not be apparent immediately at birth

- Often becomes more prominent in first few days

- No skin discoloration initially

- No tenderness on palpation

- Usually resolves within 2 weeks to 3 months

- Possible calcification with prolonged cases

Cephalohematoma vs. Caput Succedaneum

| Feature | Cephalohematoma | Caput Succedaneum |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Blood between periosteum and skull bone | Edema of scalp tissue |

| Crosses suture lines | No | Yes |

| Onset | May appear hours after birth | Present immediately at birth |

| Duration | Weeks to months | Days (usually 3-7 days) |

| Consistency | Fluctuant, doesn’t pit on pressure | Soft, pits on pressure |

| Complications | Jaundice, infection (rare), calcification | Rarely any complications |

Cross-Section Comparison

Cephalohematoma

Blood confined within suture lines

Caput Succedaneum

Edema crossing suture lines

Assessment and Management

| Assessment | Management | Complications to Monitor |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Monitoring for Complications

Hyperbilirubinemia

- Monitor for jaundice as blood reabsorbs

- Serial bilirubin levels if jaundice present

- Encourage frequent feeding to promote excretion

- Assess for signs of dehydration

Infection

- Monitor for:

- Increased swelling

- Redness or warmth

- Fever

- Increased irritability

- Maintain scalp hygiene

- Avoid pressure on affected area

Nursing Considerations:

- Document birth history and risk factors

- Measure and document size of cephalohematoma

- Monitor for signs of increased intracranial pressure

- Position infant to avoid pressure on affected area

- Educate parents about:

- Normal resolution timeline (weeks to months)

- Possible temporary “bump” appearance as edges reabsorb first

- Signs of infection requiring medical attention

- Jaundice monitoring

- Provide reassurance about long-term outcomes

Warning:

Never attempt to aspirate or drain a cephalohematoma, as this introduces risk of infection and is not medically indicated. The body will naturally reabsorb the blood over time.

Caput Succedaneum

Caput succedaneum is a common, benign neonatal disorder characterized by diffuse swelling of the scalp due to pressure during delivery. Unlike cephalohematoma, it involves soft tissue edema rather than a collection of blood and typically resolves within days without intervention.

Etiology

- Results from pressure on fetal head during labor

- Occurs when head is pressed against cervix for extended periods

- Risk factors include:

- Prolonged labor

- Prolonged rupture of membranes

- Vacuum-assisted delivery

- Nulliparity

- Cephalopelvic disproportion

- Can occur with both vaginal and cesarean deliveries

Clinical Manifestations

- Soft, diffuse swelling of scalp tissue

- Crosses suture lines (key distinguishing feature)

- Present immediately at birth

- May have associated ecchymosis or purpura

- Pits on pressure (due to edematous nature)

- Usually resolves within 3-7 days

- Typically does not cause pain or discomfort

- No neurological symptoms

Key Characteristics of Caput Succedaneum

Anatomical Involvement

Caput succedaneum involves only the superficial tissues:

Skin

Subcutaneous tissue

Connective tissue (fascia)

Does not involve periosteum or bone

Distributional Pattern

Crosses suture lines

Diffuse swelling not confined by suture lines

Resolution Timeline

Typically resolves completely within one week

Assessment and Management

| Assessment | Management | Parent Education |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Nursing Considerations:

- Document characteristics of caput succedaneum in initial assessment

- Differentiate from other scalp conditions (cephalohematoma, subgaleal hemorrhage)

- Monitor resolution during hospital stay

- Provide anticipatory guidance to parents

- Address parental concerns about appearance

- Include in discharge teaching with expected timeline

- Teach parents normal newborn scalp care

- Advise when to seek medical attention (persistence beyond 7 days)

Clinical Pearl:

While caput succedaneum itself is benign, it can occasionally mask an underlying subgaleal hemorrhage, which is a medical emergency. Be alert for signs such as increasing head circumference, progressive scalp swelling extending beyond normal caput distribution, pallor, or signs of hypovolemic shock, which would warrant immediate medical attention.

Prevention and Best Practices

While many neonatal disorders are transient and benign, implementing evidence-based preventive strategies and best practices can significantly reduce their incidence and severity. Nursing professionals play a crucial role in educating parents and implementing these preventative measures.

PREVENT Mnemonic for Neonatal Disorders

P – Proper skin care with gentle cleansers

R – Regular feedings to prevent hyperbilirubinemia

E – Early identification and management

V – Vigilant monitoring of skin changes

E – Education of parents on normal variants

N – Nurture bonding despite cosmetic concerns

T – Thorough documentation of findings

Best Practices for Common Neonatal Disorders

| Disorder | Preventive Strategies | Global Best Practices |

|---|---|---|

| Physiological Jaundice |

|