Malaria: Community Health Nursing Perspectives

Community Health Nurse Educating on Malaria Prevention

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Epidemiology of Malaria

- Malaria Vectors and Transmission

- Malaria Parasite Life Cycle

- Clinical Manifestations and Complications

- Prevention and Control Measures

- Screening and Diagnosis

- Primary Management

- Referral Criteria

- Follow-up Care

- Role of Community Health Nurses

- Community Education and Intervention

- References and Resources

Introduction

Malaria remains one of the most significant vector-borne diseases globally, affecting millions of people each year, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions. Community health nurses play a crucial role in malaria prevention, control, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up care. This comprehensive guide explores malaria from a community health nursing perspective, providing essential knowledge and practical approaches for effective malaria prevention and management in community settings.

What is Malaria?

Malaria is a life-threatening parasitic disease caused by Plasmodium parasites, transmitted to humans through the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. Five parasite species cause malaria in humans, with Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax posing the greatest threat. Community-based malaria prevention programs are essential for reducing disease burden, especially in endemic areas.

Epidemiology of Malaria

Understanding the epidemiology of malaria is vital for community health nurses to implement effective prevention and control strategies. Malaria prevention in communities requires knowledge of local epidemiological patterns to tailor interventions appropriately.

Global Burden

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there were an estimated 249 million malaria cases worldwide in 2022, with the African region carrying approximately 94% of cases and 95% of deaths. Children under 5 years of age are particularly vulnerable, accounting for about 80% of all malaria deaths in Africa.

Risk Factors

Several factors influence malaria transmission and vulnerability within communities:

- Geography and climate (tropical and subtropical regions)

- Socioeconomic conditions

- Housing quality and proximity to breeding sites

- Age (young children and pregnant women are at higher risk)

- Immunity status

- Access to healthcare and malaria prevention services

Essential Malaria Prevention Methods

Transmission Dynamics

Malaria prevention at the community level requires understanding local transmission patterns:

- Stable transmission: Year-round transmission with little seasonal fluctuation

- Unstable transmission: Marked seasonal patterns with potential for epidemics

- Epidemic-prone areas: Areas with irregular transmission but potential for outbreaks

| Plasmodium Species | Geographic Distribution | Clinical Features | Relapse Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. falciparum | Tropical Africa, Asia, Latin America | Most severe form; can cause cerebral malaria | No, but can persist as chronic infection |

| P. vivax | Asia, Latin America, some parts of Africa | Less severe, but can cause recurrent malaria | Yes, can relapse months to years later |

| P. ovale | Mainly West Africa | Similar to P. vivax | Yes, can relapse |

| P. malariae | Worldwide in tropical regions | Mild symptoms, can persist for decades | No relapses, but long-term persistence |

| P. knowlesi | Southeast Asia | Can rapidly progress to severe disease | No |

Key Epidemiological Insight for Community Health Nurses:

Understanding the local malaria epidemiology allows for targeted malaria prevention interventions, efficient resource allocation, and appropriate timing of preventive measures, particularly in areas with seasonal transmission patterns.

Malaria Vectors and Transmission

Community-based malaria prevention requires a thorough understanding of the vectors responsible for transmission and their behavior patterns.

Anopheles Mosquitoes

Female Anopheles mosquitoes are the exclusive vectors of human malaria. Of approximately 430 Anopheles species, only about 30-40 are important malaria vectors. Key characteristics that affect malaria prevention strategies include:

Feeding Behavior

- Primarily feed during evening and night (dusk to dawn)

- Some species prefer to feed indoors (endophagic)

- Others prefer outdoor feeding (exophagic)

Resting Behavior

- Indoor resting (endophilic) – susceptible to indoor spraying

- Outdoor resting (exophilic) – require different control measures

Breeding Sites

Anopheles mosquitoes breed in water bodies, but preferences vary by species:

- Clean, sunlit water bodies (ponds, rice fields)

- Small, temporary water collections (puddles, hoof prints)

- Forest streams (some species)

- Brackish water (certain species)

Understanding local vector breeding preferences is crucial for targeted malaria prevention through environmental management.

Transmission Cycle

The malaria transmission cycle involves:

- An infected female Anopheles mosquito bites a human

- Parasites enter the human bloodstream

- The parasite develops in the human host

- A different mosquito bites the infected person

- The mosquito becomes infected and can transmit to others

Important for Community Nurses:

Vector control is one of the most effective malaria prevention strategies. Community health nurses should educate communities about the importance of eliminating mosquito breeding sites and using personal protection measures, particularly during peak biting hours.

Malaria Parasite Life Cycle

Understanding the malaria parasite life cycle is essential for effective malaria prevention, diagnosis, and treatment in community settings.

Life Cycle of the Malaria Parasite

The malaria parasite life cycle involves two hosts: the human and the mosquito. Each stage presents different opportunities for malaria prevention and intervention:

1 Human Liver Stage (Exo-erythrocytic)

When an infected female Anopheles mosquito bites a human, it injects sporozoites into the bloodstream. These sporozoites travel to the liver and invade liver cells where they multiply and develop into schizonts. This stage is clinically silent, with no symptoms of malaria.

Duration: 7-30 days, depending on Plasmodium species

Prevention opportunity: Chemoprophylaxis can target this stage

2 Blood Stage (Erythrocytic)

Merozoites released from the liver invade red blood cells, where they multiply, rupture the cells, and release more merozoites to infect other red blood cells. This cycle causes the characteristic symptoms of malaria.

