Rabies: Community Health Nursing Perspectives

Epidemiology, Prevention & Management

Rabies is a preventable viral zoonotic disease that causes progressive encephalitis, which is almost always fatal once clinical symptoms appear. The word “rabies” comes from the Latin word meaning “to rage,” reflecting the agitated behavior observed in affected individuals.

Despite being one of the oldest recognized infectious diseases, with references dating back to 2300 BCE, rabies remains a significant public health challenge, particularly in developing countries. As community health nurses, understanding rabies is crucial for prevention, early identification, and appropriate management of exposures.

Key Facts About Rabies

- Rabies is caused by neurotropic viruses of the genus Lyssavirus, family Rhabdoviridae

- Transmitted primarily through the saliva of infected animals via bites or scratches

- Dogs are responsible for 99% of human rabies cases worldwide

- Causes approximately 59,000 human deaths annually worldwide

- Almost 100% fatal once clinical symptoms appear

- Preventable through proper post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and pre-exposure vaccination

- WHO has targeted elimination of dog-mediated human rabies by 2030

Historical Significance

In 1885, Louis Pasteur developed the first effective rabies vaccine, using it to save the life of Joseph Meister, a 9-year-old boy who had been bitten by a rabid dog. This breakthrough launched a new era in the management of this previously uniformly fatal disease and represented one of the first successful vaccines against a human disease.

Community Nursing Focus

Community health nurses play a vital role in rabies prevention through education, surveillance, coordinating post-exposure treatment, and advocating for vaccination programs. Their proximity to communities makes them essential in early detection and prevention strategies.

Global Distribution & Burden

Rabies is present on all continents except Antarctica, with over 150 countries and territories affected. The disease disproportionately impacts low and middle-income countries, where access to healthcare resources, including vaccines and immunoglobulins, is limited.

| Region | Estimated Annual Deaths | Primary Reservoir | Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | ~35,000 | Domestic dogs | High |

| Africa | ~21,000 | Domestic dogs | High |

| Latin America | ~200 | Domestic dogs, vampire bats | Moderate |

| North America | ~2 | Wild animals (raccoons, skunks, bats) | Low |

| Europe | ~1 | Wild animals (foxes, raccoon dogs, bats) | Low |

| Australia | 0 | Bats (ABLV) | Very Low |

Risk Factors for Rabies Exposure & Infection

Population Risk Factors

- Children under 15 years (30-50% of cases)

- Rural populations with limited healthcare access

- Occupational exposure (veterinarians, animal handlers)

- Travelers to endemic regions

- People in regions with high stray dog populations

- Communities with low rabies awareness

- Areas with limited or no dog vaccination programs

Animal-Related Risk Factors

- Contact with domestic unvaccinated dogs (highest risk)

- Exposure to wildlife reservoirs (varies by region)

- Unprovoked animal attacks

- Contact with animals displaying abnormal behavior

- Presence of multiple animal bite wounds

- Bites on highly innervated areas (face, hands, fingers)

- Animal bites in rabies-endemic areas

Epidemiological Patterns & Surveillance

Rabies exhibits both urban and sylvatic (wildlife) cycles. In developing countries, the urban cycle predominates with domestic dogs serving as primary reservoirs. In contrast, developed nations with successful dog vaccination programs primarily see the sylvatic cycle involving wildlife reservoirs.

Effective surveillance systems remain a challenge in many endemic regions, leading to significant underreporting. The World Health Organization estimates that the actual number of rabies deaths could be up to 100 times higher than reported figures in some regions, highlighting the need for improved surveillance and reporting mechanisms.

Surveillance Challenges in Rabies Control

- Limited laboratory diagnostic capacity in endemic regions

- Misdiagnosis of rabies cases as other forms of encephalitis

- Poor reporting systems and infrastructure

- Deaths occurring in remote areas without medical attention

- Lack of integration between animal and human health surveillance (One Health approach)

Rabies Virus Characteristics

The rabies virus belongs to the genus Lyssavirus within the family Rhabdoviridae. It has a characteristic bullet-shaped morphology and contains a single-stranded, negative-sense RNA genome. The virus consists of five structural proteins:

- Glycoprotein (G): Forms spikes on the viral surface and is the primary antigen that induces neutralizing antibodies