Duration: 48-72 hours depending on species

Clinical impact: This stage causes fever, chills, and other malaria symptoms

Treatment target: Most antimalarial drugs target this stage

3 Sexual Stage (Gametocyte Production)

Some parasites develop into male and female gametocytes within red blood cells, which can be ingested by mosquitoes during a blood meal.

Prevention opportunity: Gametocidal drugs can prevent transmission

4 Mosquito Stage (Sporogonic)

In the mosquito’s gut, male and female gametocytes mature, fertilize, and develop through several stages, eventually producing sporozoites that migrate to the mosquito’s salivary glands, ready to infect another human.

Duration: 10-18 days

Prevention opportunity: Vector control prevents this stage

Community Health Nurse Perspective:

Understanding the malaria life cycle helps in explaining to community members why certain malaria prevention measures are effective at specific times, such as using bed nets during nighttime mosquito feeding periods and the importance of completing the full course of treatment to eliminate all parasites.

Special Consideration: Hypnozoites

P. vivax and P. ovale can form dormant liver stages (hypnozoites) that can activate weeks to months later, causing relapse. This is why radical cure with primaquine is necessary for these species to prevent recurrences and maintain effective malaria prevention.

Clinical Manifestations and Complications

Community health nurses must be able to recognize the clinical manifestations of malaria for early detection and prompt treatment, which are key aspects of malaria prevention and control at the community level.

Incubation Period

The time between infection and symptom onset varies by species:

- P. falciparum: 9-14 days

- P. vivax and P. ovale: 12-18 days

- P. malariae: 18-40 days

- P. knowlesi: As short as 24 hours

Classic Malaria Symptoms

The classic malaria paroxysm consists of three stages:

Cold Stage

Intense feelings of cold and shivering lasting 15-60 minutes

Hot Stage

High fever (often >40°C), headaches, vomiting lasting 2-6 hours

Sweating Stage

Profuse sweating, temperature normalization, fatigue lasting 2-4 hours

Other common symptoms include:

- Headache and body aches

- Fatigue

- Nausea and vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Diarrhea

- Cough

- Anemia

- Jaundice (in some cases)

Mnemonic: “MALARIA” for Complications

M – Mental changes (cerebral malaria)

A – Anemia (severe)

L – Lactic acidosis

A – Acute respiratory distress syndrome

R – Renal failure

I – Icterus (jaundice)

A – Algid malaria (circulatory collapse)

Severe Malaria

Severe malaria is a medical emergency, most commonly caused by P. falciparum. Community health nurses should recognize these danger signs for immediate referral:

Danger Signs Requiring Immediate Referral:

- Impaired consciousness or coma

- Severe anemia (hemoglobin <5 g/dL)

- Respiratory distress

- Multiple convulsions

- Circulatory collapse or shock

- Pulmonary edema

- Abnormal bleeding

- Jaundice

- Hemoglobinuria

- Hypoglycemia

- Renal impairment

Special Populations

Pregnant Women

At higher risk for severe malaria, placental malaria, anemia, low birth weight, premature delivery, and maternal death. Malaria prevention is especially critical for this population.

Children Under 5

More likely to develop severe manifestations rapidly. May present with atypical symptoms including cough, lethargy, and poor feeding. Malaria prevention programs often target this vulnerable group.

Community Health Nursing Implications:

Early recognition of malaria symptoms and prompt treatment are crucial components of community-based malaria prevention efforts. Community health nurses should educate community members on recognizing symptoms and seeking immediate care, which is essential for preventing severe complications and reducing transmission.

Prevention and Control Measures

Malaria prevention is a cornerstone responsibility for community health nurses working in endemic areas. Effective prevention strategies can significantly reduce the burden of malaria in communities.