- Nucleoprotein (N): Encapsidates the viral RNA

- Phosphoprotein (P): Associates with L and N proteins

- Matrix protein (M): Forms the inner layer of the viral envelope

- RNA polymerase (L): Responsible for viral replication

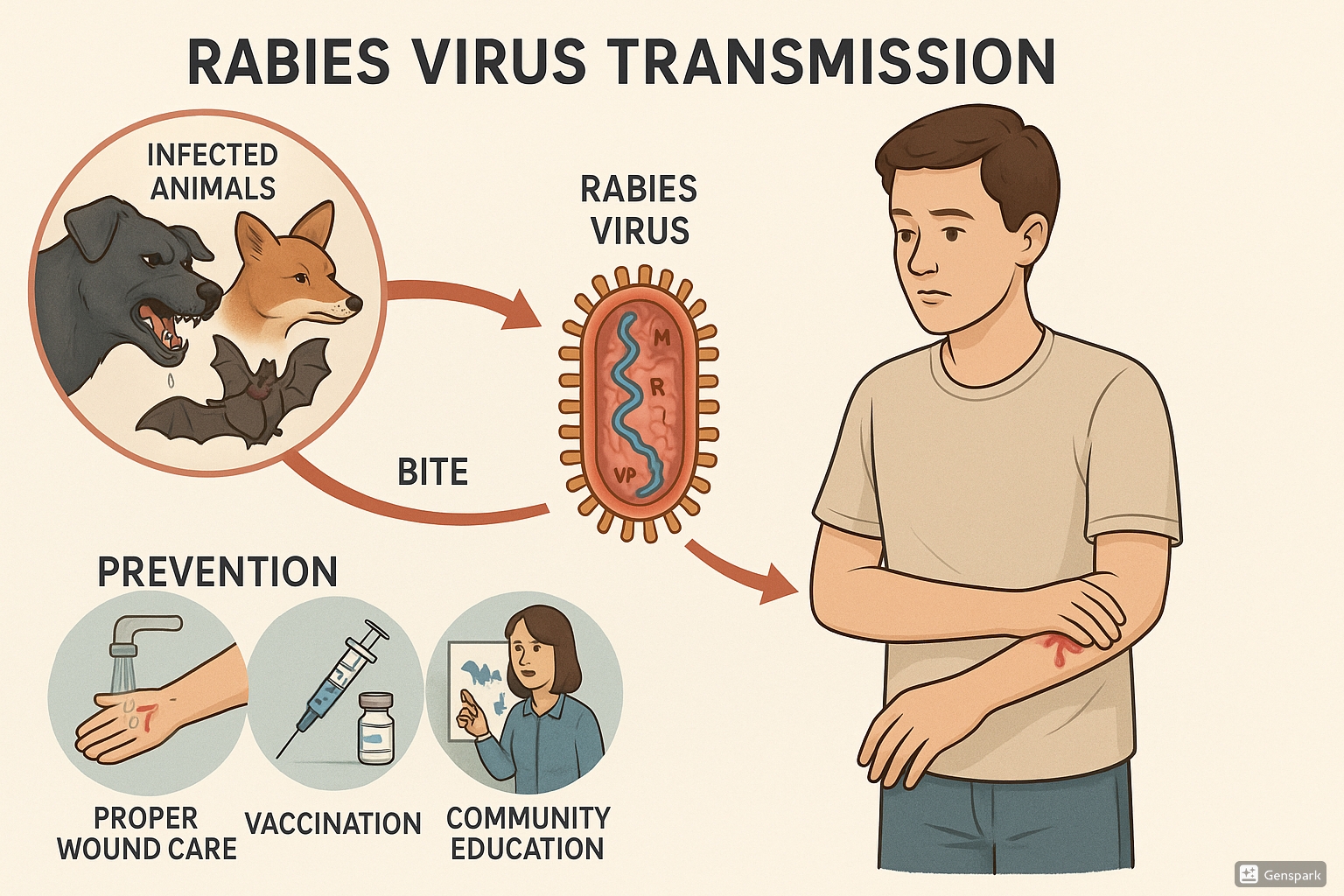

Transmission Cycle

Rabies is primarily transmitted through the bite of an infected animal, as the virus is present in saliva. Less commonly, transmission can occur through scratches, open wounds, or mucous membranes exposed to infectious material. Human-to-human transmission is extremely rare but has been documented through corneal and organ transplantation.

Rabies transmission cycle: From infected animals to humans with key prevention steps

Pathogenesis of Rabies Infection

Phase 1: Viral Entry & Local Replication

After inoculation through a bite or scratch, the rabies virus attaches to muscle cell receptors (nicotinic acetylcholine receptors) at the neuromuscular junction. Initial viral replication occurs in muscle tissue near the entry site.

Phase 2: Peripheral Nerve Migration

The virus enters peripheral nerves and travels to the central nervous system via retrograde axonal transport at a rate of 12-100 mm/day. This explains the variable incubation period based on bite location.

Phase 3: CNS Invasion & Replication

Upon reaching the CNS, the virus replicates rapidly within neurons, causing neuronal dysfunction. From the CNS, the virus spreads via anterograde axonal transport to highly innervated tissues, including salivary glands.

Incubation Period & Determining Factors

The incubation period for rabies is highly variable, typically ranging from 2 weeks to 3 months, with 90% of cases developing within one year. Several factors influence the incubation period:

| Factor | Effect on Incubation Period | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Bite location | Shorter with bites closer to CNS (head, face, neck) | Facial bites may develop symptoms in as little as 5-7 days |

| Wound severity | More severe wounds typically have shorter incubation | Multiple deep bites create greater viral load |

| Viral dose | Higher viral inoculum shortens incubation | Higher viral loads overwhelm local immune responses |

| Host immune status | Immunocompromised may have shorter periods | Impaired immune responses fail to contain initial infection |

| Age of victim | Children often have shorter incubation periods | Related to immune status and bite location frequency |

| Post-exposure prophylaxis | Proper PEP prevents disease development | Even delayed PEP may prolong incubation or prevent disease |

Rabies infection progresses through several distinct clinical phases. Once symptoms appear, the disease is almost invariably fatal, with only a handful of documented survivors worldwide.

Prodromal Phase (2-10 days)

- Fever and malaise

- Headache and general discomfort

- Anxiety, agitation, and irritability

- Paresthesia or pain at the bite site (pathognomonic)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Sore throat

- Increasing sensitivity to light and sound

Encephalitic (Furious) Rabies (2-7 days)

- Hyperactivity, agitation, and bizarre behavior

- Periods of confusion alternating with lucidity

- Hydrophobia (pathognomonic) – painful spasms of pharyngeal muscles when attempting to drink

- Aerophobia – similar reaction to breezes of air

- Hypersalivation and excessive sweating

- Priapism in males

- Tachycardia and fluctuating blood pressure

- Seizures and hallucinations

Paralytic (Dumb) Rabies (2-7 days)

- Gradual, progressive flaccid paralysis

- Usually begins at the bitten limb and ascends symmetrically

- Less dramatic behavioral changes

- Absent or minimal hydrophobia

- Facial weakness progressing to complete paralysis

- Difficulty speaking and swallowing

- Often misdiagnosed as Guillain-Barré syndrome

- More common in bat-transmitted rabies

Coma & Death (0-14 days)

- Progressive deterioration to coma

- Multiple organ failure

- Cardiovascular instability

- Respiratory failure

- Autonomic nervous system dysfunction

- Death typically occurs 7-14 days after symptom onset

- Cause of death usually respiratory arrest

Clinical Pearls for Community Health Nurses

- The presence of hydrophobia is highly suggestive of rabies and warrants immediate action

- Paresthesia or pain at a previous bite site, along with progressive neurological symptoms, should raise suspicion for rabies

- Paralytic rabies is often misdiagnosed as Guillain-Barré syndrome or other flaccid paralysis conditions

- Rabies should be considered in cases of unexplained encephalitis, especially in endemic areas

- Atypical presentations are more common in bat-transmitted rabies

- Always inquire about animal exposure in patients presenting with unexplained neurological symptoms

Rabies prevention strategies are implemented at multiple levels using a One Health approach that recognizes the interconnection between human, animal, and environmental health. Community health nurses play a vital role in many aspects of these prevention strategies.