Comprehensive Malaria Prevention Approaches

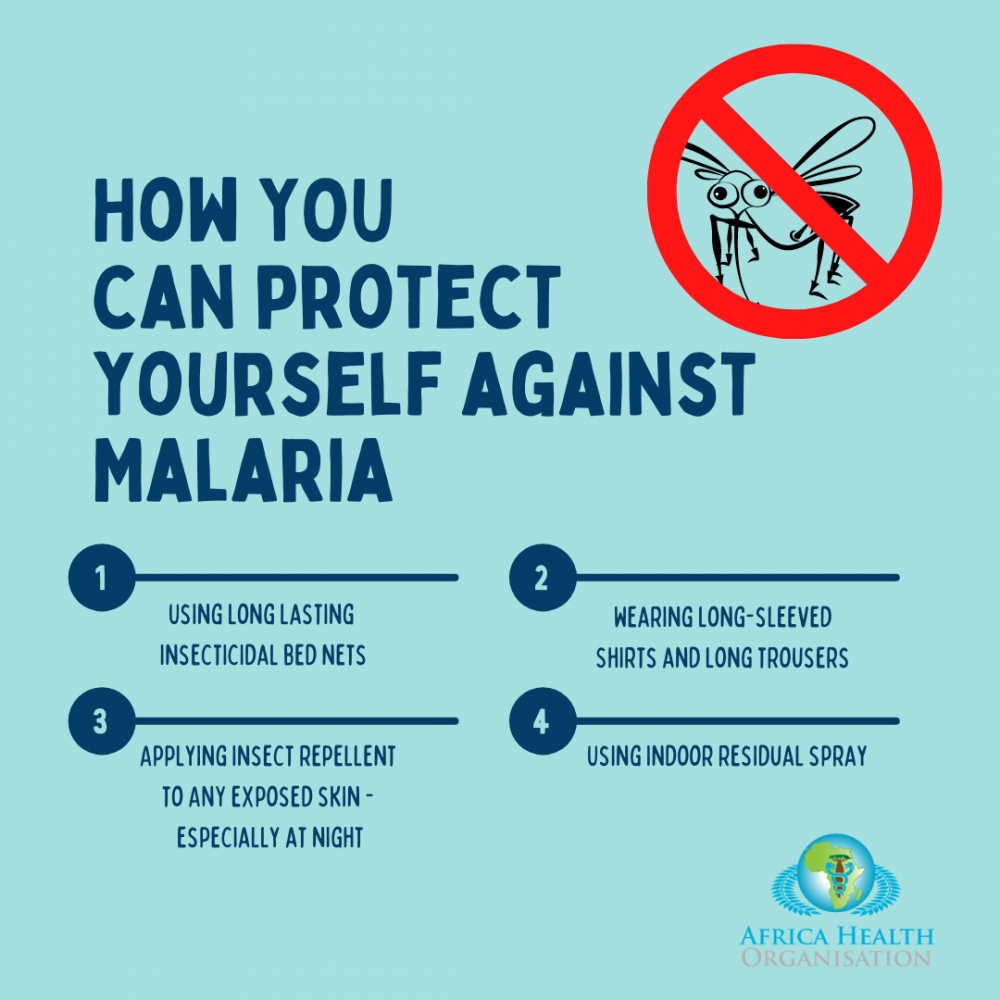

Vector Control

Vector control is the primary method of reducing malaria transmission at the community level. Community health nurses play key roles in implementing and promoting these strategies:

Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs)

- Long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) can reduce malaria transmission by 50%

- Effective for 2-3 years without retreatment

- Community distribution ensures coverage

- Proper use education is essential

Nursing role: Distribution, education on proper use and maintenance, follow-up to ensure consistent usage

Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS)

- Application of insecticide on interior walls and ceilings

- Kills mosquitoes that rest on these surfaces

- Provides protection for 3-6 months

- Requires proper planning and community acceptance

Nursing role: Community education, coordination of IRS campaigns, monitoring for side effects

Larval Source Management

Reducing mosquito breeding sites through:

- Environmental modification (draining, filling)

- Larviciding (biological or chemical agents)

- Community clean-up campaigns

Community health nurses can organize and lead community participation in these activities, which are essential components of malaria prevention programs.

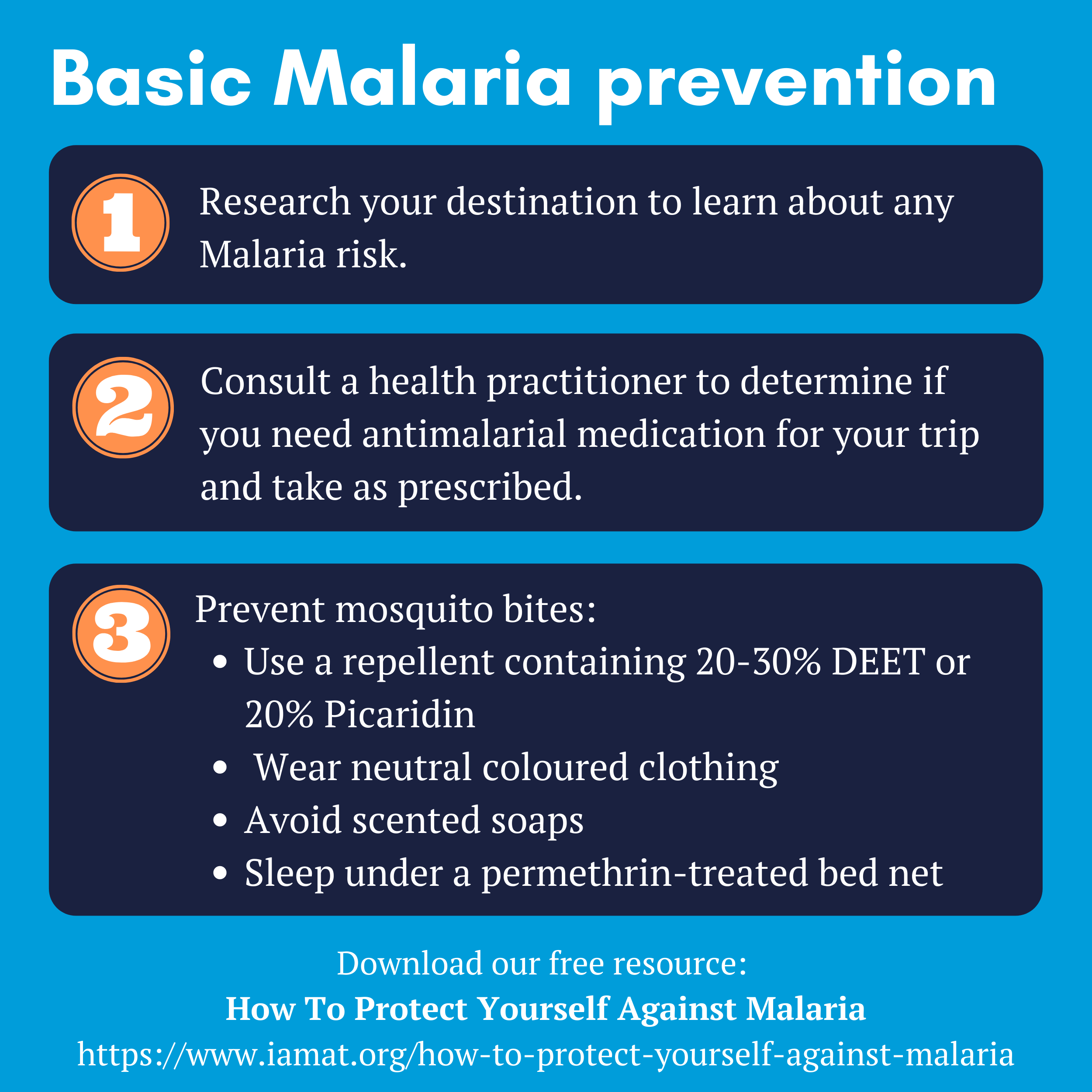

Personal Protection Measures

Community health nurses should educate individuals about personal protective measures as part of malaria prevention:

Physical Barriers

- Window and door screens

- Protective clothing

- Bed nets (even untreated)

Repellents

- DEET-based repellents

- Picaridin

- IR3535

- Natural repellents

Behavioral

- Avoiding outdoor activities at peak biting times

- Using fans to disrupt mosquito flight

- Sleeping in screened or air-conditioned rooms

Chemoprophylaxis and Preventive Therapy

Medications used to prevent malaria are important in specific settings and populations:

Mnemonic: “MACDOT” for Malaria Chemoprophylaxis

M – Mefloquine

A – Atovaquone-proguanil

C – Chloroquine (in sensitive areas)

D – Doxycycline

O – Once weekly (some regimens)

T – Take before, during, and after exposure

Special Preventive Therapies

| Strategy | Target Population | Medication | Nursing Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intermittent Preventive Treatment in Pregnancy (IPTp) | Pregnant women in endemic areas | Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) | Administration during antenatal care, education on importance |

| Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention (SMC) | Children under 5 in seasonal transmission areas | SP + amodiaquine | Organize distribution, monitor coverage and side effects |

| Intermittent Preventive Treatment in infants (IPTi) | Infants | SP | Administration during routine immunization visits |

| Mass Drug Administration (MDA) | Entire communities in specific contexts | Various antimalarials | Campaign organization, community mobilization |

Environmental Management

Community health nurses should advocate for and organize environmental interventions as part of comprehensive malaria prevention:

- Removal of standing water

- Proper waste disposal

- Clearing vegetation around homes

- Improving house design and materials

- Community clean-up campaigns

Community Approach to Prevention:

Effective malaria prevention requires a combination of approaches tailored to local conditions. Community health nurses are ideally positioned to coordinate these efforts, educate communities, and ensure sustained implementation over time.

Screening and Diagnosis

Accurate and timely diagnosis is crucial for effective malaria prevention and control. Community health nurses need to understand various diagnostic methods and their applications in community settings.

When to Suspect Malaria

Any fever or history of fever in a malaria-endemic area should be considered malaria until proven otherwise, especially in:

- Children under 5 years

- Pregnant women

- Travelers from non-endemic areas

- People with compromised immunity

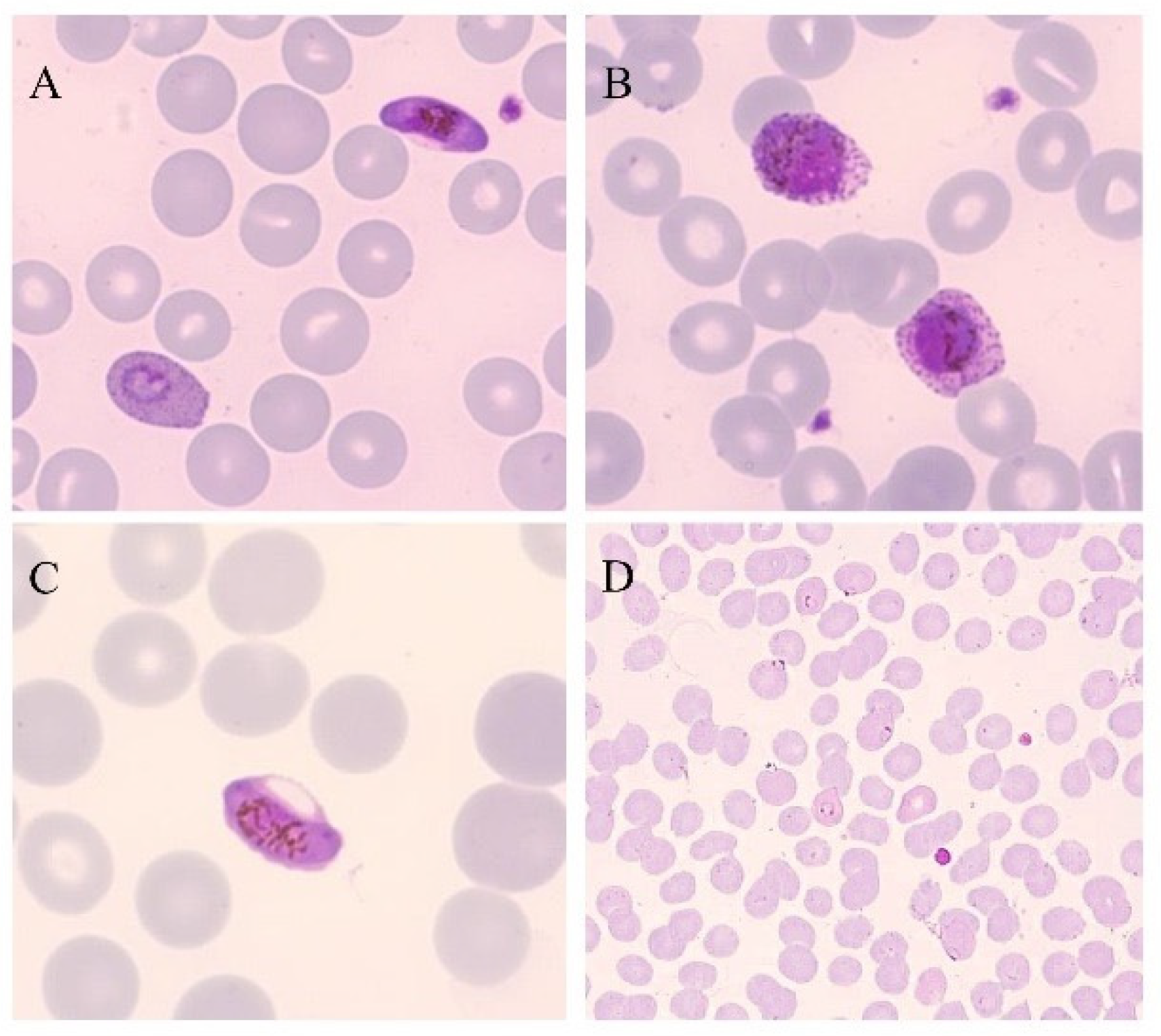

Microscopy: The Gold Standard

Malaria Parasite in Blood Smear (CDC)

Microscopic examination remains the gold standard for diagnosing malaria:

Thick Blood Smear

- Used for detecting presence of parasites

- Higher sensitivity for initial detection

- Can detect as few as 4-20 parasites/μL

Thin Blood Smear

- Used for species identification

- Allows examination of parasite morphology

- Permits calculation of parasitemia percentage

Limitations in community settings include:

- Requires trained microscopists

- Needs good quality microscopes and reagents

- Time-consuming

- Quality may vary with microscopist experience

Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs)

RDTs have revolutionized malaria diagnosis in community settings and are a crucial tool for malaria prevention programs:

Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Test Procedure

How RDTs Work

RDTs detect malaria antigens in blood using immunochromatographic principles:

- HRP2 (Histidine-Rich Protein 2) – specific to P. falciparum

- pLDH (Plasmodium Lactate Dehydrogenase) – can be specific or pan-specific

- Aldolase – pan-specific (detects all species)

Advantages for Community Settings

- Rapid results (15-20 minutes)

- Simple to perform with minimal training

- No electricity or specialized equipment needed

- Can be deployed at community level by CHWs

- Improves access to diagnosis in remote areas

Limitations

- Cannot quantify parasitemia

- May remain positive after successful treatment (especially HRP2-based tests)

- Some P. falciparum strains have HRP2 deletions causing false negatives

- Less sensitive at low parasite densities

- Limited shelf life, especially in hot conditions

RDT Procedure for Community Health Nurses

- Wear gloves and prepare all materials

- Clean finger with alcohol swab and allow to dry

- Prick finger with sterile lancet

- Collect blood sample with provided device

- Apply blood to test area

- Add buffer solution

- Wait specified time (usually 15-20 minutes)

- Read and interpret results according to manufacturer instructions

- Dispose of materials safely

- Record results and take appropriate action

Other Diagnostic Methods

While not typically available at the community level, community health nurses should be aware of other diagnostic methods that may be used at referral facilities:

- PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction): Highly sensitive molecular method, used in research, surveillance, and quality control

- Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP): Molecular method that can be used in field settings with minimal equipment

- Fluorescence microscopy: Enhanced sensitivity compared to conventional microscopy

- Serology: Detects antibodies, useful for epidemiological studies but not for diagnosis of acute infection

Community Health Nursing Implications:

Community health nurses should follow the “test before treat” principle, ensuring that all suspected malaria cases are confirmed with either microscopy or RDTs before treatment. This approach improves patient care, reduces unnecessary antimalarial use, and strengthens malaria surveillance—all vital components of malaria prevention programs.

Primary Management

Prompt and effective treatment is a critical component of malaria prevention and control at the community level. Community health nurses play essential roles in ensuring appropriate treatment is provided.

General Principles of Malaria Treatment

- Confirm diagnosis before treatment when possible

- Treat promptly – within 24-48 hours of symptom onset

- Use appropriate medications based on:

- Plasmodium species

- Local resistance patterns

- Severity of illness

- Patient characteristics (age, pregnancy, comorbidities)

- Ensure complete treatment course is taken

- Address symptoms and complications

- Follow up to confirm resolution

Treatment of Uncomplicated Malaria

For uncomplicated malaria, community health nurses should be familiar with first-line treatments according to local guidelines:

| Parasite | Recommended Treatment | Duration | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. falciparum | Artemisinin-based Combination Therapy (ACT) | 3 days | Choice of ACT depends on local guidelines (e.g., artemether-lumefantrine, artesunate-amodiaquine) |

| P. vivax | Chloroquine (in sensitive areas) + Primaquine | Chloroquine: 3 days Primaquine: 14 days |

G6PD testing required before primaquine for radical cure |

| P. ovale | Chloroquine + Primaquine | Chloroquine: 3 days Primaquine: 14 days |

G6PD testing required before primaquine |

| P. malariae | Chloroquine | 3 days | Generally responsive to chloroquine |

| P. knowlesi | ACT or Chloroquine | 3 days | Can rapidly progress to severe disease |

| Unknown species | ACT | 3 days | Default treatment in most endemic areas |

Key Points on ACTs

Artemisinin-based Combination Therapies (ACTs) are the WHO-recommended first-line treatments for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria. Common ACTs include:

- Artemether-lumefantrine

- Artesunate-amodiaquine

- Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine

- Artesunate-mefloquine

- Artesunate-sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine

Pre-Referral Treatment for Severe Malaria

When severe malaria is suspected in a community setting, community health nurses should administer pre-referral treatment while arranging urgent transfer to a facility:

Pre-Referral Options:

- Intramuscular artesunate (preferred)

- Intramuscular artemether

- Intramuscular quinine

- Rectal artesunate (especially for children under 6 years)

Important: After pre-referral treatment, immediate transfer to a facility with capabilities for managing severe malaria is essential.