Primary Prevention Strategies

Animal Vaccination & Control

- Mass dog vaccination campaigns (target: 70% coverage)

- Registration and identification of owned dogs

- Population management of stray dogs

- Wildlife reservoir vaccination through oral baits

- Animal movement control and quarantine

- Enforcement of responsible pet ownership

Human Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)

- Recommended for high-risk populations:

- Laboratory workers handling rabies virus

- Veterinarians and animal control staff

- Cave explorers exposed to bats

- Travelers to high-risk areas with limited access to PEP

- Vaccination schedule: Days 0, 7, and 21 or 28

- Booster doses based on antibody titers or exposure risk

Community-Based Prevention Approaches

Education & Awareness Programs

Community health nurses can implement these educational initiatives:

- School-based education on animal bite prevention

- Community workshops on rabies awareness

- Training on appropriate wound management after animal bites

- Media campaigns on responsible pet ownership

- Targeted education for high-risk groups (children, animal handlers)

- Information dissemination about PEP availability

- World Rabies Day (September 28) awareness activities

Post-Exposure Prevention Protocol

The critical components of rabies post-exposure prophylaxis include wound management, passive immunization with rabies immunoglobulin (RIG), and active immunization with rabies vaccine. Proper and timely administration of PEP is nearly 100% effective in preventing rabies, even after high-risk exposures.

| PEP Component | Timing & Administration | Nursing Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Wound Cleaning |

|

|

| Rabies Immunoglobulin (RIG) |

|

|

| Rabies Vaccine |

|

|

Risk Assessment for PEP Decision-Making

Community health nurses must be able to assess exposure risk to determine appropriate PEP recommendations. The WHO categorizes rabies exposures into three categories:

Category I Exposure

Touching, feeding animals, or licks on intact skin

Recommendation:

No PEP required if history reliable

Category II Exposure

Minor scratches without bleeding or nibbling on uncovered skin

Recommendation:

Immediate wound washing and vaccine only

Category III Exposure

Single or multiple transdermal bites or scratches, contamination of mucous membranes with saliva

Recommendation:

Immediate wound washing, RIG and vaccine

Early diagnosis of rabies is challenging as definitive antemortem testing is limited. Community health nurses must maintain a high index of suspicion based on clinical presentation and exposure history.

Case Definition & Clinical Diagnosis

WHO Clinical Case Definition for Rabies

“A person presenting with an acute neurological syndrome (encephalitis) dominated by forms of hyperactivity (furious rabies) or paralytic syndromes (dumb rabies) progressing towards coma and death, usually by respiratory failure, within 7-10 days after the first symptom if no intensive care is instituted.”

Diagnostic Approaches

Antemortem Diagnosis (In Living Patients)

Limited sensitivity, but important for clinical management:

- Skin biopsy: Detection of rabies antigen in cutaneous nerves at the nape of the neck by immunofluorescence

- Saliva: RT-PCR or virus isolation

- Serum and CSF: Detection of rabies-specific antibodies in unvaccinated individuals

- Corneal impressions: Rarely used, low sensitivity

- Brain imaging: MRI may show hyperintensity in brainstem, hippocampus, hypothalamus, but non-specific

Postmortem Diagnosis (Gold Standard)

Highest sensitivity and specificity:

- Direct Fluorescent Antibody (DFA) Test: Gold standard, detects viral antigens in brain tissue

- Immunohistochemistry: Detection of rabies antigen in fixed tissues

- Cell Culture Isolation: Virus isolation using neuroblastoma cells

- RT-PCR: Detection of viral RNA

- Histological examination: Negri bodies in hippocampus and cerebellum (not always present)

Screening & Monitoring of Animal Bites

Community health nurses play a critical role in screening animal bite cases and coordinating with veterinary services for animal observation and testing.

| Animal Status | Recommended Approach | Nursing Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Domestic dog/cat – healthy and available | 10-day observation of animal (if develops signs, initiate or complete PEP) |

|

| Domestic dog/cat – escaped or unavailable | Assess exposure risk and consider PEP based on local epidemiology |

|

| Wild animals – high-risk species (bat, raccoon, skunk, fox) | Immediate PEP; capture and test animal if possible |

|

| Wild animals – low-risk species (rodents, rabbits) | PEP generally not indicated unless unusual circumstances |

|

| Animal showing clinical signs of rabies | Immediate PEP and testing of animal |

|

Key Considerations for Community Health Nurses

- PEP decisions should never be delayed waiting for animal testing results

- Bats require special consideration – PEP is recommended for all bat exposures unless the bat is tested negative

- Even in previously vaccinated individuals, PEP should be administered after significant exposures (modified schedule)

- Maintain a low threshold for PEP in children who may not report minor bites or scratches

- Always document exposure details for potential epidemiological investigation

- Coordinate with local public health authorities for exposure assessment guidance

Comprehensive Management Protocol

Management of rabies involves two distinct scenarios: post-exposure management to prevent disease development and management of clinically symptomatic rabies. Community health nurses play a crucial role particularly in the former.

Post-Exposure Management

-

Initial Wound Management:

- Immediate thorough washing with soap and water for ≥15 minutes

- Application of virucidal agents (povidone-iodine)

- Tetanus prophylaxis if indicated

- Antibiotics if wound appears infected

-

PEP Administration:

- Risk assessment based on exposure category

- RIG administration for Category III exposures

- Vaccination series administration

- Documentation of all administered products

-

Follow-up Care:

- Wound reassessment

- Ensuring completion of vaccine series

- Animal observation coordination

- Psychological support if needed

Clinical Rabies Management

Once clinical symptoms appear, management is primarily supportive:

-

Admission to ICU:

- Isolation precautions (Standard Precautions)

- Dedicated nursing staff

- Quiet, dimly lit environment

-

Supportive Care:

- Airway management and ventilation support

- Sedation for agitation (benzodiazepines)

- Antiseizure medications

- Hemodynamic support

- Fluid and electrolyte balance

- Prevention of complications

-

Experimental Approaches:

- Milwaukee Protocol (induced coma) – limited success

- Antivirals (ribavirin, interferon) – largely unsuccessful

- Ketamine, amantadine, and therapeutic hypothermia

Referral Protocol & Follow-up

Community health nurses should establish clear referral pathways for rabies exposure cases. The decision to refer depends on the severity of exposure, local capabilities, and available resources.

| Scenario | Referral Level | Community Nursing Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Category I exposure | Primary healthcare facility |

|

| Category II exposure | Facility with rabies vaccine availability |

|

| Category III exposure | Facility with RIG and vaccine |

|

| Severe wounds requiring surgical care | Hospital with surgical capabilities |

|

| Suspected clinical rabies | Tertiary hospital with ICU |

|

Primary Healthcare Management

Essential PEP Components at Primary Healthcare Level

Community health facilities should maintain capabilities for:

1. Wound Management

- Clean water supply

- Soap or detergent

- Povidone-iodine

- Basic wound care supplies

2. Vaccination Capability

- Cold chain maintenance

- Rabies vaccines

- Injection supplies

- Vaccination cards

3. Documentation System

- Bite registers

- PEP administration records

- Referral forms

- Follow-up protocols

Community health nurses are frontline professionals who play a crucial role in rabies prevention, early detection, and management within communities. Their functions span across the spectrum from prevention to clinical management and public health coordination.

Assessment & Surveillance

Community Assessment

- Mapping high-risk populations and areas

- Identifying barriers to rabies prevention

- Assessing community knowledge and practices

- Evaluating local dog population and vaccination status

- Determining PEP accessibility and utilization

- Identifying traditional practices and beliefs related to animal bites

Active Surveillance Activities

- Systematic recording and tracking of animal bite cases

- Contact tracing for exposed individuals

- Monitoring PEP compliance and completion

- Coordinating with veterinary services for animal surveillance

- Reporting suspected rabies cases to health authorities

- Monitoring adverse events following immunization

Case Management & Care Coordination

Initial Response

- Proper wound management

- Risk assessment

- PEP initiation when indicated

- Documentation of exposure

- Tetanus prophylaxis if needed

Follow-up & Continuity

- Ensuring PEP schedule adherence

- Wound care follow-up

- Monitoring for complications

- Coordinating referrals when needed

- Following up on animal testing

Special Populations

- Pediatric bite management

- Pregnancy considerations

- Approach to immunocompromised

- Remote communities’ access

- Cultural considerations

Education & Health Promotion

Educational Interventions

Community health nurses can implement these educational approaches:

Individual Education

- One-on-one counseling for bite victims

- PEP compliance education

- Responsible pet ownership guidance

- First aid for animal bites

Group & Community Education

- School-based programs

- Community workshops

- Media campaigns

- Training for community health workers

- Religious and traditional leader engagement

Educational Topics to Cover

- Animal bite prevention

- Immediate wound care

- When to seek medical attention

- Importance of PEP completion

- Recognition of rabid animals

- Pet vaccination importance

- Dangers of traditional treatments

- Responsible dog ownership

- Available healthcare resources

Intersectoral Collaboration

Effective rabies control requires a One Health approach with collaboration between human health, animal health, and environmental sectors. Community health nurses serve as vital links in this collaborative network.