Supportive Care in Community Settings

In addition to antimalarial treatment, community health nurses should provide supportive care:

- Fever management with antipyretics (e.g., paracetamol)

- Adequate hydration

- Monitoring for treatment response and complications

- Nutrition support

- Education on completing the full treatment course

Community Health Nursing Implementation:

Community health nurses should ensure appropriate treatment is started promptly, educate patients on medication adherence, and follow up to confirm treatment success. This approach not only improves individual outcomes but also contributes to malaria prevention by reducing the parasite reservoir in the community.

Referral Criteria

Community health nurses must recognize when patients require referral to higher-level facilities, which is a critical aspect of community-based malaria prevention and management.

Indications for Urgent Referral

Refer Immediately If:

- Any signs of severe malaria:

- Impaired consciousness or coma

- Severe anemia

- Respiratory distress

- Multiple convulsions

- Circulatory collapse or shock

- Jaundice

- Abnormal bleeding

- Hemoglobinuria

- Unable to take oral medications

- Persistent vomiting

- Pregnant women with malaria

- Children under 6 months with malaria

- Elderly patients (>65 years) with malaria

- Patients with comorbidities (HIV, diabetes, etc.)

- Treatment failure

Referral Process

- Recognize need for referral based on danger signs or other criteria

- Administer pre-referral treatment if appropriate

- Stabilize patient as much as possible

- Complete referral form with relevant clinical information

- Arrange transportation (emergency if necessary)

- Communicate with referral facility if possible

- Advise family members about the referral reasons and process

- Follow up to confirm arrival at referral facility

Referral Documentation

Comprehensive documentation should accompany referred patients:

- Patient demographics

- Presenting symptoms and duration

- Vital signs and physical findings

- Diagnostic test results (RDT or microscopy)

- Treatments given (dose, route, time)

- Reason for referral

- Pre-referral interventions

- Contact information for feedback

Importance for Malaria Prevention and Control:

Effective referral systems are essential for reducing malaria mortality. Community health nurses serve as a critical link in the healthcare continuum, ensuring patients with potentially severe disease receive appropriate care quickly. This contributes to overall malaria prevention goals by reducing case fatality and providing data for surveillance systems.

Follow-up Care

Follow-up care is an essential component of malaria prevention and management in community settings. Community health nurses play a pivotal role in monitoring treatment outcomes and preventing recurrences.

Follow-up Schedule

Recommended follow-up timeline for uncomplicated malaria:

Day 3

- Assess clinical improvement

- Check treatment adherence

- Monitor for any danger signs

- Repeat RDT/microscopy if symptoms persist

Day 7

- Confirm resolution of symptoms

- Check for complete treatment adherence

- Assess for complications

- Reinforce prevention measures

Day 14-28

- Final follow-up to detect early recrudescence

- Assess overall recovery

- Reinforce malaria prevention measures

- Special attention for P. vivax/ovale cases

Follow-up Activities

During follow-up visits, community health nurses should:

- Assess treatment response:

- Resolution of fever and other symptoms

- Improvement in general condition

- Return to normal activities

- Check for treatment adherence:

- Verify complete course taken as prescribed

- Address any issues with medication side effects

- Monitor for complications:

- Anemia

- Persistent symptoms

- Development of any severe manifestations

- Reinforce prevention measures:

- Proper use of bed nets

- Environmental management

- Recognition of symptoms for early treatment

Management of Treatment Failure

Treatment failure may be suspected if:

- Symptoms persist or worsen after 3 days of treatment

- Fever returns within 28 days of initial treatment

- Parasitemia persists or returns

Actions for suspected treatment failure:

- Confirm with microscopy if available

- Evaluate adherence to initial treatment

- Administer second-line treatment according to national guidelines

- Consider referral if necessary

- Report as a sentinel event for malaria surveillance

Special Considerations for P. vivax and P. ovale

Due to the risk of relapse from hypnozoites:

- Extended follow-up for up to 1 year

- Ensure completion of primaquine course (after G6PD testing)

- Educate about potential for relapse and need to seek care promptly

- Consider directly observed therapy for primaquine in some settings

Community Health Nursing Implications:

Systematic follow-up is essential for ensuring treatment effectiveness, detecting complications early, and reinforcing malaria prevention behaviors. Community health nurses should develop and implement structured follow-up protocols within their malaria prevention and control programs.

Role of Community Health Nurses

Community health nurses serve as frontline healthcare providers in malaria endemic areas, with comprehensive responsibilities spanning prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up care. Their multifaceted role is crucial for effective malaria prevention at the community level.

Clinical Roles

- Screening for malaria cases in the community

- Performing and interpreting RDTs

- Collecting blood smears when necessary

- Administering appropriate treatment for uncomplicated cases

- Pre-referral management of severe cases

- Monitoring treatment response

- Managing mild adverse effects

- Ensuring treatment adherence

- Providing supportive care

Prevention Roles

- Distribution and education on proper use of ITNs

- Coordination of IRS campaigns

- Organizing community environmental management activities

- Implementing chemoprevention programs (IPTp, SMC)

- Promoting personal protection measures

- Conducting household assessments for malaria risk

- Facilitating community clean-up activities

- Coordinating with other sectors (education, agriculture, etc.)

Educational Roles

- Conducting health education sessions on malaria

- Training community health workers

- Developing culturally appropriate educational materials

- Organizing community awareness campaigns

- School-based education programs

- Peer education initiatives

- Media engagement for public awareness

- Education on recognizing malaria symptoms and seeking care

Administrative Roles

- Case notification and reporting

- Maintaining malaria registers and records

- Stock management of diagnostics and antimalarials

- Planning and evaluating malaria control activities

- Coordinating with malaria control programs

- Quality assurance of diagnostic and treatment services

- Supervision of community health workers

- Data collection for monitoring and evaluation

Collaboration with Other Stakeholders

For effective malaria prevention, community health nurses must collaborate with:

- Community health workers

- Traditional birth attendants

- Community leaders and influencers

- Schools and teachers

- Religious institutions

- Local government structures

- Other health facilities and referral centers

- Agricultural extension workers

- NGOs and international organizations

Case Study: Nurse-led Community Malaria Prevention

In rural Nigeria, community health nurses implemented a comprehensive malaria prevention program that included:

- Training of community health workers to conduct household visits

- Community-based distribution of ITNs with demonstrations on proper use

- Regular health education sessions at community gathering points

- Establishment of malaria testing and treatment points within communities

- Formation of community environmental management teams

This integrated approach resulted in a 45% reduction in malaria cases over two years, demonstrating the effectiveness of nurse-led community-based malaria prevention initiatives.

Core Competencies for Community Health Nurses in Malaria Prevention:

To effectively fulfill their roles in malaria prevention and control, community health nurses require:

- Strong clinical skills in malaria diagnosis and management

- Knowledge of local malaria epidemiology and transmission patterns

- Effective communication and health education capabilities

- Community engagement and mobilization skills

- Program planning and evaluation abilities

- Data collection and basic analysis competencies

- Supervisory and leadership qualities

Community Education and Intervention

Community education and engagement are central to successful malaria prevention and control. Community health nurses must employ effective strategies to foster community participation and ownership of malaria prevention initiatives.

Key Educational Topics

Comprehensive community education for malaria prevention should cover:

Malaria Basics

- Cause and transmission

- Signs and symptoms

- High-risk groups

- Local epidemiology

- Malaria myths and misconceptions

Prevention Methods

- Proper use of ITNs

- Environmental management

- Personal protection measures

- Chemoprevention (for target groups)

- House improvement techniques

Care-Seeking

- When to seek care

- Where to access services

- Importance of testing before treatment

- Treatment adherence

- Danger signs requiring immediate attention

Effective Educational Strategies

Community health nurses should utilize diverse strategies for malaria prevention education:

- Interactive group sessions: Participatory learning with discussions and Q&A

- Demonstration and practice: Hands-on learning for skills like net installation

- Visual aids: Posters, flip charts, and pictorial guides

- Role plays and dramas: Illustrate key messages through performances

- Storytelling: Using local narratives to convey malaria prevention messages

- Peer education: Training community members to educate others

- Home visits: Personalized education and assessment

- Media: Radio programs, mobile messages, community announcements

- School-based programs: Engaging children as change agents

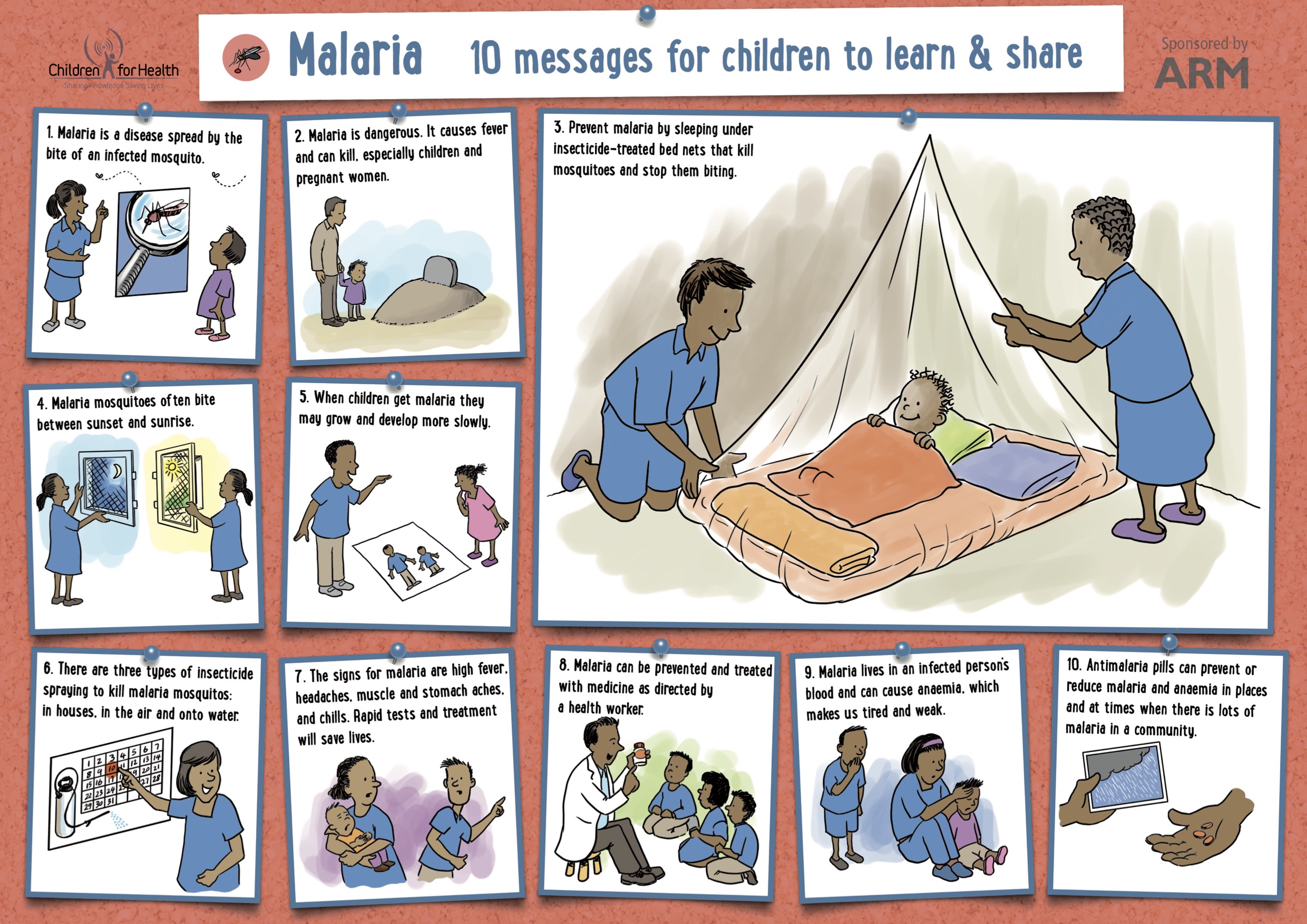

Effective Community Education Materials for Malaria Prevention (Source: Children for Health)

Community Mobilization for Malaria Prevention

Beyond education, community health nurses should facilitate active community participation in malaria prevention activities:

Community Mobilization Process

- Assessment: Identify local malaria burden, risk factors, and community resources

- Engagement: Involve community leaders and influential members

- Awareness: Create community-wide understanding of malaria issues

- Planning: Develop community action plans with local input

- Implementation: Carry out community-led malaria prevention activities

- Monitoring: Track progress and adjust approaches as needed

- Sustainability: Build local capacity for ongoing activities

Community-Led Activities for Malaria Prevention

Examples of community-led malaria prevention initiatives that nurses can facilitate:

- Community clean-up campaigns: Regular removal of breeding sites

- Net distribution committees: Local oversight of ITN distribution

- Mosquito scouts: Volunteers who identify and map breeding sites

- Malaria support groups: Peer education and support networks

- Community surveillance: Volunteers who help identify cases

- Environmental management teams: Ongoing vector habitat reduction

- School malaria clubs: Student-led awareness and prevention

Addressing Social and Cultural Factors

Community health nurses must consider social and cultural dimensions that influence malaria prevention:

- Local beliefs about causes and treatment of fever

- Traditional practices related to mosquito avoidance

- Gender roles in health decision-making

- Economic barriers to prevention measures

- Housing and environmental conditions

- Community power structures and decision processes

Best Practices for Community-Based Malaria Prevention:

Evidence shows that the most effective community-based malaria prevention programs:

- Are tailored to local context and needs

- Use multiple complementary approaches

- Engage a wide range of community stakeholders

- Build on existing community structures

- Provide ongoing support rather than one-time interventions

- Include monitoring and feedback mechanisms

- Strengthen local capacity for sustainable action

References and Resources

These evidence-based resources can support community health nurses in their malaria prevention and control efforts:

Guidelines and Protocols

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2024). Guidelines for malaria. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/guidelines-for-malaria

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2024). Malaria – Diagnosis & treatment. https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/diagnosis_treatment/index.html

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2023). Malaria vector control. https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/prevention/vector-control

Training Resources

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2019). MALARIA: A manual for community health workers. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/41875/1/9241544910_eng.pdf

- The Carter Center. The Life Cycle of Malaria. https://www.cartercenter.org/resources/pdfs/news/health_publications/malaria/malaria-life-cycle-chart.pdf

- Medicines for Malaria Venture. Lifecycle of the malaria parasite. https://www.mmv.org/malaria/about-malaria/lifecycle-malaria-parasite

Community Engagement Resources

- Owusu-Addo, E., & Owusu-Addo, S. B. (2014). Effectiveness of health education in community-based malaria prevention and control interventions in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. https://www.academia.edu/download/33117673/Owusu-Addo_Paper.pdf

- Salam, R. A., Das, J. K., Lassi, Z. S., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2014). Effectiveness of community-based interventions for the prevention and control of malaria. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/2049-9957-3-25

- Amoran, O. E. (2013). Impact of health education intervention on malaria prevention practices among nursing mothers in rural communities in Nigeria. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/nmj/article/view/105485

Educational Materials

- Children for Health. Malaria Prevention Education Materials. https://www.childrenforhealth.org/malaria

- JICA. Malaria Prevention and Control Guide. https://www.jica.go.jp/Resource/project/solomon/002/materials/ku57pq00003um0e9-att/Healthy_Village_Facilitator_s_Guide-Malaria.pdf

Staying Updated

Community health nurses should regularly check for updates on malaria prevention and control guidelines, as recommendations may change based on emerging resistance patterns, new interventions, and evolving evidence. Key resources for updates include:

- WHO Global Malaria Programme: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme

- National Malaria Control Program websites

- CDC Malaria Information: https://www.cdc.gov/malaria