| Collaborative Partner | Areas of Collaboration | Nursing Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Veterinary Services |

|

|

| Local Government |

|

|

| Educational Institutions |

|

|

| NGOs & International Organizations |

|

|

| Community Leaders & Groups |

|

|

Documentation & Reporting

Essential Documentation Practices

Case Documentation

- Complete bite report forms

- Detailed exposure history

- Animal information

- PEP administration details

- Follow-up appointments

- Adverse reactions

Reporting Procedures

- Immediate reporting of suspected rabies cases

- Regular submission of bite surveillance data

- PEP utilization reports

- Vaccine and RIG stock management

- Adverse events following immunization

- Community education activities

Zero by 30: Global Strategic Plan

In 2015, WHO, OIE, FAO, and the Global Alliance for Rabies Control (GARC) set an ambitious global target: elimination of dog-mediated human rabies deaths by 2030. This initiative, known as “Zero by 30,” provides a comprehensive framework for rabies elimination that community health nurses should understand and support.

Pillar 1: Socio-cultural

Increasing awareness, education, and community engagement to build demand for rabies prevention and create an enabling environment for prevention and control measures.

Nursing Role:

- Community education programs

- Addressing cultural barriers

- Engaging local stakeholders

Pillar 2: Technical

Ensuring effective and accessible post-exposure prophylaxis, reliable diagnostics, and mass dog vaccination as the core interventions for rabies elimination.

Nursing Role:

- PEP administration

- Supporting vaccination campaigns

- Case identification and referral

Pillar 3: Organizational

Developing effective governance, strong policies, adequate resources, and sustainable financing mechanisms for rabies elimination programs.

Nursing Role:

- Advocacy for resources

- Data collection for planning

- Intersectoral collaboration

Success Stories & Lessons Learned

Latin America

Reduced human rabies deaths by over 95% through coordinated mass dog vaccination campaigns, improved surveillance, and PEP access.

Key Success Factors:

- Regional coordination through PAHO

- Sustained political commitment

- Annual vaccination campaigns reaching >80% of dogs

- Integrated surveillance systems

- Training of healthcare personnel

Philippines: Bohol Rabies Project

Eliminated human and dog rabies on Bohol Island through a comprehensive One Health approach.

Key Success Factors:

- Community involvement at all levels

- School-based education program

- Sustainable dog registration system

- Task force with multi-sectoral representation

- Comprehensive dog population management

- Field-level integration of veterinary and human health services

Stepwise Approach to Rabies Elimination

The Stepwise Approach to Rabies Elimination (SARE) provides a framework for countries to assess their rabies situation and incrementally implement control measures. Community health nurses should understand this approach to advocate for appropriate interventions at each stage.

| SARE Stage | Key Activities | Community Nursing Priorities |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 0: Assessment |

|

|

| Stage 1: Initial Response |

|

|

| Stage 2: Scaling Up |

|

|

| Stage 3: Elimination |

|

|

| Stage 4: Maintenance |

|

|

Mnemonics and learning tools can help nursing students remember key concepts related to rabies prevention, diagnosis, and management.

R.A.B.I.E.S.

For remembering key clinical features of rabies

- R – Restlessness and agitation, often early signs

- A – Aerophobia and hydrophobia, pathognomonic signs

- B – Bite history, often with paresthesia at site

- I – Insomnia and progressive deterioration

- E – Encephalitis with altered mental status

- S – Salivation excessive, with difficulty swallowing

B.I.T.E.S.

For animal bite management steps

- B – Bleeding control and wound assessment

- I – Irrigate thoroughly with soap and water for ≥15 minutes

- T – Tetanus prophylaxis if indicated

- E – Evaluate for rabies exposure risk

- S – Seek appropriate PEP based on risk category

P.E.P. STEPS

For post-exposure prophylaxis protocol

- P – Proper wound cleaning immediately

- E – Evaluate exposure risk (Category I, II, or III)

- P – Provide rabies immunoglobulin for Category III

- S – Start vaccination series (Day 0)

- T – Track follow-up doses (Days 3, 7, 14)

- E – Educate on completion importance

- P – Prevent complications through monitoring

- S – Secure documentation of all doses

R.I.S.K.

For high-risk animal exposure assessment

- R – Reservoir species in the area (dogs, wildlife)

- I – Injury characteristics (depth, location, number)

- S – Status of animal (vaccinated, observable, escaped)

- K – Known rabies prevalence in the location

Community Health Nursing Approach to Rabies

The 5 A’s for Community Rabies Control

Awareness

Education about rabies risks, symptoms, and prevention through community outreach, school programs, and media campaigns

Assessment

Risk assessment of communities, identification of high-risk areas, and evaluation of bite incidents

Action

Immediate response to bites, proper PEP administration, and animal control measures

Advocacy

Promotion of dog vaccination, responsible pet ownership, and adequate PEP availability

Alliance

Collaboration with veterinary services, local government, schools, and community leaders

Epidemiology & Prevention

- Rabies causes approximately 59,000 human deaths annually worldwide, with 99% due to dog bites

- The disease is present across all continents except Antarctica, with highest burden in Asia and Africa

- Children under 15 years account for 30-50% of all rabies cases

- Mass dog vaccination (target: 70% coverage) is the most cost-effective prevention strategy

- Pre-exposure prophylaxis is recommended for high-risk populations

- Community education is essential for prevention and early care-seeking

Pathophysiology & Clinical Features

- Rabies virus travels from the wound site to the CNS via peripheral nerves

- Incubation period typically ranges from 2 weeks to 3 months

- Clinical presentation includes prodromal, acute neurologic (furious or paralytic), and coma phases

- Hydrophobia and aerophobia are pathognomonic symptoms

- Once clinical symptoms appear, the disease is almost invariably fatal

Diagnosis & Management

- Clinical diagnosis based on exposure history and neurological symptoms

- Gold standard diagnostic test is Direct Fluorescent Antibody (DFA) test on brain tissue

- Antemortem diagnosis includes RT-PCR on saliva, skin biopsy, and antibody detection

- Post-exposure management includes thorough wound cleaning, RIG infiltration, and vaccination

- PEP is nearly 100% effective if administered properly before symptom onset

- Management of clinical rabies is primarily supportive with poor prognosis

Community Health Nursing Role

- Assessment of community risk factors and surveillance for animal bites

- Wound management and appropriate PEP administration

- Ensuring patient compliance with complete PEP regimen

- Education on rabies prevention, bite avoidance, and responsible pet ownership

- Coordination with veterinary services, local government, and other stakeholders

- Advocacy for sustainable rabies control programs

- Support for global “Zero by 30” elimination goals

- World Health Organization. (2018). WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies: third report. World Health Organization.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2024). Rabies Prevention and Control. https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/prevention/index.html

- Mshelbwala, P. P., Weese, J. S., Sanni-Adeniyi, O. A., Chakma, S., Okeme, S. S., Mamun, A. A., Rupprecht, C. E., & Magalhaes, R. J. S. (2021). Rabies epidemiology, prevention and control in Nigeria: Scoping progress towards elimination. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 15(8), e0009617.

- Sambo, M., Lembo, T., Cleaveland, S., et al. (2014). Knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) about rabies prevention and control: a community survey in Tanzania. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 8(12), e3310.

- WHO, FAO, OIE, & GARC. (2018). Zero by 30: The global strategic plan to end human deaths from dog-mediated rabies by 2030.

- Fenelon, N., Dely, P., Katz, M. A., et al. (2017). Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding rabies risk in community members and healthcare professionals: Pétionville, Haiti, 2013. Epidemiology & Infection, 145(8), 1624-1634.

- World Health Organization. (2024). Laboratory diagnosis of rabies. https://www.who.int/teams/control-of-neglected-tropical-diseases/rabies/diagnosis

- Nurseslabs. (2024). Rabies Study Guide for Nursing Students. https://nurseslabs.com/rabies/

- Lapiz, S. M., Miranda, M. E., Garcia, R. G., et al. (2012). Implementation of an intersectoral program to eliminate human and canine rabies: the Bohol Rabies Prevention and Elimination Project. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 6(12), e1891.

- Rupprecht, C. E., Fooks, A. R., & Abela-Ridder, B. (Eds.). (2018). Laboratory techniques in rabies (5th ed.). World Health Organization.